Japanese Americans Who Resisted Internment During WWII

The First and Second World Wars had immeasurable consequences when it came to how militaries waged war, the geographic locations that could be impacted by conflict, and how soldiers and civilians got treated on the battlefield and in internment camps. Of course, when most people hear the term "internment camp," their mind immediately races to WWII and the German camps where political prisoners, Jews, Roma, and the handicapped faced imprisonment and selective extermination. But mass incarceration of populations has a much longer history, according to the International Encyclopedia of the First World War.

From 1914 to 1919, more than 30,000 enemy aliens faced imprisonment in and deportation from the British Isles, their only crime being their country of origin. And Europe saw the imprisonment of 400,000 enemy aliens with everyone getting into the mix, including neutral nations like the Netherlands. Forcing ethnicities into concentrated masses during wartime has deep historical roots, exemplified by the reconcentrado system employed in Cuba by the Spanish during the 1890s and the reservation system spearheaded by the United States through the 1851 Indian Appropriations Act (via History).

Conditions varied wildly at these locations, from the relatively humane treatment of German-born Brits at Knockaloe Farms to the starvation conditions on Montana's Blackfoot reservation during the winter of 1884, per Smithsonian Magazine. Sadly, Japanese Americans experienced internment during WWII, but a brave few resisted these camps, which were just one of the messed up things that happened during the war. Keep reading to learn more about those who fought against forced relocation and incarceration imposed by Executive Order 9066.

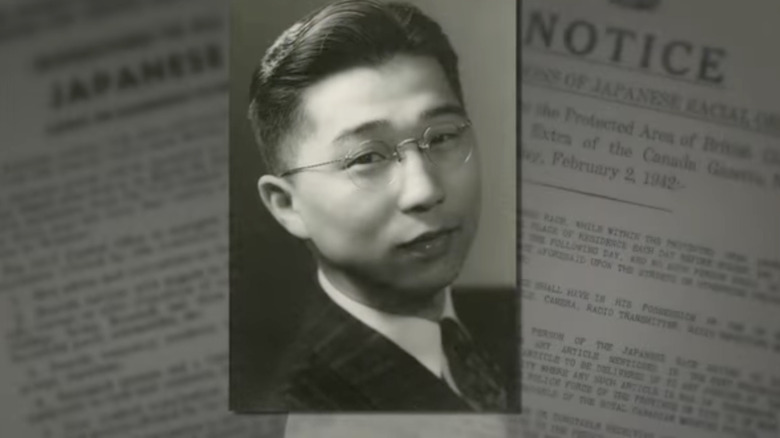

Gordon Hirabayashi

World War II is marked by many important dates, including one that President Franklin Delano Roosevelt declared would "forever live in infamy," December 7, 1941, according to the National Archives. In the early afternoon, the Empire of Japan surprise attacked the United States with air and naval forces. More than two thousand American service members died, including 68 civilians, per the National WWII Museum (via Census). Nineteen American naval ships, including eight battleships, were damaged or destroyed.

On February 19, 1942, FDR issued Executive Order 9066, as reported by the National Archives. This order permitted the removal of enemy aliens and national security threats to concentration camps. Over the next six months, more than 100,000 Japanese Americans (including women and children) faced evacuation to isolated camps. Among these numbers was Gordon Hirabayashi, a senior at the University of Washington, per the United States Forest Service.

Upon hearing about the racially motivated restrictions imposed on Japanese Americans, Hirabayashi knew he had to oppose these unconstitutional measures (via the Densho Encyclopedia). He refused to comply with the curfew placed on Japanese Americans and wouldn't report for relocation. Instead, he turned himself into the FBI, hoping to launch a test legal case against the government. The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) soon represented him. Hirabayashi's case went to the Supreme Court where the justices ruled against him on June 21, 1943. However, Hirabayashi wouldn't be the last person to challenge incarceration.

Minoru Yasui

Minoru Yasui was born in Hood River, Oregon, to Japanese immigrants, and he graduated from the University of Oregon School of Law (via the Oregon Encyclopedia). He passed the Bar in Oregon and served as a second lieutenant in the US Army Infantry Reserve. After relocating to Chicago, he worked in the Japanese Consulate until Pearl Harbor. Following the attack, Yasui immediately resigned, returning to Oregon to prepare for active duty, per the Densho Encyclopedia.

