Scientists Who Were Ridiculed, But Were Right

Looking back on certain discoveries that have become commonplace, it's wild to think that a lot of them were laughed at. The lightbulb, for instance, was widely rejected, as per New Scientist, before it became such a piece of everyday life that you probably haven't even thought about a lightbulb all day. It's just a part of everything, and it was laughed at. And it's not alone.

A lot of the scientific thought that would and eventually did advance our understanding of the universe was seen as heresy. The world used to be flat, and the earth used to be the center of the universe — and oftentimes people who thought otherwise were burned at the stake, beaten, or forced to recant on penalty of, well, being burned at the stake or beaten.

Perhaps it's just humanity's nature to be so skeptical, to be so engrained in our way of life that when something new comes along, the immediate impulse is to reject it. How else do you explain a public that saw the lightbulb as a foolish instrument that wouldn't undo the reliability of gas-lighting?

As such, there are a whole slew of scientists and inventors who were absolutely right in what they did but were ridiculed for doing it, only to see their beliefs and contraptions become everyday knowledge people barely even think about anymore. Here's a small chunk of those revolutionary thinkers.

Mary Anning

Mary Anning was just a downright amazing person. She was raised hunting dinosaur fossils with her dad and brother, but when her father passed away and her brother stepped up to support the family, it was left to her to discover the fossils she had previously hunted as a unit. When she was just 12-years-old, she and her brother uncovered an ichthyosaur head on the beach in England, and young Anning proceeded to dig up the rest of it, according to the Natural History Museum.

At the time, scientists called it a crocodile and any manner of things other than what it was. Of course, it was eventually labeled as a prehistoric creature but only when the leaders of the scientific world (all men, mind you) decided it was so. Too often, those same men would buy Anning's skeletons, identify them, release the news, and never give her credit.

That wasn't even the bad part. Later, Anning would discover the first complete Plesiosaurus skeleton. It was an amazing find for a scientific world that simply did not respect her. Naturally, they called the fossil a fake and denied Anning any credit. Even the father of fossil finding, George Cuvier, disputed it, and the Geological Society of London (which wouldn't admit women until after Anning's death) held a special meeting in which even Cuvier had to admit his mistake.

Anning discovered an insane amount of fossils, but the men who led the scientific world continued to scorn her advances.

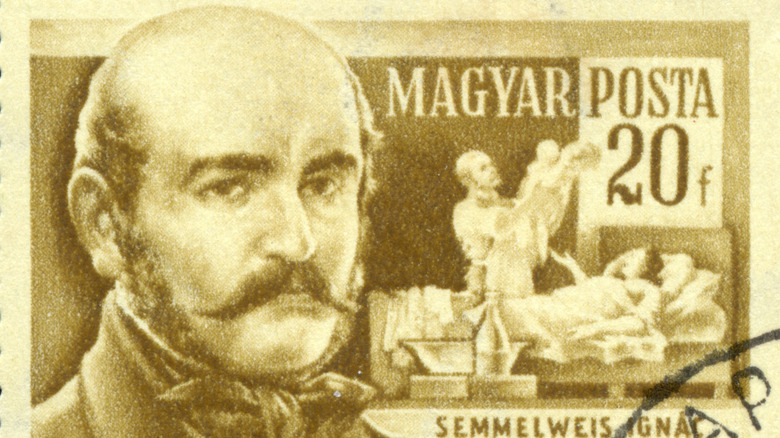

Ignaz Semmelweis

Probably one of the most tragic stories of all time, never mind tragic stories related to an idea that is common sense now. An idea that was so scorned and laughed at when introduced that the results were literally deadly.

In 1846, a Hungarian physician named Ignaz Semmelweis had a pretty crazy idea. According to NPR, he wanted to get to the bottom of mortality rates in mothers just after childbirth, so he began a study of two maternity wards — one staffed by female midwives and one staffed by all male doctors. What he discovered was

a mortality rate five times higher at the male-run clinic than the midwife one. His theories ran from birth position to a priest ringing a bell, but he couldn't solve the equation. Not until he found the solution — the male doctors who had been delivering babies also conducted autopsies. The midwives didn't.

