The Untold Truth Of Salman Rushdie's The Satanic Verses

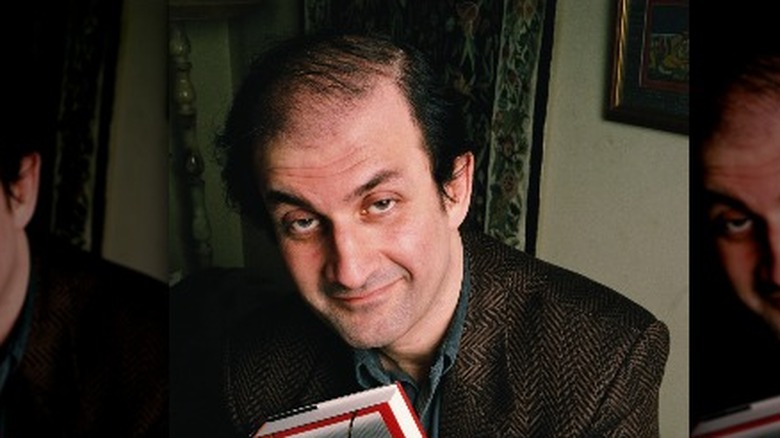

On Friday, August 12, 2022, news broke that Sir Salman Rushdie, the 75-year-old British-American author of "Midnight's Children," had been attacked onstage during an event in New York, as reported by The Guardian. Rushdie suffered life-changing injuries, having allegedly been stabbed multiple times by Hadi Matar, a 24-year-old from New Jersey who was apprehended shortly after by police, according to The Guardian. "The news is not good," said Rushdie's spokesman, shortly after the writer was taken to hospital. "Salman will likely lose one eye; the nerves in his arm were severed, and his liver was stabbed and damaged." Rushdie spent several days on a ventilator before it was announced that he was stable and looking at a lengthy recovery (via The New York Times).

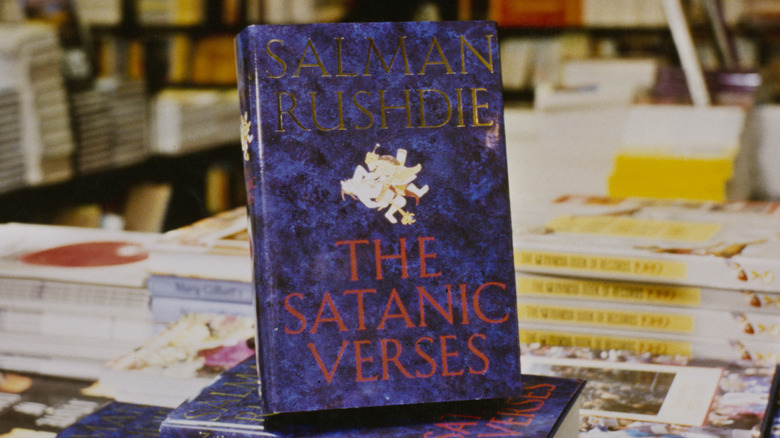

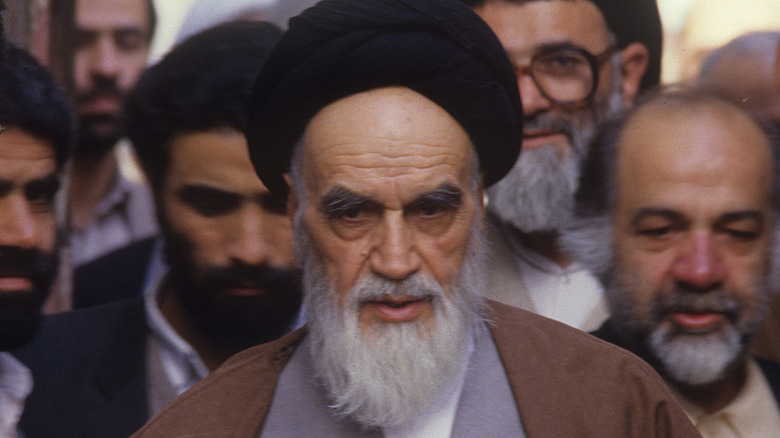

But the assault on Rushdie was not a random attack: As news outlets immediately speculated, the incident was an unexpected bloody coda to what has become known as the "Satanic Verses Affair." Published in 1988, "The Satanic Verses" was a novel by Rushdie, written in his trademark magical realism style, that caused outrage among the Muslims of numerous religious sects worldwide. Since Rushdie was born into an Indian Kashmiri Muslim family, Ayatollah Khomeini — the Supreme Leader of Iran — invoked Islamic law to declare a 'fatwa,' or death sentence, on Rushdie and his publishers. Rushdie immediately went into hiding, and the affair became one of the most significant events of the late 20th century. Here is the untold truth of the Satanic Verses.

