The Unexpected Connection The First Woman To Serve In Congress Has To Slavery

The first woman to ever sit in the United States Senate was Rebecca Latimer Felton, a 19th-century suffragette. Felton was a political force in her own right whose advocacy career aligned with the political career of her senator husband, William (via Georgia Encyclopedia). As a writer and a speaker she championed a number of causes: white women's suffrage, white feminism, temperance (pre-Prohibition), and 19th century agrarian reform. As the first woman to sit in the Senate, her legacy was fixed. According to a featured Senate biography, Rebecca's greatest contributions were her views on gender equality (pro). Her views on racial equality (against) are hardly printable, let alone worthy of Senate featured biographies or ornamental plaques.

Rebecca Latimer Felton was a white supremacist who enslaved human beings for roughly 30 years. She advocated white women's suffrage (and only white women's), but also segregation. She wanted to improve the conditions of the white agrarian worker, but she also wanted Black men lynched (via The Washington Post). Like many of those whose legacies have been rinsed pure by the passage of time, Senator Rebecca Latimer Felton's true story is much darker and far more complex than history would make it.

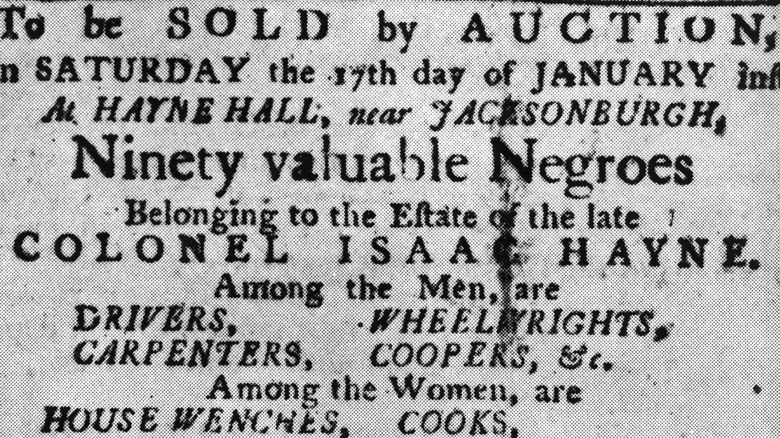

Her wedding dowry included enslaved human beings

From the day she was born in 1835 until the end of the Civil War in her 30s, slavery was intimately interwoven with the fabric of Rebecca Latimer Felton's day-to-day life. Born to a wealthy political family in Decatur, Georgia, Rebecca was de facto Southern royalty. Her family lived on a plantation. Enslaved people were probably present at her birth, and enslaved people likely cared for her as a child.

In 1852, Rebecca graduated from Madison Female College. When she turned 18 one year later, she decided to marry the commencement speaker from her graduation, a doctor named William Felton who was 12 years her senior. When Rebecca Latimer and William Felton married, she brought her dowry: two enslaved individuals (via The Washington Post). Rebecca moved to Cartersville, Georgia in 1853 and became mistress of her new husband's plantation (via New Georgia Encyclopedia).

She came from a long line of enslavers

Rebecca was active in her community as any wealthy white Southern woman would be (via New Georgia Encyclopedia). It wasn't until slavery was outlawed and the South was defeated that she gave up her so-called business — managing enslaved human beings. (In her memoir, "Country Life in the Days of My Youth," Rebecca writes at length on the so-called business of enslaving people. At one point on page 78, she refers to a 12-year-old girl's pregnancy as profitable.

Rebecca came from a long line of enslavers. Her father owned human beings, his father owned human beings, and his father owned human beings before that (via "Country Life in the Days of My Youth," page 259). Once slavery was finally outlawed in practice in the South, Rebecca kept that legacy alive with her worldview. She was adamant, outspoken, and unwavering in her advocacy for white supremacist beliefs. She believed white people were entitled to superior treatment, privileges, and power; she believed people of all other races — Black people in particular —were inferior and worthy of oppression and abuse.

She was a vocal white supremacist who encouraged lynching

Rebecca Latimer Felton espoused white supremacist views with all the brazenness of an ex-enslaver. She was an avid supporter of segregation; she openly advocated the genocidal practice of lynching (via United States Senate Archive). A remark she made on lynching would be mentioned in newspapers, quoted by young men, and, according to The Washington Post, would possibly even set off a chain of events that would end in a massacre in Wilmington, North Carolina, in 1898 (via The Washington Post).

By the late 1890s, Rebecca was in her early 60s, with decades of campaigns, causes, and accumulated political clout behind her. She was addressing a congregation of farmers' wives when she lapsed into a soon-to-be-oft-quoted diatribe. According to The Washington Post, Rebecca told the white farmers' wives that the greatest threat they faced was Black men who might want to rape them (most seem to agree this actual claim was baseless). She then outright advocated lynching for "protection": "[I]f it needs lynching to protect woman's dearest possession from the ravening human beasts, then I say lynch, a thousand times a week if necessary," she infamously said.

She campaigned for white women's suffrage

When Rebecca's husband William lost another bid for re-election, the political power couple joined each other to campaign across Georgia (per New Georgia Encyclopedia). Rebecca's preferred campaign goals were white women's suffrage (voting rights) and temperance (a sobriety movement), according to The Washington Post.

When William Felton died in 1909, Rebecca began to compile her memoirs and writings, the first of which was published in 1911 ("My Memoirs of Georgia Politics"). She would later publish a memoir of her upbringing ("Country Life in the Days of My Youth") wherein she discusses slavery at length. She still believed in segregation (via United States Senate Archive).

In 1919, the Nineteenth Amendment was passed, granting (white) women the right to vote. It was ratified in 1920. White women — but few Black women, per PBS — could vote for the very first time in U.S. history. Rebecca Latimer Felton was 85 years old.

In 1922, she was the last enslaver to take the U.S. Senate oath of office

It wasn't until she was 89 years old that she had her day in the Senate. When the Senator from Georgia unexpectedly died in 1922 (via Georgia Public Broadcasting), the Governor of Georgia appointed Rebecca Latimer Felton to take the Senator's place temporarily. It was a valuable chance to curry favor with the nation's newest voting bloc: white women. (He also wanted the seat permanently for himself.) As a suffragette, a known political presence through her husband, and one tied to the old white plantation South, Felton was be a popular choice among Georgia's white women (via United States Senate Archive).

Rebecca Latimer Felton — woman, enslaver, suffragette, white supremacist — was sworn in to the Senate on November 21, 1922 (via The Washington Post). She served a symbolic 24 hours before the next Georgia Senator took office. According to another article by The Washington Post, 1,800 representatives have enslaved Black people. Rebecca Latimer Felton was the last enslaver to ever serve in Congress.