The Untold Truth Of Hare Krishna

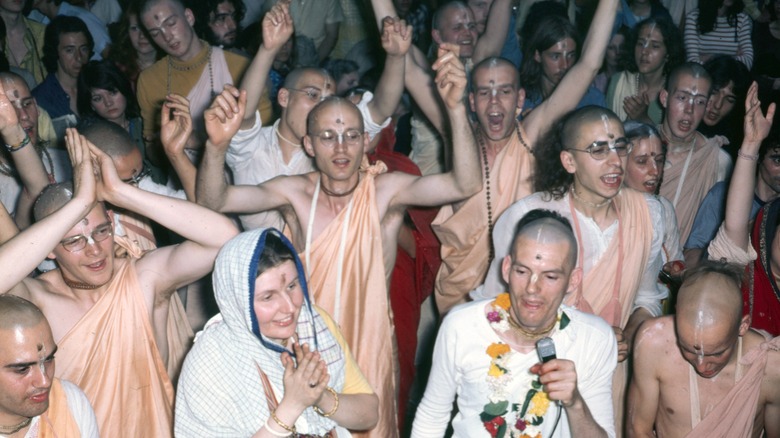

Followers of Hare Krishna stand out. They are typically seen chanting and dancing in public places — particularly on street corners and in airports where they can be seen by the greatest number of people. They are easily recognizable because of their bright orange robes and shaved heads.

As stated by The New York Times, at the height of the movement's popularity in the late 1970s, there were approximately 10,000 followers living on Hare Krishna communes in the United States. They gained prominence within the '60s and '70s counterculture, attracting the attention of many heroes of the hippie movement. Their appearance and chants were highly recognizable and were featured in popular movies, plays, and songs. Since then, former members have spoken out about what life was truly like inside Hare Krishna communes. Their numbers have significantly dwindled, largely due to some high-profile scandals about the Hare Krishna movement — including corruption, widespread abuse, and murder.

The name comes from their chant

The Hare Krishna movement is probably best known for the dancing and chanting that its followers often do in public places like parks, street corners, and airports. Whether in public or not, believers repeat this chant, sometimes for hours at a time.

As stated by NPR, the name of the movement comes from their most frequent meditative chant or mantra. They believe that this mantra is not only beneficial to say — it is beneficial to hear even if the listener doesn't know what it means. They believe that the vibrations of the words help to put an individual in touch with some deeper spiritual level of consciousness. This effect on listeners is the theological reason for why Hare Krishna devotees chant in public places (in addition to proselytizing and soliciting donations).

Hare Krishna is a type of monotheistic Hinduism, and many of its beliefs date back to 16th century India, as does the chant itself. The Hare Krishna movement, however, is distinctly Western and far more recent.

