The Untold Truth Of Westminster Abbey

Even in a country full of really old and really impressive stuff, Westminster Abbey in London, England, is notable for its beauty and longevity. The first religious building on that site was erected in 960, greatly expanded and enlarged over the course of 25 years in the next century, and then mostly rebuilt to the building people know and love today in the 1200s. The abbey has been the location of virtually every English coronation since 1066, as well as the setting for many royal weddings, and is also the final resting place of tons of famous Brits.

Despite what you'd assume based on the name, Westminster Abbey is not actually an abbey, according to History. At least, it isn't anymore. By definition, an abbey is a place where monks or nuns live, and Westminster hasn't been home to a Catholic religious order since Henry VIII split from the church in the 1500s. However, it is still an active church, although these days, you would be forgiven for thinking it catered exclusively to tourists.

Regardless, Westminster Abbey is still super important and super interesting, and there are plenty of facts about it that even most Anglophiles won't know.

The oldest door in the U.K. is easy to miss

When you go to Westminster Abbey as a tourist, you're going to spend most of your time in the main part of the church complex, the one with the high ceiling and all the famous dead people lying around in their fancy tombs. But there are other areas that are part of the abbey that are much less showy, and one very cool historical artifact is easy to miss.

Westminster Abbey is home to the oldest door in the whole United Kingdom, according to its official website. Amazingly, no one knew the abbey was the holder of this record-breaking entryway until 2005. That's when the wood was finally tested and discovered to be right around 1,000 years old. While it's impossible to pin down a completely exact date, the research showed the door was put together in the 1050s, which makes it older than the abbey itself.

Obviously, that means the door used to be somewhere else before becoming a part of one of the most illustrious structures in the country. And wherever that place was, the doorway was much bigger than the one it's in now, since the abbey's website says it's been cut down by as much as 2.5 feet. And while the five boards that make it up are currently weathered and plain, at one point, they would have been covered in painted leather. (The BBC records a Victorian legend that said the leather was actually human skin from an executed man, although, thankfully, this is not true.)

Some famous people have refused to be buried there

Westminster Abbey is a gorgeous building and a significant location for both religious and royal ceremonies, but if you wander around, you'd be forgiven for thinking it's just a very fancy indoor cemetery. There are tombs and memorials everywhere. For centuries, people from all walks of life (okay, mostly the rich and famous ones) have desperately wanted to be buried in the abbey, even if it meant fighting for space.

So it's particularly notable when someone turns down being buried in the illustrious space. Michael Faraday was one of the most brilliant scientists of the 1800s, whose work on electricity was particularly revolutionary, according to the Adam Smith Institute. Had he been buried in Westminster Abbey, he would have fit in perfectly in Scientist's Corner alongside Isaac Newton and, later, Charles Darwin (per Guide London). But he turned down the honor, and Find A Grave records he was buried in London's Highgate Cemetery instead.

Winston Churchill also chose not to be buried in Westminster Abbey. As the 20th century's most famous prime minster, a man seen as a hero for leading Britain through World War II, it would have made sense for him to be laid to rest there. But after he died in 1965, The New York Times reported he had declined the offer, and was instead buried in a small church graveyard in the village of Blandon with other family members, near where he was born.

Some famous people were too scandalous for burial in the abbey

While some people turned down burials at Westminster Abbey, others have had their applications rejected, so to speak. Often this comes down to the fact that the abbey is a religious institution and some people's lives were a bit too spicy for the Church of England to embrace them in death.

The explorer Henry Morton Stanley, of "Dr. Livingstone, I presume?" fame, was well-loved for his exploits in Africa during a particularly colonization-happy period of British history. But an article in the San Francisco Call noted with anger after his death in 1904 that he had been denied burial at the abbey, allegedly because of a lack of space. But the writer believed that had Stanley gone to Africa "with a Bible and a bevy of missionaries, instead of with a rifle and armed followers," they would have found space for him.

Lord Byron is still seen as an archetypal "bad boy," and even more so when he died in 1824 at the young age of 36. At the time, the Dean of Westminster said no way could Byron be interred there, because of his "open profligacy," according to the abbey's official website. Nor had feelings changed 100 years later, as a 1924 article in Maclean's reported the then-dean refused even a memorial plaque for the poet to mark the centenary of his death. Byron would eventually get a memorial flagstone in 1969.

And Oliver Cromwell was originally interred in Westminster Abbey for a short period – until the monarchy was restored and he was thrown out real quick.

Ben Johnson was buried standing up

So let's say you wanted to be buried at Westminster Abbey, and you'd managed not to have such a scandalous life that the abbey refused to accept you. What then? Well, it seems you had to pay for the cost of your burial, and for the land you were going to take up, at least if the playwright – and Shakespeare's contemporary – Ben Johnson's experience is anything to go by.

According to Westminster Abbey's official website, despite being a successful writer and a friend of royals, Johnson was usually broke. It's not clear how he got his plot in Westminster Abbey, although it might have been a gift from the king, or he might have paid for it himself. However, "plot" is perhaps too grandiose a term. For whatever reason, possibly financial, Ben Johnson's corner of Westminster Abbey is a square about a foot and a half across. It is so small that he had to be buried standing up.

