The Controversial Truth About Henrietta Lacks

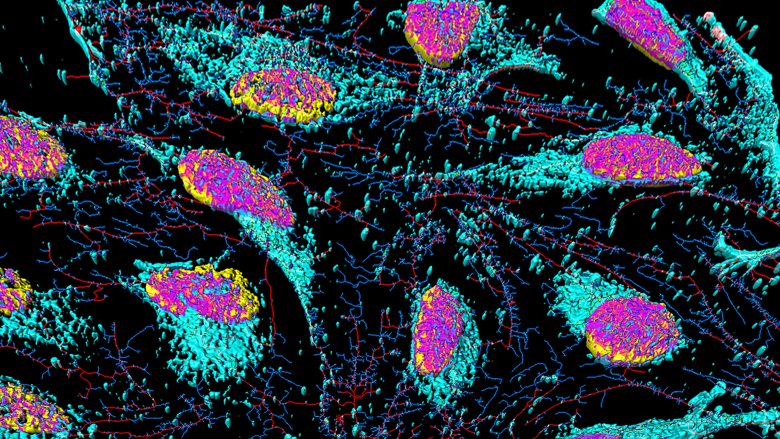

The history books don't spend a lot of time on the details, but many modern breakthroughs in medical science can be traced back to the cells of a poor black woman from Virginia named Henrietta Lacks. While her cells led to giant leaps in medical science and giant paychecks for pharmaceutical companies, her own kids lived in poverty. They didn't learn about how her cells (pictured above) were being used until decades after her death. Even if you fell asleep in biology class every day, you'll be intrigued by the story of this woman and the cells that outlived her.

Henrietta Lacks was a poor black woman and a mother of five

Henrietta Lacks's life was difficult almost from the start. Born in 1920 in Roanoke, Virginia, she lost her mom just four years later. Lacks then went to live in former slave quarters in an ancestor's plantation in Virginia with her grandfather and her cousin, David Lacks. She and David shared a room, one thing led to another, and they had their first son when Henrietta was just 14 years old. Henrietta and David tied the knot in 1941 and then moved to Maryland. By the time Henrietta was 31, they had four kids.

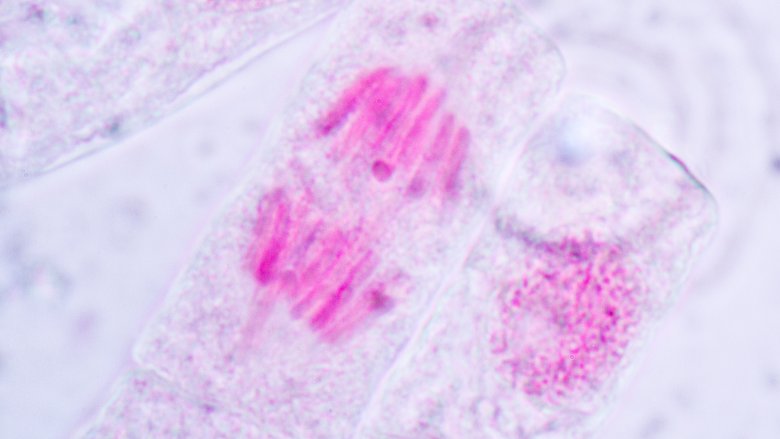

Her story took a tragic turn when, at the age of 30, in January 1951, she went to Johns Hopkins Hospital complaining of a knot in her stomach. Doctors quickly diagnosed her with cervical cancer and rushed to save her by literally sewing vials of radium onto her cervix. During her first radium procedure, the surgeon took a sample from Lacks's tumor — a tissue sample that would change the face of medical science.

The amazing cells

The surgeons gave Lacks's tissue samples to the lab of one Dr. George Gey at Johns Hopkins, who discovered that they replicated more quickly than any other samples he'd seen. Gey was obsessed with finding a cure for cancer. He and his wife, Margaret, had already spent almost 30 years trying to cultivate a replicating cell line that could be used in cancer research. While all the other cells he'd tested had died, Lacks's cells quickly grew into a sheet thicker than any he had seen before. The HeLa cells grew so quickly they could be transported on a speck of dust and take over existing tissue samples. Gey felt like a kid on Christmas morning.

In less than two years, Lacks's cells, which Gey named "HeLa cells," were being packed in ice and shipped all over the world. Gey also distributed some samples himself, flying out to meet researchers with test tubes tucked into his breast pocket like a true science geek.

Her cells opened up lots of new scientific possibilities

Let's focus on the good things first. Lacks's cells made all sorts of new experiments and research possible. For the first time, researchers were able to study the live human body without having to tamper with an actual live human, a big boon to us living humans. Researchers could study cell division, look at how viruses interacted with cells, and expose the cells to diseases in order to research the results — something they'd never be able to do inside a human body. Medical research and biological study could finally be combined.

HeLa cells were also used to study how human cells would react in extreme circumstances. Scientists have exposed HeLa cells to zero-gravity conditions, extreme heat, and nuclear fission, which are, again, pretty hard to test (ethically) on living humans.

Because of the myriad uses of HeLa cells, they've been mass-produced for scientific research. According to Robert J. Ursano, a professor of psychiatry and neuroscience, scientists have grown at least 20 tons of HeLa cells (there are trillions of them living in labs around the world) and they've been used in almost 11,000 patents.

HeLa cells have saved millions of lives

Before HeLa cells, scientists spent more time trying to keep cells alive than actually researching the cells themselves. But the robust HeLa cells have now saved millions of lives. Most famously, massive amounts of HeLa cells were used to test Jonas Salk's polio vaccine. Due to the vaccine, polio has been eliminated in most of the world, which is why no one you grew up with died from polio.

