The Real-Life Murders That Inspired Agatha Christie's Mysteries

As Book Riot notes, few mystery writers have had an impact on pop culture as astonishing as Agatha Christie. Whether you think of her as the "Queen of Crime" or the "Duchess of Death," she was a master weaver of tales filled with so many twists and turns that only the most mentally agile characters could unravel them. Of course, these fictional humans were also known for their general likeability, strange eccentricities, and fascination with solving murders. Whether we're talking about the mustachioed Belgian detective Hercule Poirot or the elderly spinster and amateur sleuth Jane Marple.

Christie remains one of the most famous bestselling authors of all time, having penned 14 short story collections and 66 full-length mysteries, which have been translated into more than 100 different languages. Her books have also been the inspiration for countless movies and television shows. She inspired one of the longest-running theater productions in history. And as for the hundreds of authors she's influenced in one way or another — well, that's hard to quantify.

But what many people may not realize is that Christie often looked to true crime for inspiration (via "Agatha Christie's True Crime Inspirations: Stranger Than Fiction"). From the serial murders of Jack the Ripper to the kidnapping of Charles Lindbergh's son, Christie used real-life events to spark some of her greatest works. Here's what you need to know about the real-life murders (and other crimes) that inspired Agatha Christie, one of the world's most celebrated mystery writers.

Murder on the Orient Express

In 2017, a star-studded cast featuring Johnny Depp, Kenneth Branagh, Penelope Cruz, Judi Dench, and Michelle Pfeiffer brought Agatha Christie's novel "Murder on the Orient Express" to life on the silver screen (via IMDb). According to "Agatha Christie's True Crime Inspirations: Stranger Than Fiction," the author sought inspiration for the storyline by focusing on THE "trial of the 20th century": the 1932 kidnapping and murder of Charles Lindbergh's infant son.

As The Home of Agatha Christie details, the baby disappeared from his crib in the middle of the night, and his body was found a few days later. One of the members of Lindbergh's household staff, Violet Sharp, came under suspicion and heavy public scrutiny, resulting in her taking her own life. After her death, police decided Sharp was innocent. Eventually, they focused on a German American immigrant named Bruno Hauptmann who maintained his innocence right up until his execution.

In "Murder on the Orient Express," Christie revamped the case through the Armstrong kidnapping subplot. In the novel, a little girl named Daisy Armstrong is the murder victim, and the shock of her kidnapping and death kills her mother, pregnant with Armstrong's little sister. This is followed by Daisy's father taking his own life. Adding these extra deaths heightened the tragedy of the story while providing enough of a twist to ensure it didn't appear identical to the original case.

The ABC Murders

In "The A.B.C. Murders," Agatha Christie put Hercule Poirot hot on the trail of a serial killer who appeared to kill simply for the pleasure of it (via "Agatha Christie's True Crime Inspirations: Stranger Than Fiction"). Murders occur across the British Isles with the murderer sending letters detailing where he'll strike next.

These events are organized alphabetically by the first letter of each city and each victim's first and last name. If this all sounds a bit familiar, that's because Christie found inspiration for this story in one of the most horrific unsolved true crime mysteries in history, the sick tale of Jack the Ripper, per Crime Reads. The motiveless nature of each crime in "The A.B.C. Murders" evokes Jack the Ripper's wave of terror in Whitechapel in 1888, which featured cheeky correspondence with local law enforcement.

Although the murders occurred in an area of London known for violence and lawlessness, Jack the Ripper's crimes proved so vicious and sickening that they garnered national and international attention. The serial killer's crime wave took place in 1888 and resulted in the deaths of multiple prostitutes whose bodies were gruesomely mutilated. Following each death, the suspect bragged by sending letters signed "Jack the Ripper," which Christie mirrored through "The A.B.C. Murders" antagonist's penchant for self-publicizing, according to ABC News.

Ordeal by Innocence

Few true crime stories shocked the nation more than Lizzie Borden's ax-wielding murder of her father and stepmother in 1892, per The New York Times. The sensationalism of the crime and its infamy made it perfect fodder for an Agatha Christie mystery. According to Mike Holgate's "Agatha Christie's True Crime Inspirations: Stranger Than Fiction," this came in the form of "Ordeal by Innocence," where Christie explores the murder of Rachel Agyll by her housekeeper Kirsten Lindstrom.

As with the Borden case, a member of the household proves guilty, via Radio Times. What's more, it's revealed that Lindstrom acted on behalf of Jack Agyll, Rachel Agyll's adopted son. This echoes Lizzie Borden's alleged murder of her stepmother and father. Christie even explicitly mentions the Lizzie Borden case two times in the book.

