The Tragic Real-Life Story Of Aaron Burr

History usually comes to us in abridged form. The story of the world and mankind comprises millions of years and people, after all. No one can possibly deep-dive into every single facet of what has gone before.

As a result, sometimes a shallow thumbnail portrait of a historical figure gets stuck in the public consciousness. When most of us think of Benedict Arnold, all we know is that he was a traitor. When we think of George Washington, all we know is that he was the first president. And when we think of Aaron Burr, all we know is that he killed Alexander Hamilton in a duel.

If you've seen the musical Hamilton, you might also know that Burr was Hamilton's lifelong frenemy who disdained Hamilton's immigrant and illegitimate status. But Aaron Burr had a story in his own right — he was an immensely talented man who served his country tirelessly. He also suffered incredible loss over the course of his life and was never able to shake off the infamy he gained when he killed Hamilton. The tragic real-life story of Aaron Burr has been overshadowed by his more famous and more sympathetic compatriots — especially, in a fitting twist, Hamilton.

Aaron Burr was an orphan

Thanks to Lin-Manuel Miranda's incredible play, everyone knows that Alexander Hamilton was an illegitimate child, and if you're paying close attention to the lyrics, you'll know that Aaron Burr was also an orphan. In many ways, Burr's story is even more tragic because he went from a stable family life to orphan status in a whirlwind of tragedy over the course of a about a year.

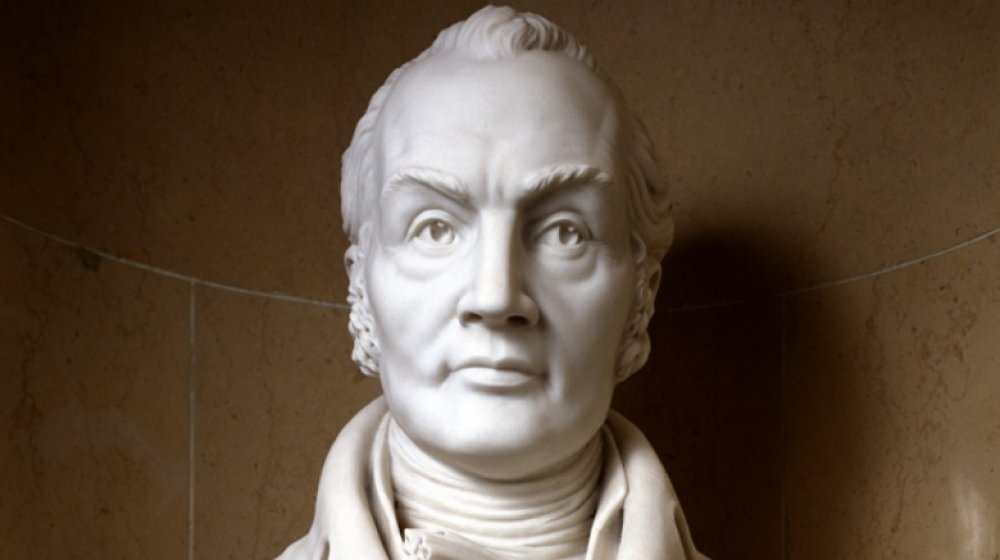

As noted by Encyclopedia Britannica, Burr's parents and grandparents all died within a few years of his birth in 1756, a tragic sequence of events that left him an orphan at age two. In 1757, shortly after Burr's birth, his father (pictured above) traveled to Massachusetts to give a speech. He became ill with a fever and died shortly afterward. Burr's grandfather, Jonathan Edwards, took over his son-in-law's position at Princeton (then known as the College of New Jersey). Edwards decided to be inoculated against smallpox and died as a result of complications a few months later in March 1758. A month later, Aaron's mother passed away of smallpox as well. Five months after that, his grandmother Sarah died of dysentery. (The 18th century was not a great time for anyone hoping to live a long life.) This storm of loss left Burr and his sister, Sarah (also called "Sally"), to be raised by their uncle, Timothy.

Burr's uncle was abusive

Aaron Burr lost his parents and grandparents to disease when he was just two years old. He and his sister, Sarah, were taken in by his uncle, Timothy Edwards, and his wife, Rhoda.

On the surface, Uncle Timothy did well by his niece and nephew, seeing to their education and care. But Timothy was an extremely puritanical man who believed that harsh discipline was the only way to ensure that children matured properly. The adult Burr didn't speak much of his childhood, and the few times he did, it was to paint a less than pretty picture. According to Arnold Rogow, Burr once said that Timothy often lectured and beat him "like a sack."

