The Untold Truth Of The Quaker Movement

For many people, the only thing that comes to mind when you mention Quakers is the benign smile of that guy from their long-forgotten tub of Quaker Oats. But is that white-haired man in a broad-brimmed black hat a real person? Well, no. PepsiCo, which owns the brand, maintains that the friendly man is completely fictional, though some have alleged he's inspired by William Penn, an influential 17th-century Quaker.

However, Quakers are very definitely real. Properly known as the Society of Friends, per Britannica, the Quaker movement began in England and came to prominence during the height and aftermath of the English Civil War (via the Christian History Institute). Quakers — so named for the divinely inspired quaking that took hold of believers' bodies during Friends meetings — drew the ire of religious traditionalists in their home country. With revolutionary ideas that did away with the need for ministers, forbade oath-taking, encouraged pacifism, and claimed that men and women were spiritual equals, it comes as no surprise that some feathers were seriously ruffled when the Quakers came to town.

Despite serious persecution, Quakers persisted and became prominent in both Britain and the colonies of the New World. Over time, the group became a diverse mix of people, many of whom became involved in progressive social causes and spread the word of Quakerism across the globe. This is the untold truth of the Quaker movement.

Quakerism began in 17th-century England

According to "The Quakers: A Very Short Introduction," George Fox was just 19 when he left home in 1634 — first working with a Baptist uncle and then spending time amongst the Parliamentary army during the English Civil War. Fox found himself dissatisfied with new religious ideas circulating amongst the Parliamentarians as well as Anglican orthodoxy. He came to believe that God was communicating directly with him, without the intervention of a middleman clergyman.

According to George Fox University, the Quaker movement officially began in 1652. In that year, Fox ascended Pendle Hill in Lancashire, England, where he saw a vision of white-clad people "coming to the Lord."

As "The Quakers" notes, Fox wouldn't have gotten far if he was a lone zealot. The success of early Quakerism relied on its followers and advocates who joined Fox, including the influential Margaret Fell, a Lancashire woman who was first converted by Fox, then, in turn, converted not only many of her family and servants, but became a published writer and vocal advocate for the cause. After her marriage to Fox in 1669, she became even more entwined with the movement and was referred to as the "mother of Quakerism" (via Oxford Bibliographies).

Quaker beliefs upended religious orthodoxy

Generally speaking, there were four core beliefs espoused by George Fox and other early Quakers, which carry through to modern Quakerism. According to "The Quakers: A Very Short Introduction," these include the idea that a believer has a direct relationship with God, a kind of collectivist way of managing the church, full spiritual equality for all, and a mandate to not only live as pacifists but to advocate for other social causes.

Quite a few of the beliefs espoused by Fox and his followers proved to be threatening to those outside the movement, especially the ones that decentralized authority and did away with the need for priests or set rituals. They also refused to take oaths, potentially placing them at odds with a firmly established social and legal system. As History notes, this even extended to lack of titles — a Quaker would have declined to call someone "Lord," for instance.

Today, as the BBC reports, some Quakers may even hesitate to say they're Christian. After all, they don't necessarily take the Bible as the direct word of God and don't celebrate traditional religious holidays like Christmas. Instead, some state that they are part of a "universal religion" that goes beyond earthly boundaries.

