The Controversial History Of Marijuana Legalization

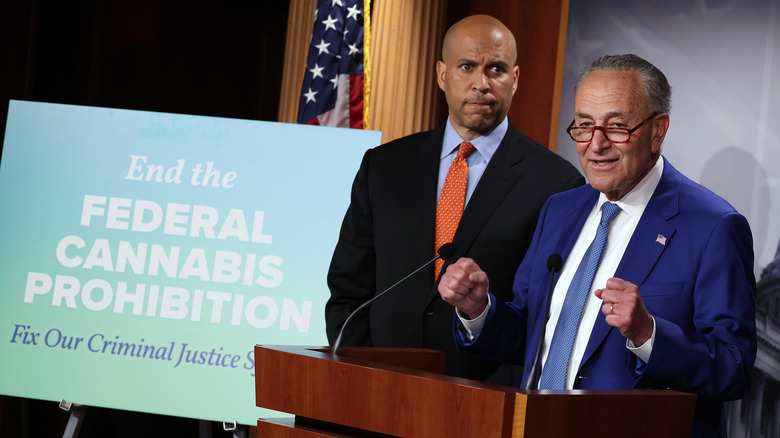

With the introduction of Senator Chuck Schumer's Cannabis Administration and Opportunity Act, Congress may finally end one of Uncle Sam's most controversial policies – the federal ban on marijuana and all its associated penalties. While Americans today are fully accustomed to the debate, few are aware of the history that spawned the movement for legal weed, beginning in the early 20th century when most drugs in America were completely legal.

Since marijuana became illegal in 1937, politicians, pundits, users, and everyone in between have debated the merits of the federal ban. Often, supporters have argued that marijuana is a dangerous drug, while opponents of the ban have cited everything from mass incarceration among the poor and minority groups to personal freedoms and the fiscal black hole that has become the War on Drugs. As Pew found in 2022, today, the tide is definitively on the side of legal weed as 53% of Americans – the vast majority of them under 70 – support overturning the federal ban. Here is how the United States got to this point and what may change should the Senate pass Schumer's bill.

The Wild West of drugs in early 20th century America

Before jumping into the specifics of marijuana, it is worth highlighting American drug policy before the bans of the early 20th century. Before then, many banned substances were unavailable or were not widely used. That changed first the introduction of opium, its derivatives heroin and morphine, and finally cocaine, marijuana, and amphetamines.

According to PBS, Americans have used drugs since the colonial era. In the 19th century, marijuana was widely available in pharmacies, and no one seriously questioned its medical utility. According to the Lancet, morphine (mostly used on the battlefield) and its cousin heroin were used as child cough suppressants. Medical societies even advertised heroin as a safer, less-addictive morphine alternative. Meanwhile, German doctors noticed that soldiers high on a white powdery drug derived from coca leaves suffered less fatigue. Soon, cocaine graced wine bottles and early Hollywood sets.

With the ubiquity of drugs, addiction rates skyrocketed, particularly among the urban poor and upper and middle-class women both in America and in Europe. In response, a handful of governments, per the Office of Justice Programs, entered into a compact to regulate the drug trade. In meeting its treaty obligations, Congress went beyond with the sweeping 1914 Harrison Narcotics Tax Act, which forbade unregistered parties from producing, importing, or distributing cocaine and certain opiates outside of medical purposes. But these were not drug bans. Those came later in the 1920s. Marijuana, which was not targeted under the legislation, soon found itself in Uncle Sam's crosshairs.

The ban drops

Marijuana, unlike cocaine, heroin, or amphetamines, had been known since Jamestown, the first successful English colony on the American continent. Per PBS, hemp, the plant from which marijuana is derived, was excellent for making sails, rope, and clothing. In the antebellum South, it was a plantation cash crop. Per OSU, an 1862 issue of Vanity Fair even encouraged recreational use for its relaxative and medicinal qualities.

So how did this drug become the target of stringent federal bans? There are two related versions of the story. One tells that the arrival of marijuana-smoking Mexican migrant laborers to the United States in the early 20th century led 26 states to criminalize the drug. William Randolph Hearst's newspaper empire regularly ran tragic stories of drug use (coinciding with Prohibition), to build public support while targeting Mexicans as culprits for bringing the practice to America.

The federal ban dropped in 1937. Now, according to the book "NAFTA and Neo-Colonialism," the ban had more to do with business than public health. Petrochemical giant DuPont had just patented the synthetic fabric nylon with considerable investment from men such as Treasury Secretary Andrew Mellon and Hearst. Hemp, the authors argue, provided a cheaper alternative to nylon, making the new fabric unprofitable from the get-go. So Hearst's media machine regaled the American public with stories of drugged-up foreigners (especially Mexicans) raping American women and destroying society. Regardless of the veracity of this story, the 1937 Marihuana Tax Act banned the drug's use recreationally (via DPA) without any exceptions for medicinal use.