Semmelweis figured that had to be the answer. Doctors carried "cadaver particles" to the birthing table, and it infected the babies and mothers. After instructing staff to clean their hands before delivering babies, the results were quite clear — it made all the difference. Go figure, right?

Doctors didn't like this, according to NPR, because the implication was that it was their fault. Spoiler: It was. No one would take his discovery seriously, and after years of anger and frustration, Semmelweis wound up dying from being beaten in an asylum. He was infected by sepsis — exactly what he was trying to prevent mothers from getting — and died from the infection.

William Harvey

The human body really is a marvel. It has so many arteries and veins that if you stretched them out, it would amount to 60,000 miles, notes the Cleveland Clinic — enough to wrap around the world two whole times. There are 79 organs, 206 bones, and a brain that is still a conundrum. Step back a few centuries and our understanding of the body was even skimpier. Enter William Harvey, a man who had figured out how blood circulates through the human body, according to Medical Daily.

He published his findings in 1628, but the scientific world was still so engrained in their previous beliefs, which dated back to the second century when a physician named Galen posited that the liver produced blood from food, where it then circulated it to the heart and lungs. Today, that just sounds wacky. Even though Harvey had the actual truth about the heart and circulation, his peers still clung to beliefs dating back 1,500 years.

Not only did they cling to those beliefs, though, they rubbed Harvey's nose in his own principles. It became so bad that, according to Rob Dunn's book, "The Man Who Touched His Own Heart: True Tales of Science, Surgery, and Mystery," Harvey became a recluse. He shut out the world entirely to escape the ridicule and was even quoted saying, "Much better is it oftentimes to grow wise at home and in private than by publishing what you have amassed with infinite labor, to stir up tempests that may rob you of peace and quiet for the rest of your days."

William B. Coley

William B. Coley was a bone surgeon and cancer researcher at New York Cancer Hospital, according to Newsweek, and what he proposed was something a bit, well, out there. While so many scientific discoveries are pretty easy to understand and difficult to see where the critics came into the puzzle, Coley's idea spurred on a good deal of critics, but it's pretty understandable why.

According to the Iowa Orthopedic Journal, in 1891, Coley tested one of his theories by injecting streptococcal bacteria into a cancer patient. His belief was that while yes, this was an infection he was introducing to a susceptible victim, the infection would shrink the cancer tumor. Lo and behold, he was right. His theories had proven true, and just like that, the birth of immunotherapy was witnessed.

These injections of otherwise nefarious infections became known as Coley's Toxins, and he would go on to utilize this treatment on over 1,000 patients at the New York Cancer Hospital, spurring the natural immune systems in people suffering from cancer. The results proved that immunotherapy was a valid form of treatment, but meanwhile, Coley's peers viewed his results as false. They ridiculed his approach, and with chemotherapy and radiation treatment on the rise, immunotherapy took a back seat. But, over time, it has seen a resurgence, and nowadays Coley is seen as the father of it all.

Michael Servetus

While proposing new and exciting ideas in the modern world has always been risky busines — at best leaving you at risk of being ridiculed and mocked, at worst driving you to madness from lack of approval (though even that's not happening very often) — doing the same in the Middle Ages was another ask entirely. Take Michael Servetus for example. Servetus was both a physician and a theologian, though he had some ideas what didn't exactly jive with the teachers of the church.

Namely, his thoughts on circulation within the pulmonary system. Servetus published his beliefs in a book, but he included in said book a bunch of criticisms of the church and Christianity, according to Wired. Probably not the best place to hide necessary information about pulmonary circulation, but hey, it was a different time.

