The Untold Truth Of The Glorious Revolution

The Glorious Revolution was one of the most important events in modern English history, when the unpopular King James II was replaced on the British throne by William of Orange and his wife Mary. The trouble started in 1685, when the openly Catholic James II ascended to the throne of England upon the death of his brother, Charles II. His public Roman Catholicism alienated James II from the majority of Englanders and Parliament, and in 1687, he decreed the first "Declarations of Indulgence" — which essentially legalized Catholicism in England. This drove an even bigger wedge between James II and Parliament, and he dissolved it in the effort to create one more favorable (per History).

In the midst of the bickering between James II and Parliament, the Dutch leader William of Orange, a Protestant, invaded England on the southern coast at Torbay and started pushing north. In response, King James II fled from England to France to the security of his cousin King Louis XIV, where he remained for the next 13 years until his death. Meanwhile, William of Orange and his wife Mary became the new king and queen of England, Scotland, and Ireland.

Though the revolution happened over three centuries ago and is taught in schools every year, there is still a lot many people do not know about it. This is the untold truth of the Glorious Revolution.

Parliament tried to prevent James II from becoming king

Even before he became the king, Parliament had already been wary of James II for years. It had less to do with him as an individual and everything to do with his affiliation with the Catholic Church. The Catholic Church had a violent history in England, and many feared there were vast Catholic conspiracies afoot. These conspiracies were based, in part, on events like the Gunpowder Plot of 1605, when Guy Fawkes and 12 other militant Catholics tried to kill King James I and replace the monarchy with a Catholic government (per History).

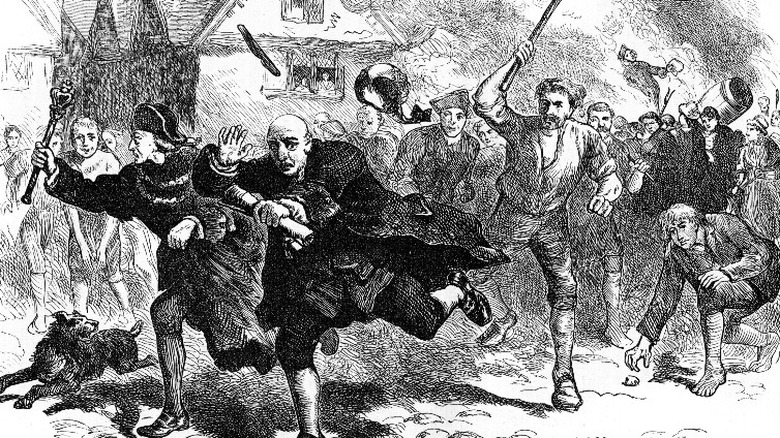

In the 1670s, the people of England first learned that James II, the next in line for the throne, had become a Catholic, and new conspiracies quickly popped up (via History Extra). One of these was planted by a former Catholic, Titus Oates, who alleged that there was a new secret plot underway to kill the current king, Charles II, and replace him with the Catholic James II. The new conspiracy gained teeth when a magistrate was found murdered, and soon, Catholics from around England were the target of violence.

Fearing the possible ascension of James II to the crown, Parliament attempted to pass legislation that would have prohibited him from ever taking the throne. Yet, in 1681, Charles II dissolved Parliament and prevented any new laws from being passed. Had Parliament successfully prevented James II from becoming king, the entire Glorious Revolution would never have happened.

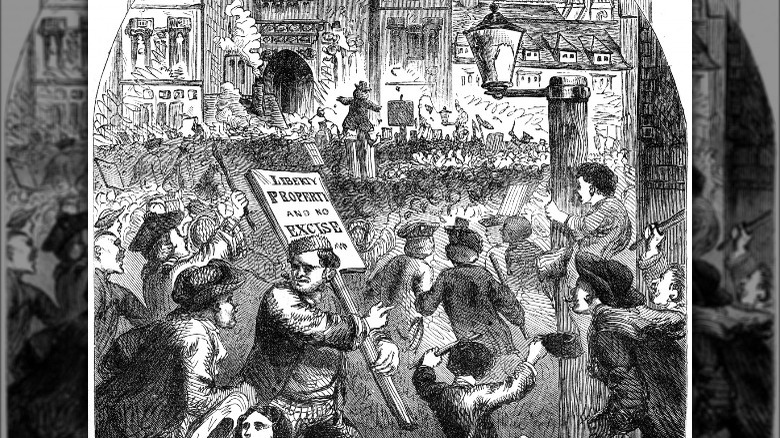

It caused a revolt in Boston

Most people think that the effects of the Glorious Revolution were limited to England, but that is far from correct. The ripples of the revolution spread quickly to several places, including England's colonies in the New World. According to the New England Historical Society, Massachusetts was one of the first colonies who responded to the outcome of the Glorious Revolution.

