Artist Claes Oldenburg's Most Controversial Pieces All Share An Unexpected Appearance

Lots of folks have trouble wrapping their heads around modern art. "What's that?" people ask. A shoestring? A blank, white square? Half a broken toilet bowl filled with a cross-section of chicken soup in the bowl, but the chicken pieces are actually little fish with human faces? (That last idea is ours — don't take it.) Many people shake their heads, shrug their shoulders, and say, "I don't get it. What's the point? Why should I care?" By and large, when people ask this question, they're really asking one of art's most age-old questions: "Why is that thing art?" Or, more broadly, as Russian author Leo Tolstoy once called his landmark 1897 essay, "What is Art?" (via The Collector).

There's a simple, self-aware, self-commentary at play in pieces like the above-mentioned shoestring. Sometimes artists are trying to provoke the very questions posed above. Sometimes that's the point, and not the more classical, even Greco-Roman vision of art as idealizing humanity and its accomplishments. Rather than stand in support of an idea, an ethic, a cultural identity, etc., sometimes art exists to upend or scrutinize it, especially since the Industrial Revolution and, specifically, 1860s France (per Art in Context).

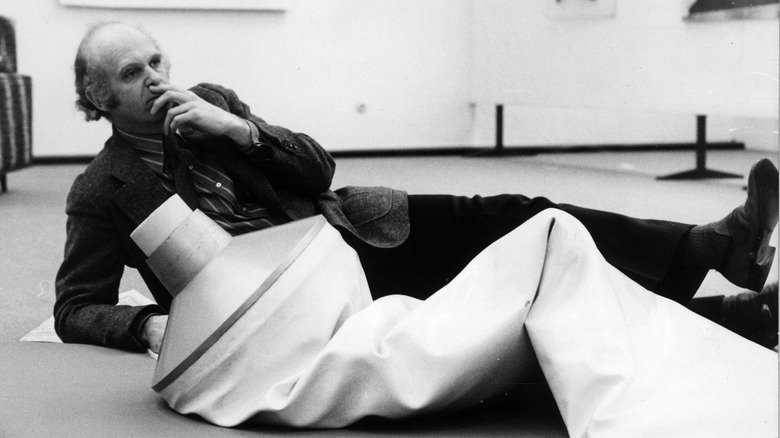

But some folks, plainly put, are not going to think about all this. They just want to be delighted, or moved somehow. This is where recently deceased artist Claes Oldenburg — who bridged the gap between "accessibly human and more cerebral," as The Washington Post puts it — comes into play.

Big, bright, and whimsical

Even after seeing only two or so of Claes Oldenburg's works, a very clear pattern emerges. Super big, super bright, and often, well ... food. Take 1962's "Floor Burger, Floor Cone, and Floor Cake," shown at the Museum of Modern Art and described as "large-scale soft sculptures" whose names alone are bound to make folks chuckle. Oldenburg took everyday, common objects and ballooned them into "colossal monuments," as The New York Times quotes. He also often installed them in public places requiring a lot of space. Or, as Oldenburg told the Los Angeles Times in 1995, "Art had to mean more than just producing objects for galleries and museums. I wanted to locate art in the experience of life."

Perhaps this is why Oldenburg's work has a magical, childlike, cartoonish quality to it. If so, it's not too hard to see why folks have taken to it over the years. Oldenburg made hundreds of works all across the world: bowling ball and pins in Eindhoven, Netherlands (above); an ice cream cone on a roof corner in Cologne, Germany; a saw stuck in the ground in Tokyo, Japan; a crushed cigarette in London, England (via The Guardian); a giant clothespin in Philadelphia, U.S. (per the Association for Public Art), and many more. His whimsy, strangeness, and dare we say "cuteness" has made people curious, laugh a bit, think a bit, and then head on their way. Maybe this was Oldenburg's answer to the question, "What is art?"

Escape from a desk job

As Deutsche Welle says, Claes Oldenburg was born in Stockholm, Sweden in 1929. At a young age, there were no indications that Oldenburg would head off in his chosen direction. However, his family was well-to-do enough — his father was a diplomat, his mother an opera singer — to allow their son to pursue his own path.

When Oldenburg was 7 years old, his family headed to the United States. Oldenburg went on to study literature and art history at Yale and then followed his growing interest in art further by studying at the Art Institute of Chicago, as Guggenheim explains. While in Chicago, he actually took up work as a police reporter, of all things, at the City News Bureau of Chicago. He was promoted to editor, but rather than "grow stale behind a desk," Oldenburg decided to strike out and do what he really wanted to do.

