The Complete History Of Mars Exploration Explained

Since humans have looked up to the cosmos, Mars has been an ill‐omen that haunted the night sky. Named after the Roman God of war, Britannica tells us that this planet has long been associated with the brutalities of conflict. Even the earlier Babylonians did not look kindly upon the Red Planet, calling it Nergal after their god of pestilence and death.

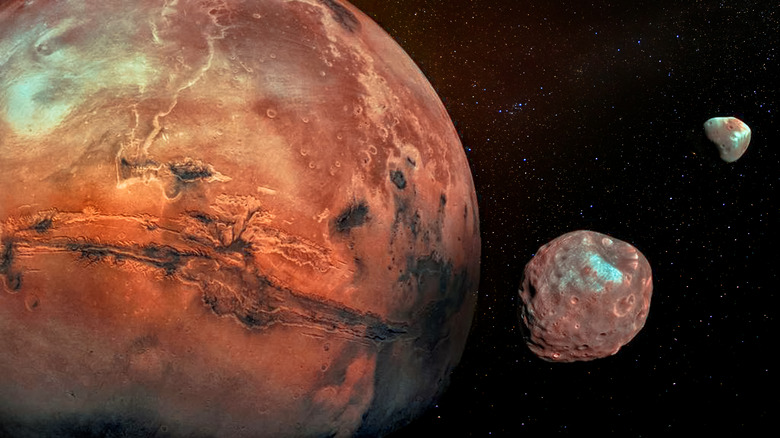

For much of history, Mars was shrouded in mystery and a source of much speculation. As technology improved, the planet's secrets slowly became revealed. Mars was found to be a little more than half Earth's size but less dense so that objects on Mars weigh about a third of what they do on Earth. Suspected canals and landscape that seemed facelike were seen that caused some to ponder whether there was life. In fact, in modern times Mars became a predominant fixture in popular culture. H.G. Wells' "War of the Worlds" featured a Martian invasion of Earth. Edgar Rice Burroughs uses Mars as the setting for the adventures of John Carter.

It was only in the mid-20th century that our thirst for accurate knowledge of the Red Planet started to be slaked. This all began at the height of the Cold War.

The first attempts were made by the Soviets

The story of Martian explorations begins in the mid-20th century with the Space Race. While according to Britannica, the centerpiece of this competition between the United States and Soviet Union was getting humans to the moon, other explorations formed secondary competitions between the superpowers. One of these was Mars.

The Soviets, as explained in NASA's Monographs in Aerospace History, led the way by planning unmanned observational visits to the Red Planet. There was no reason to think that the Soviets could not do this, since they took an early lead in the Space Race with the flight of Yuri Gagarin in 1961. Yet it was not so. An historical log of all missions to Mars is maintained by NASA. This shows that between 1960 and 1969 the Soviets launched eight missions to Mars. All of these failed for a variety of reasons including destroyed spacecraft, failure to reach orbit, and radio breakdowns.

Mariner 4

While the Soviets were coping with failed missions, NASA turned to the Mariner program. Britannica explains that Mariner was the name given to probes that explored the inner planets of the solar system, including Mercury, Venus, and of course the Red Planet. While Mariners 1 and 2 were probes bound for Venus (only Mariner 2 was successful), Mariner 3 was slated to go to Mars. This spacecraft made liftoff, but it quickly lost contact with Earth. Determined, NASA launched Mariner 4 on November 28, 1964. This was a success for NASA as the probe flew by Mars on July 14, 1965, at a range of just over 6,116 miles. Mariner 4 gave humanity the first close up photos of the Red Planet, as well as collect other scientific data.

While Mariner 4 only photographed 1% of the Martian surface, it was still eye-opening for the public and a clear victory for NASA. They followed up this up with new Mars missions, with Mariners 6, 7, and 9 returning clear and awe-inspiring images of the planet between 1969 and 1971.