But "Ordeal by Innocence" wouldn't be the only Agatha Christie book to delve into the Borden murders. Christie definitely betrayed an ongoing fascination with the true crime sensation. We find mentions of it in 1939's "And Then There Were None" and 1976's "Sleeping Murder." In 1953's "After the Funeral," the Queen of Crime even included the gruesome nursery rhyme about the murders (via The Irish Times): "Lizzie Borden took an axe and gave her mother 40 whacks. When she saw what she had done, she gave her father 41."

The Secret Adversary

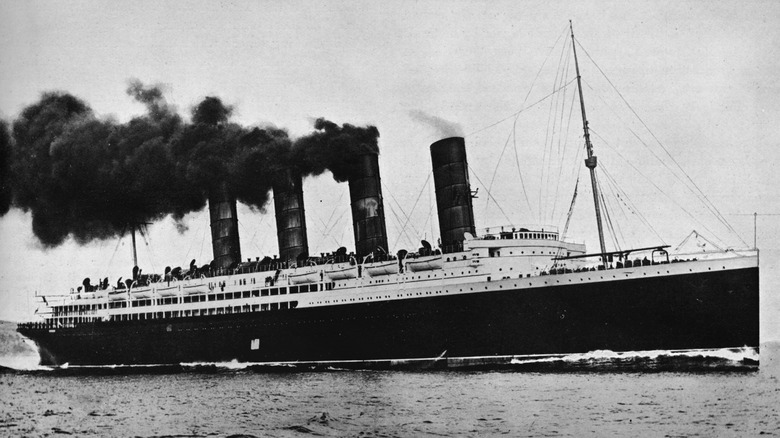

When the RMS Lusitania sank in 1915, it represented a point of no return between the United States and Germany, according to the Ports, Past and Present Project. The notorious war crime involved the double-torpedoing of the British luxury liner the Lusitania by a U-boat (via History). The attack resulted in the deaths of 1,195 passengers, including 128 Americans.

As with true crime tales from the past and present, Agatha Christie ripped the story from newspaper headlines, making the Lusitania a setting of her mystery novel "The Secret Adversary." The story opens aboard the ship as passengers scramble for lifeboats: "The women and children were being lined up awaiting their turn. Some still clung desperately to husbands and fathers; others clutched their children closely to their breasts." It's into this chaotic scene that a mysterious American male entrusts critical government documents with Jane Finn, a self-proclaimed patriot.

After leaving the Lusitania behind to the ravages of time and a watery grave, much of Christie's novel takes place in London. There, we follow two amateur sleuths, Tuppence and Tommy, as they struggle to track down the obscure woman and learn more about the papers in her possession. To solve the case, the sinking of the Lusitania becomes a recurrent theme as details get revisited to find the missing girl. This underscores the current event spark that fueled the author's twisting plot.

The Mysterious Affair at Styles

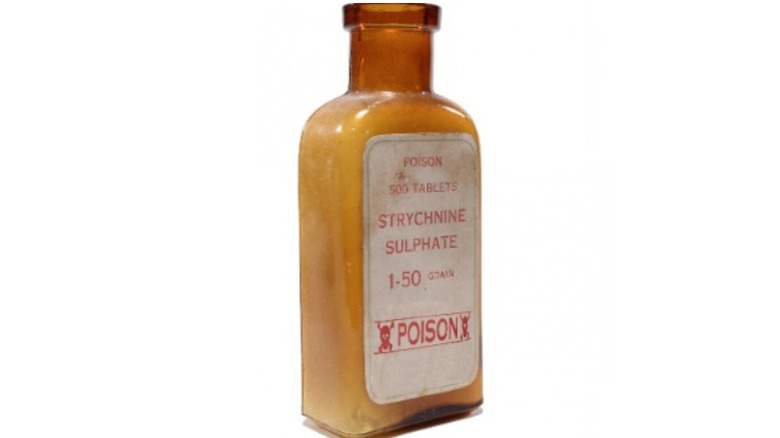

Agatha Christie's debut novel features murder by strychnine, a plot influenced by her time as a nurse at Torquay War Hospital during World War I, per The Conversation. But the plot may also derive inspiration from the well-publicized murder of an English spiritualist in 1911 at India's Savoy Hotel.