The satanic verses were excluded from Islam

As Ohio State University's Sean W. Anthony explains in the Shii Studies Review, the phrase "the satanic verses" was coined by the 19th-century Scottish orientalist Sir William Muir. It was intended to denote a certain set of writings concerning the life of The Prophet Muhammad that were once considered canonical in the story of his life and central to the Muslim faith, but were rejected on theological grounds around 1,200 years ago. They have been considered blasphemous texts in Orthodox Islam ever since.

Per Anthony, though these verses were considered non-canonical to Muslims at the time, Western orientalists such as Muir were composing their own accounts of the life of Muhammad, and Muir et al. diverged from Islamic tradition by assuming the verses' historicity. In employing the western phrase in their title, Rushdie seemed to shine a spotlight on this divergence, while the content of the novel seemed to many Muslims to represent The Prophet in a purposefully offensive way, per Britannica.

Rushdie's title itself has been highly controversial, and in many ways enflamed the debate around the book when it was first published in 1988. The verses in question are previously canonical Islamic texts in which Muhammad is described as praising the earlier Pagan gods. As this didn't fit with later orthodoxy, they were excluded from Islam with the explanation that Satan had tricked Muhammad into uttering the verses.

The satanic verses deny Muhammad's infallibility

As described in "The Satanic Verses in Early Shi'ite Literature" (via the Shii Studies Review), the doctrine of many Islamic sects, including Shia Islam, characterizes The Prophet Muhammad as possessing "'isma," also known as infallibility or divine perfection. So why was the story of the "satanic verses" referenced by Salman Rushdie considered blasphemous and excluded from Islam? Because it seemingly described Muhammad making an unexpected error.

The story of the satanic verses differs across different sources, but per the Islamic scholar Shahab Ahmed, the essence involves The Prophet uttering a series of verses extolling the virtues of pre-Islamic polytheistic gods. As Islam is a monotheistic faith, it would appear to contradict Islamic doctrine that Muhammad would suggest other deities than Allah exist, let alone praise them.

Though versions of the tale exist in which Gabriel visits Muhammad to tell him that Satan had controlled his tongue during his utterances, many Islamic theologians have rejected the tale in its entirety, describing it as apocryphal, as described in "The Rushdie Affair: the Novel, the Ayatollah, and the West." In fictionalizing the story in "The Satanic Verses," Rushdie was accused of "reviving" a blasphemy that had been expunged from Islamic theology.

The Satanic Verses was condemned in Britain too

Days before Iran announced the fatwa against Salman Rushdie, massive and violent protests in India led to the book being banned in the country, as reported in The New York Times, and there was further violence in neighboring Pakistan. But even in Rushdie's country of residence, there were calls from politicians calling for "The Satanic Verses" to be banned.

"The Satanic Verses" hit the shelves in the U.K. in September 1988, and it wasn't long before the novel provoked widespread outrage. India and Pakistan both banned it, but that didn't stop further protests attracting tens of thousands of people in Islamabad — after which violent attacks occurred at several western political and cultural centers, and five people were killed, as reported in The Guardian.

But the Satanic Verses Affair wasn't simply a divide between the east and west: many in Britain also turned against him following the publication of the book, including several prominent British politicians. Conservative party chairman Norman Tebbitt publically described Rushdie's life as "a record of despicable acts of betrayal of his upbringing, religion, adopted home and nationality" and labeled the novelist a "villain," according to I News. Meanwhile, the Labour MP Keith Vaz marched through the city of Leicester in a protest against the book, demanding that the book be banned, and copies of the book were burned in the city of Bradford.

