The Curious Coronation Of Charles I Explained

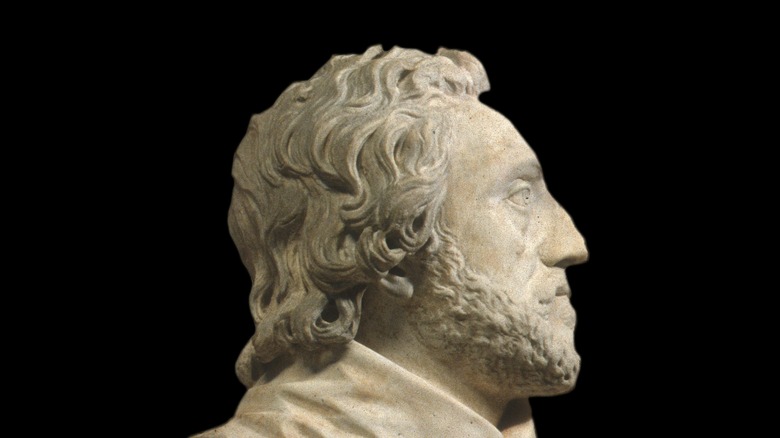

Charles I, king of England, Scotland, and Ireland, was the second of the famous British Stuart kings. He was known as a patron of the arts and, according to Britannica, was sincerely devout, courteous, and not a little shy. But what most people associate with this king is his death by beheading in 1649: Charles I has the ignominy of being the only British monarch to be executed for treason. This was an outcome of the English Civil Wars, which pitted parliamentary forces against monarchial. People have been debating about Charles I ever since: As Historic Royal Palaces points out, despite being an exemplary person, he was just a poor monarch.

He also had one of the most curious coronations in British history. Coronations are usually rote, elaborate, ceremonial affairs that officially invest the power of the monarchy to a queen or king. But in the case of Charles I, it was different since it seemed to presage all of his future problems, such as conflicts between Catholics and Protestants, as well as reflect his own tone-deafness to politics and the people. The coronation of Charles I ultimately offers a window into how the monarchs of Britain were viewed, how they viewed themselves, and how they lost power — and in Charles' case, his head.

He shouldn't have been coronated in the first place

In truth, Charles I was not destined to be king. He was born in 1600 to King James I. According to Britannica, James was initially James VI of Scotland, who then, upon the death of Elizabeth I — who had no direct heirs — became King of England. This unified the two kingdoms of Scotland and England.

Charles was prone to illness as a child and stayed behind in Scotland for a time, before moving to England to join his father's court. Yet it wasn't his ill-health that would have prevented a coronation, it was the fact that he had an older brother, Henry Frederick (born 1594). Westminster Abbey tells us that Henry Frederick was made Prince of Wales in 1610, thus making him the presumptive heir.

However, Henry Frederick's ascendancy was not to be. On November 6, 1612, the prince died, likely of typhoid fever, putting Charles next in line. By then, Charles had already shown a taste for courtly elegance and a love of the monarchy. According to Royal Families, he was entranced by the arts and spent much on them. He also had a deep set belief in the absolutism of the monarchy, which, in combination with his poor political skills and lack of charisma, would lead to eventual trouble. Upon the death of his father in 1625, Charles was ready for the throne and wanted to have a perfect coronation.

He was coronated in Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey was the venue for Charles' coronation on February 2, 1626. According to History.com, coronations have been taking place at Westminster since 1066, starting with William the Conqueror. In fact, to the present day, all but two British monarchs (Edward V and Edward VIII) have been crowned at Westminster.

Originally founded by Benedictine monks, Westminster Abbey was expanded in 1040 by King Edward I, also known to history as King Edward the Confessor. It was there that a large cathedral was commissioned, St. Peter's Cathedral, which was dubbed "West-minster." This was meant to differentiate it from "East-minster," which was St. Paul's Cathedral.

By the time of Charles' crowning, Westminster had already developed a long tradition of coronations. Yet it should be noted that the physical Westminster Abbey that Charles was crowned in was not the same as the one where William the Conqueror was anointed. In the mid-12th century, the original Westminster was torn down and a Gothic-style cathedral was built, dedicated in 1269. It was in this version of Westminster that almost every British monarch to the present day has been coronated.

He decided to go for the vernacular

Coronation ceremonies are decidedly elaborate affairs. Katie Whitaker's "A Royal Passion: The Turbulent Marriage of Charles I of England and Henrietta Maria of France" describes how Charles I formed a committee of bishops and peers to plan his special day. These luminaries prepared an order for the coronation, which mimicked coronations going back to the medieval period. Charles even previewed it by trying on the old Saxon vestments. However, there was one difference — Charles I's coronation would be using the language of the common people, English, instead of Latin.

