The Untold Truth Of The Texas Rangers

Among law enforcement agencies in the United States, the Texas Rangers are one of the most well-known and distinctive. They have extensive duties within the state of Texas, including investigating major violent crimes, corruption, cold cases, and police shootings (via the Texas Department of Public Safety). They are also tasked with helping provide security along the Texas-Mexico border, and they often partner with the U.S. Border Patrol and target Mexican cartel drug smuggling syndicates.

Texas Rangers have immense forensic capabilities, including having trained hypnotists and artists, to both aid witnesses and help with facial reconstructions of skeletal remains (per the Texas Rangers Hall of Fame and Museum). They also provide security for the governor of Texas whenever the governor is on official travel throughout the state, and they do the same for visiting foreign dignitaries who request their protection.

Yet, there is still a lot even big fans don't know about the Texas Rangers and their history, such as who was the first Ranger to die in the line of duty? What was the Rangers' role in the Mexican-American War? Or what was the agency's role during the American Civil War? Just how long have the Rangers been around, and how many are currently active in Texas today? Read on to find out — this is the untold truth of the Texas Rangers.

The first Rangers were formed before Texas was a republic

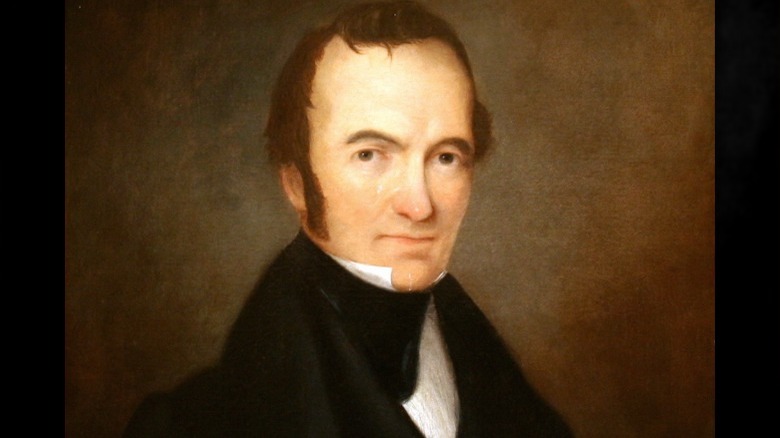

The Texas Rangers are known as one of the top modern law enforcement agencies in the United States, but they actually have a history that goes back 200 years — before Texas was even a republic or state! According to Mike Cox in "The Texas Rangers: Wearing the Cinco Peso, 1821-1900," their history begins back in 1821 in southern Texas. Mexico had just staked its independence from Spain that year, and American settlers were pushing their way into Mexico looking for new territory to settle. One of those settlers was Stephen F. Austin, the founder of the Texas Rangers.

In 1821, Austin had secured an "empresario contract" (via the Texas State Historical Association) to settle the land near Goliad, Texas, with American colonists, and after working out the details with the new Mexican government, he returned to his colony in August 1823. Austin knew the infant colony needed a security force to protect the settlers from local Native Americans and dangerous highwaymen. So, he decided to raise a gang of compatriots to supplement the meager force of militiamen that had been sent by the governor.

Austin's band was "to act as rangers for the common defense" of the colony, by repelling attacks from hostile locals. It is not known exactly which day Austin formally organized the force, but it is thought to have been around the first week of August, though it may have been a few months later in November when the Rangers started patrolling.

The first Texas Ranger to die on duty was John Jackson Tumlinson

Among the colonists who came to settle Stephen F. Austin's first colony in Texas in 1821 was North Carolinian John Jackson Tumlinson. Per the Texas State Historical Association, Tumlinson built his homestead in present-day Columbus, Texas, right on the Colorado River. He was even elected alcalde (magistrate or mayor) of the community. The safety and security of the colony and community were of the utmost importance to Tumlinson, who feared the effect local criminals and bandits would have on the town. However, in 1823, when he was on his way to discuss the state of security on the frontier with officials, he was murdered by a tribe of Waco Native Americans.

Tumlinson was the first Texas Ranger to die in the line of duty, and he is featured on a memorial plaque located in Pleasanton, Texas (via the Texas Historical Commission). His son, Capt. Peter F. Tumlinson, to whom the memorial is dedicated, followed his father's lead and became a Texas Ranger himself. Peter served as a Ranger for four decades, and among his career feats were fighting during the Texas Revolution and battling against Mexican outlaw Juan Cortina.