Hare Krishna was founded in NYC, 1966

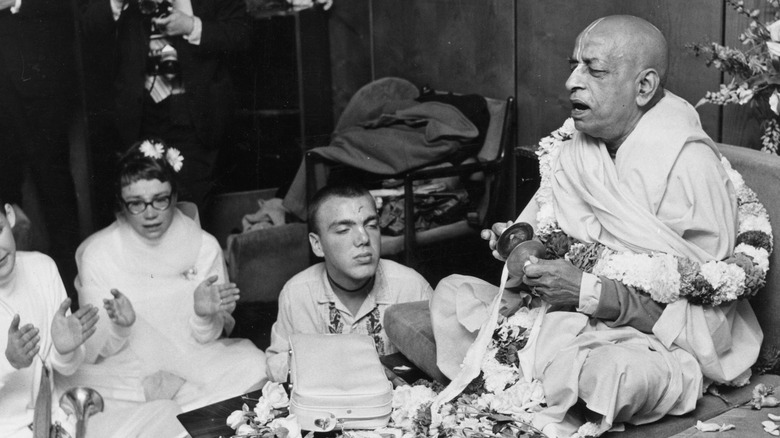

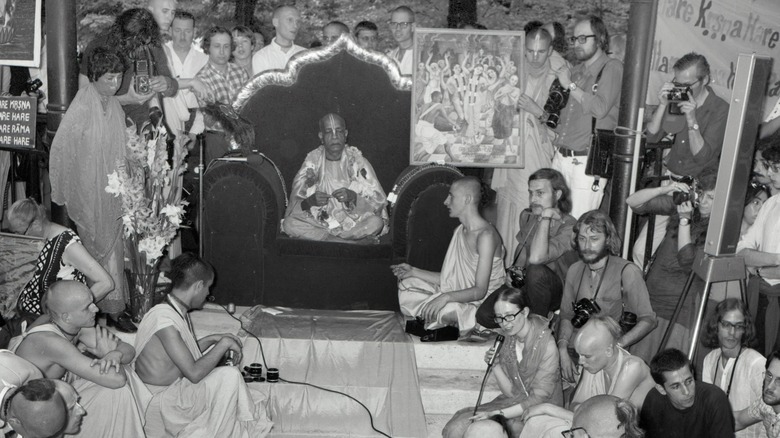

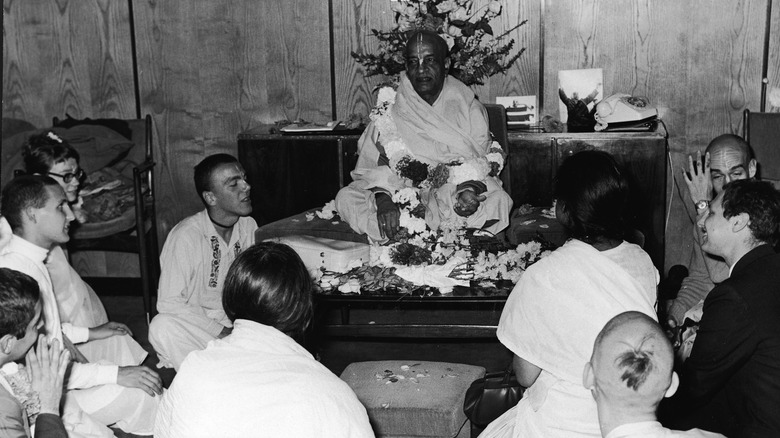

The movement's beliefs are based on Hindu doctrine, but the religion itself was founded in New York City's East Village in 1965. As described by The New York Times, the group's founder, A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Srila Prabhupada, was nearly 70 when he traveled to the United States as a stowaway in a cargo ship. Earlier in his life, he had been a part of Gandhi's famous civil disobedience movement and a follower of a Hindu guru. He came to the United States with the goal of converting English speakers. In 1960s New York, Swami Prabhupada found a hippie community that was primed and ready to learn about a new counter-culture.

Prabhupada, who had arrived in New York with less than $10, began organizing chants in Tompkins Square Park. He taught about self-improvement and spiritual development through "Krishna consciousness." Prabhupada founded a temple in an old gift shop on Second Avenue. This would develop into the International Society of Krishna Consciousness (ISKCON) or the "Hare Krishna Society." Soon, the group was bringing in significant money from donations, and it expanded across the country.

It was a part of the '60s and '70s counterculture

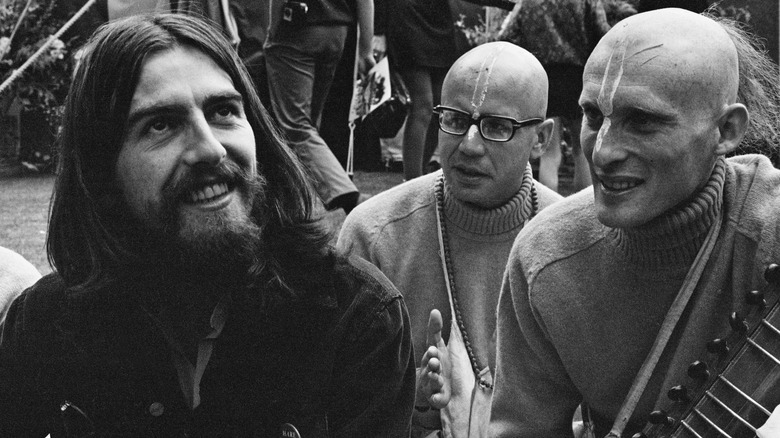

Swami Prabhupada arrived in New York City at the perfect moment to attract new followers. The vast majority of early Hare Krishna converts were young white hippies that were searching for something different. A new belief system that presented itself as an ancient Indian philosophy appealed to the era's dissatisfied youth. As described by The Washington Post, these new believers were willing to fully embrace a new way of living — one which was pretty significantly different from the free love hippie movement many of them knew before. The movement was extremely visible, with their followers dancing and chanting in orange robes in public spaces, and they drew in many donations and new followers — including many influential counterculture figures.

As described by The New York Times, one of the first celebrities to participate in Hare Krishna was the poet Allen Ginsberg, who told the press that the chanting had positively affected him. Lead guitarist of the Beatles George Harrison's first solo single was inspired by Krishna and included the Hare Krishna mantra. Bands like the Grateful Dead performed special benefit shows to raise money for the group.

It was a strict lifestyle

Even though the Hare Krishna movement often recruited hippies, life within ISKCON was extremely different from the culture of drug use and free love that the '60s and '70s are often associated with.