"Music and Ceremonial at British Coronations" explains how Charles' father, James I, had established this vernacular tradition at his own coronation in 1603. That version was an Anglican ceremony that offered translations of texts into English, although some Latin vestiges remained, such as the Litany. James's oath was also conducted in Latin, English, and French. It seems that Charles wanted to follow this tradition, which was a signal of how the Anglican Church was moving away from Catholicism.

The coronation ceremony featured a sermon about death

British coronation ceremonies are infused with religion, and Charles I's was no exception. To start, the coronation date needed to have holy significance. For his coronation, the king-to-be picked February 2, 1626. While today we may associate this date with rodents seeing shadows and Bill Murray movies, in the 17th century, more people would think of it as the holy day of Candlemas. "Images of Kingship: Charles I, Accession Sermons, and the Theory of Divine Right" explains that this held special religious significance for the people. Charles wanted to emphasize the solemnity of the occasion and his right as a divinely appointed monarch.

One source from the period, "A Succinct Account of the Coronation of Charles the First," tells us that the king, aside from entering Westminster Abbey with a procession of retainers, was accompanied by bishops who then approached a throne where William Laud, the archbishop of Canterbury, William Laud, stood by.

A sermon and general acclamation were made by Bishop Richard Senhouse, who, according to "Charles I and the People of England," chose from the Book of Revelation with the intent of preparing Charles for the rigors of rule. One attendee later remarked that the sermon seemed "to put the new king in mind of his death than his duty in government."

The coronation ceremony was political

The ceremony was as political as it was religious: Almost every choice at the coronation ceremony was a political one. "Charles I and the People of England" describes how the king's oath was administered by the archbishop, who asked a series of four questions. These oaths, while they promised to protect the people, the clergy, and their rights, were seen not as a social contract with the people, but rather a vow between Charles and God. This was in part to emphasize his absolute power. One subtle but important example of this is the last question in which the archbishop asked Charles, "Sir, will you grant to hold and keep, the Laws and Rightful Customs, which the Commonalty of this your Kingdom have ..." In older versions, the word "chosen" appeared at the end. This was omitted, much to the dismay of those who backed a more representative form of government in Parliament.

Another example of politics was how knighthoods were typically given at coronations. "Archaeologia" tells us that Charles was highly resistant to following the traditions of his father, who had appeared to have created a great many knights during his reign. Nonetheless, "The Personal Rule of Charles I" tells us that the king had no qualms about later laying fees on those knights who did not attend the ceremony, on the grounds that it constituted a royal summons. After all, Charles was a lavish spender on his art collection and was having trouble raising money through Parliament.

He scandalously wore white

One very specific choice that King Charles I made at his coronation was what to wear. "A Succinct Account of the Coronation of Charles the First" tells us that the king was "cloathed in white Sattin." This is significant since, according to "The History, Principles and Practice of Symbolism in Christian Art," the monarchs had traditionally been cloaked in purple at coronations. For his fashion sensibilities, Charles was dubbed the "White King."

Why white and not purple? A common view is that the king wanted to emphasize the holiness of the occasion and also emphasize his own moral purity. A more recent explanation is offered by Leanda de Lisle in her book, "The White King." She claims that his father, James I, had also done so, and Charles was just following his example. Regardless, the choice of white seems to have strong significance for Charles in carrying on the tradition of his father and to emphasize his own character.

The choice of white was also controversial since it recalled the folklore of a white-clad prince who lost the love of his people. This ill-omen is related by "The History, Principles and Practice of Symbolism in Christian Art," which notes a prophecy attributed to the mythical Merlin, who foretold that the coming of a "White King" to the throne would presage a period of disasters.

Attendees rocked out to I Was Glad

All coronation ceremonies feature music, and Charles I's was no exception. "Music and Ceremonial at British Coronations" lists six musical pieces performed at his coronation. Each one of these pieces was attached to different parts of the ceremony. None of these were what you might call arena rock, but are instead religious hymns. For example, "Come, Holy Ghost" was performed at the anointing, and "Oh Lord, Grant the King a Long Life" was played during the procession from Westminster Hall to the Abbey.

The "Historical Dictionary of English Music" notes that one tune, "Zadok the Priest," had been performed since the 10th century, when coronations were not performed at Westminster, and has since been immortalized in Handel's 17th-century version. Charles' coronation was not strictly limited to traditional music. His coronation also featured "I am Glad, " played upon his entry into the church. This anthem became a British tradition and has been sung at every coronation since.

His wife refused to attend

Charles I's coronation must have been, it could be said, one of the crowning moments of his life. Nonetheless, the occasion was marked by sadness for the king since his wife (or more formally, queen consort), Henrietta Maria, did not attend.

Britannica details how Henrietta Maria was the daughter of King Henry IV of France and, through a treaty, married Charles at the age of 15 in 1625. She was a devout Roman Catholic and openly practiced her faith in court. This was very controversial in Protestant England, and as queen, it would anger many of her subjects.