In 1956, he moved to New York, got involved in artistic circles, and by 1959 had started to develop his signature style. That year, the Judson Gallery displayed a collection of his work: "monstrous human figures to everyday objects, made from a mix of drawings, collages, and papier-mâché." In 1961, he opened an art studio with a name so understated and typically Oldenburg that it sounds like a written version of his artwork: "The Store." It recreated, inside an interior gallery, interiors from neighborhood grocery stores. Its food was all made of plaster.

A true non-troversy in the making

You might imagine that it's difficult to take issue with something as humorously ridiculous as a giant toothpaste tube. Well, you'd be wrong. Feverish political ideologies being what they are, someone was bound to misinterpret something. The site of the largest such Claes Oldenburg conflict? Cleveland, Ohio.

During the 1980s and '90s, the "Free Stamp" sculpture in Willard Park drew the ire of some locals who called it an "insulting joke foisted on the city by coastal elites and local power brokers," as the local news site Cleveland.com says. Some, bizarrely enough, even thought "free" was somehow a reference to the U.S. Civil War, as another Cleveland.com article quotes. Oldenburg said, "It's the idea of freedom in general. It has a lot of meanings. It's very open-ended."

To add to the non-troversy, the statue — which looks like an old-school, red rubber stamp — was originally a commission from the Standard Oil Company of Ohio (Sohio). At the time, it was going to be positioned at the base of the Sohio skyscraper in downtown Cleveland opposite the Soldiers and Sailors Monument. Oldenburg said the monument inspired the "Free Stamp" design, which Cleveland.com described as featuring a "slender, triumphal column rising out of a blocky, Romanesque-revival building." Sohio rejected the design for undisclosed reasons, and BP America took over the commission. They, too, rejected the design, calling it "inappropriate" with no explanation. The sculpture sat in a factory for five years before finally being deployed to Willard Park.

Too colorful, too sexy, too political?

In a general sense, some have taken issue with Claes Oldenburg's aesthetic, considering it intrusive or tacky. This started back in "The Store" days in the early 1960s, when Oldenburg says his colors became "very, very strong," as The Washington Post quotes. Others might find fault with Oldenburg's perspective on his work. For instance, Cleveland.com reports him as saying, "I am for an art that is political-erotical-mystical, that does something other than sit on it's a** in a museum." While it's a stretch to think of giant hamburgers and spoons as sexual, there's at least one instance when Oldenburg admits to the "connotations" of one of his sculptures. That sculpture, a large screw bent into the shape of an arch, was rejected because some thought it resembled a limp penis. To add to the comedy, it was going to be stationed in front of a government building, the Frank J. Lausche State Office Building in Cleveland, Ohio.

One time, however, Oldenburg did have a directly political theme in mind for one of his sculptures. In 1973, he pitched to replace the Washington Monument with a pair of scissors. "Like the scissors," he wrote (via The Washington Post), "the U.S.A. is screwed together. Two violent parts destined in their arc to meet as one." He envisioned it jutting up blades first, handles buried. Even just pitching this project might have been a gag on Oldenburg's part, as it's hard to imagine that he believed it could've been accepted.

A true artistic game-changer

At this point, it's hard to take seriously any criticisms levied at Claes Oldenburg, but it's even harder to remember how much of a game-changer his work was. The New York Times wrote in 2017 that it's easy "to forget just how radical his work was when it first appeared." None of his monolithic sculptures come across as ultra-serious or unapproachable. This is doubtlessly a big part of what drew people to his work and why it drew people into art who otherwise might not have been interested at all. Plus, his sculptures' presence in parks, plazas, and other public spaces makes them much more visible and physically accessible than if they were tucked away in museums. As Oldenburg said many times — such as in the Los Angeles Times and Cleveland.com — this was his goal all along.

That being said, some of Oldenburg's work is preserved inside galleries, specifically his older and smaller pieces. Some of these sculptures are housed at the Paula Cooper Gallery — such as a dual light switch and car doors made from canvas — and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, which houses his early career, soft-sculpture food items. Yet other exhibits are temporary, like the "Claes Oldenburg & Coosje van Bruggen" gallery, which lived at Palm Beach from December 5, 2020, to January 9, 2021. Van Bruggen was Oldenburg's wife, a Dutch art historian, artist, and critic who often worked with Oldenburg on his creations and died in 2009, as The Guardian reports.