The Gruesome History Of The Puritan Massacre At Ulster

Following your heart is usually seen as a good thing. But in a few extreme cases in world history, it has led to mayhem and even massacres. For example, there's the legendary (and cautionary) tale of Helen of Troy, also known as "the face that launched a thousand ships," who sparked a costly war after getting kidnapped from her husband Menelaus' home and ending up in Troy with Prince Paris, per ThoughtCo.

While Helen of Troy's existence is largely relegated to myth, some real-life romantic forays have had a significant impact on geopolitics. For example, Antony and Cleopatra's union stirred the Roman Republic's last civil war, ending in the subjugation of Ptolemaic Egypt and the rise of the Roman Empire under Caesar Augustus (via History Hit). And few events have impacted British history more significantly than the decision by King Henry VIII in the 1530s to seek an annulment of his marriage to the Catholic Catherine of Aragon so he could marry her lady-in-waiting, Anne Boleyn.

The annulment led to King Henry VIII's excommunication from the Catholic Church, creating a massive rift between Catholics and Protestants in the British Isles, as reported by History. The decision would have ripple effects for centuries, contributing to everything from Blood Mary's reign to the English Civil Wars. Smackdab between these events, you'll find the gruesome Puritan massacre at Ulster in 1641. Here's everything you need to know about how this event set the stage for centuries of dysfunctional Anglo-Irish relations.

The gravest event to ever hit Ireland

Ireland has been through some serious stuff over the millennia. Dates of dread include A.D. 795 when the bearded and brutal Vikings first made landfall in the Emerald Isle, according to Irish Central. And that was fun and games compared to the plagues of 1348 and 1649, which had people dropping like flies. Of course, the frosting on the Irish history cake remains cannibalism-inducing famines (per the documentary "The Hunger: The Story of the Irish Famine," via The Irish Times) and teeth-chattering, toe-blackening winters.

These events make the pronouncement of the 19th-century historian James Anthony Froude (per Britannica) all the more startling. He declared the rebellion of 1641 to be "the gravest event in Irish history, the turning-point on which all later controversies between England and Ireland hinge" (via Irish Historical Studies).

Yet, most people haven't even heard about the events of 1641, and those who have often bring misconceptions to the table. That said, you can't really blame them. After all, both sides realized the importance of optics, spinning the events of the massacre to come out looking like the good guys. As a result, casualty figures reported from the massacre vary by tens of thousands, per the BBC. (More on this later.) While contemporary scholars tend to go with more modest figures, many English Protestants living in the immediate aftermath of the massacre selected highly exaggerated numbers. These figures were later used to justify incursions into Ireland by unwelcome visitors like Oliver Cromwell, who spearheaded the reverse-engineered massacre of 1649 in Drogheda, as reported by Irish Central.

A pre-emptive strike

In the 17th century, the Scots were a people on the move, as reported by Discover Ulster Scots. Many relocated to the Continent, settling in places you'd never imagine seeing a kilt, like Scandinavia and Poland. The New World also saw colonization efforts by the Scots in places like Nova Scotia. Some of these attempts fared better than others, and some exacerbated the ire of locals.

For example, the Irish didn't appreciate an influx of between 20,000 and 30,000 Protestant Scots starting in 1610, as reported by the BBC. Many followed the example of fellow Scots like Sir Hugh Montgomery and James Hamilton, making their homes in Ulster. As their numbers increased, so did alarm among locals. After all, the Protestant Scots (along with their English counterparts who also immigrated to the Emerald Isle) threatened to alter the religious composition of the nation.

Some scholars have suggested that the attacks in and around Ulster were a pointed response to the Scots' (as well as the English's) colonization of Ireland. They nicknamed this endeavor the Plantation of Ulster (via the BBC). Not only did these foreign Protestants represent a religious threat to the people of Ireland, but they brought a new language and strange customs. By preemptively striking the immigrants, the Irish rebels hoped to secure their religious, political, and cultural freedom once more.