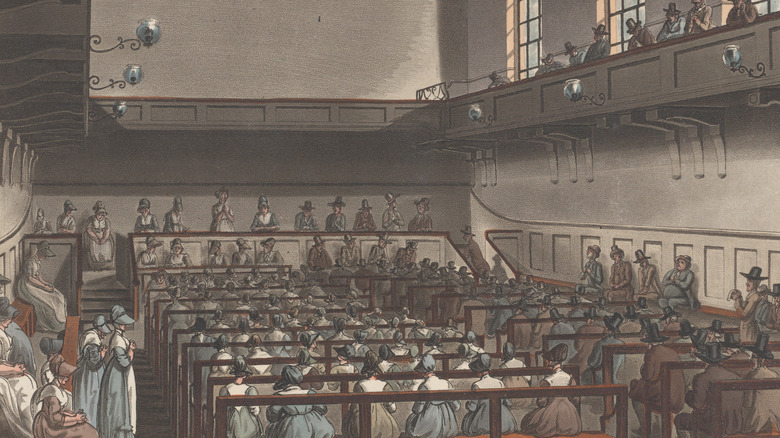

Traditional Quaker worship is silent

One of the most striking characteristics of old-school Quaker worship is its lack of structure. According to the BBC, it remains a radical departure from the regimented process of other religious services, which often incorporate preaching, hymns, and other liturgical hallmarks. Instead, Quakers simply sit in a room together, in a circle or square, for an hour. If the spirit so moves them, they may speak or bear witness in another way, but it's not a requirement. Otherwise, they sit in a meditative but collective silence meant to help worshippers gain a closer relationship with God.

This, as Quaker.org notes, is often referred to as an "unprogrammed meeting." Some Quakers might also take part in "programmed meetings," where a portion of the worship is led by one of the members, who might read a religious passage out loud or lead singing and prayer. The rest of a programmed meeting is still meant to be spent in silent communion with God.

"Meeting" can refer to this religious service, though the BBC notes it is also used to refer to groups of Quakers that assemble to take care of matters like business or church structure (though there isn't one governing body that tells all Quakers what to do). Mundane as some of these meetings may sound, however, they are nearly always understood as part of Quaker worship.

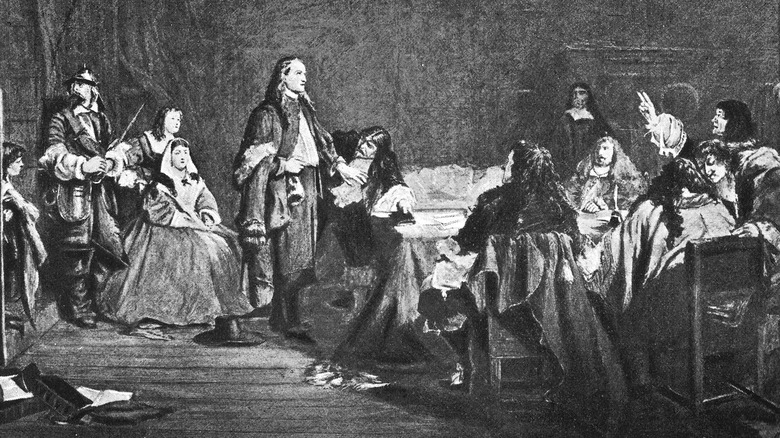

Many Quakers faced persecution

As with so many oddballs throughout history, Quakers were met with suspicion and confrontation. George Fox himself was subjected to beatings, including one incident where he was thrown down a set of stairs (via George Fox University). He was also jailed for preaching in the English city of Derby. He was offered an early out if he joined the army but, because of his pacifism, Fox declined. Another six months was tacked onto his sentence.

According to George Fox University, the Clarendon Code of the 1660s landed quite a few Quakers in jail for what were deemed to be illegal assemblies. As per Britannica, the Clarendon Code was a series of four acts that punished religious dissenters, the Quakers amongst them. The code put strict limits on their right to meet or minister, though the 1689 Toleration Act eased some of these intense restrictions.

The Clarendon Code might not have seemed all that bad to some Quakers in the North American colonies. As "The Quakers in America" notes, Puritans were often vehemently opposed to anyone who didn't believe exactly as they did, to the point where ship captains transporting Quakers to the colonies could face a fine. Some especially recalcitrant Quakers, including Mary Dyer, were even executed after defying a Puritan banishment.