The hotel opened in 1902 in Mussoorie, a hill station established by the British in the 1820s. Cecil D. Lincoln, a barrister from Lucknow, Ireland, constructed it, sparing little expense. The Savoy featured lancet windows, spires, and other facets of Gothic architecture. A veritable army of movers transported grand pianos, billiard tables, crates of Champagne, and Edwardian furnishings up mountainous roads to the opulent location. So, when Frances Garnett-Orme, a 49-year-old spinster, and her friend Eva Mountstephen arrived, murder was the last thing on anyone's mind.

But then Garnett-Orme turned up dead, and medical examination showed she'd been poisoned with strychnine. Mountstephen was brought up on charges of murder but acquitted due to a lack of evidence. Perhaps most shocking, the physician who performed the autopsy died from strychnine poisoning a few months after Mountstephen's trial. Details from this sensational case would make their way into Christie's "The Mysterious Affair," including the strychnine poisoning. But she relocated the action to Styles Court in Essex, England.

The Labors of Hercules

"The Mysterious Affair at Styles" wouldn't be the last time poison factored into an Agatha Christie murder mystery, according to "True Crime Parallels to the Mysteries of Agatha Christie." In fact, chemical homicide played a prominent role in many of Christie's mysteries, along with details borrowed from true crime. In the short story "The Lernean Hydra," part of Christie's "The Labors of Hercules" collection, the author revisited the notorious case of Harold Greenwood.

Greenwood stood trial for murdering his wife Mabel, a wealthy heiress, with arsenic (via WalesOnline). Some historians claim Greenwood would've never gone to trial if it weren't for the tremendous public outcry in the wake of her death. What's more, an autopsy of Mrs. Greenwood confirmed her cause of death as arsenic poisoning. The crime took place in 1920, allegedly motivated by money and Greenwood's desire to marry a much younger woman.

Christie's piece explores the murder of Mrs. Oldfield and the presumed guilt of her husband, Dr. Oldfield. Like the Greenwood story, gossip and public outrage play central themes as Hercule Poirot dives into the circuitous case. In keeping with the original Greenwood case, Dr. Oldfield is also a noted adulterer. And Mrs. Oldfield has a personal medical assistant just like Mrs. Greenwood. Topping it all off are rumors perpetuated by disgruntled ladies and nosy neighbors that force local law enforcement to bring Dr. Oldfield to trial.

The Affair at the Victory Ball

For her short story "The Affair at the Victory Ball," showcased in the collection "The Mysterious Mr. Quin," Agatha Christie drew on the sensational real-life death of music hall star Billie Carleton, who overdosed on cocaine (via Flashbak). The original case included just about everything you could want from a high-profile murder mystery, including a makeshift opium den, a young starlet cut down in her prime, and a jewel-encrusted box of cocaine.

There were also accusations against Reginald de Veulle, Carleton's fashion designer, for supplying her with the drugs that contributed to her overdose. But all the evidence showed for sure was that he'd made the black georgette (and largely see-through) costume she wore to the Victory Ball. She attended this ball on the eve of her death.

Christie's short story takes a similar tack, featuring the fictional up-and-coming celeb Coco Courtenay, per Christie's Mysteries. The actor attends the Victory Ball with Lord Cronshaw, her rumored fiance. A quarter century older than Courtenay, Cronshaw disapproves of her drug use, and they part ways poorly that evening.

Courtenay leaves the ball in tears with her acting colleague, Chris Davidson, heading home to her Chelsea flat. The next morning, her lifeless body turns up with a box of cocaine next to it. Soon, fingers point toward Davidson as her white powder supplier, reflecting the real-life controversy that encircled de Veulle after Carleton's death.

The Murder on the Links

Agatha Christie's era boasted plenty of true crime material perfect for reworking in mystery novel plots. For example, there's the real-life story of the so-called "Red Widow," Madame Marguerite Steinheil, accused of killing her husband and mother and staging her own kidnapping in 1908, per the Vancouver Sun. She stood trial the next year, an event that captured the national imagination and inspired plenty of wannabe sleuths.

As reported by the Vancouver Sun, "All the amateur detectives of Paris are advancing fantastic theories to account for the strangling to death of Adolph Steinheil and Madame Japy, his mother-in-law, in Steinheil's studio." And there was plenty of intrigue to heighten their curiosity. For starters, the "Red Widow" was found bound and gagged in the same house where her husband and mother died, but some said the bonds were suspiciously loose. Despite the rumors and crowd of potential detectives, Marguerite Steinheil was acquitted.