Texas Rangers fought in the Mexican-American War

Modern-day Texas Rangers are known as a law enforcement agency and police force, but they actually participated as soldiers during the Mexican-American War from 1846-1848. According to Doug Swanson in "Cult Of Glory: The Bold And Brutal History Of The Texas Rangers," many of them participated as troops for the U.S. Army. They stayed together and kept their Ranger regiments during their deployments, even going as far as to wear their old uniforms instead of Army-issued ones. They were fierce fighters, unmatched due to their advantage as mounted soldiers and employing a fierce "blood-curdling yell" during their attacks.

It was during this time the Rangers gained their famous nickname, Los Diablo Tejanos, or the Texas Devils, and they struck fear among many of their Mexican opponents. In a harrowing instance of violence during the war, one group of Rangers reportedly killed 100 civilians in Monterrey, Mexico (per the Bullock Texas State History Museum). As told in "The Texas Revolution and the Texas Rangers: The Bloodiest Decade, 1910-1920," the Rangers fought under famous generals Winfield Scott and Zachary Taylor. They fought for vengeance over the Alamo and relished the opportunity to hunt down Mexicans.

The Texas Rangers had many clashes with Native Americans

Even before the Mexican-American war broke out in 1846, the Texas Rangers were already at war with another enemy on the frontier — indigenous Native American tribes. Stephen F. Austin had originally created the rangers in 1823 to fend off Native warriors from his new colony, and by the 1830s, they were being officially put to work by the Republic of Texas to do the same thing.

In late 1838, the second president of Texas, Mirabeau B. Lamar, petitioned the republic's legislature, asking for a regiment of soldiers to protect the inhabitants along the frontier (per "The Texas Rangers"). The Republic's Secretary of War, Thomas J. Rusk, was already at work organizing several companies of Rangers, and within a few days, he had funding to create a specific Ranger regiment of 56 men. They immediately went on a raid against neighboring Comanche Natives and spent the next several years battling them around the frontier.

After fighting in the Mexican-American War, the Rangers once again went back to frontier security, supplementing the U.S. Army, which was officially in charge (via the Bullock Texas State History Museum). They went on several offensives against more Comanches, including a six-month expedition led by Ranger John Salmon "Rip" Ford in 1858. During the expedition, the Rangers fought at least 600 Natives, killing 80 and only losing one Ranger.

A unit of Texas Rangers fought for the Confederacy

Another aspect of Texas Ranger history that doesn't often get attention is their participation in the Civil War, in which they fought on the side of the Confederacy. A few months after the election of President Abraham Lincoln, in February 1861, Texas became the seventh state to officially secede from the Union (per History). Initially, the Rangers were not organized to fight in the war. Instead, they were to continue to be used as protection for communities on the frontier; however, late in the year, the new Texas Confederate legislature organized the 1,000-man "Frontier Regiment of Rangers," according to "The Texas Rangers."

When they began patrolling in early 1862, the Rangers ran into more Union soldiers than they did Native Americans. "I think we will have to abandon our Indian hunting and turn our attention to Yankee hunting," Capt. H.Y. Davis noted in July, and as the Civil War continued, Rangers indeed started to play a bigger role. Not only did famous Confederate commanders, like Robert E. Lee and Albert Sidney Johnson, start using the Rangers' techniques in battle, but they were finally officially absorbed into the larger Confederate Army in late 1863.

The loss of so many troops from Texas' control hurt the Rangers' ability to keep on frontier defense, and their raids became more and more dangerous. After the war, many of the Rangers kept their guns and returned to their homes and frontier security.

