The Story Of The First Recorded Murder Trial In America

In 1799, Levi Weeks, a carpenter in New York City who aspired to be an architect, met a young lady by the name of Gulielma Sands, who had just moved into the city to work for her cousin, Catherine Ring. Catherine and her husband, Elias, owned a millinery business, and Sands lived in the Rings' boarding house whilst she worked for them. Weeks, who was also a resident at the boarding house, began an affair with Sands, and the two were caught having a sexual relationship multiple times, according to Biography.

On December 22, 1799, Sands planned to secretly elope with her new lover and told her cousin, Hope Sands, who was also a resident at the Rings' boarding house, that she was engaged to Weeks. Sands and Weeks both left their rooms that evening, but Sands never returned. An investigation quickly occurred to find Sands' location, and when Weeks was questioned on his involvement, he pled ignorance and claimed that he and Sands were never engaged. Thus began the United States' first recorded murder trial in the newly-born nation's history (via Biography).

Lawyer up

Catherine and Elias Ring were unconvinced of Levi Weeks' alibi, and so they began telling reporters details of the murder. A few days after the murder, a little boy found a piece of clothing belonging to Gulielma Sands. It was on January 2, 1800, when Sands' body was finally found, inside the Manhattan Well, according to the Historical Society of the New York Courts. Sands' body was brought to the Rings' boarding house, where it was left for viewing for three days, according to Biography.

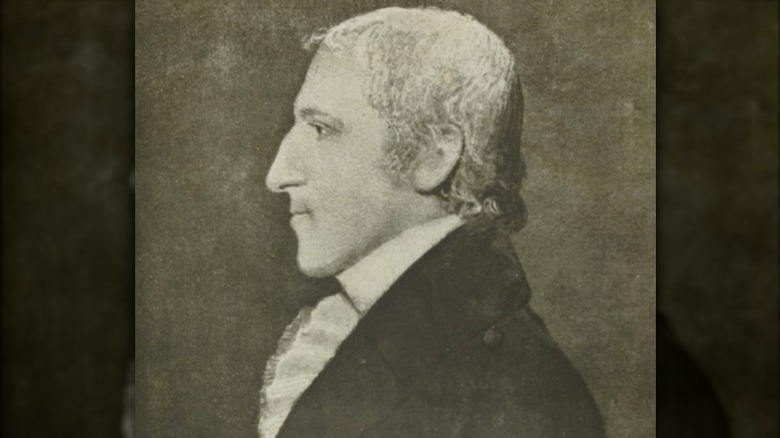

As details of the murder unfolded and became public, the court of public opinion declared Weeks a guilty man. However, Weeks had a trick up his sleeve to escape accusations of his alleged crime, and that was to utilize his connections. Even though Weeks himself wasn't very notable, he had a successful and wealthy brother, Ezra Weeks. Ezra Weeks was an architect who knew some of the nation's most powerful men and was able to get Alexander Hamilton and Aaron Burr, two well-known political rivals, to represent his brother in the case (via Biography). However, Hamilton and Burr didn't have much experience with criminal law, so they employed the help of another Founding Father, Henry Brockholst Livingston (above), according to Biography.

Foes to allies

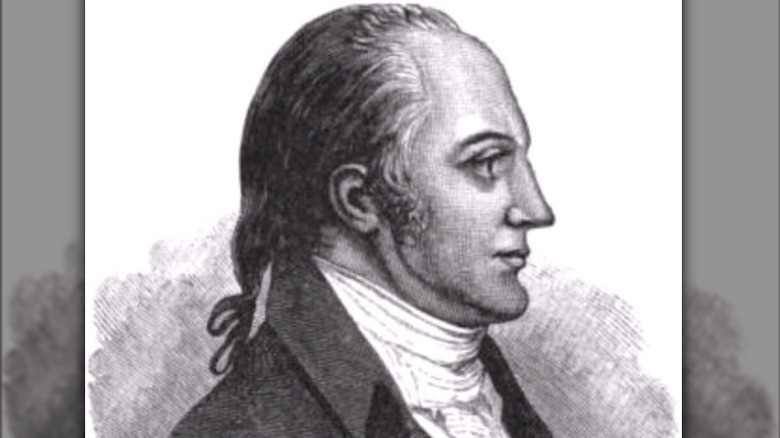

The fact that Alexander Hamilton and Aaron Burr worked together on a legal case, let alone a criminal one, was odd for the time. The two despised one another and had a rivalry that went back to 1791, after Hamilton won a seat for the U.S. Senate that Burr's father-in-law had been running for, according to Britannica. Hamilton and Burr had different opposing ideologies, and subsequently fought for two separate political parties; Hamilton supported the Federalist Party, and Burr supported the Democratic-Republican Party (via Biography).