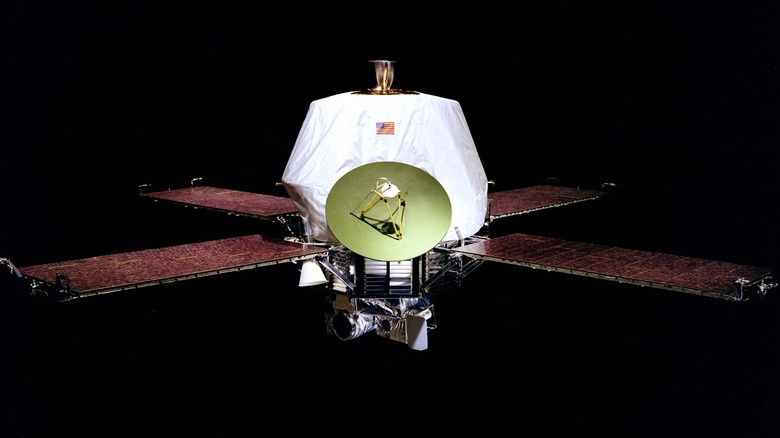

Mariner 9

Mariner 9 was perhaps the most successful probe of the Mariner exploration program. Space.com tells us that this probe was launched on an Atlas‐Centaur rocket on May 30, 1971, shortly after the failure of the Mariner 8 spacecraft earlier that month. According to Discover Magazine, on November 14, 1971, this spacecraft became the first to orbit another planet, beating the Soviet Union's Mars 2 probe by 13 days. It provided the best images yet of the Red Planet.

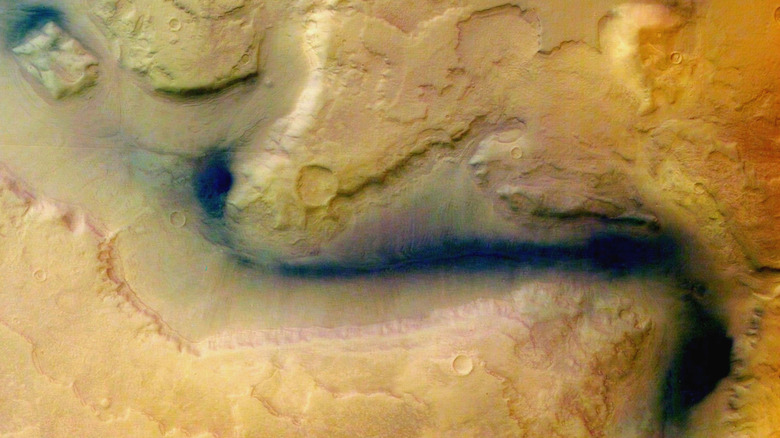

NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory explains how Mariner 9 sent over 7,000 images to Earth while mapping 85% of the surface. Some of these stunning details are explained by Space.com, which included the immense canyon named Valles Marineris. Mariner 9 overcame old assumptions that Mars was a dead and dusty world that was geologically boring. Sky at Night Magazine explains how it found the inactive supervolcano Olympus Mons, which towered over the landscape at 15.5 miles high. Mars had been at least once volcanically active. Furthermore, the shape of the land in various gullies and other eroded features suggested that water had flowed on the Red Planet, as per Space.com. This was especially intriguing for scientists who linked liquid water life.