Now, Westminster Abbey has a space problem, but this wasn't related to that issue, nor was it normal for people to be buried this way as a space-saving measure. Johnson is the only person laid to rest this way in the abbey. This became a problem in 1849 when a grave being dug next to his resulted in Johnson's skull rolling down to his feet, but the disturbance at least confirms the burial was not a myth.

Why King Charles III didn't get married at Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey has been a popular location for royal weddings. Most famously in the 21st century, Prince William and Kate Middleton were married there in 2011. The abbey's official website says that it's been the site of 16 royal weddings — including the future-Queen Elizabeth II to Prince Philip — with the first one happening way back in the year 1100.

One notable modern couple who did not get married at Westminster Abbey, though, was Prince Charles and Lady Diana Spencer. The abbey was the expected location, especially since Charles' sister, mother, aunt, and grandfather had all had their weddings there in the past 60 years. However, the couple selected St. Paul's Cathedral, in a different part of London, instead.

There were probably two reasons for this decision. According to Time, Charles and Diana already knew how popular they were (okay, how popular she was), and they wanted room for the crowds outside and lots of guests inside. Marrying in Westminster Abbey would have limited the guestlist to a mere 2,000 close friends and family, while St. Paul's seats 3,500. But there may have also been a more personal reason, at least for Charles. His great-uncle Lord Mountbatten had been assassinated less than two years earlier, and his funeral – in which Charles took a central role – had been held in the abbey (though Mountbatten was buried elsewhere, per Biography). The memories may have still been too raw and painful for Charles to return for his wedding.

Samuel Pepys kissed a dead queen at Westminster Abbey

The 17th-century diarist Samuel Pepys recorded lots of interesting things in his famous diaries, as well as the details of many of his birthdays, according to the Royal Museums Greenwich. In general, they were like any other day, although he might do something fun like go to the theatre or have some friends over.

Then there was Pepys' 36th birthday in 1669. At first, it might seem kind of boring, since he just took some relatives on a tour of Westminster Abbey. This mainly meant looking at tombs, but back then, there was one tomb in the abbey that was definitely worth seeing. Catherine of Valois lived in the early 1400s and married the English king Henry V, per The Chapel of the College of St. George. She died aged just 35, and her body was embalmed, then she was interred in Westminster Abbey. Her remains, however, were disturbed around the year 1500, and her corpse remained visible to gawkers for over 200 years.

When Pepys saw the long-dead Catherine that day, it was ... well, it was certainly something at first site. He grabbed the corpse and, as he wrote in his diary, "I had the upper part of her body in my hands, and I did kiss her mouth, reflecting upon it that I did kiss a Queen, and that this was my birthday, thirty-six years old, that I did first kiss a Queen."

Queen Catherine was finally reinterred properly in the 1800s.

The theft of the Stone of Scone

While England and Scotland might technically be on the same side now, for a long time, they were separate countries with a fraught and bloody history. The kind of history that a few hundred years of unity isn't enough to erase from people's minds. One insult the Scots didn't soon forget, according to Britannica, was when Edward I invaded Scotland in 1296 and took off with the Stone of Scone.

Also known as the Stone of Destiny, Scottish kings were traditionally crowned while sitting on the stone, so taking it was a stab directly at the heart of the country's government and traditions. To add insult to injury, Edward had a chair built around the stone, and English kings were crowned in that chair in Westminster Abbey from then on. The Scots could do nothing about it.

Until Christmas 1950. That's when a small group of Scottish nationalists broke into the abbey, ripped the big rock out of the Coronation Chair, and took it back up to Scotland. The young adults were, by one of their assessments, not very good at committing crimes. They didn't even try to cover their tracks and were swiftly apprehended. But they never saw the inside of the courtroom. Ian Hamilton explained to the Paisley Tartan Army in 2008, "We got away with it ... they were terrified the Scots would have risen up if we had been sent to jail."

England returned the Stone of Scone to Scotland – voluntarily this time – in 1996.

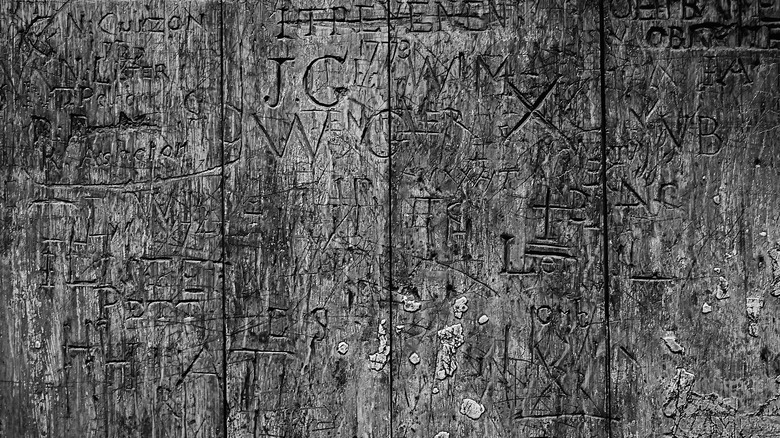

Vandals have been leaving graffiti in Westminster Abbey for centuries

People in the past weren't so different from us. They wanted to leave their mark on the world, even if that meant defacing one of the most famous buildings in England or damaging the priceless artifacts it held. If you walk around Westminster Abbey and look past all the grand tombs and religious decorations, you'll notice there is graffiti pretty much everywhere. In most cases, really old graffiti.