The Federalist party believed in a strong central government. As the first Secretary of the Treasury, Hamilton helped steer the United States economy to a more business- and manufacturer-friendly nation. The Democratic-Republicans, on the other hand, were a political faction created by Thomas Jefferson and Aaron Burr, who upheld states' rights and believed the nation should be an agrarian-based society, according to Biography. These major disagreements in politics caused disdain between Burr (above) and Hamilton, although, being professionals, they had worked together before on a handful of cases — none of them, however, criminal.

The trial

Given the notoriety of the trial, and the public's hatred for Levi Weeks, the defense team had an uphill battle to fight if they were to get their client off the hook. The prosecution made the case that Weeks had seduced Gulielma Sands, and told Sands that he wanted to marry her in secret as part of a plan to murder her, according to Biography. The prosecution's main witness, a man named Richard Croucher, claimed to have witnessed Sands and Weeks having a sexual relationship, helping the prosecution's case. The team also proposed that Sands had been pregnant and that this encouraged Weeks to murder her (via Biography).

Hamilton and Burr focused on the details of the prosecution's case as a way to sow doubt with the public. The defense team proved that Sands was not pregnant, and they also attacked Croucher personally, accusing him of having his own affair with Sands, according to E Link. The defense team also brought a witness to the stand who claimed he saw Croucher near the Manhattan Well the night of Sands' murder. In a theatrical manner, the defense then had two candles lit in front of Croucher's face, whereupon Hamilton (or possibly Burr; accounts vary) told the jury to "Mark every muscle of his face! Every motion of his eye! I conjure you to look through that man's countenance to his conscious" (via E Link).

The aftermath

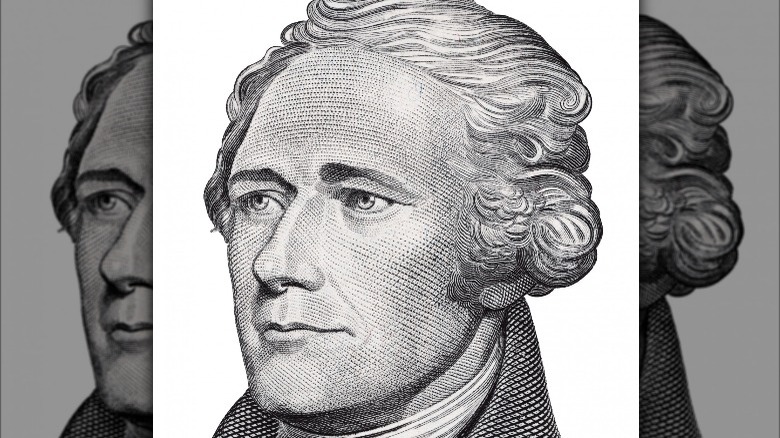

After 44 hours of a consecutive trial in an era where most trials lasted only a day, the prosecution had grown exhausted. It's reported that a prosecutor fell asleep during the final hours of the trial, and therefore couldn't provide a closing argument, according to E Link. The defense team, on the other hand, was so confident in their case that Hamilton (above) declined giving a closing argument. After five minutes of deliberation, the jury declared Levi Weeks not guilty, and he was released, according to Biography.

The public still held Weeks in a negative light, and so he was forced to move to Mississippi, where he pursued his career as an architect and found success. Though the real killer of Gulielma Sands was never found, Richard Croucher, who the defense team painted as the real criminal, became involved in a series of other crimes. Croucher was arrested for raping his teenage stepdaughter but was pardoned due to mental health reasons, according to Biography. He also moved back to England, where eventually he was executed for a crime that's lost to history (via Biography).

If you or anyone you know has been a victim of sexual assault, help is available. Visit the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network website or contact RAINN's National Helpline at 1-800-656-HOPE (4673).

A rivalry ends

Later on that year, Aaron Burr ran as Thomas Jefferson's running mate, and almost became president himself, given the way elections functioned back then. Instead of a party ticket running together, the candidate with the most electoral votes became president, and the second-place candidate became vice president. In the election of 1800, Jefferson and Burr tied, so Burr tried to take a shot at actually becoming president himself over Jefferson. However, Alexander Hamilton encouraged members of the Federalist Party to vote for Jefferson over Burr, and Jefferson won the election (via U.S. History).

Four years later, in 1804, Aaron Burr famously challenged Alexander Hamilton to a duel to settle their rivalry once and for all. Burr and Hamilton both took shots at each other, with Hamilton missing his and Burr mortally wounding Hamilton. Some 36 hours after the duel, Hamilton died in his home, and Burr was ostracized and was seen as a murderer, according to History. Given how much these two men hated each other, to the point of death even, it is ever more surprising that they worked together on the case of an ordinary carpenter in a relatively ordinary crime, which subsequently became such a high-profile case. The two rivals managed to work together to achieve an acquittal in the first recorded murder trial in the United States.