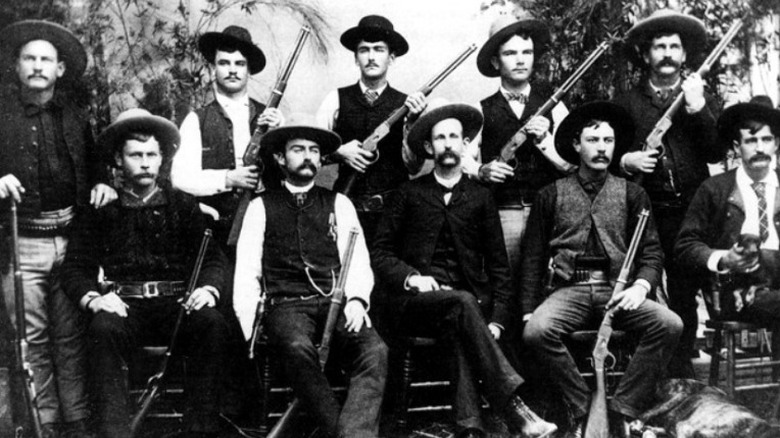

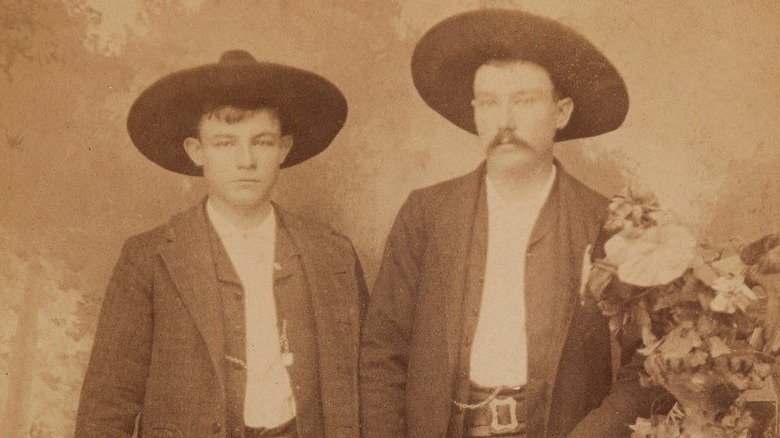

Their gunfights with wanted fugitive Sam Bass

Outlaw Sam Bass (above middle) is notorious among many Texans and Texas Ranger fans. In 2015, a movie was even made that was roughly based on his life, "Kill or Be Killed" (per The Austin Chronicle). However, for all the fanfare that Bass gets for his train robbing, few realize it was intense gun battles with the Texas Rangers that led to his death.

According to "The Texas Rangers," Bass had started his outlaw career a few years prior in 1876. In September 1877, he made a massive score of $60,000 from a train robbery in Big Springs, Nebraska. Trying to evade the heat from the robbery, Bass relocated to Texas with his gang.

After a few more robberies in Texas, the Texas Rangers started to pursue Bass and got into a long-range gunfight with him and his gang, but they narrowly escaped. A few months later, at Round Rock, the Rangers once again caught up to them. One Ranger was sitting in a barbershop when he heard gunfire erupting outside, and he ran out and began firing on Bass and his companions.

Bass was mortally wounded in the battle, and Rangers tracked a line of his blood for over six miles to find him on the verge of death. He died on July 21, 1878, at about noon. Bass was one of over 1,110 people the Rangers had captured or arrested in 1878, and one of just 28 casualties.

The Porvenir Massacre

One of the deadliest nights in Texas Ranger history was also one of its most disgraceful. In early January 1917, a group of Texas Rangers under Capt. J.M. Fox had gone to a riverfront settlement named Porvenir, according to "The Texas Rangers and the Mexican Revolution." The purpose of their trip was to "clean out a nest of bandits" who were living there, some of whom had reportedly been working as spies against the Rangers and may have participated in an earlier deadly raid in 1917. As the Rangers told it, while they were in the process of searching the village for stolen contraband from the 1917 raid, they suddenly came under fire from behind.

The Rangers returned fire, killing 15 Mexicans before both groups fled the area. Initially, the raid was not mentioned in Capt. Fox's dispatches, and it was later determined that instead of a mutual firefight, it was an execution. Contrary to the Rangers' reports, all of the Mexicans had their weapons taken and were "helpless prisoners" before the Rangers and their guns. One witness said the deceased "were innocent farmers not bandits."

After further investigation, Fox's company was completely split up. Five of the Rangers who participated in the raid were fired, while three others resigned, and the remaining seven were transferred to other companies. Capt. Fox himself resigned, and he was told by his bosses "we're not keeping men on the border to murder and kill."