This prompted Burr to run away from home on several occasions — the earliest being when he was just four years old. He was missing for several days. When he was ten, Burr ran away from his abusive uncle again, attempting to sign on as a cabin boy for a sea voyage. Timothy got word of the scheme and raced to the docks, at which point Burr fled up onto the mast of the ship and refused to come down until his uncle promised not to punish him.

Aaron Burr's daughter died very young

Aaron Burr married his first wife, Theodosia, in 1782 when he was 24 years old. Their first child, also named Theodosia, was born in 1783 and grew up to be the apple of Burr's eye. But a second daughter almost supplanted her. Named Sarah and called Sally after Burr's sister, their second daughter was born in 1785 and was apparently a beautiful and well-loved child, though little is known about her.

Sadly, Sally only lived for three years. According to Find a Grave, the little girl was healthy at first but then began to "fade." Author Edward T. James confirms that Sally only lived three years in Theodosia's entry in Notable American Women.

The Burrs' grief over the loss of their young daughter is obvious from their letters at the time. Burr's wife wrote, "Variegated have been my scenes of anguish, but this exceeds them all. [...] All aid proved vain — she passed gently from me to the region of bliss ... yes, my Sally, she is ... gone." For Burr's part, he became focused solely on his surviving daughter, Theodosia, upon whom he "lavished his love and attention," at the expense of the stepchildren he gained when he remarried later in life.

Aaron Burr's first wife died of stomach cancer

Aaron Burr met his first wife in 1778, when he was in his early twenties. Theodosia Bartow Prevost was ten years older than Burr and was already married — to a British army officer named Jacques Marcus Prevost. Wanting to support the revolution, she opened her home to officers of the Continental Army.

Burr began visiting Theodosia so often that gossip began to circulate that their relationship was not entirely innocent. With Theodosia's husband away, the two slowly gave up any pretense, and according to author Nancy Isenberg, Aaron and Theodosia were openly in a relationship by 1780, apparently unconcerned about the scandal. When Prevost died of yellow fever while in Jamaica the next year, Burr and Theodosia were finally free to be married. They did so in 1782.

The Burrs were very much devoted to each other, but Theodosia was never a strong woman and was regularly ill throughout their entire relationship. She began experiencing severe pain in the early 1790s and died of stomach cancer in 1794 at the age of 47. Burr was broken by the tragic loss. As the New York Daily News reports, he wrote that Theodosia was "the best woman and finest lady I have ever known."

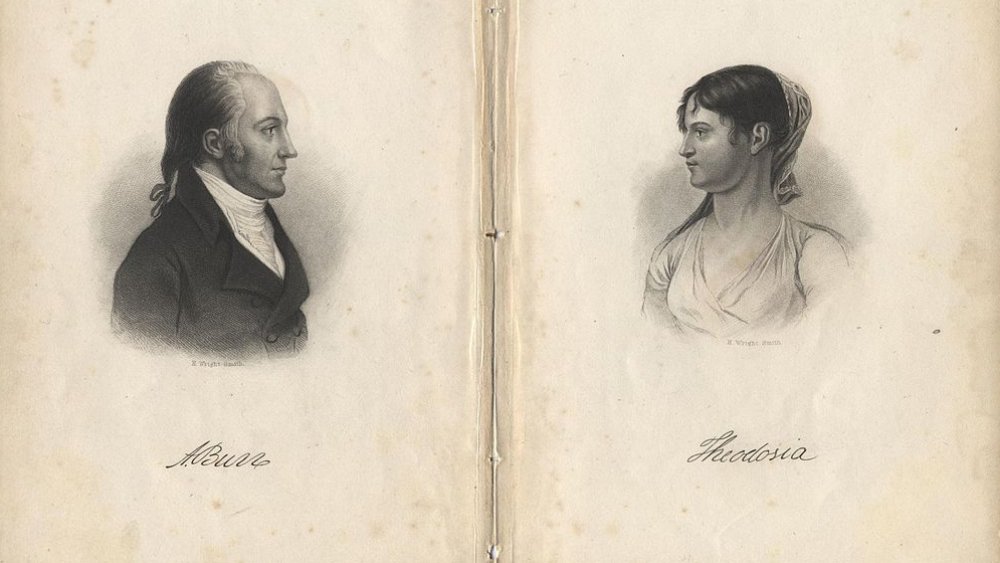

Aaron Burr's daughter was lost at sea

After the deaths of his youngest daughter, Sally, and his wife, Aaron Burr focused his affection on his eldest daughter, Theodosia. As Atlas Obscura writes, Burr doted on his daughter and offered her a breadth of education that was unusually progressive for women at the time. At one point, he wrote of his hopes for his beautiful daughter, saying, "I hope yet by her to convince the world what neither sex seems to believe — that women have soul!"