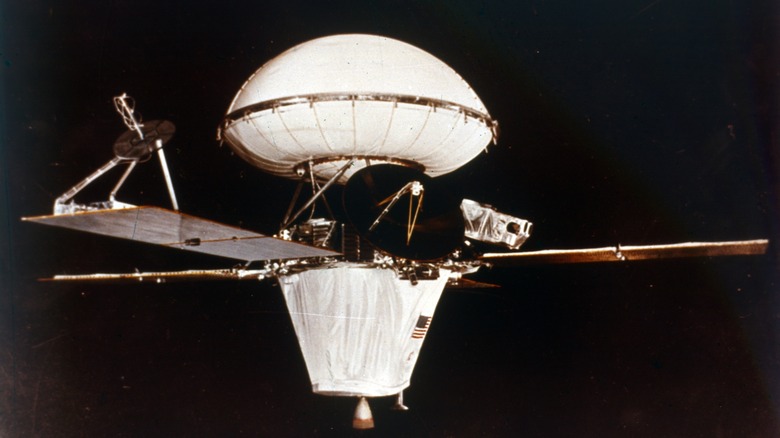

Mars 3

By 1971, the Soviets were smarting from the results of the Space Race as it had only been two years since the U.S. landed its astronauts on the moon. That year, they obtained a half success in Martian exploration. On December 2, 1971, the Soviet Union's Mars 3 had achieved orbit around the Red Planet. Discover Magazine explains how the orbiter released a lander unit whose aim was to reach the surface. As NASA notes, its primary mission was to take scientific data of the atmosphere, collect samples, and analyze other data. But from a political point of view it would be great PR to capture the first surface images of Mars. The rover, called PROP-M, was described by NASA as being a robot tethered to the main lander on skis, which enabled a very constricted range of no more than 49 feet.

The lander touched down successfully with shock absorbers protecting the scientific instruments. The lander's covers opened, and after 90 seconds transmissions began. For all of 20 seconds it seemed a great success, but then quite suddenly communications ceased. The only image that came through was a grainy panoramic that may even just be static. The Planetary Society argues that the lander likely encountered a tremendous sandstorm that overturned the capsule.

The Viking Program

The Soviet Union's Mars 3 program was quickly forgotten because of its very limited success. As far as NASA was concerned, there had been no true successful touchdown on Mars. This set the stage for the space agency's Viking program. According to the Planetary Society, the program consisted of two pairs of orbiters and landers, Viking 1 and 2. NASA's determination to collect the first surface images and data of the Red Planet must have been considerable since they spent $1.06 billion on the program of which most went into the development of a lander. This would makes it one of NASA's most expensive programs ever.

The value of Viking's success is incalculable, however. Both Viking 1 and 2 were successes with both orbiters and landers arriving in 1976. The orbiters collected the best data and images of the Red Planet yet taken. The landers not only took the first ground images of Mars, but they also conducted experiments to test for signs of life. They did not find any evidence of it.

While Viking was undoubtedly a groundbreaking success, its costs were highly criticized. NASA's budget was slashed. This would push the space agency to strive for cost‐effectiveness as Martian exploration continued.

Mars Observer and Mars Global Surveyor

After the Viking Program, NASA's historic mission log of Martian exploration shows there was a long pause, with only the Soviets sending two spacecraft to Mars' moons, which failed. Perhaps it was because of the criticisms of the costs of the Viking program that NASA did not attempt to send another spacecraft to Mars until 1992, as per NASA's Mars Exploration Program. That year saw the launch of Mars Observer, which was more or less a converted commercial satellite. According to Space.com, this spacecraft cost $813 million, about four times the original budget. Unfortunately, Mars Observer spun out of control before achieving orbit in 1993. The cause was a likely fuel tank rupture, so NASA reassessed its strategy.

