The Untold Truth Of China's Forbidden City

There's something universally attractive about "forbidden" things, whether it's the cake your mom told you not to sample or an entire city full of ancient artifacts, mysterious artwork, and cats. China's "Forbidden City" is no longer technically forbidden — in fact it welcomes millions of tourists annually, so it would really be more accurate to call it the "Allowed City," or maybe the "Permitted City." No one would go there, though, because things that are allowed and permitted are totally boring. But the Forbidden City's forbidden past is fascinating enough, even without the label.

The Forbidden City is not an actual city

The Forbidden City is a palace, not a city. It was built to be the home for one man, or to be precise, one intact man. According to Live Science, the Forbidden City's thousands of rooms and hundreds of buildings were the exclusive residence of the Chinese Emperor, and no one else who possessed, shall we say, a complete set of male equipment was permitted to enter, with the exception of the Emperor's immediate family. Hence the name "forbidden."

The palace was commissioned by Zhu Di (also known as the Yongle Emperor) in 1402, shortly after he gave his royal nephew the royal get-the-eff-out-of-here. Zhu Di wanted to rule from his own power base in Beijing, which was probably smart given that there were people in the old capital who were annoyed at him for overthrowing his nephew. Over the next 600 years, 24 different emperors belonging to two dynasties would occupy the Forbidden City, right up until the ousting of 5-year-old emperor Puyi in 1911. Today the Forbidden City is a museum, housing more than 1.5 million artifacts. And don't worry, no 5-year-olds were harmed in the making of this museum — Puyi went on to become emperor of the Japanese puppet state of Manchukuo, which was kind of lame compared to being emperor of the entire nation of China, but at least significantly better than death.

The complete translation of the name is 'Purple Forbidden City'

The name "Forbidden City" is translated from "Zijin Chen," which actually means "Purple Forbidden City." Before you go squinting at palace photos and wondering if you're missing something, the name doesn't have anything to do with the literal color of the palace. According to Asia Times, the color was a reference to the North Star, which the Chinese associated with the color purple. The North Star had religious significance — the Son of Heaven lived there, and the emperor was the Son of Heaven's counterpart on Earth, so, logic.

The rooms inside the Forbidden City have colorful names, too, like "The Hall of Supreme Harmony," "The Hall of Complete Harmony," and "The Hall of Preserving Harmony." It's kind of hard to say what the difference is between Supreme, Complete, and Preserving Harmony, but clearly the emperors knew something the rest of us didn't.

The Forbidden City as a whole has a few other much less seductive names, too. It's official name is "The Palace Museum." And the locals call it Gugong, which literally means "The Former Palace." Like "Allowed City" and "Permitted City," it's doubtful that particular name will ever end up in a color brochure.

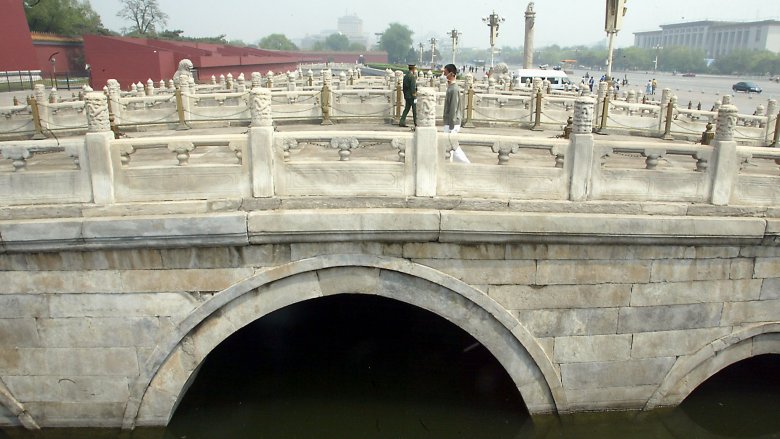

It took 14 years and a million laborers to build the palace

Workers labored for 14 years, which is really not a whole lot of time when you consider how many different buildings and rooms the Forbidden City actually has. What's remarkable is not just how many people were involved (it's said there were more than a million laborers) but what kind of effort it took just to get the building materials from point A to point B.

