Can A Sitting US President Go To Jail?

George W. Bush, Barack Obama, Donald Trump, and Joe Biden all share something in common: all four have faced calls for their imprisonment for a plethora of reasons, both during and after their tenures. Now, the idea of locking up a former president is not new, having already surfaced under Richard Nixon thanks to the Watergate scandal. There is nothing illegal or unconstitutional about convicting a former president for crimes committed in office.

The real question is whether a sitting president can be indicted, tried, and convicted without being removed from office through impeachment. This issue received little attention until the 1970s, also in relation to Nixon. The corpus of jurisprudence on this issue has grown, particularly as American presidents become increasingly polarizing figures. Now, plenty of legal scholars and even SCOTUS justices have given opinions on how it could be done, but ultimately, the question is still unresolved because no one has dared to try.

Impeachment vs. Indictment

Today, it is generally accepted that the best way to remove a president is not through criminal indictment but through impeachment, a special process reserved for certain federal officials such as SCOTUS judges, the president, and the vice president. According to the U.S. Senate, impeachment is supposed to be part of the system of checks and balances to remove corrupt executives for "Treason, Bribery, or other high Crimes and Misdemeanors." As the clause suggests crucially, not all crimes are impeachable. The process is simple. First, the House of Representatives must file articles of impeachment listing the charges against the individual. For instance, in the case of President Donald Trump's first impeachment, the charges in the Articles of Impeachment listed abuse of power and obstruction of Congress.

The Articles of Impeachment are approved through a simple House majority, so particularly in politically charged cases, filing impeachment articles is not too difficult. However, in the subsequent Senate trial, a defendant must be convicted by a two-thirds majority. The individual is then removed and barred from office.

The Constitution is vague

Now, a common misconception views impeachment and conviction as synonymous with a criminal indictment and conviction that result in jail time. But impeachment in itself does not result in jail time. According to Georgetown Law Professor Susan Bloch, the question of jail time is far more controversial, namely because the U.S. Constitution — the supreme law of the land — is silent on the issue.

The Constitution clearly lays out impeachment procedures and the associated penalties. Article IV, Section 2 of the U.S. Constitution (via Cornell Legal Information Institute) states that a president or vice president can only be removed through impeachment for four types of criminal acts. Article I, Section 3 (via Cornell LLI) states that the penalty for conviction in a Senate impeachment trial only consists of removal from office and a lifetime ban from holding any other office without any possibility of appeal.

Now, as Bloch notes, this situation leaves plenty of room for interpretation because there is nothing in the Constitution that says a sitting president cannot go to jail, nor does it provide any straightforward procedure for indicting and imprisoning a sitting president accused of crimes without an impeachment. Article I, Section 3 simply says that a president removed from impeachment is not immune to criminal suits and penalties for his crimes while in office (civil suits are another matter). Bloch notes that one interpretation reads that criminal prosecution can only initiate after removal but also cites differing opinions, ranging from ironclad blanket immunity to immunity that Congress can revoke if necessary.

The Founders debated the criminal aspect

The question of prosecuting a president receives some light from the debates of the 1787 Constitutional Convention. There were two competing models of impeachment at the convention. According to the New Jersey Plan (via Yale Law), the executive would be removed through a vote of state governors. The Virginia Plan (via the National Archives), on the other hand, interestingly proposed that all federal officials be tried before the judiciary, but it only sanctioned removal from office without any mention of criminal penalties stemming directly from the impeachment.

In the end, it seems that the Founders intended to insulate the president from criminal charges until after impeachment. The process of impeachment was copied almost exactly from its British counterpart with one crucial difference (per Smithsonian). In Britain, a conviction from impeachment was equivalent to a criminal conviction, and the guilty official could be sentenced to prison. The United States dispensed with this to create the current system, which allows for the prosecution and imprisonment of a former president. This may be in part to protect the president from becoming "a tool of faction," wherein a president would cater to a particular faction or party that had the ability to impeach and remove them. But there were no presidential impeachments that ever raised the question of prison in the early republic.

Comparing to Congress

The issue of a sitting president going to prison never really surfaced until the Nixon years because only one president — Andrew Johnson — had ever been impeached. Thus there was never an opportunity to see how the U.S. government would have reacted to presidential treason or other impeachable offenses with regard to criminal indictments in the republic's early years.