Rushdie's fatwa was auspiciously timed

Throughout the early months of 1989, resentment around Salman Rushdie's "The Satanic Verses" continued to simmer. Then, on February 14 of that year, Ayatollah Khomeini of Iran announced a fatwa against Salman Rushdie and the publishers of his fourth novel via a Tehran radio station, decreeing, "I inform the proud Muslim people of the world that the author of the Satanic Verses book which is against Islam, the Prophet and the Koran, and all those involved in its publication who were aware of its content, are sentenced to death. I ask all the Muslims to execute them wherever they find them," as reported by The Guardian.

As noted in The Guardian on the twentieth anniversary of the Rushdie fatwa, the timing of Khomeini's announcement was significant for the novelist and his literary circle, and not just because it coincided with Valentine's Day. This was the day that Rushdie and many other famous figures from the world of letters — such as the novelists Martin Amis and Paul Theroux — had gathered at the funeral of the travel writer Bruce Chatwin.

Chatwin's death seemed to be the end of an era for British literature. At the time, though, few of those in attendance realized that the fatwa against Rushdie was to become the overriding literary event of the years that followed. Theroux took the threat against Rushdie so lightly that he turned to him during the funeral and jokingly suggested, "Next week we'll be back here for you!"

Rushdie doubled down on his defense of The Satanic Verses

Salman Rushdie was forced to ask for police protection and go into hiding, after Ayatollah Khomeini announced the fatwa against him and his publishers. Nonetheless, the British author and his supporters were initially defiant in their response.

As noted by The Guardian, Rushdie gave two high-profile interviews shortly after going into hiding — one on British television and another on the radio. He refused to apologize and was open in his anger toward the Islamic community for entertaining Khomeini's decree. "Frankly I wish I had written a more critical book ... A religion that claims it is able to behave like this, religious leaders who are able to behave like this, and then say this is a religion which must be above any kind of whisper of criticism, that doesn't add up," Rushdie said on television.

In his radio interview, Rushdie expressed his dismay that the controversy had gotten so out of hand. However, he continued to defend "The Satanic Verses," claiming: "It's not true that this book is a blasphemy against Islam. I doubt very much that Khomeini or anyone else in Iran has read the book or more than selected extracts out of context" (via The Guardian). And the novelist may have had a point: as reporters later noted in The New Yorker, Ayatollah Khomeini never actually read "The Satanic Verses" since the novel was only available in English — a language Khomeini didn't speak, according to Professor Hamid Dabashi of Columbia University (via Al Jazeera).

Rushdie's apology was actually accepted once

Salman Rushdie's defiant tone in the face of death threats, over the publication of his novel "The Satanic Verses," was compounded in the days that followed. In one interview, recorded before he had gone into hiding, the author suggested that if people were worried that they might be offended by the book, they shouldn't read it — and that it wasn't exactly light reading material anyway. But as The Guardian notes, though Rushdie had attempted to remain combative in his first media appearances after the announcement of the fatwa, the reality of the danger that he, his family, and his colleagues now faced was growing to be undeniable.

While Rushdie was going into hiding, his wife, Mari Anne Wiggins, told The Guardian that she was "absolutely terrified" of the repercussions of Ayatollah Khomeini's words. "The Ayatollah Khomeini has issued a threat to kill my husband. The best thing for him to do now is to stay in hiding with a Special Branch man at his side," she said.

Four days after Khomeini made his announcement, Rushdie attempted to reverse the fatwa with a sincere apology to the Islamic world, saying: "I profoundly regret the distress that publication has occasioned to sincere followers of Islam." But though the Iranian government at first accepted Rushdie's reversal, Khomeini himself insisted that the fatwa itself could not be reversed, no matter what Rushdie did or said to achieve that goal.

Ayatollah Khomeini was satirized in The Satanic Verses

It is commonly accepted that the passages featuring The Prophet Muhammad — or as he is named in "The Satanic Verses," Mahmoud, — raised an uproar among many Muslims and drew accusations of blasphemy. However, as the affair rolled on, senior figures in British Islam, such as joint secretary of the Council for Mosques in Bradford, Sayed Abdul Quddus, who openly endorsed Ayatollah Khomeini's fatwa from the start, came to denounce the book in its entirety. As reported in The Guardian, Quddues claimed, "In every sentence, the whole contents of the book, is blasphemous and is full of s***."