The IND program

As the Drug Policy Alliance notes, the 1970 Controlled Substances Act placed marijuana as a Schedule I drug (the highest classification) despite previous medicinal use. But some, such as the famous Irvin Rosenfeld, swore that the drug kept them alive. According to Vice, the stock broker Rosenfeld was diagnosed with congenital cartilaginous exostosis, a painful bone disorder treated with high doses of painkillers – presumably addictive opiates.

In the ferment of the hippie-dominated college campuses of the 1970s, Rosenfeld discovered that he could control his pain with marijuana, claiming to be pain-free after ~10 joints. He linked up with another user named Robert Randall, who had controlled his glaucoma with home-grown marijuana. Randall and his wife were arrested in 1975 for growing hemp and promptly sued the US government on grounds of medical necessity. And they won in no small part thanks to this UCLA study, which confirmed marijuana's effectiveness in pain control.

In response, the FDA created its Compassionate IND Program for marijuana. Simply put, anyone demonstrating a medical need for marijuana could apply with a doctor's sponsorship for an exemption. Their experiences would be documented and serve as research while Uncle Sam sent members taxpayer-funded joints every year. Although the program only approved 13 applications before it ended, activists realized medicinal use was a sure-fire road towards legalization. Subsequent battles over marijuana took up this issue before recreational use came to the fore.

The medical route

As noted earlier, states had taken the lead in prohibiting marijuana use in the early 20th century. Now, they took the initiative to nullify the federal ban beginning with medical use. According to Britannica's Pro-Con, between 1979 and 1982, with mounting evidence for marijuana's effectiveness as a pain reliever, 24 states and Washington, D.C. legalized medicinal marijuana. Ten other states followed but either repealed them or, in the case of Maine and Michigan, let them expire.

States' legalization regimes took advantage of a loophole in the federal ban on marijuana. The 1970 Controlled Substances Act allowed doctors to use illicit substances in medical and scientific research with federal approval. So Alabama, for instance, allowed doctors to administer the drug for therapeutic purposes in the context of cancer and glaucoma research. States like Connecticut and Arizona allowed doctors to prescribe the drug, almost always for glaucoma and cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. Iowa tried downgrading marijuana to a Schedule II drug when used for medicinal purposes.

It is important to note that this did not amount to legalization. Recreational and most medical marijuana remained illegal at the federal and state levels. But the relaxation of some restrictions also exposed conflicts that could only end in either a total ban or medical legalization. It was and remains illegal for physicians to prescribe schedule I drugs, while patients back then could not legally buy marijuana even if it was prescribed. Thus began the movement to fully legalize medicinal – first through ballot initiatives and then through legislative action.

As goes California so goes the nation.

The LA Times cited this famous maxim in a 1989 piece, noting that the Golden State was a lab for progressive causes often resolved through popular ballot initiatives rather than in the state legislature. In 1996, it did not disappoint legal weed advocates when California became the first state in the country to enshrine medical marijuana in state law.

According to Ethan Nadelmann (above), founder of the Drug Policy Alliance (via NY Magazine), Proposition 215 came during fierce national debates over the War on Drugs. In the 1980s, the Reagan administration escalated the Drug War with increased penalties for possession and distribution as doctors frequently prescribed marijuana for terminally-ill AIDS patients. San Francisco had already passed Proposition P in 1991 for AIDS patients to obtain the drug. Prop 215 made legalization statewide.

According to Britannica's Pro-Con, Proposition 215 passed with 56% of the vote in what was an open nullification of federal law. Thus, according to Nadelmann, it caught the attention of the otherwise-liberal Clinton Administration, which had strengthened the Reagan commitment to the Drug War. Instead of respecting California's vote, the DEA would target doctors and dispensaries under the federal ban.

Ultimately, Bill Clinton was rowing against the current. As Pro-Con notes, seven states and D.C. followed California with effective medicinal legalization by 2000 (by then including oils, food, etc.). After the Supreme Court refused to hear government appeals to strike down medicinal marijuana laws, that was it. Uncle Sam would have to compromise with legal weed advocates – but it took another decade or so before doctors could prescribe risk-free.