According to Scientific American, some of the stone blocks weighed more than 100 tons, and they had to be brought in from a quarry that was 43 miles from the building site. In those days, heavy materials were usually moved by cart, but surprise, there was no such thing as a wheeled cart that could move a 100-ton stone block. Instead, workers had to drag the stones by hand, and they did it in deep winter — not because of some crazily unrealistic royal building schedule but because it was actually more practical. Every few miles, workers dug a well and then used the water to create an icy surface on the road. That made the blocks easier to move — think ice skating for 20,000 pound Olympiads.

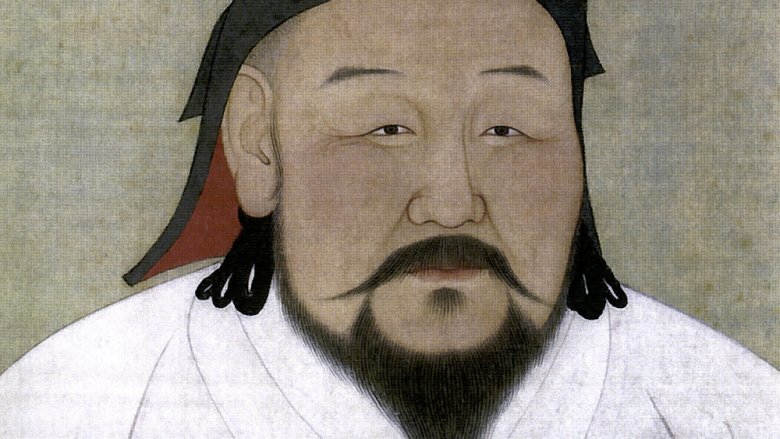

The Forbidden City was built on top of another famous palace

Between 1271 and 1368, China was ruled by the Mongols. Kublai Khan, who was the fifth emperor of the Yuan dynasty and the grandson of legendary bad boy Genghis Khan, built a large, gilded palace in Beijing, the future home of the Forbidden City. The palace was so magnificent that historians made note of it, but after the Yuan dynasty ended the entire thing vanished. Like Amelia Earhart, only it was an entire palace and it wasn't outside of radio communication somewhere over the Pacific Ocean, it was in freaking Beijing.

The disappearance of Kublai Khan's palace was one of those great archaeological mysteries, up until May 2016. According to the South China Morning Post, that's when archaeologists figured out why no one had ever found evidence of the old palace — because Zhu Di built the Forbidden City right on top of it. Archaeologists excavating near the center of the palace unearthed the seven-century-old foundations of another royal palace, evidence that something just as grand as the Forbidden City had once existed on the same site.

Perhaps the old magnificent palace wasn't magnificent enough for Zhu Di, or maybe he was trying to erase the legacy of the old dynasty. Or maybe it was just that ancient rule of real estate: location, location, location.

Ming emperors had a bunch of concubines

Ming emperors were pretty good leaders, but they could also be total jerks.

According to Ancient Origins, the emperor was known to keep up to 9,000 concubines in the Forbidden City, which at least partially explains why one guy would need so many rooms in his house. Think about that for a moment — if he called a different concubine to his bed every night, it would take him more than 24 years to cycle through the whole lot. As it was, most of his concubines never got called at all, but that didn't mean they were free to do other things. They mostly had to sit around and wait for their turn, even if it never came, and "sit" is a literal term here because many royal concubines could not walk. Their feet were so grotesquely deformed from the practice of foot binding that when the emperor wanted one of them, she had to be carried to his chambers. Also, she was carried naked, not just because it was sexy but because a naked woman couldn't smuggle in a concealed weapon.

Depending on the emperor, concubines were sometimes tortured, sometimes executed, and sometimes starved to death because there were so many dang concubines that there wasn't enough food to go around. And as a final reward for a job well done, when the emperor died they got to be hung from silk nooses at his funeral. Only the best for the emperor's ladies.

Concubines were often stolen from their families

So how exactly does one guy obtain thousands of sex slaves? Well, he's the emperor, so all he has to do is close his eyes and wish really hard, and imply that people might die if he doesn't get his way.

