What Americans Might Not Know About Jimmy Carter

There's a common thread running through assessments of 39th U.S. president Jimmy Carter: that he has been much more successful as an ex-president (via NPR). After four years of economic woes, unrest abroad, and unhappy relations with Congress and the press, Carter left office with a 34% approval rating and the ignominious distinction of being the only Democratic president since the 19th century not elected to a second term. His influence on politics and policy within the Democratic Party since his 1980 defeat has been minimal. By contrast, his post-presidency activities through the Carter Center and Habitat for Humanity has achieved widespread acclaim and, according to CNN, altered expectations of presidents after their time in the White House has ended.

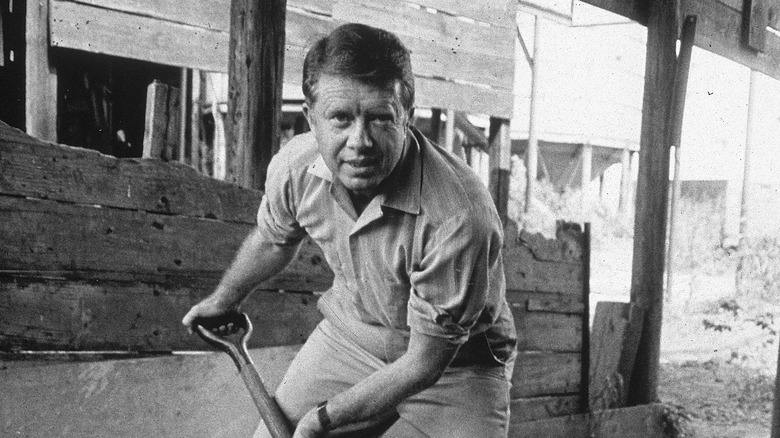

Some historians have worked to rehabilitate Carter's presidency (per PBS), though others have insisted the criticisms he's received are well-deserved (per Bloomberg). But the narrow focus on Carter's roles as president and former president tends to leave the rest of his political career unexamined. And the public image of Carter as an honest peanut farmer-turned-statesman who builds homes for the homeless and teaches Sunday school ignores the many contradictions and complications that he has in common with all of us.

His father was a segregationist

Writing for The Nation, author Rick Perlstein speculates on the role of upbringing in driving those who seek the presidency. Jimmy Carter, like many presidents of the modern age, had a distant father figure who set high expectations in his son and a nurturing mother who encouraged ambition and self-confidence. But Carter's parents pushed and pulled their son in another way — between wildly different perspectives on race. Earl Carter was an admired figure in the town of Plains, Georgia, but according to PBS, he was a committed segregationist. By contrast, Lillian Carter completely disregarded the social norms that enforced segregation, freely associating and often aiding her Black neighbors.

PBS quoted Carter's own description of his father as "the center of my life and the focus of my admiration," while noting his mother's example vis a vis race offered a glimpse of the potential within the New South ideas. The influence of both his parents and the insights they offered into different perspectives in the South emerged early in Carter's political career. Per the UVA Miller Center, he won endorsements from prominent segregationists in Georgia for his 1970 gubernatorial run and worked to garner support among segregationist voters. But he surprised supporters and opponents alike when he spoke out against segregation in his inaugural address after a narrow win, and he later substantially increased the presence of African Americans in Georgia's government.

He studied nuclear energy

According to PBS, Jimmy Carter's admiration of his father did not initially extend as far as wanting to keep up with the family farm. Instead, Carter followed his uncle's example and joined the U.S. Navy. He entered the Naval Academy in the midst of World War II and began service in 1946 (per the Jimmy Carter Presidential Library & Museum). By 1952, he reached the rank of lieutenant and obtained a reputation among his shipmates as a dedicated officer — friendly but distant and sedulous.

Carter's career trajectory seemed to aim at the goal of one day commanding his own submarine, but the prospect of waiting an unknown number of years for such a position was a boring one. Instead, according to Peter G. Bourne's "Jimmy Carter," the young officer applied for the Navy's new nuclear program. It was a change that required courses in nuclear physics through Union College and simulated the dismantlement of a nuclear reactor, which set the stage for the real thing after a meltdown in Chalk River, Canada.