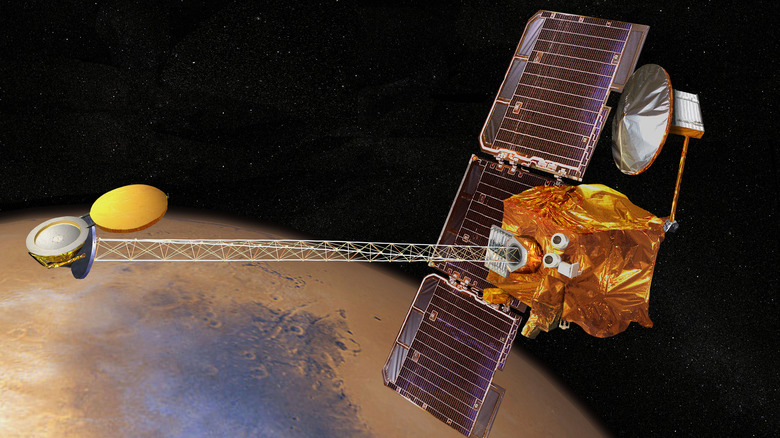

Meanwhile, NASA developed its Mars Global Surveyor mission. This probe attained Martian orbit on September 12, 1997. This mission sent back detailed images of the planet and using a laser altimeter, mapped almost the entire surface. In fact, in some places they were more accurate than what had been mapped on Earth. By February 1, 2001, when its primary mission was over, Global Surveyor had sent 83,000 images back to Earth. The indefatigable spacecraft also lasted far longer than what was anticipated. It only lost contact with NASA in November 2006.

Nozomi

Until the late 1990s, the only players in the Mars exploration game were the U.S. and Russia (since the dissolution of the Soviet Union). However, this was to change on July 4, 1998, when, according to the Institute of Space and Aeronautical Science, Japan launched the spacecraft Nozomi to the Red Planet. NASA explains how Nozomi was Japan's fourth deep space probe and its first interplanetary one. To build up speed, after launch, the probe conducted two gravity-assisted slingshot maneuvers of the Moon and Earth before heading off to Mars.

It was then that problems started. A broken valve leaked propellant, which forced the Japanese Space Agency to reconfigure Nozomi's course. In order to compensate for the lost fuel, Nozomi was sent on two more Earth flybys before it was flung off to the Red Planet. During this time, Nozomi suffered damage to its power and communication systems by solar flares. In fact, for two months, the Japanese lost contact with the spacecraft. The probe finally reached Mars in December 2003, four years behind schedule. However, by then its luck had run out. Nozomi's main thrusters failed, and it ended up in a very elliptical orbit around the sun where it will remain until the Solar System ends.

Mars Pathfinder

With pressure on NASA's budget, it adopted a "faster, better, cheaper" approach to space exploration, as per "Faster, Better, Cheaper," by Howard E. McCurdy. One of its first missions under the new strategy was Mars Pathfinder. As recounted by the Planetary Society, the program, which cost a relatively low $485 million, aimed to set down a lander named "Pathfinder" on the Martian surface complete with a rover named "Sojourner." This would be the first landing on Mars since the Viking program.

According to NASA, Pathfinder launched on December 4, 1996, and successfully landed on the Red Planet in the rocky plains area of Ares Vallis on July 4, 1997, using airbags. Sojourner was released without a hitch and slowly inspected the surrounding area for three months, reports the Plantery Society. While the mission was billed as a demonstration of technology — and in this regard it was highly successful in showing how Martian exploration could be conducted — it also revealed important scientific information. For example, the morphology of the rocks suggested the presence of running water in the past, as well as magnetism in the planet's dust particles that may have been pushed to the surface through a water cycle. All of this hinted that the planet may have been habitable in the past.

Mars Odyssey

While NASA's Pathfinder was a great success, several of the other missions of the late 1990s "Faster, Better, Cheaper" campaign were not. Between 1998 and 1999, NASA launched two missions to the Red Planet: Mars Climate Orbiter and Mars Polar Lander. Both failed upon arrival to the planet. Mars Polar Lander may be considered a double loss since it carried with it a submission of two probes, which NASA intended to use to penetrate the surface, as per NASA.

These failures led NASA to begin to modify its "Faster, Better, Cheaper" approach. The result was Mars Odyssey, a spacecraft which cost, according to Space.com, $297 million. It entered into Martian orbit on October 4, 2001, after a relatively brief voyage of 200 days. Mars Odyssey was designed to investigate the planet's atmosphere, scan the surface with sensors, and also act as a relay station for future ground exploration.

Perhaps the mission's most exciting discovery was the likely presence of hydrogen about a mile below the surface, which hinted at the presence of water. Since those initial days, Mars Odyssey has provided information on Mars that no other spacecraft could since it is still in operation today. It has found salt deposits, probable caves that could possibly harbor life, and close observations of yearly cycles in the Martian environment. By 2021, over 1 million high resolution images of Mars have been sent back to Earth from this intrepid piece of equipment.