It was dangerous to be beautiful in ancient China. According to Precious Media, beautiful women were often stolen from their families to serve as the emperor's concubines — sometimes they were even offered by their families in exchange for political favor. Now, since concubines weren't actually allowed to write home or anything, all that stuff about torture, execution, and starvation probably wasn't common knowledge, so maybe families deluded themselves into believing that life at the palace would be better for their daughters than life at home.

The emperor's concubines lived in isolation from the outside world — they weren't even permitted to see a doctor if they got sick. Instead, they were diagnosed based on a written description of their symptoms, sort of like WebMD only with actual doctors.

Not every concubine had to die with the emperor, though. That honor was reserved for favorite concubines, which means it was one of history's few professions where getting promoted was not something you celebrated with champagne and a night on the town. For regular, non-favorite concubines, it was possible to "retire" after serving a few years, and then go on to an auspicious career as a laundress or a nun, which were really your only other options.

Dudes couldn't enter the city with all their body parts

By the end of the Ming Dynasty there were 70,000 eunuchs living in the palace. That's right, men, if you ever visit the Forbidden City, you should cross your legs and give thanks to the North Star that it's not 500 years ago and you can walk out again with your junk still attached.

According to Wonders and Marvels, eunuchs were the only non-emperor men who could live in the Forbidden City, mostly because the emperors feared what would happen if intact men spent too much time hanging around with 9,000 concubines. But the really unbelievable thing about Chinese eunuchs is that it was a volunteer workforce. Life outside the palace was so bad, apparently, that healthy men would volunteer to be parted from their bits and pieces (yes, the family jewels and the family scepter, as it were) in exchange for a life of luxury. Mercifully, volunteers were given three chances to back out before the surgeon shucked the oysters — if the eunuch-in-training showed any sign of doubt, the surgeon would not proceed.

Ultimately it would all work out, though, because according to The Telegraph, the Chinese also believed if you were reunited with said body parts at death, you would be whole again in the afterlife. That's why eunuchs often carried their severed parts around in a little bag, just in case. Oh and also if you lost your parts, you could rent or buy a set from someone else. Seriously.

The Forbidden City burned down at least 50 times

There was a lot of wood in the Forbidden City. And also, no fire extinguishers. And also no firemen, because of the whole must-be-a-eunuch and oh-my-god-stay-away-from-my-concubines thing. Fire in the Forbidden City was a constant fear, and the palace burned more than 50 times over the centuries, including once within the first year of construction. To prepare for what was really an inevitability, bronze vats full of water were strategically positioned all over the palace, and there were even heating elements built into the floor to stop the water from freezing on cold days. In the event of fire, it was left to the eunuchs to save the palace.

According to China Radio International, when fire broke out in the early 1900s, firefighters arrived to combat the blaze, but the emperor could not be found and the gate guards were all, "We're not sure if we're supposed to let you in." Then an hour and a half later when someone did finally locate the emperor, he decided that he couldn't really decide whether to let the firemen in unless he called an emergency meeting, and by the time meeting attendees begrudgingly concluded that firefighters might be a good idea, the once picturesque Jianfu Garden had almost completely burned down. But as far as we know, no emergency responders had fiery liaisons with concubines as the city burned down around them, so that was good. Probably.

The Forbidden City was every little kid's dream house

Just about every child dreams of moving into a house full of secret rooms and hidden tunnels, though becoming a eunuch in order to actually do it probably doesn't figure into many of those fantasies. It probably wouldn't have been a whole lot of fun, anyway. According to the Asia Times, the Forbidden City's tunnels and secret rooms weren't there for hide-and-seek, they were there because the emperor was uber-ultra-paranoid and was always pretty sure someone was coming to kill him.

According to Live Science, security measures also included a moat that was 171 feet across and walls that were 32 feet high. Security was so tight that even the food was regulated — not only was a eunuch charged with tasting every meal so that he'd be the one to turn purple and ghastly like Joffrey, but it had to be done with a pair of silver chopsticks. Silver was said to immediately tarnish in the presence of poison, which is totally not true, though it seems it never actually occurred to anyone to test that particular theory. The silver-as-poison-detector myth persisted for centuries, and probably never did much except give that poor eunuch food-taster a false sense of security.