By the time his training was completed, Carter seemed poised to become the engineering officer aboard the USS Seawolf, only the second nuclear submarine to have been added to the American fleet. But Carter's naval career was cut short by the death of his father, Earl, to pancreatic cancer on July 22, 1953 (per Julian E. Zelizer's "Jimmy Carter"). With his mother reeling from the loss and his brother Billy ill-suited to manage affairs, Carter ended his service to return to Georgia.

He once used public housing

When Jimmy Carter returned to Georgia in 1953 after his father Earl's death, he was immediately beset by problems. Earl had been a moderately wealthy man whose farm and businesses were significant providers to the community (per Peter G. Bourne's "Jimmy Carter"). When he died, he forgave most of the debts owed to him, but the town of Plains was still without means in his absence. Carter's mother recognized her inability to manage things alone and was desperate for him to come home; on the other hand, Carter's wife Rosalynn was happy with their life in the Navy and didn't want to return to the South.

To make matters worse, the following year saw Georgia stricken with a severe drought that badly damaged the Carter peanut farm (via UVA Miller Center). Its net profit for 1954 was only $187. With business bad and Carter's naval pay having been low, his family couldn't afford their own home. According to Beverly Gherman's "Jimmy Carter," Carter, Rosalynn, and their three children moved into an apartment that was part of a public housing project. Ironically, just before returning to Plains, Carter had endured a rant from his congressional representative on the dangers of public housing.

No injuries came to the Carters during their stay, however. Fortunes (and the weather) turned quickly in 1955, allowing the Carters to leave their apartment, collect income on business ventures, and enjoy a bumper peanut crop.

He was a victim of voter fraud

Accusations of voter fraud can appear to be sour grapes at best and a dangerous undermining of democracy at worst. Per Reuters, it is such a rare crime that a study of over a billion ballots cast between 2000 and 2014 found just 31 cases of fraud. But exceedingly rare events are not impossible ones — just ask Jimmy Carter.

Following in his father Earl's footsteps, Carter decided to run for office. He jumped into a campaign for a Georgia State Senate seat in 1962 against Homer Moore, a well-liked politician with a strong support base, according to Peter G. Bourne's "Jimmy Carter." In Carter's estimation, Moore was an honorable opponent. But Moore had the backing of Joe Hurst, the Democratic party boss of the pivotal Quitman County and a master of dirty politics. Hurst needed a compliant state senator to help protect his sleazy operations and made the (dubious) assumption that Moore, a friend of one of his partners in corruption, would play ball.

Carter was forewarned that the Quitman County vote count might be suspect and dispatched a poll watcher. The watcher reported back accounts of voter intimidation, destroyed ballots, and a complete lack of secrecy around votes. Such practices were hardly rare in Georgia at that time, but Carter refused to accept the fraudulent results of the vote, which put him narrowly behind. An investigation ruled in his favor, and when the election was re-run, Carter came out narrowly ahead.

He could be a dirty campaigner

Jimmy Carter isn't the first name that comes to mind when cutthroat political campaign tactics are discussed. His public image is genteel, and his work outside the White House universally admired. Carter himself has often claimed distance from the ruthless end of politics. As observed by The Nation, he's so consistently and convincingly offered up the image of an honest broker that most of the world accepts him as such.

But a look back at Carter's 1970 campaign for Georgia governor proves that he could play dirty. His opponent in the Democratic primary was former governor Carl Sanders. Sanders was popular, forward-thinking on racial equality, and mentioned as a potential vice president to the Kennedys (per the Atlanta Journal-Constitution). While Carter had shown moral courage on racial issues in the navy and as a businessman, he was quick to appeal to segregationists during the campaign. He complained that Sanders shut George Wallace out of Georgia, tied him to controversial Black legislators, and put in appearances at segregated schools. Leaflets turned Sanders' part-ownership of the Atlanta Hawks against him with photos of him and the Black athletes, designed to alienate racist voters.