Mars Express, Spirit, and Opportunity

It seems that the success of Mars Odyssey began to open the floodgates to Martian exploration. Britannica describes how the European Space Agency entered the fray with its Mars Express program, which attained orbit on December 25, 2003, and started taking even more detailed images of the planet. Mars Express was mainly successful in that its orbiter with its instruments possibly detected liquid water. This was added onto findings of methane, which was another sign that there may be microbial life on Mars. Unfortunately, the rover the spacecraft carried, Beagle 2, failed to make contact after landing. It was later found that its solar panel did not open properly.

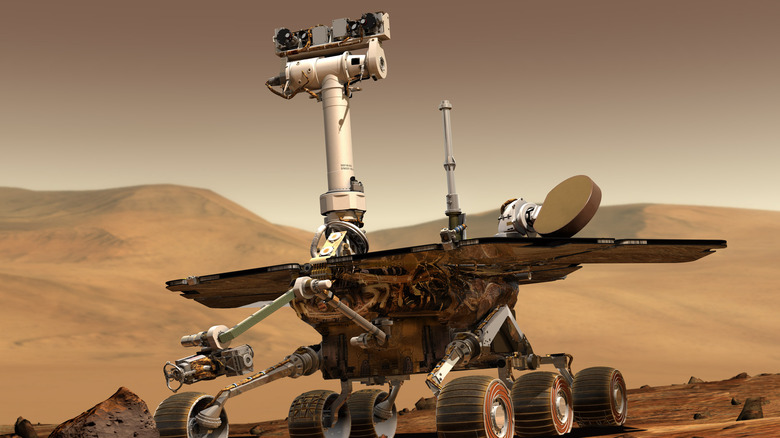

Meanwhile, NASA launched a mission to follow up on the success of the rover Sojourner. In January 2004, the rovers Spirit and Opportunity landed on the Red Planet. These robots acted as field geologists and using tools tested and analyzed rock all the while taking fantastic images of the landscape in full color. Their research began to paint a picture that arid Mars had a wet past. Amazingly, these pair of rovers lasted far beyond the anticipated 90 day mission. Spirit lasted for six years and had explored nearly 5 miles, while Opportunity lasted over 14 years and racked up 28 miles. NASA, it should be said, was very careful about sending the rovers too far abroad.

Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter and Mars Phoenix Lander

NASA racked up another big success in its next mission: the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter. This spacecraft entered Martian orbit on March 10, 2006, and is still in operation today. The Planetary Society tells us that the main goal of the orbiter is to study Martian geologic history and its current climate. It is hoped that through the data it collects scientists can understand why what once may have been a habitable world is now a wasteland. To do so the orbiter is armed not just with three powerful cameras but also radar that can look under the surface for ice, sensors to examine the makeup of the atmosphere, and devices that map minerals at the surface.

Confirmation of ice on Mars came with NASA's Phoenix Mars Lander, which as reported by Space.com, landed at the planet's northern pole on May 25, 2008. The lander followed up on the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter's indications of ice and retrieved samples from digging at the surface. To treat the icy samples, the lander even had miniature ovens to heat the ice. It even detected snow above, which vaporized before landing. Unfortunately, the lander ceased communications after three months. Still, it was now evident that Mars had water on it in the form of ice, and that it went through regular seasonal cycles of precipitation.