Regardless, the entire book was deemed heretical. Which part? Well, that's a great question. For the Catholic Church, all of it was heretical, making Servetus' beliefs surrounding the pulmonary system also unorthodox — perhaps by happenstance, perhaps because the Catholic Church really didn't like what he had to say about human lungs. Regardless, he ticked off the church so much that even both the Catholics and Protestants agreed he was a heretic, according to Britannica. Sadly for Servetus, this landed him on a burning stake, accompanied by a bunch of his books.

Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin

Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin was an astronomer and one of the best to have ever lived. We know that now, of course, but at the time, she had a problem that many scientists like her had — she was really good at something only men were allowed to be good at.

As the BBC's Science Focus details, she was a pioneer in many ways. In academia, she received a doctorate from Radcliffe College and was a professor at Harvard — two accomplishments that were unheard of for women at the time. She also discovered the composition of stars — and the fact that she was a woman was cause for ridicule. Ever since she was a child, she had been observing the stars, so her walk in life seemed pretty set from a young age. While she was expelled from school for her curious mind, that was never going to stop her exploration of the cosmos.

When just a graduate student, she put her major discoveries to paper in her thesis, in which she analyzed the patterns of stars and galaxies, as well as stated outright her findings that stars were primarily composed of hydrogen, according to Nature. While her thesis met with rave review, the little bit about what stars were made of was not. In fact, she was so widely criticized for daring to question an established belief (that stars were composed like Earth), that she admitted that she must have made a mistake.

Later, when it was seen how right she was, it was one of her chief critics that took initial credit, before eventually conceding that it was Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin's discovery all along.

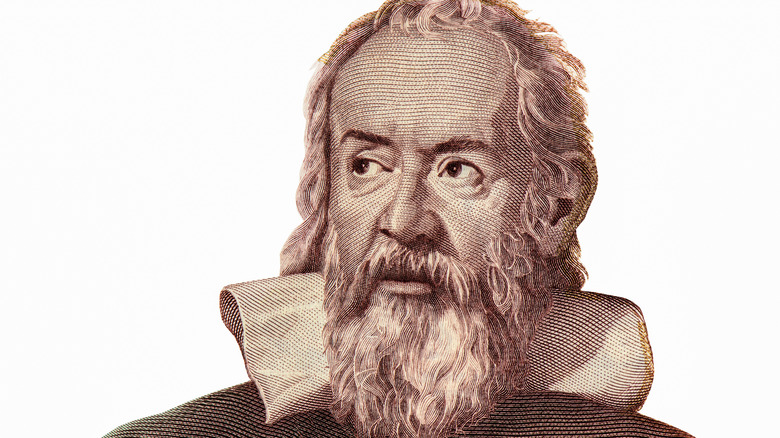

Galileo

Galileo is more or less a household name these days, but during his time, he found himself facing down a burning stake if he dared to continue to state what has now become such an obvious fact — that the Earth revolves around the sun. When he wrote his book, "Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems," he outlined his logic for stating the heretical views that the Earth is actually not the center of the universe at all, according to Smithsonian Magazine.

As with most things that beg to differ with traditional Catholic values, this did not sit well with the pope, who never quite was a fan of having his views questioned. The Inquisition was underway, and that meant that anyone who dared disagree was burned at the stake. After all, why have a logical discussion when you can just burn the other side. Ironically enough, Galileo was quite adored by the pope and received some funding from the church in order to continue his endeavors. Little did the pope know what he would find — that the Earth was moving. Surely the center of the universe should not be moving.

Galileo was arrested for heresy and forced to recant his findings, which he did, though it didn't change his actual beliefs.

Alfred Wegener

It's wild the lengths scientists will go to not just to disprove a theory they don't agree with but to outright shame and dehumanize whoever dared posit that conflicting theory in the first place. No one learned that better than poor Alfred Wegener. Wegener had the very sensible belief that the continents on Earth were adrift — they were moving. The planet was 70% water, after all, as per the United States Geological Survey. Wegener delivered this controversial viewpoint at the Frankfurt Geological Society in 1912, according to Smithsonian Magazine, and no one seemed to give a hoot. When he published an article about it, same thing. Crickets, even.