Carter's denials of involvement with the leaflets were unconvincing. He also smeared Sanders with vague insinuations of corruption as "Cuff Links Carl" (per "Redeemer: The Life of Jimmy Carter"). The dirty tactics got Carter the nomination and the governorship. Once in office, he worked to end segregation, but Sanders never forgave him.

He holds a curious judicial record among presidents

After becoming president, Jimmy Carter made a lasting mark on America's judiciary. One of his first orders of business, even before being sworn in, was to convince white supremacist senator James Eastland, chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee, to yield control over federal judiciary nominations to a federal commission (via Slate). This commission's recommendations for appeals and district court judges were often endorsed by Carter and the Senate, and it led to an unprecedented diversification of the federal bench. Carter appointed 40 women and 57 people of minority backgrounds, and he oversaw a significant expansion of the federal judiciary.

Yet Carter never had an opportunity to appoint a justice to the Supreme Court. He isn't the only president not to make an appointment to the nation's highest court; per Fox 29 Philadelphia, William Henry Harrison, Zachary Taylor, and Andrew Johnson didn't get the chance either. But of those four, Carter is the only one to have served a full term in office.

His presidency had a conservative streak

Among the biggest shifts in politics since the 1970s was the loss of liberal Republicans and conservative Democrats. While recent assessments of Jimmy Carter see him as a liberal champion, Carter's own statements put him at the other end of the Democratic Party (via The Nation). "I am basically conservative in my attitude toward government," he said during the gubernatorial race of 1970 (per The Atlanta Journal-Constitution). Carter adjusted his tune on the campaign trail for president in 1976, but in office, he reverted to conservative instincts, often to the displeasure of his own party.

Contemporary reporting from The Washington Post examined the dichotomy between Carter and congressional Democrats. The president reneged on campaign pledges to cut defense spending, prioritized a balanced budget over minimum wage hikes and welfare, and pushed through deregulation. One congressional leader went so far as to complain — not entirely seriously — that Carter's economic plans put him to the right of Richard Nixon.

Tensions were higher in the House than in the Senate, and Carter came to terms with his party. He signed the Humphrey-Hawkins Full Employment Act, a cherished piece of liberal legislation (per The Washington Post). But it was significantly reduced from its initial goal of using the government to ensure full employment down to a symbolic nod toward a 4 percent unemployment target, and some blamed Carter's perceived lack of enthusiasm (per The American Yawp).

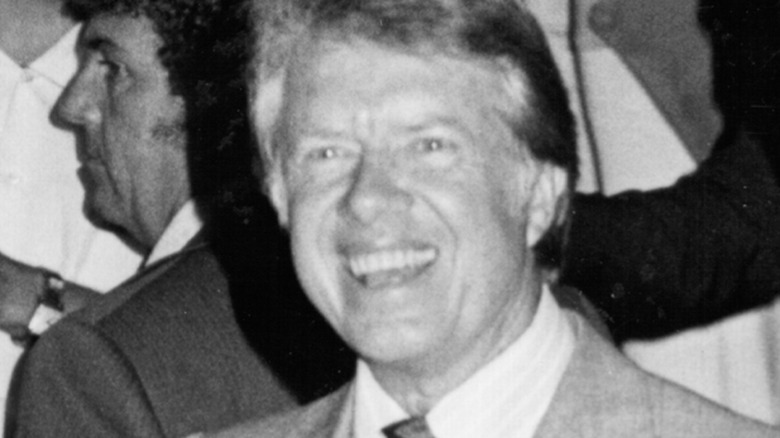

He took a phone call from a stoned Elvis

Richard Nixon famously had his picture taken with Elvis Presley, the most requested photo from the National Archives (per the Washingtonian), and kept in touch with him after the bizarre encounter. But Jimmy Carter could boast actual kinship with the King. "Elvis is my cousin," he once said, referring to a relation through his mother's side (via CBS News). The two would socialize whenever Presley passed through Georgia, with Carter attending his cousin's concerts and Presley visiting with the Carters in Atlanta.