Theodosia was indeed very intelligent and very accomplished. She eventually married and had a son — but the birth was very difficult, and Theodosia suffered continuous health issues afterward. When her son died of malaria at age ten, she sank into a terrible depression. Longing to see her father, she boarded a boat headed for New York in 1812. She was never seen again — in fact, the ship she was on, the Patriot, disappeared entirely.

As the Wilmington Star-News reports, there are many theories as to her fate. It might have simply been the terrible storms that battered the coast that year — a painting that many believe depicts Theodosia was found in North Carolina in the 1860s, which supports the theory that the ship sank. But some believe that pirates took the ship and killed Burr's daughter, making her "walk the plank."

Burr tried -- and failed -- to start his own country

Alexander Hamilton's death in 1804 after his duel with Aaron Burr was shocking at the time. Duels were fading from polite society — Burr and Hamilton had to travel to the wilds of New Jersey because dueling was illegal in both New York and New Jersey. And many suspected that Burr had dishonorably killed Hamilton intentionally.

Whether Burr murdered Hamilton or intended to wound him and miscalculated, he found himself a social and political pariah in the wake of the duel. Going broke and with few doors left open to him in the country he'd helped to found, Burr hit upon a scheme that would have set him up as not just a president — but an emperor.

As PBS reports, the idea was to gather up a small but effective army and lead the Louisiana Territory to independence. The borders of the territory were disputed by Spain, and the people living there weren't eager to be either Spanish or American. Burr thought he might set himself up as their leader. He initially made quick progress, recruiting General James Wilkinson — named governor of Northern Louisiana – to be his partner. But Burr's plans became publicly known, and he failed to gain any support from Spain or Britain. Wilkinson got cold feet, and the whole scheme collapsed. Instead of becoming Emperor Aaron I of a new country, Burr was eventually arrested and charged with treason.

Aaron Burr was tried as a traitor

Aaron Burr made two big mistakes in his life. The first was killing Alexander Hamilton in their famous duel, an act that left him a pariah in both political and social circles. The other was crossing Thomas Jefferson.

As Smithsonian Magazine writes, back in 1800, when Jefferson ran for president alongside Burr, there was no distinction between electoral votes for president or vice president. When Burr and Jefferson wound up tied, Burr could have conceded to Jefferson and become vice president as planned. Instead, he insisted the election go to the House of Representatives, which took 37 votes to finally elect Jefferson. As Smithsonian also reports, Jefferson was not amused. He booted Burr from the ticket in 1804.

After that, Burr tried a fantastic scheme to create a whole new country for himself out of the Louisiana Territory. When things fell apart, Jefferson made sure that Burr was charged and tried for treason, despite having very little evidence that Burr had ever actually attacked the United States itself. Despite the weakness of the evidence, Jefferson pushed Supreme Court chief justice John Marshall to convict. Marshall, who hated Jefferson, refused to give in, and Burr was eventually acquitted. It didn't matter — whatever was left of Burr's reputation had been destroyed, and he would never recover politically or financially.

Aaron Burr had a secret second family

Aaron Burr doesn't enjoy the best reputation. Despite his very real achievements during the Revolutionary period and the first two decades of this country's existence, most people remember him mainly for having killed Alexander Hamilton in a duel. A little more digging usually doesn't improve things for Burr, who was also tried for treason and ended his life in ignominy and shame.

What few people, even Burr's detractors, know is that he had a secret second family with a Black woman. As The Washington Post reports, Mary Emmons was a servant working the household of Jacques Marcus Prevost and Burr's future wife Theodosia Bartow Prevost. When Jacques died and Theodosia married Burr, she took Mary with her to her new home in New York. Burr likely had at least two children with Mary: Louisa Charlotte and John Pierre (pictured above).

While there's no firm evidence that Louisa and John were Burr's children, it seems very likely. Burr allowed Mary and the children to live in his house in Philadelphia while he stayed with Theodosia in New York. Burr also purchased land for John Pierre to build a house on, and genetic tests indicate a strong likelihood that his descendants are related to Burr.