The problems had started in Boston a few years earlier during the previous reign of King Charles II. He was upset with the New England colonists for not thoroughly recognizing the crown's authority over them and acting with too much independence. In 1686, his successor James II, still upset at their lack of respect, installed a new governor — Sir Edmund Andros. Andros immediately ran afoul of the Puritans in Boston when he started to advocate for the Church of England's recognition and hold unauthorized Anglican services.

After two and a half tense years, word reached Boston that James II had been deposed during the Glorious Revolution, and Andros' time was up. Colonists from throughout the Massachusetts colony revolted against his rule. They came together to form a militia, and they confronted Andros, arrested him, and threw him in prison. He was released a year later and returned to England, by which time the Massachusetts colony had elected their own governor to replace him.

People in New York also revolted because of the Glorious Revolution

Massachusetts was not the only colony to take advantage of the outcome of the Glorious Revolution. Hearing about the events in Boston, the colonists in New York also decided to rebel against their crown-imposed authority (via Michael G. Kammen in "Colonial New York").

In May 1689, the New York militia overthrew the lieutenant governor of New York, and a few months later Jacob Leisler became the colony's new commander in chief. He soon called for a new government, and in the spring of 1690 the New York Assembly met for the first time.

However, back in England, King William had installed a new governor for the New York colony in March of 1690. It took the newly appointed governor 14 months to finally make it over from England, but when he arrived, Leisler refused to cede authority. Leisler was quickly arrested, tried, and convicted, and then sentenced with a co-conspirator to be hanged "by the Neck and being Alive their bodys be Cutt downe to the Earth and Their Bowells be taken out and they being Alive, burnt before their faces; that their heads shall be struck off and their Bodys Cutt in four parts.'" He was executed on May 16, 1691, finally bringing "Leisler's Rebellion" to a nasty end after two long years.

It was not a bloodless revolution

The Glorious Revolution is often referred to as the bloodless revolution, but in reality there was actually quite a bit of death throughout England, Scotland, and Ireland. After William of Orange landed on the southern coast of England at Torbay in November 1688, James II refused to engage him with the royal army (via History Extra). In fact, there were not any major battles between James II's army and the invading Dutch army under William, which is what initially gave rise to the terms "glorious" and "bloodless" revolution (per Lynn Hunt in "The Making of the West: People and Cultures").

However, there was still bloodshed, and lots of it. A member of Parliament, Lord Lovelace, was captured and two of his men were killed in battle after they tried to link up with William's invading army. In December, there was a small skirmish between William's scouts and another Irish royalist force, which ended with over 50 dead.

The Glorious Revolution also caused instability in both Scotland and Ireland, as both places refused to accept the revolution and crowning of William and Mary. At the "Battle of the Boyne," 1,500 soldiers died in a battle for the recognition of William's authority in Ireland. In one particularly gruesome incident in Scotland, known as the "Glencoe Massacre," William ordered his troops to kill all of the men under 70 years old who were residing in a rebel outpost, killing dozens of Scottish men who refused to recognize his authority. Hardly a bloodless revolution.

William of Orange was actually King James II's son-in-law

As hard as it is to believe, the man who eventually overthrew King James II, William of Orange, was actually the king's son-in-law and nephew. Per Historic U.K., William was born in November 1650, in The Hague, Netherlands. His father was William II, Prince of Orange, and his mother was Mary Stuart of Orange, and she was also the daughter of King Charles I of England. King Charles had two other children, both of whom eventually succeeded him as king: Charles II and James II (via Historic U.K.). This made Mary Stuart's son, William, the nephew of James II — because James II was her brother.

During Charles II's reign, he knew that his brother James II's Catholic leanings were unpopular with Parliament. So, he helped arrange for James II's daughter, also named Mary and who was Protestant, to marry William, consolidating Protestantism within the Stuart royal line.

This made William not only James II nephew, by birth, but also his son-in-law through his marriage to James II's daughter, Mary. William wound up deposing his father-in-law during the Glorious Revolution. As a result, James II fled to France, avoiding what would have been the world's most awkward family reunion.