They rigged elections in 1918 and committed atrocities

In the early 20th century, the southern border between Mexico and Texas was in a state of flux. Per Refusing to Forget, white Texan settlers had slowly been moving into the area over the second half of the 19th century, displacing people of Mexican descent within the larger cities — though they still held control in "border enclaves." However, as new railroad connections sprung up, white Texans increasingly started to push into these enclaves. Land values skyrocketed, forcing many indigenous landowners to sell to Texans, and many others were forced to give up their land after title disputes.

In 1915, the tension between the Texans and ethnic Mexicans turned incredibly deadly, and the governor of Texas sent in hundreds of Texas Rangers to restore order (via the Bullock State History Museum). However, they did anything but subdue the already simmering tensions. Rangers immediately started lynching and shooting Mexican prisoners and driving residents from their ranches and homes, according to Refusing to Forget.

Texas' governor appointed multiple "Loyalty Rangers" in each county, ostensibly to keep peace and monitor activity related to WWI. Yet, in Alice, Texas, these "Loyalty Rangers" suppressed almost 80% of the Mexican vote, and throughout the border area voting totals severely diminished for Mexicans. Mexicans stopped showing up at voting polls altogether, fearing the wrath of the deadly Rangers. The Rangers proved them largely correct, terrorizing Mexican-American officials and their families, and lynching others — sometimes more than once.

The Canales Investigation

Due to the reprehensible conduct of the Texas Rangers during the Mexican Revolution, a Texas state representative, José Tomás Canales, decided to take action. Canales was the only Mexican-American legislator at the time, and in 1918, he filed 19 misconduct charges against various Rangers for their behavior during the war (per the Texas State Library). In early 1919, Canales also filed a bill that would have seriously gut and radically restructured the Rangers — it included reducing the size of the force and requiring previous law enforcement experience, according to Refusing to Forget.

The bill never passed, but there were some changes made to the Rangers as the result of Canales' inquiry. The Loyalty Rangers and several regular companies of Rangers were disbanded and removed from service. New standards were also updated for recruiting policies and misconduct proceedings. Rangers had killed roughly 5,000 Hispanics between 1914-1919 in Mexico and got into countless bloodbaths, much of which was revealed during the Canales investigation, the Texas State Historical Association explains. Eventually, though, through these reforms, the Rangers were able to reshape their image starting in the 1920s and 1930s.

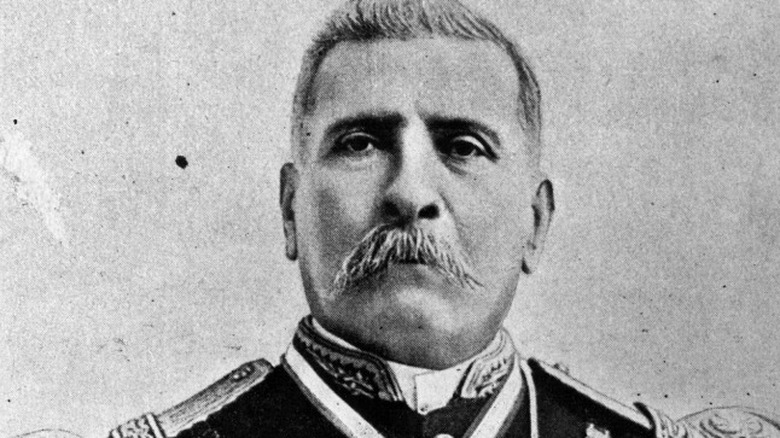

Several Texas Rangers prevented the assassination of a Mexican president

In October 1909, the presidents of Mexico and the United States, Porfirio Díaz (pictured above) and William Howard Taft, met for the first time in what newspapers called the "Most Eventful Diplomatic Event in the History of the Two Nations" (per the Texas State Historical Association). The meetings took place in El Paso, Texas, and Ciudad Juárez, Mexico, and they concerned economic matters. However, little did both presidents know, that serious trouble was brewing.

According to "The Secret War in El Paso: Mexican Revolutionary Intrigue, 1906-1920," security was tight. Among those on hand were 4,000 U.S. and Mexican troops, two police departments, numerous FBI agents and U.S. Marshals, and an entire company of Texas Rangers. In addition, a group of ex-Texas Rangers was also recruited as sharpshooters to protect the presidents during the scheduled parade.

Just before the El Paso meeting, Pvt. C.R. Moore of the Rangers apprehended a potential assassin. Moore and another man had noticed the suspect with what appeared to be a pencil sticking out of his hand, but when they subdued him, quickly realized the pencil was in fact a gun. He was there to shoot President Díaz, though no definitive motive was ever established and the suspect was never charged. The murder would likely have been an international incident, which the Rangers prevented with their quick thinking.