Hare Krishna had strict rules for its new devotees. As stated by Britannica, believers are expected to devote the rest of their lives to serving Krishna. They are not supposed to eat meat, drink alcohol, or take drugs. Sex before marriage is forbidden, and within marriage, it was supposed to be done only for the purposes of procreation, not for pleasure. In addition to wearing their bright orange robes, followers are supposed to wear a clay mark on their foreheads, and male followers are expected to shave their heads except for a single small tuft of hair.

In the '70s and '80s, devotees were expected to spend the majority of their time chanting in the streets and in airports. As described by The New York Times, for members who had children, this typically meant leaving their kids behind, sometimes with total strangers, so that they could devote their time to bringing in new members and soliciting donations. Devoted followers of Hare Krishna are expected to repeat their chant for hours each day — something that some former members argue was actually a brainwashing technique.

It was accused of brainwashing

In the '70s, several former members accused the Hare Krishna movement of brainwashing. As described by a report from The New York Times, they charged the movement with illegal imprisonment and attempted extortion. Ultimately, the State Supreme Court threw out the indictment, stating that because the Hare Krishna movement had not used physical force to keep members there, presenting an indictment would be a violation of freedom of religion.

While these accusations never went anywhere legally, chanting — like Hare Krishna devotees are encouraged to do for hours every day — can be used as an indoctrination technique. Psychologist and Organizational Culture expert Edgar Schein told Skeptic Meditations that chanting itself is not brainwashing, but periods of repeated chanting can make practitioners more vulnerable to suggestions — which can be dangerous if the wrong person is in charge.

Without legal recourse, some family members of people who had joined Hare Krishna resorted to hiring the services of cult deprogrammers. The most famous of these was Ted Patrick, who was frequently (and sometimes legally) accused of kidnapping individuals and subjecting them to days of sometimes brutal "deprogramming" to reverse apparent brainwashing.

Simple living turned into a gold palace

At one time, there were tens of thousands of Hare Krishna believers in the United States, but less than 1,000 lived on their communes (per The New York Times). As described in an article from The Washington Post, the largest of these was located in West Virginia. What began as a small spiritual retreat soon became an opulent tourist attraction.

One of the first converts to Hare Krishna was a Baptist minister's son named Keith Ham (often called "Kirtanananda Swami" or "Swami Bhaktipada" within the movement.) In the late '60s, Kirtanananda Swami began to put together a commune on rural West Virginia farmland called "New Vrindaban." The members lived over a cow barn, and their motto was "simple living, high thinking." Over time, however, it transformed into something closer to an onyx and marble palace. Soon the devotees were creating jeweled murals, crystal chandeliers, and stained glass to decorate what would become known as "the Palace of Gold." Eventually, the New Vrindaban had approximately 500 followers living there. It was the largest of any Hare Krishna commune. In 1979, it opened to the public. Ham, now known as "Kirtanananda Swami," became an extremely powerful and controlling figure within Hare Krishna — and was eventually at the center of the Hare Krishna movement's biggest scandal.

They admitted to abuse in boarding schools

Believers were often sent out to solicit donations. As described in The Washington Post, devotees were expected to travel to places where the public gathers, like airports and sports games, where they would chant and dance and collect donations. This practice made Hare Krishna very visible, but it also led to one of the first major scandals in the movement.

Believers who had children were not exempt from traveling to collect donations. As described in a report from The New York Times, they were required to leave their children behind, often at boarding schools in the care of other Hare Krishna devotees. In many cases, those assigned to caring for children were young and, for one reason or another, not considered qualified to interact with the public to solicit donations. They rarely had any experience or interest in childcare. Individuals who were forced to stay there as children have described being subjected to physical, emotional, and sexual abuse, as well as dangerous neglect. Former members who had stayed in a Hare Krishna boarding school testified that they were regularly beaten and not allowed to see a doctor. One described being threatened at knifepoint, while another was forced to sleep in a bathtub for weeks.

Most of this abuse took place in the 1970s and '80s, but it wasn't until 1998 that the Hare Krishna movement came clean about what had happened to the children in their care.

If you or anyone you know has been a victim of sexual assault, help is available. Visit the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network website or contact RAINN's National Helpline at 1-800-656-HOPE (4673).

A Hare Krishna leader had two followers killed

In 1996, Keith Ham, calling himself "Kirtanananda Swami," appeared in court with a smile. He was almost 60 and used a cane due to childhood polio. As described by The New York Times, the unassuming leader of New Vrindaban was involved in a racketeering scam that earned him millions and the murders of two Hare Krishna devotees.