Agatha Christie revisits this shocking true crime episode in 1923's "The Murder on the Links" (via Goodreads), another Hercule Poirot novel. In it, the Belgian detective relies on the patterns found in human nature to solve the case. Along the way, he faces competition from other detectives (evoking the army of investigators that dove into the Steinheil case), and there's an engineered kidnapping that morphs into a staged death, echoing the "Red Widow's" suspicious, though bound, presence in the house where the murders occurred.

Three Blind Mice

In 1945, a tragic case of child abuse and neglect rocked the British Isles, according to Community Care. It involved the death of Dennis O'Neill, a foster child whose fate was decided by the Newport Borough Council. The Council placed him and his brother, Terence O'Neill, with Reginald and Esther Gough. Seven months later, Dennis O'Neill lay dead at "the [Gough's] very bare, comfortless and isolated" farmhouse.

Before giving custody of the O'Neills to the Goughs, the Newport Borough Council failed to properly investigate the couple. They also dropped the ball on follow-up visits and a recommendation on December 20, 1944, to immediately remove the boys from the Gough home. During the Goughs' courtroom trials, horrific details of the boys' lives emerged, including the near-starvation diet they faced and brutal beatings. Just shy of his 13th birthday, Dennis O'Neill died of cardiac arrest on January 9, 1945. His body showed signs of severe beatings to the chest, back, and legs and exposure to the elements.

According to biographer Janet Morgan, the tragic story of Dennis O'Neill had a profound impact on Agatha Christie, who examined the events in the radio play "Three Blind Mice." In Christie's version, murder stalks a group of people trapped together in a country house in the dead of winter. A couple of years after the debut of "Three Blind Mice," it reappeared as "The Mousetrap," the longest-running play to hit London's West End (via The Home of Agatha Christie).

The Mirror Crack'd from Side to Side

The real-life tragedy of Gene Tierney provided the basis for the plot of "The Mirror Crack'd from Side to Side," per The Home of Agatha Christie. As reported by The Vintage News, Tierney was married to Oleg Cassini and enjoyed a Hollywood lifestyle. A woman of extraordinary looks, her chiseled cheekbones and emerald-colored eyes lit up the silver screen in movies like "Leave Her to Heaven," "Laura," and "The Razor's Edge."

But Tierney's life dissolved into tragedy after a chance meeting with one of her fans, a female marine at the Hollywood Canteen. It represented Tierney's only appearance with the USO during World War II. Sadly, the fan escaped from a measles quarantine to see Tierney and likely transmitted rubella to the star. At the time, Tierney was pregnant with her daughter, Daria. Because of the illness, Daria was born prematurely with many disabling health problems, including mental disability, deafness, and partial blindness. She weighed little more than 3 pounds.

Years later, Tierney learned that she'd contracted the measles from the female fan after a chance meeting between the two. During the meeting, the fan confided in Tierney about escaping quarantine to see her despite being sick. The news devastated Tierney, but unlike her Agatha Christie counterpart in "The Mirror Crack'd from Side to Side," Tierney didn't descend into a poisonous rage like Christie's character Marina Gregg.

Mrs. McGinty's Dead

"Mrs. McGinty's Dead" sprang from the fertile ground of a true crime love triangle and murder (via "True Crime Parallels to the Mysteries of Agatha Christie"). According to The History Press, the case involved Dr. Hawley Harvey Crippen, who was found guilty of murdering his wife Belle Elmore (aka Cora Turner) and dismembering her body. After the murder, he buried her in the cellar.

When friends inquired about Elmore's whereabouts, Crippen's story changed. To some, she was in America, to others ill or even dead. In another twist, the doctor told police Turner had run off with a male lover. Suspicions increased when the doctor moved his typist-turned-lover, Ethel Le Neve, into the house, and she started wearing Elmore's jewelry. Soon, the doctor panicked, shaving his mustache and fleeing with Le Neve whom he attempted to pass off as his son. But the duo proved too affectionate to be father and son and soon wound up in police custody. Police uncovered Elmore's flesh in the cellar, and Dr. Crippen hung for his crimes. But doubts lingered about Le Neve's complicity.

In "Mrs. McGinty's Dead," Agatha Christie includes many allusions to the Crippen case. There's Dr. Rendell, for example, suspected of killing his first wife many years earlier. But the most obvious character drawn from the Crippen whole cloth is Eva Kane. Once upon a time, Kane was involved in a love triangle that had motivated a husband to kill his wife and bury her — you guessed it! — in the cellar (via From Print to Screen).