The Untold Truth Of The Council Of Trent

Between the 14th and 16th centuries in Europe, the continent was transitioning from the Middle Ages to the Renaissance, and people were redefining what their lives meant and how they lived (via History). The Middle Ages began around the 5th century and were largely shaped by the rise of Christianity and political dynasties (via Britannica).

However, for the Catholic papacy, it was not always smooth sailing. Pope Gregory I established the "Medieval Papacy," but it was subjected to the constant political instability that plagued the Middle Ages. By the beginning of the Renaissance in the 14th century, papal power was declining due to widespread corruption and the Great Schism — which had split the church in two.

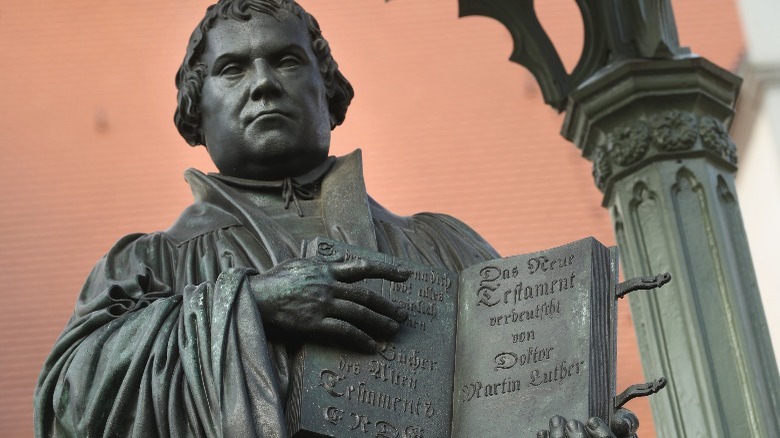

In the 15th century, the role of the pope gradually became more secularized, as financial and political matters started to overcome religious ones. In addition, Martin Luther (pictured) kicked off the Protestant Reformation, increasing pressure on the church. Finally, in 1545, the Vatican called for the Council of Trent to reestablish its religious authority. What followed was an incredibly momentous event in Christian and European history. This is the untold truth of the Council of Trent.

The Council of Trent was really about Martin Luther

By the mid-16th century, the Catholic Church found itself at a crossroads. The church was besieged by the Protestant Reformation, which had begun in 1517 when Martin Luther wrote his famous Ninety-Five Theses (via Britannica). The document explicitly repudiated the Catholic Church's practice of indulgences, which he saw as a "perversion of the doctrine of redemption and grace."

Luther also argued for the doctrine of sola scriptura (via the "Encyclopedia of Catholicism"). Sola scriptura was a rejection of the papal doctrine of dual authority (prima Scriptura). Dual authority held that the interpretation of the Bible could use both biblical and non-biblical sources, like unwritten traditions and teachings. Sola scriptura repudiated that idea and held that the Bible is authoritative by itself, and faith is the only needed justification — not other sources.

In response to the criticisms of Luther and other reformers, the church instituted the Counter-Reformation (via History). The first step in the Counter-Reformation was calling the Council of Trent, which first began in 1545. Yet, as John W. O'Malley shows in "Trent, Sacred Images, and Catholics' Senses of the Sensuous," the Council of Trent was almost specifically directed at Martin Luther himself over the other reformers. The attendees at Trent, though they felt sympathy with reformers, saw Luther's teachings about justification as heretical, and they repudiated the doctrine of sola scriptura upon the council's closure.

It was delayed by eight years

Prominent reformers like Martin Luther, John Calvin, and Huldrych Zwingli first started to criticize the papacy and the Catholic Church in the 1510s, and initially, there was little reaction (via History). Pope Clement VII, who reigned from 1523-1534, was indecisive and allowed the Reformation to grow without stepping in to try and stop it (per Britannica). However, the Reformation was not limited to just Germany and the immediate reach of the Holy Roman Empire, but it quickly started to spread through Switzerland, France, and England.