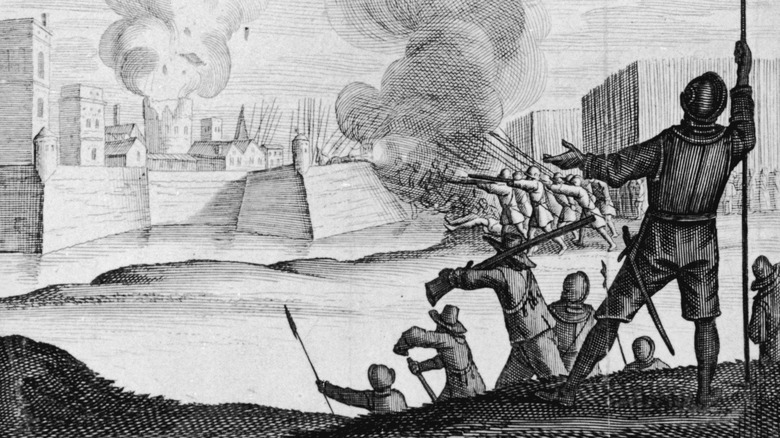

Charlemont Fort falls

The violence first erupted on October 22, 1641, when Sir Phelim O'Neill led an attack by Catholic rebels that caught pretty much everyone off guard. Shockingly, they managed to seize Charlemont Fort (via Alfred Webb's "A Compendium of Irish Biography"). According to RTÉ, O'Neill was a member of Parliament for Dungannon. He allegedly showed no mercy to his enemies, even ordering the execution of Lord Charlemont after taking the fort.

But O'Neill wasn't the only man the British Protestants had to fear. The Baron of Enniskillen, Connor Maguire, was also on the march and would attempt to lead Irish soldiers on an attack of Dublin Castle. Had Maguire proven successful, it would have represented a strategic coup for the Irish. After all, with Dublin Castle in their grips, the Irish elite would boast a weighty chip to bring to the negotiating table of King Charles I of England.

Apparently, the Irish had a snitch in their midst, however. Somebody clued local authorities in on the impending attack, and Maguire's plan was thwarted. Despite this setback, however, the spark of revolt would not be easily extinguished. The fighting became no-holds-barred, and no one, not even civilians, was spared.

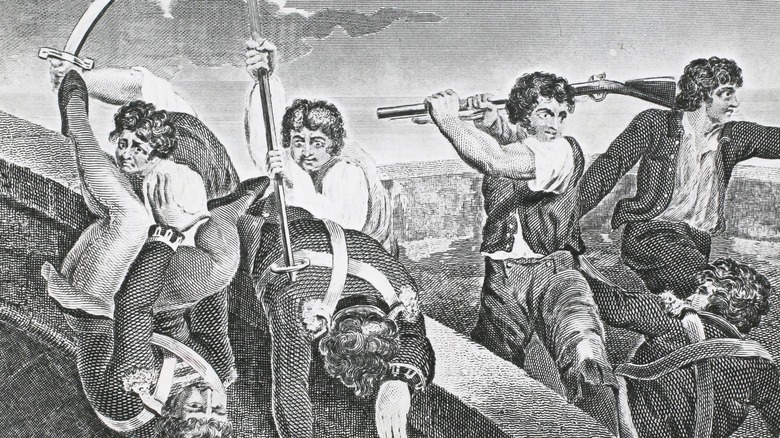

Protestant massacres swept the land

As the BBC explains, "Smoldering resentment ... contributed to the viciousness of the attacks on the Protestant settlers and the large numbers of fatalities involved." While Ulster contained the initial violence, it soon spread unchecked across the land as like-minded people got in on the action, as reported by The Guardian. As rebellion exploded across Ireland, stories of atrocities reared their ugly heads.

Scholars still debate why the rebellion turned so bloody so quickly, and one possible answer is found in the loose organization of the Irish rebels, according to RTÉ. Some have speculated that because their leaders lacked an overriding authority, their troops' actions soon broke down into heartless cruelty.

It's also important to remember that the Irish had coexisted with the British Protestants in the Emerald Isle for three decades. During this time, evidence shows plenty of exchanges took place between the two groups (via the BBC). As they say, familiarity breeds contempt, and such may have been the case as these two cultures interacted over the decades. So, when rebellion broke out, there would have been an admixture of personal and military grievances in need of redress. One thing's for sure: Things rapidly spiraled out of control.

The attempted eradication of people groups

Besides personal and military interests, Pat Muldowney's "1641 Massacres in Ulster" cites historical evidence pointing to a darker motive: genocide. Leaders encouraged the Irish rebels to eradicate all Scots, English, and Protestants from Ireland, or at the very least, send them packing. As the violence escalated, both sides resorted to barbarity, using the fog of war to blame their war crimes on the other side.

One of the most contested aspects of the history surrounding the 1641 events in Ulster remains the final casualty tally. Some Protestant writers claimed the Irish rebels massacred more than 200,000 innocent civilians, as reported by The Guardian. Interestingly, other Catholic leaders looking to rally troops also relied on inflated numbers (upward of 150,000) to make the Irish rebels' efforts look more successful.