Federal decriminalization for medical purposes

In the latter half of the 2000s, six more states (via Pro-Con) legalized medicinal marijuana either through ballot initiatives or legislative action. According to the 1996 LA Times, The Clinton Administration initially threatened to send the DEA after doctors and dispensers, arguing that medicinal use was a front for full-on legalization. Doctors called the restrictions "draconian," placing them in a "moral dilemma." Studies had already proven marijuana's medical value, and before 1914, few disagreed. Thus, could a doctor fulfill his oath if he refused medicinal marijuana rather than opiates to a terminally-ill patient under the threat of federal prison and loss of medical licensure? They argued no.

In 1996, the federal government had some support from lawmakers, including the California attorney general. But matters changed in 2009 with the election of Barack Obama and the Ogden Memo. The document reversed previous federal policy, noting that if physicians prescribed and dispensaries distributed marijuana in accordance with state laws, the DOJ would look the other way. However, in 2011, according to Reason, the Obama administration changed its tune and began raiding dispensaries – even if they were not involved in organized crime.

In the end, Congress stepped in to curb DEA activities. The 2015 Rohrabacher-Farr Amendment was slotted into that year's Senate Appropriations Bill. Although it did not stop the DEA from engaging in marijuana eradication programs, the amendment – which passed – stripped the agency of some of its anti-marijuana funding. No longer could the DEA use funds from states where medicinal marijuana was legal to target registered providers.

The battle for recreational pot

Today, medical marijuana is legal in most states, and the federal government has increasingly adopted a hands-off approach in the face of popular support. Recreational weed, however, was a separate battle that began in earnest in the '70s with the Shafer Commission. The commission noted that penalties under the 1970 Controlled Substances Act (one year for possession, five to 10 for distribution) were overly harsh. But according to the Nixon Tapes (via CSDP), the Nixon Administration was determined to crush the counterculture movement of the 1960s (particularly the Civil Rights and anti-war movements), with whom marijuana smoking had become heavily associated. Richard Nixon viewed the introduction of marijuana to American society as a plot to bring down the country and accused Jewish doctors of ramming it through.

Thus, the Nixon Administration ignored the commission's three recommendations. First, he refused to decriminalize the possession and distribution of small amounts for personal use, despite the commission's concession to keep public use illegal. Further, the feds refused to add a section to federal law that would have forbidden anyone committing crimes while high from using intoxication as a defense. Effectively, marijuana would have become similar to alcohol. Instead, it fell to the states to legalize recreational use.

Oregon wins the race

One might expect that California would have been the first to legalize it. California did try. Per Ballotpedia, Proposition 19 in 1972 would at least have decriminalized small amounts of marijuana for personal use, but it was crushed at the ballot box 67% to 33%. Instead, it fell to Oregon, which decriminalized possession and downgraded it to a civil violation, which still carried a fine, but spared the violator prison and a criminal record.

Now, the Connecticut General Assembly, as the state was facing its own debate on the issue, studied the effects of decriminalization in Oregon and the handful of other states that followed its lead. As seen in the CDSP report on the Nixon Tapes, there was a fear that decriminalization and legalization would see a larger amount of use, including among minors. Yet, in the 1970s, the number of new users and people arrested for possession and distribution skyrocketed. But as the CGA noted, the number of first-time users (and arrests) in Oregon actually fell following decriminalization from 21/1,000 in 1976 to 8.5/1,000 in 1990. So regardless of one's view of the issue, the case of marijuana in Oregon suggested that criminalization of the drug – at least of small-time users that per the Shafer Commission constituted the vast majority of American users – was not the way to go.

The right to privacy

While Oregon decriminalized through legislation, Alaska's Supreme Court was the vehicle for the Last Frontier's battle with marijuana, which took on a completely different character from other legalization efforts. The case in question was Ravin v. the State of Alaska. According to the Anchorage Daily News, lawyer Irwin Ravin and his law partner Robert Wagstaff enjoyed smoking marijuana after work and had worked to have the state's drug law overturned on privacy grounds. So they got themselves arrested for possession at a traffic stop and took their fight to the Alaska Supreme Court.

In the opinion authored by C.J. Jay Rabinowitz, the court found that Ravin did have some privacy protections. The court rejected the right to possess marijuana in public – particularly while driving. But citing Griswold v. Connecticut and Roe v. Wade, the court ruled that while Alaska could claim a compelling state interest in policing marijuana use among immature teenagers, mature adults were beyond the state's reach if they used it in the home. Thus, the case was remanded to a lower court, which was ordered to revise previous rulings against Ravin.

As a result of Ravin v. State, it became legal for Alaskans to possess up to four ounces of marijuana for personal use. But according to Ballotpedia, the 1990 Measure 2 re-criminalized all possession of marijuana and slapped offenders with a 90-day prison sentence.