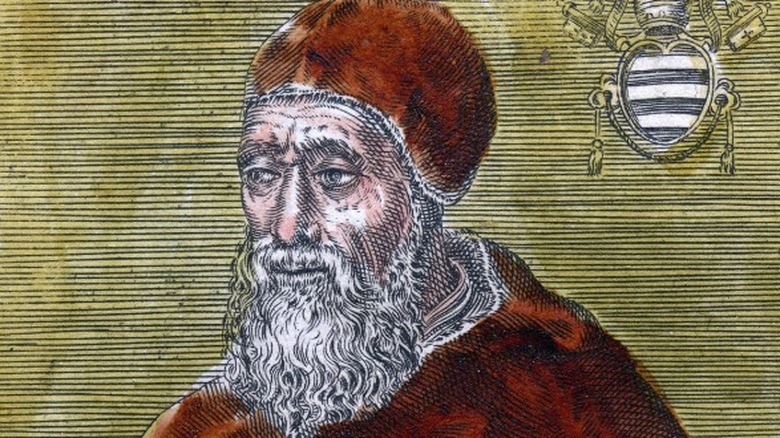

Before long, the papacy was surrounded on all sides by potential heretics. Clement's successor Pope Paul III (pictured), finally called for the Council of Trent to begin in May 1537, as the first step toward putting an end to the Protestant heresy (via Britannica). However, it was continually delayed and postponed by antagonistic rulers.

Finally, on December 13, 1545, the Council of Trent convened in Trento, Italy, a full 8-and-a-half years after Pope Paul III had originally called for it.

The Council of Trent was actually three different councils

While many people think that the Council of Trent was just a short-lived ecumenical council, in reality, it lasted almost two full decades. The council first met in December 1545 and held its last session in 1563 (via John O'Malley in "Trent, Sacred Images, and Catholics' Senses of the Sensuous"). One of the big reasons that it extended so long is that it did not stay in session the entire time, but rather it met in three separate periods. Furthermore, each iteration was attended by different numbers of bishops, and the final council had nearly 10 times the amount of clergy as the first one.

The council was in session from 1545-47, 1551-52, and 1562-1563. The first council was interrupted by renewed fears of the Black Death, as well as the threat of Protestant military attacks (via Britannica). The second council was also suspended due to military activity.

However, even though the councils were suspended, they still achieved goals during each period. Both the first and second councils made several decrees regarding reformers and interpreting the Bible. The third council had the biggest reforms regarding the clergy, but each one was incredibly important for the larger Counter-Reformation.

It was almost the Council of Balogna

The Council of Trent was held in the Italian city of Trento, which is actually where the name Trent comes from (via Britannica). Trento had become Christianized around 500 A.D., and by the mid-11th century, it was firmly within the control of the Holy Roman Empire.

However, Trento was not even the original city that the council was supposed to take place in. When Pope Paul III first called upon the council to start in May 1537, he wanted it to convene in Mantua, Italy. However, the years of delays caused it to instead be held in Trento, which eventually became the council's namesake.

Another interesting fact about the council's location is that in 1547, when the first council was suspended, Paul III tried to get it moved to Bologna, Italy, to restart as soon as possible. However, opposition from the emperor ultimately caused the council to be prorogued until 1551, and prevented the Council of Bologna from ever sitting.

The Old and New Testament became definitively set within Catholicism

The Council of Trent issued many decrees that had a wide impact on Catholicism, but many people do not realize that it explicitly dealt with the books that form the Christian Bible. When Martin Luther started the Protestant Reformation in 1517, one of the tasks he set upon was to translate the Bible from Latin to German. Eventually, he published his translation of the New Testament in 1522 and the Old Testament in 1532 (via the University of Arizona).

While Luther's original translation published the entire Bible, even those parts he found uncanonical, the Protestant Bible is actually different from the Catholic Bible. The Catholic version has seven more books in the Old Testament, as well as multiple other holy writings (via the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops).

Part of the Council of Trent was aimed at solidifying what the pope wanted to be recognized as the Bible within Christianity. The council solidified the 27 books of the New Testament, and 46 books of the Old Testament, which was based on the Latin Vulgate (per the Council of Trent's "Decree on the Canonical Scriptures" via Hanover College). The Latin Vulgate is the original Latin translation of the Bible by St. Jerome in the late 4th century, and — due to Trent — continues to be recognized today as the definitive version of the Bible within Catholicism.

Original sin was defined

Another important aspect of Catholicism that the Council of Trent surprisingly debated was the belief in original sin. Original sin is the doctrine that every human being is born into a state of sin, or moral evil (via Britannica). Humans originally acquired the condition of sin when the first human, Adam, broke God's commandment and ate from a specific tree in the Garden of Eden. As punishment for his transgression, he was cursed with sin, which was then hereditarily passed down to all of his descendants — which Catholic tradition holds is every human being ever born on Earth.