They tried to stop integration in Texas

In 1954, the Supreme Court decided the famous case of Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, which struck down racial segregation in public schools in the United States (via History). Today, the decision is celebrated as a landmark in the civil rights movement, and it is considered one of the most momentous in Supreme Court history. However, at the time it was incredibly contentious and controversial among many white Americans.

Per "Cult of Glory," many Texas business leaders and government officials, including the state's governor, expressed hostility toward the decision. A mob of 400 white men formed at the Mansfield High School, vowing to fight desegregation and assaulting an assistant district attorney. White supremacists burned multiple effigies on the city's main street — an ominous warning to African American students.

The governor ordered the Rangers to Mansfield — but not to protect African American students — instead, they were to protect the white protestors. He was quoted as saying the Rangers were sent not to "shoot down or intimidate citizens who are making orderly protests," and instead called the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) "agitators" and blamed them for the protests. The Rangers removed those spreading desegregation pamphlets, which they referred to as "inflammatory literature," and they even threw out a priest. As one NAACP lawyer put it, the Rangers were not on the side of justice, but rather were there to "protect the will of the mob."

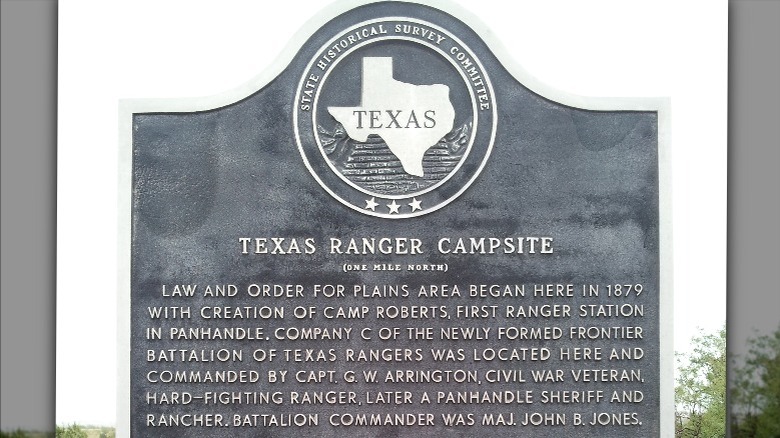

There are only 166 commissioned Texas Rangers

Since their inception 200 years ago, the Texas Rangers have gone through a dizzying amount of restructuring. From the 1820s through 1901, the Rangers were organized into several different iterations, namely as the Frontier Battalion and Special Ranger Force (per the Texas Rangers Law Enforcement Association). In 1901, they were officially named the Texas Ranger Force, and in 1935, the modern-day Texas Rangers were formed by the Texas legislature.

Though there are over 250 counties in Texas, there are only 166 active commissioned Rangers (as of 2020, via the Texas Department of Public Safety) — leaving less than one Ranger per county in the state. The entire Texas Ranger staff includes 234 full-time employees, many of whom work as support and administrative personnel. Most active and on-duty Rangers dress in civilian clothing, though they can be distinguished by their western-style hats and boots and Mexican-coin badges.

Their main headquarters is located in Austin, but the Rangers are actually split into eight separate companies. They are organized by geographical location, with companies in Houston, Garland, Lubbock, El Paso, Waco, San Antonio, and McAllen, Texas.

The Texas Rangers have their own Hall of Fame

The Texas Rangers have been involved in many high-profile cases and investigations, and in their 200-year history, countless men have put on Ranger badges and fought for Texas' freedom. Commemorating them is the little-known but fantastically organized Texas Ranger Hall of Fame and Museum in Waco, Texas. The museum was founded in 1964 and has welcomed over 4 million visitors since its official opening in 1968.

They have numerous educational programs, including for homeschooled children, and they even made a humorous parody of the movie "Night at the Museum," with "Night at the Ranger Museum." The museum is located at Fort Fisher Park, an homage to Ft. Fisher, which, in 1837, housed a company of Rangers. The original location of Ft. Fisher is unknown, as the only known information that has survived is that it was "near the springs of the Brazos [River]," and the park is located near the Brazos River in Waco.