But family connections led to an odd White House phone call in 1977. Carter was still settling into the presidency when a call by Presley was put through. Only months away from his untimely death, Presley was loaded with barbiturates. "He was totally stoned," Carter later told The New Yorker, "and didn't know what he was saying. His sentences were almost incoherent." Carter eventually realized that his cousin wanted a pardon for a sheriff he knew who had run into legal trouble. Since the sheriff hadn't even been tried yet, there wasn't anything Carter could do. He tried to explain this to Presley and to talk him down from the paranoia and illusions that consumed the rock n' roller in his final days. Of his efforts, Carter said (per The New Yorker), "I don't think he understood that." It was the last time the cousins spoke before Presley's death.

Two government departments were created on his watch

As president, Jimmy Carter oversaw significant deregulation. Airlines, railroads, trucks, and home breweries were relieved of oversight, leading to cheaper travel and a craft beer explosion (per the UVA Miller Center and The Atlantic). But Carter also significantly expanded the executive branch of government. According to PBS, he introduced the Ethics in Government Act, established FEMA, and was responsible for two new cabinet-level departments.

The Department of Education had existed before Carter's time. Per Politico, Andrew Johnson originally created it in 1867. But it only lasted one year, a victim to Reconstruction politics and questions about the government's role in education. Carter pushed through a new Department of Education in 1979 to help improve federal education programs. It faced significant opposition in Congress, and disputes about the government's role in schools continue to dog the department, but Carter's incarnation of it still exists today.

Carter also oversaw the creation of the Department of Energy, in part to implement his ambitious policy in that area (per The Carter Center). That agenda was put through in two large packages during his term, with provisions for everything from supply regulations and oil stockpiling to funding for renewable energy and a new generation of nuclear reactors. It all represented Carter's most significant domestic success, though he received very little credit for it while in office.

Jimmy Carter, Cold Warrior

In the collective memory of the Cold War, Ronald Reagan is the president most strongly associated with the latter stages of that conflict. Reagan's friendly relations with Mikhail Gorbachev helped to bring tensions to an end (see History), though his tough rhetoric during the 1980s led observers, then and now, to brand him a warmonger (see The Christian Science Monitor and CESRAN). But it was Jimmy Carter — soft-spoken, cardigan-wearing Jimmy Carter — who began escalating Cold War tensions well before Reagan entered office.

It was Carter who moved to take advantage of the failing Soviet economy of the late 1970s (via The Conversation). With agriculture a weak point for the communist state, Carter's administration imposed an embargo on importing grain into the USSR. Elsewhere, he denied the Soviets significant international prestige when he promoted a U.S. boycott of the 1980 Moscow Olympics. Carter also turned soft power on the Soviets by openly attacking their human rights record.

The CIA began arming the mujahideen in the Soviet-Afghan War under Carter's administration. According to The Nation, Carter and his national security advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski anticipated that such aid (delivered through an elaborate workaround, the Symington Amendment) would drive the Soviets to invade Afghanistan and become trapped in their own Vietnam. When the invasion did come in 1980, Carter articulated the Carter Doctrine in his State of the Union address, voicing a willingness to use military force to safeguard the Persian Gulf for U.S. interests.