But instead of military service, he faced restrictive curfews and relocation to a concentration camp. He opposed these measures, placing his personal liberty and professional career on the line. The government justified these actions with racist logic: "Japanese racial characteristics naturally promoted [Japanese Americans] to be loyal to Japan and to betray the United States, regardless of their citizenship." Nevertheless, Yasui recognized this unconstitutional discrimination for what it was, and he knew a legal challenge must follow. He purposely violated curfew, strolling the streets of Portland on March 28, 1942. A criminal offense on the federal level, Yasui paid dearly for his actions.

He received a sentence of one year in prison and a $5,000 fine (the equivalent of $89,661.35 in 2022). Appealing the case, Yasui faced nine months in solitary confinement. By 1943, his case reached the Supreme Court, where the justices ruled he could not lose his American citizenship, but they argued the rights associated with American citizenship could be suspended during wartime.

Fred Korematsu

While walking the streets of San Leandro, California with his Italian American girlfriend, Ida Boitano, in 1942, the police arrested Fred Korematsu on suspicion of being Japanese (via Smithsonian Magazine). Initially, the 23-year-old Oakland-born welder claimed to be Clyde Sarah, an American of Hawaiian and Spanish descent, but under the scrutiny of law enforcement questioning, this narrative unraveled. Eventually, he admitted to being a Japanese American, and he explained that he had remained in Oakland to earn money so that he and his girlfriend could move to the Midwest.

After police questioned him about facial scars, he admitted to having plastic surgery to fix a broken nose, and his surgeon and Boitano confirmed this, emphasizing its minor nature. The media ran with the story, creating hysteria about Japanese Americans undergoing surgery to blend in. Between the fog of war and espionage fears, heightened irrationality led to ugly front page racism as California newspapers struggled to justify the harsh treatment of fellow Americans.

Despite the fact Korematsu had never been to Japan, spoke the language poorly, and had even registered for the draft, he faced imprisonment followed by incarceration in an internment camp. Sadly, government officials pressured Boitano to cut ties with him, and he never saw her again. Boitano feared a similar fate since Italy sided with Germany at the start of WWII. In 1944, the Supreme Court upheld his incarceration as militarily necessary, birthing one of the worst precedents in American history (via the Korematsu Institute).

Mitsuye Endo

Born in Sacramento, California, Mitsuye Endo was the daughter of Japanese American immigrants. Even though things weren't easy for women during the war, things were even worse for women facing internment. She would embark on one of the most successful legal resistances against Japanese American internment, as reported by the Densho Encyclopedia. Her case proved historic, eventually leading to the closure of concentration camps and the return of Japanese Americans to the West Coast in 1945, per The Washington Post.

Endo's struggle began after she, along with 300 to 500 Japanese American employees, were summarily dismissed by the California Department of Employment following Pearl Harbor. Of the hundreds of individuals who lost their jobs, Endo was one of 63 who publicly decried the injustice. The 63 turned to the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL) and lawyer James C. Purcell for help.

Legal remedies take time, and Endo ended up in a concentration camp at Tule Lake. Then Purcell contacted her for participation in a test case. He chose her for three reasons. First, she'd never been to Japan. Second, her brother served in the military, and, third, she was a Methodist. Although the two never met in person, Purcell got her to agree, albeit reluctantly, to participate in the legal action. Years later, in an interview with John Tateishi, she explained, "I agreed to do it at that moment, because they said it's for the good of everybody, and so I said, well if that's it, I'll go ahead and do it."

Mary Asaba Ventura

The case of Mary Asaba Ventura highlighted the inconsistency of America's policies towards Japanese Americans, as reported by Greg Robinson's "The Unsung Great: Stories of Extraordinary Japanese Americans." Ventura was a Japanese American born in the United States who married Mamerto Ventura, a Philippine labor activist and citizen (via Peter Irons' "Justice at War"). Yet, she couldn't go out past curfew, even when accompanied by her husband. And unlike her husband, she also faced other restrictions and incarceration solely because of her ethnicity.

Recognizing the utter hypocrisy of the situation, she filed a habeas corpus petition in Seattle, Washington, to challenge the restrictions and curfew imposed upon her and other Japanese Americans. But Lloyd D. Black, a Washington judge, denied her petition, arguing that the restrictions did not represent imprisonment. Black didn't end there. He also concluded that the laws impacting the Japanese American community were constitutional. To add insult to injury, he suggested that if Ventura wished to show her loyalty to the nation, she'd comply with them.