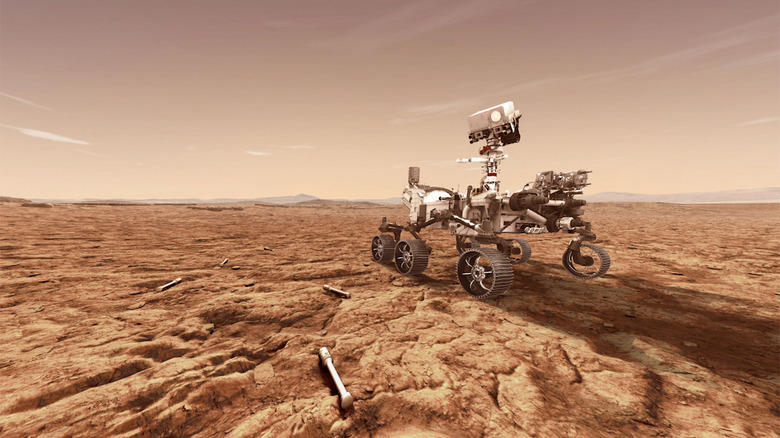

Curiosity and Perseverance

The increase in Martian exploration has made Mars the most well‐understood planet outside of Earth in our solar system. But questions still need to be answered, particularly if Mars had harbored life in its deep past, and if it has the potential to maintain life in the future. NASA's Curiosity rover seeks to help answer those questions. After touching down on the Red Planet in August 2012, this rover has been exploring the Gale crater gathering air, soil, and rock samples for analysis. To do this, Curiosity has an assortment of scientific tools, including a robotic arm, multiple cameras, a spectrometer, and lasers.

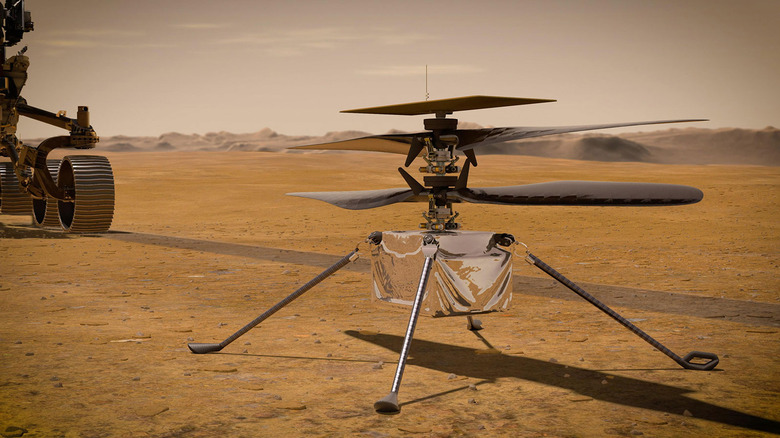

More advanced than Curiosity is the Perseverance rover, which landed on February 18, 2021, in the Jezero Crater. In its quest for microbial life, the rover carries seven instruments, including a device to test if oxygen can be produced from Martian carbon dioxide, ground‐penetrating radar, and a camera device that can detect the chemical composition of materials. Perseverance also has the capability to drill core samples and even package them in tubes for eventual retrieval. Remarkably, Perseverance also transported a miniature helicopter to Mars, named Ingenuity, as a technology demonstration. When the little drone took off on April 19, 2021, it was the first time powered flight took place on another world.

Mars is getting crowded

While the U.S. from day one has clearly been dominant in the exploration of Mars, other countries have launched successful expeditions. According to NASA, in 2014 India successfully put a spacecraft in orbit around Mars to study the planet's atmosphere and surface. In addition, the Planetary Society reports that China's Tianwen‐1 mission, which launched in 2021, was the country's first successful foray into Martian exploration. It also was the first country able to deploy a rover to Mars' surface other than the U.S. That same year, the United Arab Emirates successfully placed a satellite into orbit around the Red Planet. Space.com reports that the orbiter, which used a Japanese rocket to launch, will study the planet's atmosphere. It is the first interplanetary space mission headed by an Arab‐Islamic country.

It seems to be that even as Earth faces environmental crises, looking to Mars can provide hope. Maybe it can be transformed into a new Earth, fit for habitation but without the headaches. However, it may be better to consider the thinking of astrophysicist Neil DeGrasse Tyson who told the Guardian, "If you had the power of geoengineering to terraform Mars into Earth, then you have the power of geoengineering to turn Earth back into Earth."