Conor O'Mahony, an Irish Jesuit, seemed to advocate genocide by urging the rebels, "It remains for you to kill the remaining heretics or expel them from the territory of Ireland." Despite such calls for blood, most scholars today place the number killed on both sides at between 4,000 and 12,000, demonstrating just how distorted the events of 1641 became. Of course, the Irish weren't the only ones inciting carnage. Over time, English rhetoric made the Irish out to be uncivilized heathens, requiring annihilation. This is a theme Jonathan Swift would later respond to with biting satire in his work "A Modest Proposal" (via Britannica).

The perfect storm for a rebellion

The Plantation of Ulster created a tense environment, with mounting resentment against foreign colonizers, per Pat Muldowney's "1641 Massacres in Ulster." While both groups fell under the larger umbrella of Christianity, the differences between the two sects appeared insurmountable. What's more, the British settlers had relied on violence to take Ulster in the first place. Since the beginning of the Plantation of Ulster in 1610, these British Protestants represented a de facto civilian army. Through the application of the law and public execution, they'd essentially crippled local resistance, especially in Ulster. Or so they thought.

Nevertheless, Thomas Carte, author of "An History of the Life of James Duke of Ormonde," argues, Ireland's septs (or clans) still resented attempts at Anglicization, and violence simmered beneath the surface, especially among the Celtic upper crust. Raidió Teilifís Éireann (RTÉ) notes that Irish Catholics also felt inspired by the Scottish Presbyterians, or Covenanters, who revolted against England's Stuart monarchs beginning in 1638, revealing chinks in England's armor the Irish rebels hoped to exploit.

British Protestants underestimated the Irish rebels, and they would soon count this as a deadly mistake. According to Cyril Falls' "The Birth of Ulster," "There was now in all Ulster hardly a single rebel of note ... Yet in little nests of about half a dozen the shaggy, trousered outlaws still haunted the woodlands." Beginning in 1641, these so-called "shaggy rebels" showed the British colonists just how well organized and multitudinous they remained.

Total warfare dominated the land

Total war characterized the Ulster Rebellion, and abuses happened on both sides, according to RTÉ. Irish rebels terrorized local populations, with stories of pitiless violence soon emerging. Nobody was spared. The wholesale slaughter of not only military-aged men but also women, children, and the elderly became commonplace and well-chronicled in historical documents. (That said, controversy remains about how much some of these accounts got doctored to justify later Irish massacres.) Clearly, tit-for-tat ruled the day.

Some accounts speak of British Protestants stripped and drowned in freezing rivers. Even British cattle faced wholesale slaughter. Protestant Bibles were destroyed without compunction, too. But this only covers one side of the bloodletting, for the British had racked up their own list of crimes against civilians since 1610, as reported by Pat Muldowney's "1641 Massacres in Ulster." The only difference was they had the "law" and the Crown backing them.

The Plantation of Ulster brought three decades of violence and removal from the land for the native Irish. These actions contributed to searing resentments that simmered for centuries. What's more, the disruptions these colonizing efforts created led to wide-scale famine and difficulties for locals. As Muldowney points out, "The native Irish had long and bitter experience of massacre and expulsion, and had good reason to fear the rebel forces from Scotland." No doubt, this fear contributed to the 1641 Catholic uprising.

The 1641 Depositions

At this point, you may be wondering how much evidence could possibly remain from a war fought hundreds of years ago. But, surprisingly, a vast storehouse of historical records followed the initial massacre, as reported by RTÉ. All told, roughly 8,000 eyewitnesses to the events in Ulster fled to Dublin, testifying about what happened.

Known collectively as the 1641 Depositions, they provide valuable insights into the events in Ulster and other parts of the nation, according to Trinity College Dublin. Of course, these documents also have their shortcomings. Apart from the illegibility of the handwriting and the ancient linguistics (click an original to see for yourself), their accuracy remains contested. After all, the individuals who created them had no benefit of hindsight, speaking about observations still colored by trauma and horror. What's more, optics remained something these British Protestants proved very conscious of. To top it off, few depositions came from the Catholic rebels.

Professor Jane Ohlmeyer is an expert on the depositions, and she notes, "The bloodletting was on both sides but Oliver Cromwell used this as justification for his [massacres at] Drogheda and Wexford" (via The Guardian). Even with all this one-sidedness, however, the depositions are the best we've got when it comes to understanding what the civilian experience of the massacre and its aftermath looked like. Because of the subject matter, the picture painted is naturally grim and tragic.