Quakers have a complicated history with American Indians

Though today Quakers are often linked to progressive social advocacy movements, their history with marginalized groups is not as heartwarming as some may believe. Members of the Quaker movement often advocated for American Indian tribes in North America. They certainly pop up quite a bit in records of this nature, not least because they grew to have a fair amount of political power in the early United States, according to "Quakers and Native Americans." Others argue that the especially friendly relationships enjoyed between the two groups may stem from perceived similarities in their belief systems.

However, early Quakers' concept of "advocacy" turned out to be seriously harmful. That's because quite a lot of their early efforts were centered on assimilation via boarding schools. As per the Friends Journal, Quakers throughout the 18th and 19th centuries looked down on traditional tribal life with paternalistic smugness, writing of "the contaminating influences of the home circle" and the "indolent and untidy ways of their people." Their notion of "tidying up" unruly native children was to separate them from their families and enroll them in boarding schools that often focused more on manual labor than culturally sensitive education.

Pennsylvania was established by a Quaker

Though some of the earliest Quakers to migrate to North America faced serious persecution by unwelcoming Puritans, they gained enough power and respect to overcome their chilly welcome. In fact, one Quaker was so prominent that we have him to thank for the entire state of Pennsylvania.

It all sounds a little obvious, once you learn that the man in question was named William Penn. According to Aeon, he was a wealthy man who was born to a life of privilege in Ireland. Yet, having been drawn into the Quaker movement, he became a religious rebel and was kicked out of Oxford University in the 1660s. Like so many other Quakers, Penn was imprisoned for his beliefs and disowned by his more conventional father.

Yet Penn persisted in his newfound faith, becoming one of the most prominent Quakers of the day. He was also pretty canny, trading debt owed to him by the crown into a serious chunk of land. He set off for America in 1684, determined to turn his new landholding into a colony where everyone could get along. The rest of Penn's history, from his relationships with American Indians to his involvement in slavery, shows that he was a deeply complicated man.

Prominent abolitionists were also Quakers

Quakers were keen on talking up the spiritual equality of all people before God, but the fact remains that prominent Quakers like William Penn did own slaves (via Aeon). Furthermore, as the Friends Journal notes, slavery was common amongst Quakers at that time. Then again, Quakers were involved in the earliest known anti-slavery protest in the colonies, the 1688 Germantown Protest, which claimed that slavery was antithetical to true Christian belief.

As time went on, however, Quakers became more firmly established in the abolitionist cause. According to Haverford and Swarthmore Colleges, 18th-century Quakers were more ready to reject slavery than their 17th-century forbears. Some, like Benjamin Lay (also known as the "Quaker Comet") loudly and dramatically condemned those who would participate in the slave trade, including fellow Friends (via Smithsonian Magazine).

By the time of the American Civil War in the 1860s, some Quakers did participate in the Underground Railroad to transport fugitive slaves to freedom. However, as Haverford and Swarthmore Colleges noted, quite a few found themselves in a moral quandary — being fundamentally opposed to the institution of slavery, yet also to the violent war fought to free enslaved people.

Quakerism is linked to women's rights

As Quaker beliefs generally hold that men and women are spiritually equal, it was a natural progression from that ideal to the growing women's rights movement. Even some of the earliest adherents to the movement took a strongly feminist tack in an otherwise misogynistic world. Margaret Fell, an influential early supporter of George Fox (as well as his eventual wife), was a prominent activist and writer whose 1666 pamphlet, "Women's Speaking Justified," makes the Quakers' revolutionary stance clear (via the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy).

According to the National Park Service, members of the Society of Friends were part of the influential Seneca Falls Convention of 1848, widely understood to be the first known women's rights convention. Some of the organizers, like Lucretia Mott, were progressive Quakers who drew a direct line between their beliefs in full spiritual equality for the sexes and the need for earthly equality, too. Of those who signed the convention's Declaration of Sentiments, 23 were known Quakers.