Decriminalization

The 2000s and 2010s, per this Washington Post infographic, saw a host of states and municipalities decriminalize the drug. Using New York as an example, it is easy to see why decriminalizing the commonly-used drug was considered a common-sense move. The New York ACLU compiled a series of stories detailing the consequences of marijuana arrests – particularly for people with otherwise-clean criminal records. For instance, two college students arrested for possession (despite not using publicly) faced a lengthy court battle to have their records cleared. The 18-year-old Sea Loftin nearly faced job training, financial losses, and prison because of a joint that may not even have been his.

The New York State page illustrates the reasoning behind decriminalization. A criminal conviction for marijuana possession – even small personal amounts – shows up on criminal background checks that can affect future prospects for employment, housing, personal finance, and benefits. The Atlantic noted that although marijuana is used among rich and poor alike, the latter are often slapped with much tougher sentences. Thus, a teenage act of rebellion can become a barrier to future social mobility and a better life. While there are plenty of discussions to be had over personal responsibility, the statistics have suggested that locking people up is probably not the answer. Some advocates have even argued that decriminalization is not enough, and increasingly states have been moving towards legalization.

Legalization

Today, the major question rests upon the legalization of marijuana. The movement got its impetus in 2012, when both Washington State and Colorado, per CNN, legalized the drug in violation of federal bans. This news was significant, not just because it reversed nearly a century of federal policy toward the drug.

According to CNET, marijuana legalization in 2012 and beyond was quite disruptive. As of 2022, 19 states had legalized recreational use of the drug while 38 had legalized medicinal marijuana. The drug is increasingly popular, and celebrities use it openly, most famously Elon Musk (above). Medicinal marijuana was easier for the feds to ignore, since the users were mostly terminally-ill patients that otherwise would have suffered. Recreational use, however, was another story. While decriminalization was often local authorities looking the other way on marijuana possession, legalization was a direct nullification of federal bans on marijuana.

Legal experts noted that marijuana legalization at the state-level "[bred] confusion and uncertainty" on several fronts, necessitating the re-evaluation of federal policies that have placed marijuana as a Schedule I drug. In 2022, legal weed advocates got just that when Congress introduced a bill to lift the federal ban and its associated penalties.

The two sides today

With the introduction of Chuck Schumer's Cannabis Administration and Opportunity Act, Americans are divided over legalization mostly along generational lines. According to Pew, 40% of Republicans and ~60% of independents and Democrats favor legalization – a larger portion in the former category than one might suspect. When polled intergenerationally, however, Pew revealed a gap between Baby Boomers, Gen X, and Millennials on one hand (50-70% support) and the "Silent Generation" (29% support), which opposed legalization over marijuana's perceived danger to society and its addictiveness.

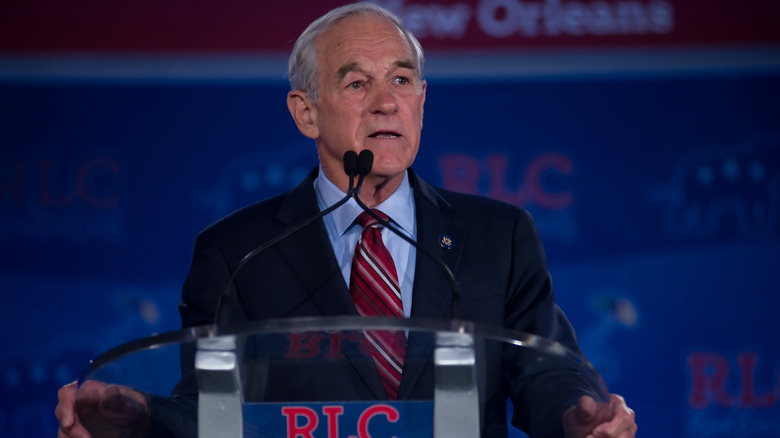

So what are the arguments for legalization? In an interview with the cannabis magazine High Times, former Republican Congressman Ron Paul argued that legalization is best from a policy and personal freedom perspective. Per Paul, the Drug War perpetuated cartel violence over the profitable American drug market criminalization created – similar to bootlegging and Prohibition. As Paul sees it, marijuana legalization through state-level nullification of federal law is a pro-freedom compromise that would balance the interests of users and society.

Paul argues that legal marijuana will result in a more socially-responsible society if accompanied by proper regulation. Americans have the right to use marijuana, he believes, but must accept any consequences – particularly if it leads to crime. But compare Paul's argument to alcohol. It is legal until one gets behind the wheel and then gets into a DUI accident. The driver goes to jail, but few will call for prohibition in response to DUIs. Paul is effectively arguing the same for marijuana. There just needs to be the will on the Feds' part to "butt out."