Many tombs in the abbey, especially the nice, supple wooden ones, are covered with the initials of visitors from centuries past. Some of the vandals even helpfully left the date, so no guesswork needs to go into figuring out when it's from. The Coronation Chair may have been damaged when the Stone of Scone was stollen, but it had been treated badly long before that. According to the Westminster Abbey website, there's graffiti carved into the back of the chair dating back to the 1700s. One man even wrote, "P. Abbott slept in this chair 5-6 July 1800."

At some point, graffiti becomes so old that even those in charge of the abbey can't be made about it anymore. It's become part of the building itself. The official Westminster Abbey Twitter account even tweeted a photo of some of the old graffiti etched into the stone walls in 2018, explaining it "was scratched into a wall in the Abbey many hundreds of years ago," while making clear that "no one scratches their mark into our walls these days!" So you've been warned.

A moving and visceral tomb for a beloved wife

According to Susan Jenkins, curator of Westminster Abbey, the church is home to around 600 large pieces of sculpture. In all that amazing art, it takes a lot to stand out. And no monument in the abbey is more visually arresting than the "The Nightingale Monument."

Since it's in a side room off the main area of the abbey, lots of people probably miss it, but once you are in front of it, you can't mistake it for anything else. The massive stone carving, a two-level statue, is of Death, complete with a spear, coming from under the earth to claim the woman above, while the man impotently holds his arm out to try to stop the inevitable. This depiction is an emotional interpretation of a real-life event, when Elizabeth Nightingale died after going into premature labor in 1731. Her husband Joseph was powerless to keep her on this side of the veil, and could do nothing but commission a grand monument to be erected near where they were both eventually interred in the abbey.

The Westminster Abbey website records that John Wesley, a founder of the Methodist denomination of Protestantism, was blown away by the monument, saying "the marble seems to speak." And the author of "The Legend of Sleepy Hollow," Washington Irving, opined that the tomb was "among the most renowned achievements of modern art." While the "modern" in that statement is now relative, visitors today can't help but agree with him.

Visitors had sticky fingers around Henry III's tomb

Henry III was king of England for 56 years, according to Westminster Abbey's official website. This was extra impressive considering he lived in the 13th century. His numbers were helped along by the fact he became king as a child, but he still managed to live to the ripe old age of 65.

After Henry died, his body was stored in a temporary space while his tomb was built. This took a whopping 19 years, but it was worth it for the final result. The abbey describes just how fancy this final resting place was: "Henry's large tomb is of Purbeck marble with slabs of purple and green antique porphyry set in the sides and inlaid with gilded 'Cosmati' mosaic and colored marble and glass." Cosmati mosaics may have been a particular favorite of Henry's, since, as part of his rebuilding of the abbey, he brought highly skilled craftsmen from Rome to do this same technique on many areas of the floor. Overall, the work put into Henry's tomb was beautiful, extremely detailed, and very expensive.

Sadly, you will just have to take history's word for it, since over the centuries, many visitors to Westminster Abbey decided a piece of Henry's tomb would be the perfect souvenir. Only one of the four sides still has any of this fancy decoration on it at all. These days, you almost certainly wouldn't be able to get away with nicking some, so don't even try.

Some misericord carvings were inappropriate

While there haven't been monks living in Westminster Abbey for centuries, the church was originally built with them in mind. One of the inevitable parts of a monk's daily life was long and tiring religious services. Rather than having old or out-of-shape monks collapsing in the aisles, some areas of the church have what are known as "misericords." Westminster Abbey's official website says these are essentially wooden ledges on the underside of folding seats. This way, when a monk stood up, the seat could flip up (like a movie theatre seat), and this small ledge would be just enough room for the monk to prop himself up, while still standing.

Because every detail of Westminster Abbey just had to be gorgeous, the misericords are elaborately carved with scenes of people and nature. While the ledge itself is flat (fortunately for the monks), the rest is decorated, and – since these carvings were virtually always hidden, either by a standing monk or the seat being flipped down – the craftsmen who made them were pretty much allowed to depict whatever they wanted. Some of them took that freedom and ran with it.

While many of the misericord carvings in Westminster Abbey are relatively straightforward, the site lists a few that raise an eyebrow in a religious setting, including a naked man and woman playing instruments, a woman smacking a man for groping her, a devil carrying off a monk, a naked family of eight, and a naked man being attacked by a bear.