Pacifism is a core tenet of Quaker belief

One of the most central beliefs of the Society of Friends, and perhaps the one that's gotten Quakers throughout history in the most trouble, is that of pacifism. According to the BBC, it's been part of the movement since nearly the very beginning. In a 1660 statement addressed to King Charles II, Quakers clearly stated their opposition to any and all acts of aggression, saying. "We utterly deny all outward war and strife and fightings with outward weapons, for any end or under any pretense whatsoever."

This is no passive sitting on the sidelines, either. While Quakers have historically made up a fair number of conscientious objectors during wartime, they have also been more active advocates for peace and nonviolence. Critics have sometimes equated this pacifism with buckling before morally corrupt and evil leaders. In response, chemist and peace activist Kathleen Lonsdale wrote in 1953 that Quaker pacifism did not require "the giving away of something that is not ours to give." Rather, she and other Friends maintained that nonviolent resistance was the far better answer.

Capitalism and Quakers have a tangled relationship

Because many early English Quakers were barred from getting academic degrees that would then lead to roles in politics or the legal system, quite a few of them went into business. Once there, as "Business Ethics from Antiquity to the 19th Century" notes, they earned a reputation for honesty. Their ethics stemmed from Quaker ideals, though one shouldn't discount the power of peer pressure as many participated in and observed the business activities of their fellow Friends.

That's not to say Quakers have an easy relationship with capitalism, no matter how much it's benefited some believers. Cadbury, the British sweets company of chocolate egg fame, began in 19th-century Birmingham under the aegis of John Cadbury, a prominent Quaker. According to The New Yorker, he founded the business with the intent to share profits with his employees and the larger community. Yet, his descendants were forced to compromise some of Cadbury's original morals to stay in business. For instance, they decided to advertise their product, even though he deemed ads to be little better than lies.

The 20th century saw growing division amongst Quakers

According to Britannica, abolitionism drew many Quakers closer to Protestant activists and began to color their own ideals. Groups of Quakers began to claim more mainstream ideas that weren't exactly championed by the Society of Friends, such as the notion that the Bible was the completely correct and divinely inspired word of God.

Disputes over these sorts of ideas caused some groups to drift apart. Some Friends claimed the Philadelphia Yearly Meeting was overly dominated by rich elders and therefore losing its Quaker cred. Others balked at the infiltration of mainstream ideas. One man, Elias Hicks, even went so far as to state that maybe the Bible needed to be discarded (only at God's behest, of course) in favor of newer, fresher scripture (via Britannica).

Hicks' loosely grouped followers became known by the early 19th century as the Hicksites. Their highly liberal views emphasized the Inner Light above the more traditionalist doctrine being adopted by Protestant-influenced Quakers in America. Soon enough, other Quaker trendsetters made their own unique views known. Their differences led to a major schism that can still delineate progressive and conservative Quaker meetings to this day.

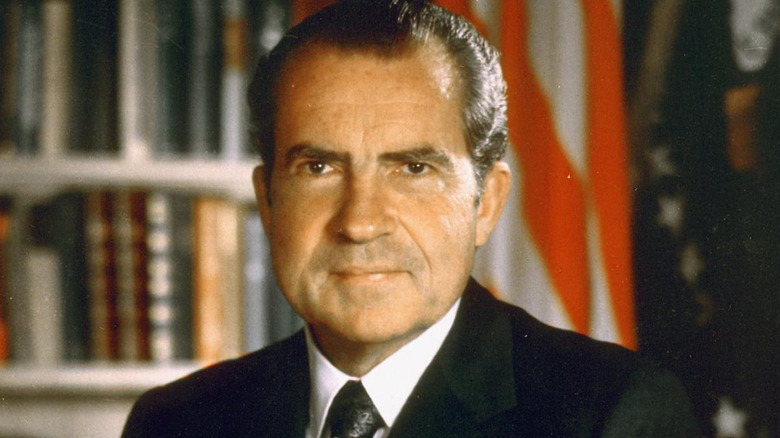

Two US presidents were Quakers

To date, two U.S. presidents were members of the Society of Friends, though a casual look at their policies may convince you otherwise. The first Quaker president, Herbert Hoover, was born a Quaker in 1874 Iowa. According to PBS, the Hoover family was devoted to their faith, though Hoover only made occasional references to his Quaker beliefs while campaigning on the Republican presidential ticket and during his time in the White House. He did reference Quaker religious persecution during a speech that called for religious toleration, and also contributed to the construction of a meetinghouse in Washington, D.C. Most notably, he refused to take an oath of office, instead choosing to make an affirmation that was more in line with Quaker ideals.