The ancient Chinese were into the number 9

People will still tell you that there are 9,999 rooms in the Forbidden City, and 999 buildings. That's probably not accurate, though it doesn't seem like anyone has ever bothered to count, or, more likely, it seems as if whoever was charged with counting died of boredom when they got to around 6,092 rooms. Ancient Origins puts the number of buildings at around 800, with something like 8,700 rooms.

The legend of 9,999 rooms in 999 buildings is just based on oral tradition, and probably comes from the Chinese belief that the number nine is correlated with longevity. For emperors who were constantly worrying about fire, vengeful concubines, and eunuchs who suddenly realize that their junk probably won't magically reattach when they die and who cares because they'll be dead anyway, filling the palace with multiples of nine probably gave them at least some small sense of comfort.

The number nine appears elsewhere in the palace, too. For example, according to Smithsonian Magazine, palace doors each possess nine rows of nine nobs. And also, the palace gets roughly 9 million visitors annually. Coincidence? Yep, it's totally a coincidence.

200 cats live in the Forbidden City

There is no longer a Chinese emperor occupying the Forbidden City, but the descendants of those who once lived with emperors still roam the palace grounds. China Daily reports that the Forbidden City is home to around 200 cats, and they aren't mere strays — they are practitioners of the cat's most noble and ancient occupation: rodent control.

The Forbidden City's feline employees actually have it pretty good. Not only do they get to live in the royal palace, but they're also cared for by museum curators. Palace cats are vaccinated, receive vitamins and other necessary supplements, and are allowed indoors in cold weather. Some of the cats living in the Forbidden City are strays who got lucky, while others were abandoned by owners who hoped someone at the museum would care for them. According to the BBC, still others are thought to be direct descendants of royal pets, although that royal pedigree probably ends with this generation, since all palace cats are now spayed and neutered. That's right, the male cats living in the palace are all technically eunuchs. Hooray for tradition.

Even commoners can eat imperial food now

Chinese emperors lived in pretty ridiculous opulence, from the clothes they wore to the food they ate. Emperors living within the Forbidden City didn't eat just any food, they ate "Imperial cuisine." According to Voice of America, Chinese imperial cuisine was forbidden to anyone who was not royalty.

During the Ming Dynasty, imperial dishes were often elaborate and difficult to prepare, and had names like "stir-fried sheep tripe," "cold sliced sheep tail," "deep-fried sparrows," and "intestine in intestine." Yum.

Today, even commoners can eat imperial food — although you do have to be a commoner with some significant cash in your pocket. A restaurant near the palace called Family Li Imperial Cuisine serves traditional imperial food. And the recipes aren't just a loose facsimile of real imperial cuisine. The restaurant's owner is the grandson of Li Zijia, who was actually in charge of the royal meals during the reign of Empress Dowager Cixi, and the food you'll eat at his restaurant is bona-fide imperial cuisine — the same recipes once served at the palace.

According to QLI Travel, dining at Family Li Imperial Cuisine is not inexpensive. Dinner might cost as much as $250 per person. And the restaurant only serves 10 people a day, so book ahead.

Starbucks is so not imperial food

If you've ever complained that Starbucks is infiltrating every corner of the known universe, take heart. America's favorite coffee shop was recently kicked out of the Forbidden City, sort of like a guy with both his avocados. Evidently, the locals were upset that the coffee giant was messing with palace ambiance.

In 2007, The New York Times reported that protests convinced museum officials that Starbucks' presence was "damaging" to the historical site, though it's unclear if they were annoyed about the coffee or if it was really just the smug coffee-drinking American tourists that bothered them. At any rate, Starbucks closed its doors shortly afterward. It's worth noting, though, that there are plenty of other palace-branded shops operating inside the walls of the Forbidden City, where you can get iPhone cases, "imperial mouse pads," or a set of headphones that looks exactly like the string of pearls some emperor guy is wearing in one of the Forbidden City's portraits. But Starbucks is too lowbrow. Perhaps if they'd changed their menu. Tripe-spiced latte and intestine in espresso, anyone?