While polio is one of the most famous diseases cured through the use of HeLa cells, it's far from the only one. In the 1980s, a German virologist, Harald zur Hausen, found that HeLa cells contained a dangerous strain of HPV. Scientists later used his research to develop HPV vaccines, lowering cases of HPV in teenage girls by nearly 66 percent. That's great for teenage girls, since being one is hard enough without HPV.

HeLa cells were also used to create the medical field of virology, which lets scientists study the spread of diseases such as HIV and Zika. Scientists recently made the surprising discovery that Zika cells cannot multiply in HeLa cells, which could lead to a treatment for the disease and put another feather in the cap of Henrietta Lacks.

The fast growth of her cells led to her death at age 31

HeLa cells, for all the good things they did, also led to Henrietta Lacks's early death. While Gey was celebrating the discovery of endlessly replicating cells, Lacks's health rapidly went downhill. Those same cells that replicated like crazy in test tubes also grew fast — superhero kinds of fast — in Lacks's body. Toward the end of her life, she was so ill that her children weren't allowed to visit her. Her husband, Day, would bring them to a garden across the street from the hospital to wave up at her in her hospital room.

Just nine months after she first checked herself into Johns Hopkins, her tumor had taken over most of the organs in her body. She died at just 31, on October 4, 1951. Rebecca Skloot's book, The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, in 2011, recounts the difficulties Lacks's children experienced after her death. Soon after she passed away, Day invited a cousin and his wife, Galen and Ethel, into their home to take care of his five children. The couple treated the children badly, especially Joe, whom they physically abused and isolated from the other kids. Galen sexually molested Deborah, and she struggled with emotional scars from her experiences for many years afterward.

What became a miraculous discovery for science was also a tragedy for the Lacks family. Scientists and researchers who only see the HeLa cells in the lab may forget that they come from a real human with a family — a family that suffered because of those fast-growing cells.

The ethical dilemma

The use of HeLa cells has also brought up ethical questions about the treatment of patients and informed consent. According to the Society for History Education, surgeons took samples of Henrietta Lacks's cells without her knowledge or consent, a common practice in the '50s, especially at Johns Hopkins, where poor African-American patients were given free health care with the unspoken condition that their bodies could be used for medical research during treatment. The field of biomedical ethics didn't exist yet, and there were few laws to protect Lacks's rights.

Luckily, we're better protected now, because of many new policies that protect patients' rights, like the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki that laid out basic ethical principles for medical research. In 1991, the Common Rule was passed, which requires doctors to tell people when they are participating in research and to give them a consent form. Lacks wasn't given any such form, and doctors never treated her as an intelligent woman who deserved to have a say in the use of her tissue for research. Doctor knows best, right?

Her family wasn't told how scientists were using her cells

Unfortunately, these policies didn't help Lacks's children, who didn't hear from doctors until 1973, over 20 years after HeLa cells were first harvested. The children were asked for blood samples in order to study their genetic makeup, but the researchers still didn't ask for consent or clearly tell them how their mother's cells were being used. In fact, at the time, the kids thought they were being tested for cancer. Deborah worried for months that she would die from the same cancer as Henrietta. While the scientists benefited from the Lacks line again, the Lacks were left confused and frustrated, a common theme in this story.

It wasn't until Rebecca Skloot wrote her best-selling book, The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, that Lacks's children learned the full story. Skloot was the first person to focus on the story of Henrietta Lacks the person rather than just HeLa cells. Her book came out in 2011, a full 60 years after Lacks's cells were first used in medical research, which is a pretty long delay for any sort of recognition.

Her kids were never paid for the use of her cells

Even after Skloot's book was published, Lacks's children never made a cent from her cells, which have been reproduced and sold in the millions. As recently as February 2017, her son Lawrence unsuccessfully asked for compensation for the use of his mother's cells, according to the Washington Post. "My mother would be so proud that her cells saved lives," he said. "She'd be horrified that Johns Hopkins profited while her family to this day has no rights." In response, Johns Hopkins released a statement that the hospital never patented HeLa cells, does not have the rights to them, and didn't profit from the distribution, either.

But even if Johns Hopkins didn't benefit financially from the cells, others have. Cell banks and biotech companies have sold HeLa cells for huge profit, with vials of the cells going for over $250 a pop. Lacks's children haven't been so lucky. When Skloot reached out to the Lacks family to write her book, all of them were sick, but none of them could afford medical insurance or treatment. Lawrence asked Skloot, "If our mother is so important to science, why can't we get health insurance?" Shouldn't kinda saving the world involve a reward of some sort?

Scientists published the genome for HeLa cells online without the consent of her family

Even after Skloot published The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, the Lacks children still had to deal with scientists violating their rights. According to Nature, a team of German scientists headed by Lars Steinmetz published the genome for HeLa cells online without the family's permission in 2013. This led to an outpouring of criticism from the family, scientists, and bioethicists. The genome revealed sensitive genetic information about Lacks's living family members.

Steinmetz and the team, based at European Molecular Biology Laboratory in Heidelberg, had no idea that publishing the genome, which was completely legal, would cause such an uproar. They had published the genome because they saw it as a helpful resource, but when they realized the upset it was causing, they removed the data from public databases. "We wanted to respect the wishes of the family, and we didn't intend to cause them any anxiety by the publication of our research," Steinmetz said. Once again, scientists showed how clueless they were when it came to protecting the rights of private citizens.

The incident led to an agreement between the U.S. National Institutes of Health and the Lacks family. Family members David Lacks Jr. and Veronica Spencer now sit on the board that approves all federally funded studies involving HeLa cells. After nearly seven decades, they finally got a say in how their mom's cells are used. Now if someone would just work on that compensation thing.