Though Quakers may or may not want to proudly claim Hoover (some blamed him for the Great Depression, as per the Miller Center), the other Quaker president surely has some picking their words carefully. Who is he? None other than Richard Milhous Nixon, whom PBS notes was part of an evangelical Quaker family. Nixon even attended Whittier College, a Quaker institution. However, the death of his brother in 1933, as well as a religion course he took at Whittier, seems to have profoundly influenced his beliefs and pushed him away somewhat from more traditional Quaker practices.

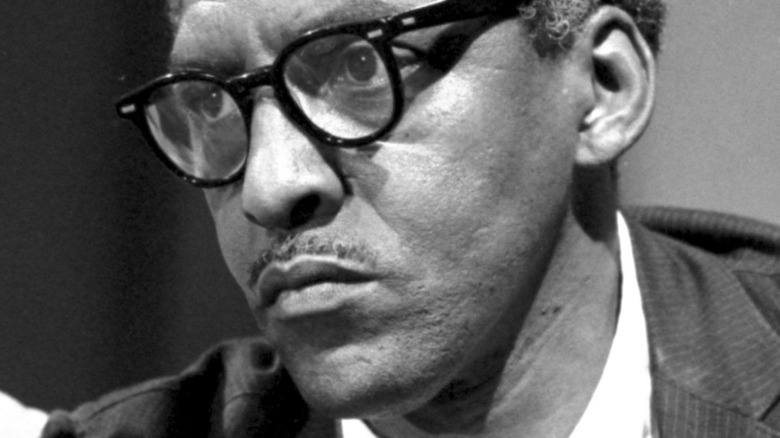

Quakers were part of the Civil Rights movement

Given the links between the Society of Friends and the earlier abolitionist cause, it may not be entirely surprising to learn that quite a few Quakers were involved in the 20th-century civil rights movement. As Forbes points out, Quakerism and civil rights were linked long before the 1960s, including the support of historically Black colleges and universities in the generations after the American Civil War.

Other Quakers were more directly involved. Bayard Rustin, one of the most influential members of the civil rights movement, was himself a Quaker, as per Inquiries Journal. Even though the Friends of his childhood were not quite as friendly as one might hope — meetings were segregated — Rustin maintained his faith. In fact, the Quaker commitment to pacifism directly influenced the nonviolent tactics championed by Rustin, who said that they were "rooted fundamentally in my Quaker upbringing."

Most modern Quakers are African

Though Quakerism began in England, the centuries have seen Friends in nearly all corners of the globe. Today, some estimates claim that more than half of Quakers live in Africa, as per the Friends Journal. That's due in large part to Quaker missionaries who traveled to colonial Kenya in 1902, making the future independent nation a center of African Quakerism. The open nature of the movement allowed some new followers to blend native shamanic beliefs with the religious structure of the Quakers (via the Friends Journal).

However, the beliefs of younger African Quakers may differ markedly from Quakers in other parts of the world. According to ReligionWatch, most Kenyan Friends take part in programmed worship complete with messages and hymns, sometimes referring to themselves as "noisy Quakers" (via Roads & Kingdoms).

Some core doctrinal issues have been up for debate, such as when progressive and conservative Quakers in the nation could not agree on the matter of same-sex marriage in a 2012 meeting. The differences are large enough that, according to Roads & Kingdoms, some Kenyan Quakers are considering taking steps to distinguish themselves even more from the old style of Quakerism.