The privileges afforded to other members of the federal government provide some background. Article I, Section 6 of the U.S. Constitution explicitly says that congressmen are immune from arrest. But this is today taken to mean that they are immune from arrest in civil suits when Congress is in session. It does not protect against criminal arrests, as suggested by the phrase listing the crimes of "Treason, Felony and Breach of the Peace." This wording is similar, although not identical to, the wording of the Impeachment Clause's list of offenses. So if congressmen can be arrested, why not the president?

This is the view critics of presidential immunity cite in Reuters. If the Founders intended the president to be immune from any sort of prosecution, they would have made it explicit, just as they defined the charges upon which sitting congressmen could be prosecuted on. There is also another problem: The language of the Impeachment Clause suggests that not all crimes and misdemeanors are impeachable. According to Cornell's Legal Information Institute, the original interpretation of "high crimes and misdemeanors" referred to political offenses against the state. Thus lies the question: Can a sitting president be prosecuted in office for crimes, especially when they do not fall into the impeachable category?

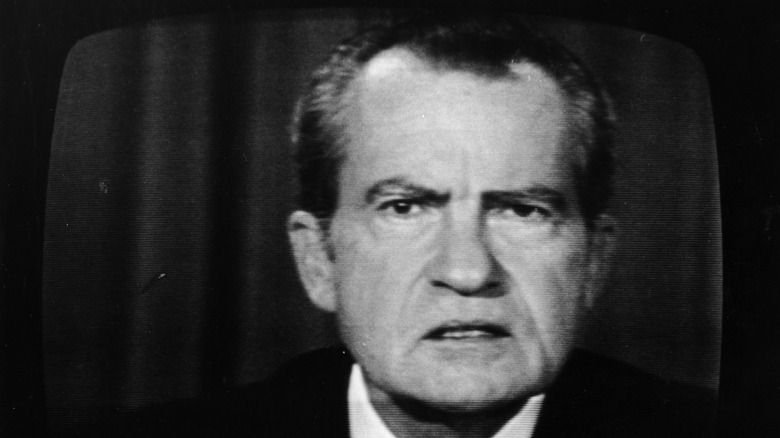

Nixon thought not

So far, it has been established that a president cannot go to prison through impeachment, leaving the possibility of criminal referral. An opportunity to answer the question finally came with the 1972 Watergate scandal when it was concluded that President Richard Nixon had played a role in a break-in at the DNC headquarters at the Watergate Office Building in Washington, D.C. Nixon resigned to avoid impeachment and was never tried or convicted in criminal court, but President Gerald Ford still pardoned him (via Ford Presidential Library) — even for offenses he "may have committed." Ford's action protected Nixon from subsequent prosecution, but Nixon argued that as president, his actions were legal in the context of American national security and presidential responsibilities.

In the famous Frost-Nixon interview of 1977, Nixon argued that a sitting president could not commit crimes in the execution of his duties. Nixon defended his Huston Plan (via NSA Archive), which spied on anti-war activists and political opponents in the name of national security — even if it was illegal. When interviewer David Frost pressed him, Nixon stated clearly that if a U.S. president committed illegal activity in the name of protecting the country, it became legal. Otherwise, he argued, the president would be placed in an "impossible position." So although burglary was illegal — Nixon claimed — he did it for the greater good and could not be prosecuted. This is the basis for not criminally indicting a sitting president, and the Department of Justice of the 1970s took the president's side.

Federal prosecution precedents

As calls to prosecute Richard Nixon grew, the Department of Justice's Office of Legal Counsel issued the first major statement on the question of presidential prosecution with reference to Article I, Section 3 of the Constitution. Now, as noted earlier, Prof. Susan Bloch of Georgetown noted that some scholars agree that impeachment must proceed with criminal proceedings. But the OLC memo argued the opposite.

The OLC argued that Article I, Section 3 intended to prevent the "double jeopardy" defense. Under U.S. law, a person cannot be tried for the same crime twice. Thus, it is reasonable to conclude that a federal official acquitted after an impeachment can avoid criminal indictment for the same upon leaving office. But this would de facto make federal officials above the law. To preempt this, the OLC argued that federal officials could be indicted before impeachment, noting that sitting judges had been criminally prosecuted without impeachment before. So why not the president?

Despite the OLC memo's support for indicting and prosecuting sitting federal officials, it carved out an exception for the president and vice president. The memo argued that it would be impossible to impartially try a president, especially if the charges were politically motivated — an act that would also violate the separation of powers by placing the president under the authority of the judiciary. But most of all, the memo noted that the duties of the president were "so onerous" that they would not be able to discharge them while defending against criminal prosecution, and this would make them vulnerable to 25th Amendment removal — even if they were innocent.