According to the Council of Trent's "Decree Concerning Original Sin" (via Hannover College), this doctrine of original sin was to be the only recognized interpretation, and anyone who disagreed with it was to "be anathema." The remedy for "remitting" original sin is to be baptized — which the council's decree explicitly suggests. In total, the decree had five separate points, and being that it was discussed at one of the earliest Trent sessions, it must have been high on the church's agenda, and thus deemed relatively important.

One pope refused to call the council

When the Protestant Reformation first broke out, the papacy was reluctant to seriously confront it. Pope Clement VII refused to do anything about it, and it was not until Pope Paul III in 1537 that the ball started rolling for the Counter-Reformation when he called for the Council of Trent (via Britannica). Yet, the council was interrupted in 1547 and 1552, due to the Black Death and military engagements.

When Pope Paul IV (pictured) took over in 1555, he refused to reconvene it again (via Britannica). His overall handling of the Protestant Reformation was weak, and his policies even led to the victory of Protestantism in England. Paul IV preferred to use other methods of reform, like congregations or special commissions, and he disliked the conciliar style of Trent. He was able to institute several reforms for the clergy and stop some abuses, even without Trent, but he took a very stern approach.

The Council of Trent was eventually called again in 1562, when the new pope, Pius IV, reinstated it for its final period (via Britannica).

It firmly codified the doctrine of transubstantiation

In addition to the many other aspects of Martin Luther's writings that upset the Catholic Church, were his views on the consecration of bread and wine during the Eucharist — also known as Holy Communion (via Britannica). Luther argued for the doctrine of consubstantiation, which held that during the Eucharist, Jesus' body coexists with the bread and the wine as equal parts (via Britannica).

This might seem like an insignificant, slightly different interpretation of the Eucharist, but to the Catholic Church, it was practically heresy. The church officially preached the doctrine of transubstantiation, which instead held that Jesus' body did not simply coexist with the bread and wine, but rather it actually physically became the bread and wine itself. It only still appeared to look like food and drink to the human eye, but in reality, it had transformed into the body and blood of Christ.

The issue of the Eucharist was discussed at the Council of Trent, and unsurprisingly the doctrine of transubstantiation was officially declared the correct interpretation under Catholic dogma during the 13th session in the first chapter of the "Decree Concerning the Most Holy Sacrament of the Eucharist" (via Hannover College). The decree held that "our Lord Jesus Christ, true God and man, is truly, really, and substantially contained under the species of those sensible things [bread and wine]."

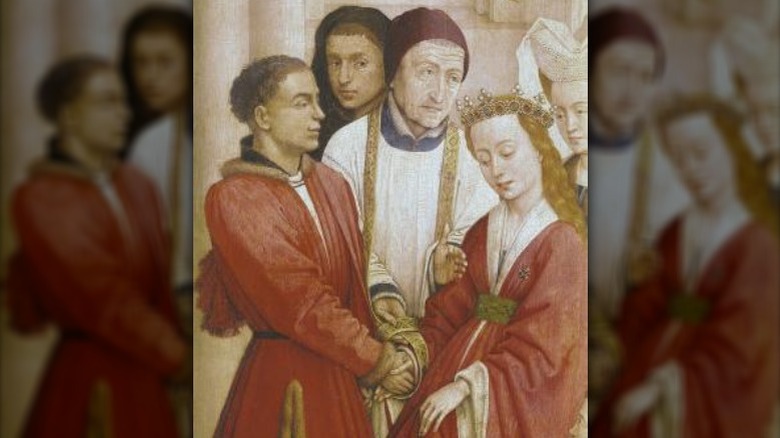

The Council of Trent made several marriage decrees

Another somewhat surprising topic the Council of Trent undertook related to marriage: During the 24th session of the third period of Trent, it dominated the proceedings. The "Doctrine of the Sacrament of Matrimony," (via Hanover College) explicitly stated that marriage was "one of the seven sacraments of evangelic law," and completely repudiated the idea of divorce. It went to great lengths to state all of the reasons that could not be considered grounds for divorce, including adultery and "irksome cohabitation" — which meant divorce for loud snoring was sadly off the table.

It also outlawed polygamy and stated that anyone who preached the idea was to "be anathema." Another decree the "Doctrine of the Sacrament of Matrimony” made was that all affairs related to marriage were to be the purview of ecclesiastical, rather than secular, judges. It also decreed that virginity and celibacy were more important than marriage, and that the church had every right to ban the "solemnization of marriage" at certain times of the year. Furthermore, anyone suggesting the church's temporary ban on solemnization was "tyrannical superstition, derived from the superstition of the heathen," was to again "be anathema."