However, it turned out that for Khomeini, there may have been another specific passage of Rushdie's book that enticed him to deliver his earthshaking fatwa. As Andrew Anthony notes in The Guardian, though Khomeini never read "The Satanic Verses" himself, select passages were read aloud to him in translation — including a passage featuring a tyrannical cleric who closely resembles Khomeini himself. Anthony reports that one British diplomat was certain that the passage in question would have "enraged" Khomeini, and likely catalyzed his rashness.

The fatwa may have been a smokescreen

Many experts believe that there was another political dimension to the fatwa that Ayatollah Khomeini put on the heads of Salman Rushdie and his publishers, after the release of Rushdie's novel "The Satanic Verses."

As outlined by Hamid Dabashi, Professor of Iranian Studies and Comparative Literature at Columbia University (via Al Jazeera), Khomeini's rule was badly corroding at the time of the Satanic Verses Affair. Though the Iraq-Iran War had finally drawn to a close, the final two years had been dominated by the revelation of the "Iran-Contra Affair," in which the country had secretly received arms from the U.S. in exchange for hostages. As described by Dabashi, issuing the fatwa can be seen as a way to allow Khomeini to create a politically useful wedge between himself and the west.

In The Conversation, political scholar Parveen Akhtar argues that Khomeini's fatwa was also a bold move to achieve dominance over other Muslim countries, including Saudi Arabia, and to position Iran — and Khomeini himself — at the center of the Islamic world. Akhtar notes that a fatwa may traditionally only be law within an Ayatollah's area of geographic control, but by decreeing that Muslims around the world should kill Rushdie, he was intentionally asserting his own global premiership.

Salman Rushdie and his supporters suffered multiple violent attacks

Many friends, associates, and readers of Salman Rushdie were left in shock and disbelief in the wake of his attempted public assassination in August 2022. As reported by the BBC, Rushdie and many others believed that he and those involved in the Satanic Verses Affair were now safe, and that the decades-old fatwa would never be followed through.

But what is often forgotten about the early years of the fatwa against Rushdie and his colleagues was that violence directed towards them did indeed take place, and not just during the public protests in the U.K., India, and Pakistan. As The L.A. Times reported at the time, as the affair was gaining steam, bookshops and publishers became targets for numerous firebombings, including two bookshops in Berkley alone.

And more horrifyingly still, the affair led to multiple assassinations, including that of Rushdie's Japanese translator, Hitoshi Igarashi, who was 44 years old when he was found stabbed to death in Tokyo in July 1991, according to The New York Times. Rushdie's Italian translator, Ettore Capriolo, had been the target of a similar attack earlier that month, but survived the attack with superficial wounds.

The fatwa was never lifted

On hearing the news that Salman Rushdie had been seriously injured in an onstage attack, the deep shock many felt was compounded by the fact that the novelist had long claimed to be safe. As New Lines Magazine describes, the author had originally traveled with a large security detail two decades prior, when he first emerged from years of hiding and began to make public appearances once more.

As noted in The Guardian, the fatwa began to recede from public consciousness partially as a result of Rushdie's own claim to have reconnected with his Islamic faith, though he later rescinded his claim and years later lived as a public atheist. Over the years, Rushdie's security grew smaller, an indicator of his confidence that the affair had been forgotten. "We live in a world where the subject changes very fast. And this is a very old subject. There are now many other things to be frightened about — and other people to kill," he said (via The Guardian).