Nixon v. Fitzgerald, 1982

It fell to the Supreme Court to clarify. Richard Nixon was sued by Ernest Fitzgerald, a USAF contractor whom Nixon had fired over his testimony to Congress using the excuse of a reduction in force. Nixon claimed absolute immunity, and the case went to SCOTUS.

In Nixon v. Fitzgerald (via Cornell LLI), SCOTUS ruled that the president had absolute immunity from civil lawsuits over potential constitutional violations committed while executing his responsibilities. The majority opinion, written by Justice Lewis Powell, cited the early Commentaries on the Constitution from 1833, which read, "The president cannot, therefore, be liable to arrest, imprisonment, or detention ... and for this purpose his person must be deemed, in civil cases at least, to possess an official inviolability." SCOTUS, however, rejected the Office of Legal Counsel claim that the separation of powers doctrine insulated the president from the judiciary.

The dissent, led by Justice Byron White, charged that the majority had effectively given the president blanket immunity from criminal prosecution as well. White noted that the Constitution does not bar "Indictment, Trial, Judgment and Punishment, according to Law," suggesting that a president could be indicted and tried legally. The majority dismissed the concern as irrelevant because the Fitzgerald case concerned civil suits. But Powell never claimed White was incorrect, suggesting that a sitting president was not protected from criminal liability — at least in theory. But as the OLC memo noted, there is a difference between theory and practice, given the practical hurdles to prosecuting a sitting president.

The Rotunda Memo: Yes to indictment, no to imprisonment

The Fitzgerald ruling ignited a vigorous debate over how to prosecute a sitting president that hit the headlines in 1998 during the Clinton impeachment. The Bill Clinton Articles of Impeachment included witness tampering, obstruction of justice, and lying to Congress — all criminal charges. Congress had yet not initiated impeachment, so Special Counsel Kenneth Starr contacted University of Illinois Professor Ronald Rotunda for advice on indictment.

The famous Rotunda memo argued for Bill Clinton's indictment for actions unrelated to his duties, such as lying to Congress. A criminal indictment did not conflict with impeachment, which was a separate procedure to remove an official from office. Rotunda's argument rested upon Clinton v. Jones, which decreed that the president was not above the law and could be civilly sued for violations pre-dating his tenure. Thus, a special counsel in conjunction with a federal grand jury, in Rotunda's opinion, could indict a sitting president — but not jail them.

The Rotunda memo, unlike the Office of Legal Counsel memo, created a scheme to ensure the least amount of disruption if a president were indicted and prosecuted. Rotunda suggested that criminal indictment go ahead if Congress opted to impeach and be delayed if it did not. If a president was convicted in criminal court while in office, Rotunda suggested leaving them free until they were out of office in the case that Congress voted to acquit them in a separate impeachment trial, since the bar for impeachment is different from that of a criminal trial. This scheme ensured that a president could continue to execute their duties during any proceedings.

Claiming immunity

In response to the Rotunda memo and its advice, the Clinton administration responded with its own memo claiming absolute immunity from prosecution while the president was still in office. The argument based itself primarily upon a brief from Richard Nixon's Solicitor General Robert Bork. In the memo, Bork argued that the president was immune from indictment. While federal officials such as judges could be criminally indicted and, as a result, hampered from performing their duties, the indictment of a single judge did not stop the judicial branch of government from functioning. But indicting the head of state was a very different matter, as the Clinton Department of Justice argued.

The Clinton DOJ turned back to the president's responsibilities and argued that because the president occupied such a crucial function in lawmaking, national defense, and foreign relations, it would be impossible to properly execute these duties in the face of the intense public scrutiny that would come with a criminal indictment. A criminal (as opposed to a civil) indictment was a public matter rather than an individual complaint over civil rights violations. In the world of mass media and the "delicacy of the political relationships which surround the Presidency both foreign and domestic," any indictment would turn the presidency into a media circus while damaging the credibility of both the presidency and the United States abroad.

