Shark Expert On Why Reunion Island Is A Hotbed For Shark Attacks - Exclusive

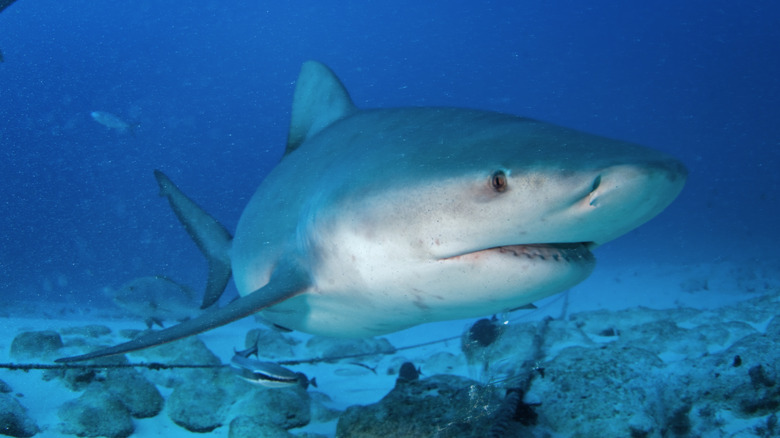

Shark attacks are exceedingly rare but shark bite-related fatalities still do happen. Nowhere more so than in the water around Réunion island, a small French territory in the Indian Ocean, near Madagascar (via Britannica). According to Smithsonian Magazine, it's unclear just why shark attacks are such a problem in the area. What might contribute to the problem, though, are bull sharks, a common species in nearby waters. Large and aggressive, bull sharks are among the most dangerous type of shark for humans, as the National Wildlife Federation explains.

Whatever the cause, shark danger has become such a problem at the scenic French territory that surfing and swimming are now banned, as Men's Journal reports. Shark expert Dan Duane hosts the Sony Music Entertainment podcast, "Réunion: Shark Attacks in Paradise." In it, Duane recounts a few of the most harrowing and fascinating stories of shark attacks and survival near Réunion. Speaking exclusively with Grunge, Duane weighs in on what makes the waters so unsafe, and what steps local authorities have taken to mitigate the shark attack risk in the area.

Just how prevalent are shark attacks around Reunion island?

When asked just how risky it is to swim or surf near Réunion, Duane tells Grunge that, like many things, it's all relative. "Statistics are a funny thing," the podcast host continues. The chance of a surfer being bitten by a shark in California, for example, is around one in 17 million, as the podcast host goes on to note (via Shark Stewards). Based on those odds, there's next to no shark-attack risk in the waters off California, "But we're still plenty scared out here," Duane says.

On Réunion Island, where Duane's podcast takes place — and where most shark attacks in the Réunion area come from bull sharks, Duane adds, "Or, as the French call them, 'les bulldogues,”' or bulldog sharks, Duane says — those same odds are calculated at one in 100. That still might not sound like much, he admits. "If you heard 'one in a hundred' without context, you might think, 'Hey, that's not so bad,'" Duane says. But, if you hear it next to the California number, you might think, 'Okay, now that's really bad,' he continues.

What steps have been taken to lower the frequency of shark attacks?

To help keep people safe, authorities on Réunion Island have gone so far as to ban swimming and surfing. Basically, they just ordered everybody out of the water, Duane adds. Technology has also played a part in shark-attack prevention in the form of so-called smart drum lines, or baited fish hooks outfitted with GPS transponders anchored to the seafloor and to floating buoys. "Whenever something bites that big hook, the transponder alerts a fisherman," Duane says. If that hook has caught anything other than a big bull or tiger shark, the fisherman lets it go.

If it has caught a big bull or tiger shark, though, the fisherman then kills the fish. "This has been very controversial," Duane says, adding that a lot of reasonable people object to the practice. On the upside, the number of sharks caught this way in the area has fallen from a few dozen a year when the program was launched to just two in 2021, he adds. As Duane goes on to note, perhaps the most unusual measure taken are teams of underwater shark lookouts, people paid by the government "to swim around looking for sharks so that other people can safely surf nearby," Duane says.

And, what happens when a shark's spotted? "Quite a lot," Duane continues. "At nearby beaches, lifeguards raise red flags and order everyone out of the water; but there are also shark-warning apps now on people's phones, and social media accounts that push out news whenever there's a sighting," Duane says.