Henrietta Maria's Roman Catholic faith was also the cause of her conflict with Charles' coronation ceremony. "The White King" details how she refused to attend, not wishing to be anointed by the Anglican archbishop of Canterbury in a Protestant ceremony. This act would assure her fellow Catholics that she was not about to become a heretic. While this did disquieten Charles, she did have a view of the procession from a nearby house. "The Tragic Daughters of Charles I" tells us that Henrietta Maria was never crowned queen and remained a divisive figure throughout his reign.

He was the last to be coronated with the original regalia

According to Historic Royal Palaces, British monarchs today are invested with St. Edward's Crown — a 5-pound solid gold headpiece — as well as the Sovereign's Scepter with Cross that features a 3,106-carat diamond, and the Sovereign's Orb. All this has been in use since the coronation of Charles I in 1661. But Charles I was crowned earlier, in 1626, so his kingly accessories were somewhat different.

Charles I was invested with the original coronation regalia of King Edward the Confessor (later canonized to St. Edward). This bundle of royal antiques, described by "The Drama of Coronation," consisted of St. Edward's stone chalice, a scepter, several swords, and other symbolic items such as spurs.

Charles would turn out to be the last British monarch to be invested with this regalia, since they were taken and destroyed in 1649 alongside the execution of Charles and the end of the monarchy. As for the crown used by later kings and queens, St. Edward's Crown, the truth is that St. Edward never wore it. According to "Refashioning Medieval and Early Modern Dress," when the monarchy was restored in 1661 by Charles' son, Charles II, a new crown was made and given the ancient name. The only piece of the old regalia that still exists is the Coronation Spoon, which had been sold off before it could be melted.

The coronation nearly fell off script

Any event, no matter how meticulously planned, runs the risk of falling off script. Charles I's coronation was no exception.

"Coronation of a King" describes how after the rather dull and death-filled sermon, the acclamation — an essential part of the ceremony — followed. The acclamation was meant to show that the people confirmed and wanted Charles to be their king. Of course, the people, in this case, were the nobles and elites who had come to the coronation. Regardless, Charles mounted a tall scaffold in the center of the church. The archbishop then presented the king to those in attendance, ending by asking for a general acclamation to confirm their willingness to be his subjects. He was greeted with silence, with no one seeming to know what to do after waiting for a perceived pause in his speech to pass, or not having heard him at all.

As "The Life, Correspondence & Collections of Thomas Howard Earl of Arundel" explains, an eyewitness to the affair saw a noble, Lord Arundel, intervene, telling those present to shout out, "God save King Charles." Then "as ashamed of their first oversight, a little shouting followed."

He was coronated twice

Charles I was actually coronated twice. The first coronation, held at Westminster, was for the king of England. Although England and Scotland were politically unified by that time, they were still separate kingdoms. Therefore, as "Four Scottish Coronations" explains, in 1633, Charles made his way north to be officially crowned king of Scotland.

Traditionally, the Scottish kings had been coronated at the Abbey of Scone. However, it had been destroyed during the Reformation, so it was conducted in Edinburgh instead. The coronation itself was elaborate. The article "Charles I's Edinburgh Pageant" (via Renaissance Studies) explains that this was meant to cement and assert Charles' political power, while simultaneously promoting the idea of a unified kingdom through his connection to the Scottish kings of the past. Much of this political agenda was mixed with religion. "Stuart Succession Literature" tells us that one of his main goals was to pull the Scottish Presbyterian Church to the Anglican Church in order to create a more unified kingdom, with the intent of placing Anglican clergy into their Scottish counterpart faith.

His second coronation sparked a rebellion

Problems arose during Charles I's Scottish coronation, owing largely to him being tone-deaf to political and religious sensitivities. For example, "Stuart Succession Literature" explains that in order to promote Anglicanism, Charles I ordered the coronation ceremony to be held using Anglican rites, which to the simpler Scottish Presbyterian Church smacked of Catholicism. This, plus the fact that the coronation was held in Edinburgh rather than the traditional location of Scone, was viewed as an insult to Scottish politics, identity, and religion. It also didn't help that Charles I, instead of attending the preplanned public celebrations of his Scottish crowning, opted to dine privately — which further alienated the Scots.

As National Museums Scotland describes, matters continued to deteriorate. Charles I saw himself as the head of the Scottish Church, to which the Scots strongly objected, believing that only Jesus Christ could assume this role. In 1639, the Scots broke out in rebellion over these issues in what Britannica calls the Bishops' Wars. These troubles ended with peace with the Scots, where Charles' promised not to interfere with the Church. However, conflict broke out again in 1640, forcing Charles I to summon Parliament for money. This then sparked the boiling tension between the monarch and Parliament, leading to the English Civil Wars, Charles' defeat at the hands of the parliamentary forces, and his subsequent execution.