It is partly responsible for the calendar we use today

One might think that because the Council of Trent was established by the Catholic Church, its reforms and decrees only affected and shaped those within the Catholic faith. So it might be pretty shocking to learn that Trent was actually the impetus for the modern calendar that most of the world currently uses today. Prior to the mid-15th century and the Council of Trent, the Christian world relied on what was known as the Julian calendar (via Britannica).

However, the Julian calendar was flawed. It was not quite as bad as the Roman Republic Calendar, which originally did not count 61¼ days of the year, and in its final iteration, it consisted of only 355 days (per Britannica). Yet, the Julian calendar still overestimated the length of a year by 11 minutes and 14 seconds, which resulted in a phantom day being added to the calendar every three centuries. This caused several problems for church holiday scheduling, especially in reconciling the observance of Easter with the vernal equinox.

Finally, during the third period of the Council of Trent, the council issued a decree that called for a new calendar to be created that would fix the problems of the Julian calendar. Eventually, 20 years later, Pope Gregory XIII officially announced the new calendar, which bears his name. Most of the world, including the U.S., still uses the Gregorian calendar today, an unappreciated tribute to the Council of Trent.

None of the popes attended the council's sessions

When the Council of Trent first opened on December 13, 1545, it was Cardinal Giovanni del Monte who officially inaugurated its start (per Britannica). Del Monte was the legate of Pope Paul III, who was the person who initially called for a council to convene eight years prior. This leads many to ask why it was del Monte and not Paul himself who presided over the official beginning of this important ecumenical council.

The reason, incredibly, was that the pope was actually legally forbidden from attending the council. The Catholic Church was part of the larger Holy Roman Empire, which was headed by Emperor Charles V (pictured). As such, the church had to negotiate with Charles V before they could hold a large international gathering like Trent. As part of the negotiations with Charles V during the lead-up to Trent, he insisted that none of the popes be allowed to attend any of the sessions (per John W. O'Malley in "Trent, Sacred Images, and Catholics' Senses of the Sensuous").

Charles V's goal with Trent was to create peace between the Protestants and Catholics, which he had been trying to do for years (per the Concordia Seminary in St. Louis). He finally brokered the Peace of Augsburg, which ended the religious conflict between Protestants and Catholics, in 1555 — a year before he officially abdicated the throne. However, Trent still went on for several more years, outliving Charles by nearly a decade.

Nearly 600 texts were made heretical

One of the lasting implications of the Council of Trent was the banning of hundreds of books. According to historian Joshua J. Marks at World History, the Catholic Church had been fighting against the publication of books for decades. Johannes Guttenberg had invented the printing press a century earlier and released the famous Gutenberg Bible, but it was Martin Luther who really created the first frenzy surrounding the publication of books. Luther's Ninety-Five Theses and German translation of the New Testament immediately became "bestsellers," and Luther was one of the most read translators in all of Germany (via Marks at World History).

Luther was not the only one who wrote texts the Catholic Church deemed heretical, as John Calvin and Huldrych Zwingli also ran afoul of the church for their publications (per Marks). To combat the widespread reading of these texts, Pope Paul IV created the "Index of Forbidden Books." The Council of Trent then took this list and revised it, which resulted in it being officially released in 1563, and included a 10-point introduction.

Among the banned books in the "Index," were anything written by Luther, Calvin, or Zwingli and several other "heretical" reformers. Per PBS, 583 total books were banned through the "Index," including the majority of biblical translations from Latin.

The Council of Trent dealt with clerical celibacy

Even before the Council of Trent, celibacy had long been an issue within the Catholic Church. It actually stretched back to the first century A.D., when the practice began among Christians who were worried about the Apocalypse (via Britannica). The issue started to involve clergy in the 4th century, when the Council of Elvira in Spain forbade priests and bishops from intercourse — even if they were married.

Over the next millennium, the church officially endorsed clerical celibacy and enshrined it into law, but it was unevenly enforced. In fact, Pope Alexander VI actually fathered children — clearly a violation of his celibacy vows. During the Reformation, many Protestants, led by Martin Luther — who rejected his own vows — denounced and repudiated the idea of clerical celibacy.

In response to the Reformation, in the third period of Trent, the council decided to make a definitive ruling on the future of celibacy in the church. According to the Vatican, they affirmed the doctrine of clerical celibacy and the prohibition on clerical marriage, refusing to heed any calls for reform. The council also decided to found seminaries that explicitly taught the practice of celibacy to potential clergy members from their childhood. The Catholic Church still follows the decrees of Trent on clerical celibacy, nearly 700 years later.