These Ancient Greek Statues Have One Very Explicit Feature

Even today, it's not too hard to imagine some folks getting, shall we say ... "priggish" around Greek or Roman sculptures in the classical style. A sexually self-conscious person visiting Michelangelo's David in Florence, Italy might avert their gaze from some of David's stonier pieces. A parent might thrust an open palm over a child's eyes and blurt, "Why did they have to put the penis there?" The obvious answer is: that's what people look like. After all, what exactly is "explicit" about a commonplace, even passé piece of anatomy that billions of humans have? You might as well wonder why humanoid sculptures include fingernails or ears.

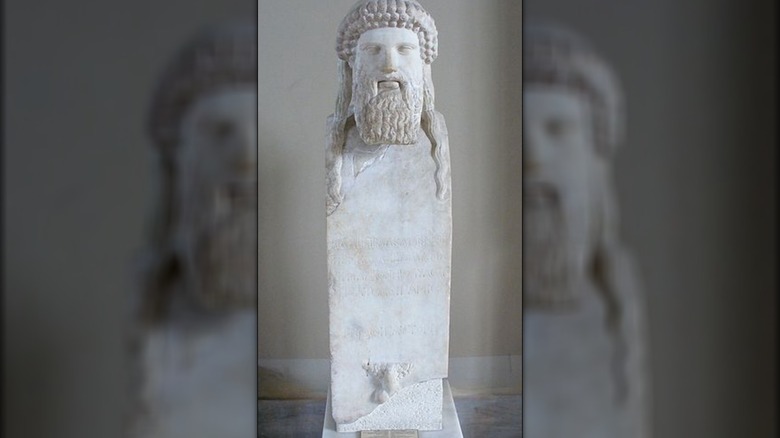

That being said, there are other, older sculptures from ancient Greece that raise the penile bar to full phallic. Most of the sculptures we think of as big, beautiful representations of idealized human beauty — the kind shown on Daily Art Magazine — are often associated with either classical Athens (5th century BCE) or the Italian Renaissance (15th to 16th centuries CE). Before the hewing of such regal figures, ancient Greeks crafted what are called "hermae" (plural for "herm" or "herma"). Hermae date back to at least 2,100 BCE, via the New England Garden Company, and rather than vanishing during the classic age, were crafted side-by-side along sculptures of newer styles and purposes.

Hermae often shared a similar, ahem, "stand-out" feature. Like the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Art History Glossary show, hermae often depicted not only penises, but penises grown fully erect.

A get-off-my-property penis

Hermae are unusually designed to say the least, even not taking their phalluses into account. They're more like four-sided pillars, or short, free-standing columns. The most basic ones, like a herm of the god Dionysus from 200 to 100 BCE on Art History Glossary, are just a head stuck on top of a rectangular plinth. The plinth is completely unadorned except for genitals located at roundabouts the correct height and location on a human body, as Designing Buildings points out.

At such a sight many might ask, "What in the world is going on here? Did the sculptors just get lazy and do the head and penis, but nothing else?" Not quite. Hermae go way back, indeed, possibly even to ancient Greek beliefs predating our polished Olympic pantheon stories. As Britannica says, hermae get their name from the Greek word "herma," meaning "rock" or "stone." They were used as boundary markers in ancient times to denote property lines, including individual homes, almost like a warning statue: "Herein lies virility." This makes sense, because as the Metropolitan Museum of Art says, ancient Greece was a pastoral and agricultural society with plenty of wandering goats and sheep.

Those familiar with Greek myth might also recognize the name "Hermes" in hermae. Hermes is a very odd, possibly pre-Olympian, fertility god who could travel anywhere, including the underworld. As Theoi says, he was mischievous, cunning, responsible for delivering messages, and yes, was the god of travelers, herds, flocks, and boundaries.

Wartime phallic vandalism

Hermae took a downturn in 415 BCE when a widespread rash of anti-phallic assaults robbed Athenian hermae of their manhood. That is to say, some (possibly giggling) vandals swept through Athens giving impromptu penectomies to the city's hermae. We can only assume that some folks found it funny, no matter the blasphemy against an ancient religious tradition. Even only four years later, by 411 BCE, the comedic Athenian playwright Aristophanes included quips about "hermokopidai" ("herm-choppers") in his play "Lysistrata," as the Bryn Mawr Classical Review quotes.

That being said, according to World History other Athenians saw only sacrilege against the Eleusinian Mysteries, a set of highly secretive religious rites related to the goddess of harvests and crops, Demeter, as World History also explains. Demeter, it should be noted, is one of those other Greek deities who smacks of earlier traditions, like Hermes, which helps explain why folks connected the hermae to her. But despite the citizenry of Athens calling for an inquiry and searching for witnesses to the crime, they were never able to pinpoint who was responsible.

However, the desecration of Athenian hermae happened right in the middle of the Peloponnesian War (431 to 404 BCE), which saw Athens and Sparta take up arms against each other and their respective allies. The hermae mutilation occurred on the eve of a campaign being launched against Syracuse, and some smelled sabotage from within. It might have worked to disparage the Athenians, because the campaign proved an absolute disaster.