Aaron Burr never meant to kill Alexander Hamilton

Aaron Burr is known mainly for killing Alexander Hamilton in a duel — an act that ruined him politically and marked him as a villain for all time. Burr is often depicted as the resentful rival of the great Hamilton, so blinded by anger that he kills his former friend over some mild insults.

The truth is more complex. For one, as Den of Geek recounts, Hamilton's campaign against Burr was more than just a few insults. Hamilton worked directly against Burr's ambitions for years. Hamilton's influence likely cost Burr crucial votes in the presidential election of 1800 and almost certainly cost him the governorship of New York in 1804. With his own political party soured on him, the loss of the governor's mansion left Burr without any sort of power base. His political career was over, and Hamilton was to blame.

More importantly, as Time notes, Burr almost certainly did not intend to kill Hamilton. Following the rules of dueling, Hamilton chose the weapons, and without telling Burr, he chose pistols with hair triggers that were also wildly inaccurate. Duels rarely ended in death under normal circumstances, and Burr was patient and calm throughout theirs. The chances that he meant to either throw away his shot or simply wound Hamilton are very high. In fact, Hamilton should have survived his wound — but the bullet ricocheted off a bone, allowing it to do more damage than it otherwise would have.

Aaron Burr died broke and ruined

You might think that a hero of the Revolutionary War and former vice president of the United States would have lived a life of quiet respect in his later years. But Aaron Burr ruined his reputation with a few minor missteps, like killing Alexander Hamilton and attempting to found his own country by stealing an entire territory from the United States through armed force. The fact that he was kind of incompetent about this last part didn't help his reputation, either — and neither did the trial for treason that stemmed from this attempt.

In fact, as Oprah Magazine reports, after his acquittal on charges of treason, Burr had to leave the country entirely for several years. He was persona non grata in society, his political party had disowned him, and there was simply no way for him to live. He did eventually return to New York, where he practiced law in obscurity.

Burr's finances grew desperate, and in 1829, he petitioned the government to grant him a military pension – and fought for five years to get it. The man who once had ambitions to be president was even reduced to marrying a wealthy widow in order to get money for some investment schemes. As author Nancy Isenberg writes, Burr's divorce from Eliza Jumel was a messy affair, with Jumel basically accusing him of marrying her simply to steal her fortune.

Aaron Burr had a series of strokes

Aaron Burr was a war hero – as his official Senate biography notes, his friends and admirers called him "Colonel Burr" in honor of his Revolutionary War service. But his efforts in the service of his country took a toll on his health. He resigned his commission in 1779 due to failing health, and it took him several years to recover.

Burr lived to be 80 years old, but toward the end of his life, his health once again failed him. As Gerard T. Koeppel notes, Burr suffered a massive stroke in 1834 that left him partially paralyzed. When he was moved to Staten Island so that a cousin could look after him as his condition worsened, he had to be carried in his bed through the streets of New York because he was unable to get out of it.

As Oprah Magazine makes clear, Burr was a shadow of the man he'd once been. He was broke and financially dependent on the charity of his friends, and he suffered several more strokes as he became increasingly debilitated. The man who'd once had ambitions to lead the country he helped to create finally died on September 14, 1836, lonely and bedridden. (Burr's death mask is pictured above.)

Burr got divorced the day he died

As author Nancy Isenberg notes, when Aaron Burr died after a series of debilitating strokes in 1836, he'd spent the previous two years of his life fighting a vicious divorce from his second wife, Eliza Jumel.

Jumel, almost 30 years younger, had come to New York as a young woman and worked as a domestic servant and possibly an actress (at a time when being an actress was often considered little different from being a prostitute). She married a wealthy merchant, and when she met Aaron Burr, she was one of the richest women in New York. Jumel was an ambitious social climber, and many speculate that she married Burr in order to burnish her reputation, while Burr likely married her for access to her considerable fortune.

As anyone could have predicted, the marriage didn't last. After just four months of marriage, they separated, and Eliza sued for divorce, which Burr contested. According to Rick Beyer, Jumel made the divorce particularly painful for Burr by hiring Alexander Hamilton Jr. as her attorney in the matter — thus granting Hamilton Sr. some small measure of revenge from beyond the grave. The court granted Jumel's request on September 14, 1836 — the very day that Burr died on Staten Island.