Laurence Tribe and exceptional circumstances

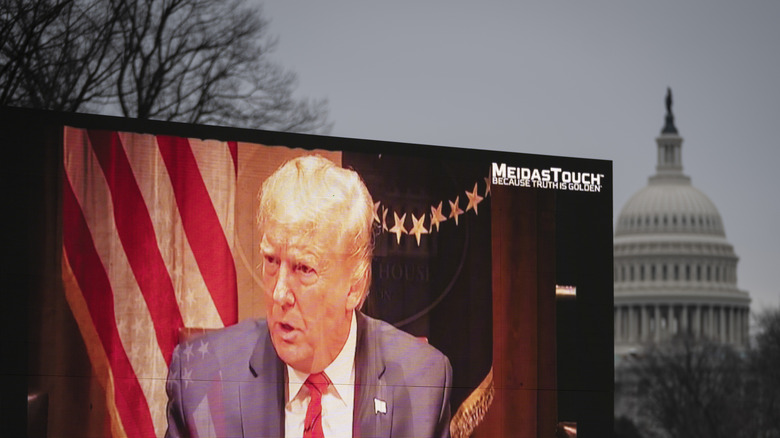

In 2018, calls for President Donald Trump's impeachment over alleged collusion with the Russian government to rig the 2016 election also led to calls for the president's indictment under Special Counsel Robert Mueller. Now, among those weighing in was Harvard professor Laurence Tribe, who on Lawfare argued that although it was generally accepted that a sitting president could and should not be indicted, the Constitution permitted it in exceptional circumstances — presumably in reference to Trump's alleged election tampering.

If a president shot someone in the middle of the street in broad daylight, no one would argue against it being a criminal offense. Using this example, Prof. Tribe argued that it would be asinine to wait for congressional impeachment proceedings before indicting, trying, and convicting the president for murder in criminal court. Secondly, Tribe touched on another aspect of law that he argued is in support of the necessity of indicting a president — the statute of limitations.

Tribe argues that if no one is above the law, the Constitution should allow a president to be indicted while in office, especially since prosecution becomes less likely with the passage of time. Now, per the Cornell Legal Information Institute, the federal statute of limitations for non-capital offenses is five years. Thus, as Tribe notes, a two-term president can easily escape indictment for anything committed within his first term simply by serving a second and running out the statute of limitations — an idea that conflicts with the supremacy of law.

What about Trump?

So how does all of this relate to Donald Trump? The issues surrounding Special Counsel Robert Mueller's investigation and the subsequent first impeachment show the complications with indicting a sitting president but also highlight the distinction between indictment and impeachment.

According to Mueller himself (via NBC News), Trump was not indicted because the previously mentioned Office of Legal Counsel memo was official Department of Justice policy. However, Mueller also did not find sufficient evidence to charge the president, so it is unclear if he eschewed indictment because of the memo or lack of evidence (per the American Bar Association). Regardless, it is unlikely that Trump can face trial over Russian collusion as a private citizen. The alleged crime would have occurred in 2016 or prior. As noted by the Cornell Legal Information Institute, the purported crimes, unless charged as capital treason, are subject to the five-year statute of limitations in light of the failure of the No President is above the Law Act, which would have suspended the statute of limitations for presidential crimes.

Unlike Bill Clinton's impeachment, the Mueller investigation and Trump's first impeachment were not related. So while Clinton was impeached on the same charges that Starr wanted to indict him on, Trump, per his Articles of Impeachment, faced trial over Ukraine-related charges — not the collusion investigation. Now, Trump could theoretically be charged in court with obstruction of Congress, which carries a five-year prison sentence (via the Congressional Research Service). But that seems unlikely given the statute of limitations and his impeachment acquittal.

Uncharted waters

Now, what about Donald Trump's second impeachment? This trial is interesting because, according to the Articles of Impeachment, Trump was charged with incitement to insurrection over the January 6, 2021 events at the U.S. Capitol — after he had already left office. A handful of legal experts interviewed on NPR, including Yale's Akhil Amar, argued that the trial was constitutional — even if merely symbolic. Amar could point to the impeachment of Ulysses Grant's Secretary of War William Belknap, who was impeached despite resigning to avoid just that.

However, both Columbia's Philipp Bobbit and former Special Counsel Ken Starr (via Fox News) argued that the trial was unconstitutional. Since the impeachment clause states that penalties for an impeachment conviction cannot extend beyond removal from office and a ban on future federal employment, it served little purpose if the hope was to imprison him. Because the impeachment occurred after Trump's tenure, Starr called the trial a "dangerous precedent," noting that it left former federal officials — including Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton — open to such impeachment. But if any of the aforementioned officials were convicted in such a trial, what would the penalty be?

As WUSA9 noted, the Senate cannot impose any penalties beyond removal, so despite all the hype around presidential impeachments, only a criminal trial can send a president to prison. And given the ramifications of putting a sitting president in front of a jury, it is very likely that if one is ever indicted, they will be a former one.