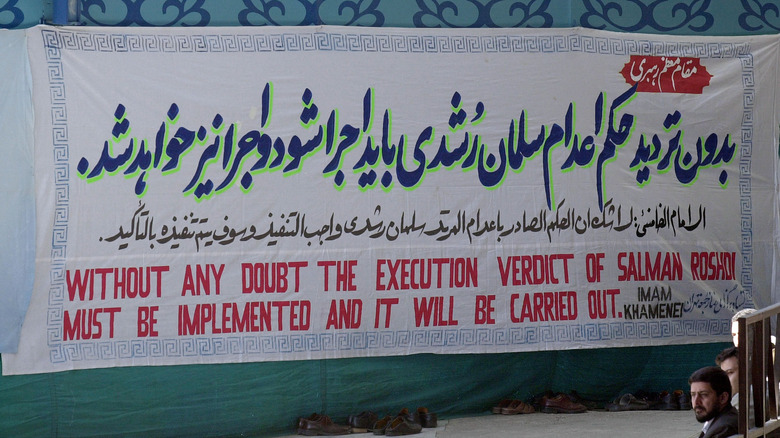

But even as Rushdie's name and the knowledge of the affair grew more obscure to the general public over the passing years, the fatwa remained in place. As New Lines Magazine notes, Rushdie's alleged attacker in the 2022 assassination attempt, Lebanese American Hadi Matar, made his Iranian sympathies clear in online posts, while Ayatollah Khomeini's successor, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, continued to invoke the fatwa as recently as 2019.

One academic calls 'The Satanic Verses' a 'love letter' to Islam

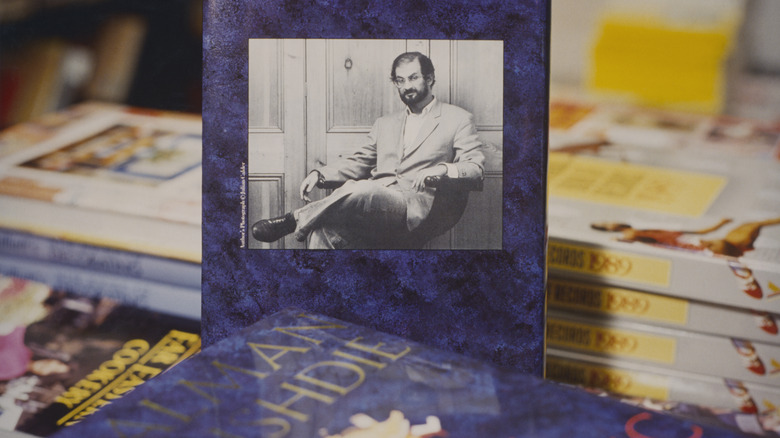

Despite continuing to cause controversy well into the 21st century, "The Satanic Verses" is not without its admirers. Held up as yet another masterpiece in the magical realism genre (per Britannica), with which Salman Rushdie's name has become synonymous in literary circles, Rushdie himself counts the book that unrooted his quietly successful life and put him at the center of an international storm over free speech as "important in my body of work as any of my other books." (via The Guardian)

But while many have assumed that the uproar caused by "The Satanic Verses" is explainable by the novel's content, other experts have questioned whether the books should be considered offensive at all — even from an Islamic standpoint.

As the literary scholar Feroza Jussawalla writes in the journal Diacritics, rather than a modern satire looking to explode religious tradition, "The Satanic Verses" may be read as a "Dastan-a-Dilruba," a traditional religious love song found in both Muslim and Hindu traditions. These love songs are typically devotional, showing the affection that the singer has for the subject, while at the same time being willing to complain about the subject of their love. Jussawalla then claims that "The Satanic Verses" is an expression of Rushdie's love of Islam in his ancestral home, India, even though the text itself sets a challenge for Islamic theology.

Rushdie justifiably claimed his attackers hadn't actually read The Satanic Verses

Just hours after Salman Rushdie had gone into hiding, the novelist gave an interview in which he questioned how many of those calling for his death, and for his novel "The Satanic Verses" to be banned, had actually read the book in question, as reported by The Guardian. In a sickly ironic twist, Rushdie's assertion that the majority of his opponents hadn't read the controversial novel would be echoed once more, in the days following the shocking assassination attempt on his life at a New York literary event in August 2022.

As the BBC reports, Hadi Matar was arrested almost immediately after his brutal knife attack on the acclaimed British novelist, who was at the event with no security detail. Still, despite a room full of witnesses, Matar pleaded not guilty to second-degree attempted murder and assault. Nevertheless, Matar gave an interview to the New York Post via phone from Chautauqua County Jail in which he outlined his motivations, describing Rushdie as "someone who attacked Islam" and expressing his respect for "the Ayatollah," calling him a "great person."

As Rushdie had suggested of his detractors decades before the 2022 attack, Matar also admitted that he had read just "two pages" of "The Satanic Verses" — which is 250,000 words long.