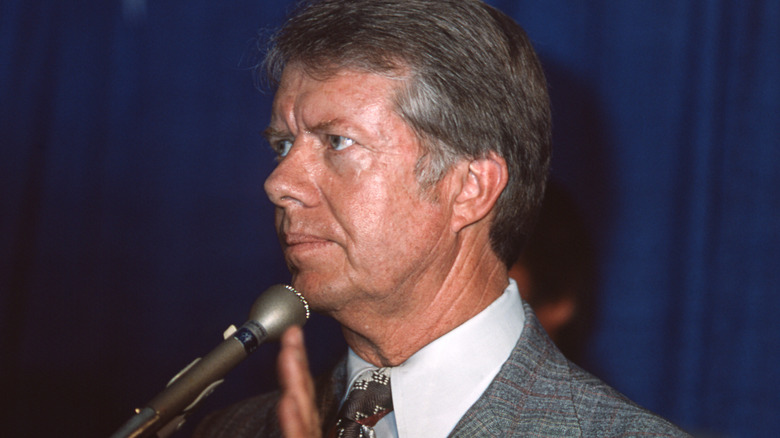

He had image problems

Jimmy Carter struggled with his political image as far back as his time in the governor's mansion in Georgia. According to the UVA Miller Center, he earned a reputation in those days for arrogance and self-righteousness that alienated his fellow Democrats in the state legislature. As president, he faced the same charges in his relationship with Congress, as he bargained only reluctantly and was often too conservative for Democrats in the House.

Carter also faced bad luck with the media. He came off as dismissive and moralizing with reporters, which may have colored coverage (per the UVA Miller Center). In addition, his tensions with Congress were presented as political incompetence, a speech in response to the energy crisis of the late 1970s was characterized as blaming average Americans for their own woes, and false allegations of corruption against his advisors and his brother Billy tainted him.

The image of Carter as aloof and inept was widespread and persists in many corners to this day, but it's at odds with his accomplishments. Despite his tensions with Congress, Carter managed to steer more of his agenda through Congress than most of his immediate predecessors and successors. For example, the Camp David Accords were a monumental foreign policy success that even Carter's critics acknowledged (per The Nation). But none of these successes translated into an uptick in public approval as the 1980 elections approached.

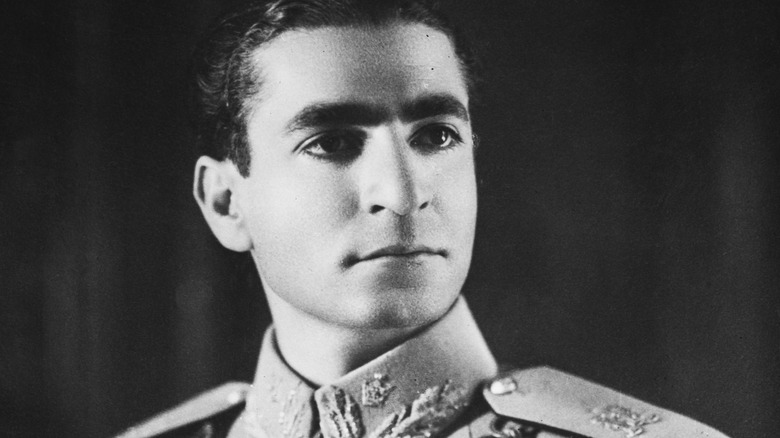

His personal feelings influenced the Iranian revolution

According to The Washington Post, many postwar U.S. presidents counted Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi of Iran as a friend as well as a foreign ally. Jimmy Carter was no exception. His warm relations with Mohammad Reza and the value placed on the monarchy blinded Carter to growing resentment against the regime — resentment that eventually forced Mohammad Reza to flee Iran in early 1979.

The shah settled in Morocco, hoping for a restoration. But before settling there, he received an offer from Carter to reside in a private California estate. Carter seemed unaware of the political ramifications of harboring Mohammad Reza. Even after severe warnings from his ambassador that continued association with the shah would risk a violent response within Iran, Carter didn't make a clean break. Pressure from conservatives and members of his own cabinet — as well as a sense of religious duty — moved him to allow the shah to receive cancer treatment in New York that October. Against warnings, he made no effort to increase security at the U.S. embassy in Tehran.

Outcry against the shah's admittance led to the storming of the embassy in November, setting off the Iran hostage crisis (per History). Negotiations to free 52 of the hostages failed, and a military rescue venture ordered by Carter was a disaster. The crisis contributed significantly to Carter's electoral defeat in 1980 and soured U.S.-Iran relations for decades.