New Vrindaban had become increasingly controversial. As described by The Washington Post, Kirtanananda Swami's charismatic leadership had turned controlling until he had almost complete control of the lives of those living in the massive commune. Despite protests, he began preaching some teachings that were not directly Hare Krishna at their regular services — which eventually led to the commune being excommunicated from ISKCON.

Kirtanananda Swami (Ham) was attacked by a visitor to New Vrindaban and spent more than a week in a coma. The commune became increasingly paranoid. Many believers carried guns, and Kirtanananda was often flanked by dogs. Two men were killed — believers who questioned the way Kirtanananda was leading the New Vrindaban. It is believed they were planning to expose Kirtanananda's abuse of young boys in the commune. The shooter later admitted that Kirtanananda Swami had paid him $8,000 for the murders.

The scandal grew

An FBI raid led to a federal grand jury charging Kirtanananda Swami (Keith Ham). As stated by The Washington Post, Kirtanananda was accused of racketeering, mail fraud, and conspiracy to murder. It is believed that he personally gained over $10 million. Although he spent months in prison, Kirtanananda's conviction was overturned. But that wasn't the end of the scandal.

Despite the accusations of murder, many of the believers at New Vrindaban continued to believe in the teachings of the man they called Kirtanananda Swami. Kirtanananda returned to New Vrindaban, but he was caught having sex with a teenage boy (via The Independent). His previously loyal disciples were forced to admit that Kirtanananda had been a participant in the abuse and corruption within the movement. In 1996, there was a retrial, and Kirtanananda pleaded guilty. He went to prison for eight years.

Hare Krishna never fully recovered from the scandals. Many believers stopped donating or left the movement completely when they heard about the abuses. Kirtanananda Swami had been at the center of the movement's fundraising scams, and without him, they stopped. The money was drying up.

The group became associated with scams

Scams have been a part of the Hare Krishna movement for a long time. As noted by The Independent, the money to purchase the land that would become the site of Hare Krishna's largest ISKCON commune, New Vrindaban, came from selling counterfeit merchandise. In addition to soliciting donations by chanting and dancing, believers were instructed to sell bootleg hats and bumper stickers with sports logos and cartoon characters on them. Selling these fake products ultimately brought in more than $10 million.

As described in an interview with a former member in WNYC, one of the most frequent ways of soliciting a donation was to trick or guilt people. First, a devotee would give a stranger a small trinket or a book by their founder, apparently as a gift. Then they would ask for a donation in exchange. If they gave a larger bill, it was almost impossible to get change without getting aggressive. "They put people in the position that they had to be almost rude and say, 'No, give me more money back," former member Steven Gelberg explained. "It became a very manipulative thing, and that really pervaded the organization."

Former members are speaking out

Former members have come forward about the abuses within Hare Krishna. As quoted in The New York Times, multiple individuals who were abused as children at Hare Krishna boarding schools came forward. Since then, others have discussed ways that even the fundamental spiritual practices of Hare Krishna can be harmful for some individuals. Many describe Hare Krishna as a cult.

Former member and author Henry Doktorski was at first attracted to the Hare Krishna movement's nonviolence and vegetarian philosophy — but he was drawn into the movement because he saw his "guru" as a father figure. He spent 15 years as a devotee of Hare Krishna, and now describes it as a cult. In an interview with "MythVision Podcast," he explained that he was in Hare Krishna at the time of the murders and had met the people who were killed, but it wasn't until he moved away from the commune that he learned the truth about what had happened.

On the podcast "Trust Me," former member Sam Harris described how while meditation is extremely popular in the United States and beneficial for many, it can be unpleasant and even dangerous for others. Some who meditate for long periods of time, as Hare Krishna devotees were expected to do daily, may experience mild auditory and visual hallucinations, an increase in anxiety and depression, or even depersonalization or realization.

The movement is dying out in the United States

After the death of the movement's founder Swami Prabhupada in 1977, ISKCON split into three groups. Their prime Manhattan real estate was sold off, and one group moved to upstate New York, one to New Jersey, and one stayed in Brooklyn. As described by The New York Times, the Brooklyn temple was initially successful, but in the wake of the scandals in the late '90s, Hare Krishna lost the vast majority of its devotees.

As stated by The Washington Post, New Vrindaban is back in ISKCON, and believers still come to chant there on weekends. It is no longer the massive commune that it was, which is not unusual for the Hare Krishna movement of today. Modern Hare Krishna congregations in the United States are not particularly strict. They are now primarily attended by Hindu immigrants to the U.S., who see an opportunity for community and culture at the temples, rather than a new counterculture and lifestyle like the young white American hippies of the '60s and '70s were looking for. There are very few full-time Hare Krishna followers left in the United States.