Fearing indefinite removal from her family, Ventura next went to the Western Defense Command, petitioning for the right to remain with her husband. This second attempt at resistance failed, too. Sadly, Ventura got relocated to Minidoka where she faced internment without her family.

Theresa Takayoshi

Like the story of Mary Asaba Ventura, Theresa Takayoshi's experience during World War II illustrated the confusion surrounding Executive Order 9066. The policy represented both a muddied and muddled attempt at addressing the enemy alien threat, per Greg Robinson's "The Unsung Great: Stories of Extraordinary Japanese Americans."

Takayoshi was the daughter of a mixed-race Irish and Japanese couple, which made her fate uncertain. After petitioning the Western Defense Command, she received attention from the right place. The President's wife, Eleanor Roosevelt, got word of Takayoshi's plight and wrote a letter in favor of her petition. The army provided her with an exemption so she didn't have to relocate to a camp for incarceration, but this proved a bittersweet victory.

You see, Takayoshi was married to a Japanese American man with whom she had two small kids. Despite her granted request, the military ruled her husband and children had to relocate to a camp. No exemptions would be made because the army feared letting the Takayoshis free might set a bad precedent for other Japanese Americans. Rather than face a life without her family, she willingly abandoned her freedom following them to the Minidoka relocation camp in the Northwest.

Ernest Kinzo and Toki Wakayama

Another Japanese American couple that defied internment rulings was Ernest Kinzo and Toki Wakayama, according to the Densho Encyclopedia. The Wakayamas lived in California, and they understood that somebody had to make a stand to bring the discrimination against Japanese Americans to an end. So, they reached out to the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) to launch a legal battle against the various restrictions, regulations, and incarceration their community faced.

As an American Legion officer and WWI veteran, many thought Ernest Kinzo Wakayama had an especially good shot at winning their petition (via Peter Irons' "Justice at War"). After all, he was born in Hawaii and had also served as a precinct officer for the Republican party. He'd been a postal worker and secretary-treasurer of Terminal Island's fishermen's union. But as with the other resisters mentioned above, the American legal system moved excruciatingly slowly.

While the wheels of justice lagged, the Wakayamas struggled with incarceration at Santa Anita Assembly Center. As the months passed as prisoners, the couple became increasingly embittered and disillusioned by the treatment they faced simply because of their ethnicity. By February 1943, a miracle happened. Toki Wakayama's habeas corpus petition was granted, and they received a court date for a full hearing. However, the Wakayamas had already abandoned their case, seeking a return to the Empire of Japan rather than deal with further violations of their constitutional rights.

Lincoln Seiichi Kanai

Lincoln Seiichi Kanai was born in Koloa, Hawaii, and worked as a social worker with the Young Men's Christian Association (YMCA), according to the Densho Enyclopedia. His interconnection with the local community made him a natural advocate for Japanese Americans in the months after the attack on Pearl Harbor. As a critic of Executive Order 9066, Kanai vigorously opposed the targeting and relocation of Americans of Japanese descent.

Strong convictions motivated him to act although this placed his personal freedom in jeopardy. He refused to leave San Francisco after the evacuation of Japanese Americans was announced with the enactment of Public Law 503. His case never became as well-known as some of the other Japanese Americans who resorted to legal action. Nevertheless, it marked one of only 12 legal challenges to the evacuation order. Kanai's civil disobedience set an important precedent within the Japanese American community. "At a time when community and family pressures forced many Nisei to comport with an overwhelming posture of quiet compliance, Lincoln Kanai boldly faced potential ostracism and intimidation in order to lay claim to his constitutional rights."

In court, he battled against Public Law 503, joined by a handful of other people who also challenged the evacuation order. Not only did they go against the mainstream, but they hoped to use the legal system to secure redress. Instead, officials rewarded Kanai's efforts with a six-month prison sentence.

Tsutomu Ben Wakaye

Not all resistance started before incarceration as illustrated by Tsutomu "Ben" Wakaye, per the Densho Encyclopedia. Originally from Honolulu, Hawaii, he and his family relocated to San Francisco when he was a grade schooler. After graduating in 1931 from Galileo High School, he apprenticed in his dad's carpentry shop while also working at a trading company of Japanese goods. Eventually, he left behind artisanal handicrafts and retail for a position as an insurance salesman.