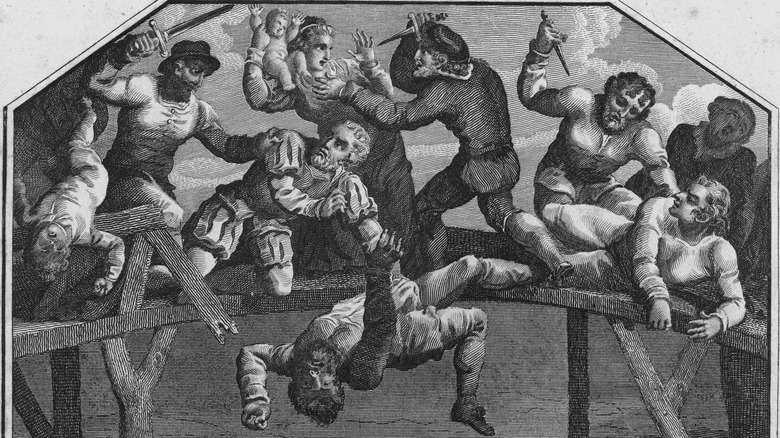

The event that spawned a ghost story

One of the most infamous events of 1641 led to a famous ghost story, per RTÉ. The atrocity involved the drowning of approximately 100 men, women, and children in the River Bann near Portadown (via The Irish Times). What makes the event especially pitiable is that it occurred during one of the coldest periods on record. Yet, locals showed no mercy in stripping the Protestants of their clothing, imprisoning them overnight in a barn, and throwing them to their deaths in the river the following day.

The events surrounding this horror have been pieced together from accounts in the 1641 Depositions. Among the most famous of these testimonies comes from Elizabeth Price, whose children died in the drowning. After imprisonment by Irish-speaking rebels and weeks of torture, Price claims she and her children were offered a safe return to England. We don't know why she didn't go, but she sent her children, inadvertently, to their deaths.

Price later visited the site of the Portadown Massacre and claimed to see a phantom. She recalled, "A vision or spirit assuming the shape of a woman waist high upright in the water naked with elevated and closed hands." Price noted the white skin and hair of the woman and that she chanted the word "revenge" repeatedly. While researchers point to Price's obvious trauma, Protestant propagandists wove the tale into a ghost story and call for divine retribution.

The rebellion lasted for a decade

Although many works on the Puritan Massacre at Ulster tend to focus on the initial events in 1641, it's important to remember that the rebellion actually lasted for a decade, as reported by the BBC. Over time, the violence gained new strength with the addition of English Catholics. According to Oxford Reference, the theater of war remained confounding, with the Irish confederates fighting against an army of Scots sent to shield the Ulster Protestants. But they also waged war against parliamentarians and royalists.

Over time, Irish Catholic forces re-organized into the Confederate Catholics of Ireland, appointing military veterans like Owen Roe O'Neill to train the soldiers (per RTÉ). In 1646, this training paid off big-time. The Irish Catholic confederates enjoyed an astounding victory at the battle of Benburb led by O'Neill. During the battle, they laid waste to the main Protestant army. (No exaggeration.)

You could say, everything appeared to be going right for the Irish rebels. But when it mattered most, the confederates failed to put the final nail in the Plantation of Ulster's coffin. Exacerbating this lack of resolve were problems within the confederate ranks. As it turned out, the cultural divide between the Irish and English Catholics proved greater than the unifying factor of religion (via the BBC).

A boomerang effect

According to RTÉ, the events of 1641 would be politicized and exploited by Oliver Cromwell of England to justify his army's barbarous actions in Ireland beginning in 1649. The blood-letting employed by Cromwell's army remains legendary. Nevertheless, the focus remained on 1641. Rabble-rousing accounts of the horrors perpetuated against the British Protestants always appeared when most politically useful in the larger English, Scots, and Irish conflict.

A select group of testimonies from the 1641 Depositions was also used to raise the temperatures of British blood. For their part, the Irish denied the depositions' accuracy, dismissing them out of hand. Neither response proved helpful when it came to a full understanding of what had occurred and why. Instead of closure, more conflict followed.

What's more, artful retelling of the events during the massacre had an unforeseen impact on the British Protestants who remained in Ireland, per Irish Central. Historian Micheal O Siochru explains, "The massacre of Protestants helped shape Protestant identity in Ireland, the sense of being under siege, of being the victims of Catholic aggression." They were also used to justify Cromwell's efforts in Ireland to make the Irish pay for the Puritan Massacre of Ulster. Paybacks came with egregious indifference to the suffering of civilians at battles like the Siege of Drogheda.