The English asked to be invaded

It might sound surprising and be a bit hard to believe at first, but the English actually asked to be invaded by a foreign country during the Glorious Revolution. King James II took power in 1685, and he quickly ran into problems with Parliament. He had it dissolved twice, both times over criticism of his overt Catholicism (via BBC).

Many peers were already worried that James II's third Parliament would make some of his pro-Catholic policies permanent, and the final straw for them was the birth of his son, which sealed a Catholic heir for the future royal line of succession.

To save the royal line from remaining Catholic, seven British peers wrote to William of Orange, the Dutch Protestant leader, and announced their allegiance to him if he invaded and deposed King James II. William was already planning on invading England, because he wanted them to join his war against France, and he knew James would not allow this because he was the King of France's cousin (via History). William used the peers' invitation as propaganda for his successful invasion, where he deposed King James II and took over his throne. William, a Dutchman, then sat on the English throne for the next 13 years.

It established the first Bill of Rights

One of the most important, and not often recognized, legacies of the Glorious Revolution is that it is responsible for creating the first Bill of Rights (per History). British Parliament had existed since the early 13th century, when it was established by the Magna Carta, and over the next four and a half centuries its powers ebbed and flowed (via History). It actually abolished the monarchy at one point, in 1649, in the midst of the English Civil War, before restoring it to power under Charles II in the English Restoration.

Yet, it was not until the Glorious Revolution that Parliament really started to gain teeth and become an effective independent body. As part of the conditions of William and Mary becoming the new king and queen of England, they agreed to sign the English Bill of Rights, which limited the power of the monarchy and strengthened the independence of Parliament (via History). It mandated freedom of speech in Parliament, and prohibited the king or queen from interfering with Parliamentary elections or with the English legal system. It also prohibited Catholics from taking the throne, which was really what the entire revolution was about in the first place.

The English Declaration of Rights, as it was known, inspired the creation of governments around the world. The United States' Bill of Rights is a direct outgrowth of the Declaration, and many other countries also utilize a similar Bill of Rights in their constitutions.

King James II was not unpopular when he first came to power

Contrary to popular belief, James II, though he was a known Catholic, was actually relatively supported when he first became king in February 1685. The first Parliament he presided over was known as the "Loyal Parliament," and James II appeared ready and willing to work with them and move past their deep-set differences (via Historic U.K.). Parliament at first seemed also willing to work with him, and actually gave him a pretty hefty salary as the king.

He promised to maintain the current government and church, and stressed that his Catholicism would not be an issue (via BBC). Parliament gave him emergency money to fend off an internal rebellion from his illegitimate nephew, and his soldiers stayed loyal to him during the battle.

James II started to run into problems when he began to rearrange the army to promote Catholic officers, and by the end of November he had already dissolved Parliament for the first time. It was mostly downhill from there for James II and his popularity, but for almost the first year of his reign he did have support.

William of Orange allowed King James II to leave

It is not often that an invading king of a different nationality is welcomed with open arms, but that was exactly the case during the Glorious Revolution. King James II's Catholicism was too unpopular in England, and he quickly wore out his welcome as monarch. In November 1688, when William of Orange invaded England, he seemed to have more support than James II did in his own country. Not only did Protestants in the countryside welcome William and his army as they progressed north toward London, but several of James II's own family members even fled from his side to William's (via History Extra).

The few members of his family who did remain loyal, like his wife Queen Mary and his son the Prince of Wales, fled from England to France in December after seeing the writing on the wall. James II tried to join them and schemed to prevent Parliament from being called in his absence, but fishermen caught him and brought him back. William wanted nothing to do with James II and ordered his guards to allow him to "slip through" their defenses and escape. James II was then able to make it to France, and to the safety of his cousin Louis XIV and the comfort of his wife and son, where he eventually died in 1701 (via Historic U.K.).

The Glorious Revolution increased the slave trade in England

One of the most surprising legacies of the Glorious Revolution is it increased the slave trade in England. In the mid-17th century, King Charles II had decided to grant a monopoly on the West African slave trade to the Company of Royal Adventurers Trading to Africa, who eventually became the Royal African Company (RAC) (via History). The RAC controlled the English slave trade along nearly 5,000 miles of West African coastline, taking an average of 5,000 slaves per year to the New World.