But everything changed for him during World War II. After cooperating with the government,+++ Wakaye ended up at Heart Mountain concentration camp. There, he met Frank Emi and other powerful leaders of the Fair Play Committee, a camp-based draft resistance movement (via Conscience and the Constitution). Soon, he rose to prominence within the organization, acting as the organization's treasurer because of his insurance background.

When Wakaye got called up to report for the draft, he was a no-show for the physical. He also helped other men facing a similar fate to resist. These actions landed him in prison for aiding and abetting other draft dodgers. All told, he received a three-year sentence for evading his own draft and two years for assisting others in doing the same. In 1947, he walked out of Leavenworth after finishing his sentence. But life as a free man wouldn't prove easy. He had trouble securing employment and eventually ended up a janitor before dying in 1952 from kidney failure.

Kiyoshi Okamoto

Kiyoshi Okamoto was a native of Hawaii who completed two years at the University of Hawaii where he studied engineering and chemistry, per Reference. After leaving the university, he worked at a sugar mill as a superintendent before relocating to San Pedro, California, as a soil engineer. He worked on introducing papaya to the "Golden State." In 1929, after the stock market shakeup that ushered in the Great Depression, Okamoto became a high school teacher in Los Angeles where he stayed until 1942. Described by many as a loner, he never married and didn't have any children.

After arriving at Heart Mountain concentration camp in 1942 at the age of 55, Okamoto immediately got to work. He was among the first Japanese Americans to demand redress for the loss of constitutional rights in the wake of Pearl Harbor. He sent countless protest letters where he discussed the deprivation of basic civil liberties that had become the new reality for Japanese Americans.

His efforts didn't prove in vain as he brought national attention to the plight of his community in wartime America. But his advocacy didn't end there. He also actively fought for due process while opposing corruption in concentration camps. Starting in 1943, he organized resistance to the Selective Training and Service Act, which involved the conscription of men being held in concentration camps. Okamoto would end up serving time in Leavenworth before having his sentence overturned in 1946 on appeal.

Mrs. Tien Gee

Not all Japanese Americans ended up in concentration camps, but it took a village to keep them free. Take, for example, the case of Mrs. Tien Gee who was married to a Chinese American and lived in Los Angeles' Chinatown, according to John J. Bukowczyk's "Immigrant Identity and the Politics of Citizenship." After President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed the executive order that launched the incarceration of so-called enemy aliens, Tien Gee disappeared into her husband's Chinese community.

Yet, this didn't stop the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) from tracking her to the Chinatown hair salon where she worked. After federal agents arrived, they asked the hairstylists and customers working at the salon about Mrs. Tien Gee's location. But everyone feigned ignorance, including Mrs. Tien Gee. The men in black never figured out that she was standing right there, cutting hair while she answered their questions.

Because of her marriage to a member of the Chinese community, Tien Gee benefited from this network of protection. As Bukowczyk notes, "The willingness of Chinatown residents to encircle the Tien Gees underscored war's success in revising community attitudes about ethnicity and race, especially among Asian groups."

Joseph Yoshisuke Kurihara

After spending the first two decades of his life in Hawaii, Joseph Yoshisuke Kurihara moved to San Francisco. There, he enlisted in the United States Army and served overseas in France during World War I (via the Densho Encyclopedia). After the end of the Great War, he moved to Los Angeles where he lived and worked until the passage of Executive Order 9066, which turned his life upside down. Soon, Kurihara found himself at the concentration camp in Manzanar.

Although stomaching incarceration was hard enough on Kurihara, he would be thoroughly disgusted by the actions of his fellow Japanese Americans. After meeting Mike Masaoka, he learned that the field secretary of the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL) was actually cooperating with the government in its incarceration of members of their community. Concluding they were "a bunch of spineless Americans," Kurihara determined to find these so-called community leaders and oppose them. This led to violence at Manzanar and his relocation to an isolation camp in Moab.

How history sees Joseph Yoshisuke Kurihara reputation remains a mixed bag. Painted both as a hero and villain, he asked for redress from the American government for unjust treatment starting in 1943. Embittered by his experience, he relocated to Japan after the war ironically working as a translator and interpreter for the US military.