However, while recovering from his service to Germany in World War I, he turned it into a book, which hit the English language market in 1922 — and that's when Wegener's entire world changed. The kickback was vicious, and it could largely be ascribed to the anti-German sentiments around the globe. The Germans were, after all, the "villains" of World War I, and to the British, that added further illegitimacy to his book. When the Americans got involved, the insults came in even heavier. But to add to the vitriol, Wegener's German peers dug into his credibility as well, demeaning him with personal insults, name-calling, and the like.

It didn't look good for poor Wegener's theory, except, of course, for the fact that it was correct. Fast forward a few decades, and a new wave of geologists verified what Wegener had been saying all along.

Abu Bakr al-Razi

There are certainly good and bad places and times to introduce a scientific theory. The Inquisition was a particular bad time, for instance. But another bad time is the pre-modern Islamic world. That's where Abu Bakr al-Razi began to pioneer his way into modern medicine, leaving behind a legacy that would hail him as an essential forefather of the entire field, according to the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. But that's just his legacy. His actual life was riddled with contempt that would lead to physical suffering and torture, all for believing in something more.

Abu Bakr was a doctor first and foremost, and he operated a hospital in modern-day Tehran, as well as in Baghdad. His discoveries and accomplishments are massive, including understanding the eye's reaction to light, as well as being a forerunner in the understanding of smallpox and measles. He also challenged a lot of the classic belief, largely ancient physician Galen's writings, including that a fever is merely a symptom and not a disease in and of itself.

For all of his arguments, he was criticized for being ignorant and arrogant and was occasionally even beaten, according to Encyclopedia.com, for not providing proof of his claims. His claims that all proved to be true, by the way.

Giordano Bruno

The midst of the Catholic Inquisition is just not a good time to start proposing wild new ideas about the universe. The Earth is the center, and everything revolves around it because the Catholic Church says so. Unfortunately for many, many scientists, including Galileo himself, to introduce any other theory was to put your life at risk. Giordano Bruno surely knew the risks when he dared to posit the bold theory that there were other universes out there besides our own.

Like so many others, Bruno is credited with being many things — philosopher, astronomer, mathematician, and occultist, according to Britannica. His major claim to fame, however, was his belief that the universe was infinite. Up to that point, all he'd really done is become a friar, dig into scientific theories, quit his life as a friar, and repeatedly flee one European country after another in search of safety with which to explore his scientific mind. After ditching Catholicism, he soon had to ditch the other faiths as well, because no one wanted to believe anything other than the established principles of the universe.

He then made the completely ludicrous claim that the Bible was a fine religious text but not a reliable astronomical one. Bad move, Bruno. After wandering a bit longer, being excommunicated from more faiths, he was finally duped by the Catholic church and burned at the stake for his heresy, which is obviously now a scientific fact.

Alice Catherine Evans

Here comes another one that is worthy of an eye-roll, simply because the very thought that this belief was doubted is ridiculous. Alice Catherine Evans was a microbiologist. She had been raised on modest means, but her scientific mind was always destined to do more than teach. She pursued bacteriology in college, encouraged by a supportive faculty that saw significant promise in her pioneering mind, according to Encyclopedia.com.

She was soon hired on by a team looking to improve the flavor of cheddar cheese, and that's when her scientific exploration began to formulate around a somehow audacious opinion. After moving to work with the USDA's Bureau of Animal Industry, she was shunned for being the only woman employee, but that didn't stop her from exploring what would eventually make her a fixture in the bacteriology landscape.

Turns out, milk from cows and goats needs to be pasteurized before it can be consumed by humans, otherwise significant bacteria presence can cause illness. Again, makes total sense. But in 1917 when she published her findings, the response was less than supportive. It was a combination of her being a woman and a general consensus that surely this new finding could in no way be true.

Well, spoiler, it was true, and it's all thanks to Evans.