However, the Glorious Revolution dealt the RAC a series of crushing blows. Per historian William A. Pettigrew, the company lost its ability to forcefully exert its monopoly when James II fled England upon William of Orange's invasion. Then, in 1698, without a sympathetic king to back them, Parliament removed their monopoly for a temporary period of 13 years — opening up the slave trade to private traders. In 1712, the RAC's lack of monarchical support again cost them their monopoly, as the slave trade was permanently opened to private slavers in England. The opening of the West African slave trade to private traders caused it to massively increase, with English ships eventually transporting an average of 20,000 enslaved people per year — four times as many as the RAC averaged in their heyday (via PBS). Without the Glorious Revolution, the RAC would probably have held their monopoly much longer, prolonging the privatization and expansion of the slave trade for decades.

King James II was almost never the king

The basic story of the Glorious Revolution is pretty well-known; the English Parliament, upset at James II's overt Catholicism, rebelled against him and accepted the rule of William of Orange and his wife Mary in 1689. However, what most people do not realize, is just how close James II came to never being the king at all.

Legally, his brother Charles II was married to Catherine of Braganza, the daughter of the King of Portugal. However, she did not speak English and Charles II did not speak Portuguese, so communication between them was limited (via Royal Museums Greenwich). What's more, Charles II was having an affair with Barbara Villiers — who was also married — and he did so openly, with no regard or respect for his wife Catherine.

He ended up having a total of 13 children, with seven different women — none of them from his wife Catherine (via History Extra). Yet, if Catherine had been the mother of any of these children, James II never would have been in line for the throne, and the Glorious Revolution would never have occurred.

The Glorious Revolution was the last successful invasion of England

One of the biggest military advantages that Great Britain and Ireland have always had is their separation from mainland Europe. Being an island country off the coast, they have been isolated from much of the upheaval and turmoil that occurred on the mainland throughout history. WWI and WWII are the most recent examples of this, as in both wars, England remained uninvaded and did not suffer nearly the destruction of mainland countries like France, Belgium, and Germany.

However, it is not completely impermeable to penetration, and the Glorious Revolution is actually the most recent time that England has been invaded by a foreign country (per History Extra). Many people think that William the Conqueror's Norman invasion in the 11th century was the only time it has successfully happened, but William of Orange's landing at Torbay in 1688, though relatively uncontested, was still a military invasion and campaign. There were several British peers who welcomed the invasion, but it was still a foreign invasion nonetheless.

Parliament struggled with commemorating the revolution's 300th anniversary

Even though the Glorious Revolution happened in the late 17th century, the people of the United Kingdom are still struggling with how to commemorate it. Part of it has to do with the public image of William of Orange in England. Many people in England highly revere William and consider him the "Good King" and a "sympathetic figure," who was loyal, a patron of the arts, and respected the wishes of Parliament (via History Extra).

However, the United Kingdom consists of not just Great Britain, but also Ireland, and William's reputation there is much less favorable. He is known as "King Billy," and many Irish see him as akin to a ruthless tyrant who brutally oppressed the Irish and massacred them at the Battle of the Boyne.

In 1988, on the 300th anniversary of the beginning of the Glorious Revolution, there was also tension in Parliament about how William's ascension should be commemorated. Some members wanted to celebrate the invasion as a "peaceful transfer of power," but others pointed out the gross inadequacies that really existed at the time of the revolution. MP Tony Benn argued that the revolution was representative of mainly rich, white, Protestant males, and had no considerations for the middle or working classes, or women.

Parliament did end up celebrating the 300th anniversary and William himself, with great fanfare and pomp, and it featured a speech by the Queen (via the Associated Press).

It influenced the creation of William and Mary College

William and Mary College, one of the most prestigious collegiate institutions in the country, owes a lot of its history to the Glorious Revolution. According to historian Homer J. Webster, William and Mary was one of the first three "colonial colleges" to be established in what would become America. (Harvard and Yale were the other two.) All of them were "founded, governed and supported mainly by church influences," and the curriculum was focused around training future ministers.

In 1660, the Virginia Assembly asked for the funds to create a new college, but it was not until 1693 that a charter was finally signed. By this point, William and Mary were secure on the throne of England, and they created the college in their namesake to be a "perpetual College of Divinity, Philosophy, Languages, and other good Arts and Sciences" (per the Virginia Museum of History and Culture).

The new college was to uphold all of the traditions of the Church of England, and all governors and even visitors had to be members of the Church, too. If James II had still been the King of England, he never would have allowed the creation of a new college loyal to the Anglican Church — because James II was a Catholic. Without William and Mary coming to power, their namesake college might never have existed, or if it did, it would have likely been in a radically different form.