The Long And Storied History Of Garden Gnomes

There's really nothing else out there like the garden gnome. Something infinitely recognizable for a specific look, that can trace its lineage back centuries. And not that much has changed over those centuries. They still serve one specific purpose and look one general way. Good luck thinking of anything else so incredibly unique, yet with such longevity and a style that has stayed remarkably the same, dedicated to a singular purpose, over the course of its lengthy history.

As such, pretty much anyone could identify a garden gnome on sight. A tall, pointy hat. A bushy white beard; very short, no more than a foot or two tall. A round, bulbous nose. They've become so popular that you can own gnomes dressed in your favorite sports team gear, as well as repping any brand you like enough to sport in your yard. There's even a gnome mascot for the Expedia travel company, and more interesting trends popping up in the gnome-sphere.

All this to say, garden gnomes have a long, bizarre history that spans ancient statues of deities, real-life human beings, and the modern iteration of the gnome that also looks a lot like what Snow White's seven dwarves look like. It might be surprising to learn how far back garden gnomes go in the annals of time, but let's dig into that storied history, one step in the evolutionary process at a time.

Ancient Roman forerunners

Like so many other storied things around the world, the origin of garden gnomes can trace its utility all the way back to the Ancient Romans. While the Romans didn't necessarily have gnomes, because the word itself didn't even exist yet, the concept of a small garden guardian, usually a statue, and usually of some notable power, was alive and well. That's because the Romans would place small statues of gods from their expansive pantheon in their gardens to ward off evil spirits and to ensure a successful harvest, according to Trees.com.

More often than not, that god would be Priapus, who, according to Theoi, was the god of vegetable gardens, as well as vineyards, beehives, and flocks. He was often depicted as a dwarfish man, which could have just been a coincidence, given that gnomes have dwarfish qualities, or it could well have been the direct godfather of the internationally renowned garden gnomes.

Romans relied heavily on mortal interactions with their gods and frequently turned to them whenever possible. Given how many gods they had and how specific their responsibilities were, it makes sense that they would turn to the gods to protect something as important as agriculture and livestock. Thus the very idea that would sprout into bearded little gnomes was sewn in the soil of ancient days.

Paracelsus and the origin of gnomes

In order for garden gnomes to start populating the various vegetative stomping grounds of the world, there first had to have been the introductions of gnomes themselves, and for that, we need to look to the 17th-century Swiss jack-of-all-trades, Paracelsus. An alchemist by trade, Paracelsus connected the pieces between chemistry and medicine, and the modern world benefitted immensely from it, according to the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

Believe it or not, gnomes had a connection to all that as well. According to Folklore Tuesday, Paracelsus saw gnomes as one of the four beings who represented the "Empedoclean elements of Earth." Undines were associated with water, salamanders with fire, sylphs with air, and gnomes with the earth. This, then, is another line of connective tissue with how gnomes ended up being guardians of gardens. The caveat was they had to stay among their own element. Gnomes could pass easily through rock, earth, and vegetation, but if exposed to water, fire, or air, they began to die.

Paracelsus drew his inspiration for their appearance from the Ancient Greek pygmies, which were described at length in "The Iliad" as small, mountain-dwelling creatures. They were also included in Pliny's "Natural History," with all of their major characteristics staying true across records. The only minor difference is that while Aristotle once said that pygmies live underground, Pliny and Homer begged to differ.

Other gnomish precursors

While Paracelsus gave a pretty good indication of what a gnome was and what they could do, the idea of a garden gnome was still a few centuries off. In the meantime, a number of other precursors similar to the Roman Priapus statues began to spring up, inching closer and closer to the garden gnomes we know today. First came the Italian "gobbi," which literally means "hunchback" or "dwarf," according to Business Insider. The emergence of gobbi statues in Italian gardens came around the early 1600s, just a few decades after the death of Paracelsus.

Not long after the gobbi came the "House Dwarves" of the 1700s. These are about as close to gnomes as you can get without being actual gnomes. They were small porcelain dwarves that literally became gnomes when they went out to protect the garden. When they came back into the house, they turned back into dwarves, but every time they went outside to do their dwarfish duty, they became gnomes. Which begs the question why not just call them gnomes in the first place, but regardless, these little House Dwarves were popular from their origin in the 1700s all the way up to the manufacturing of the first ever garden gnome in the 19th century.

The hermit in the garden

While seeing dwarfish or impish statues, even statues of Priapus, as precursors to the soon-to-be expansive growth of garden gnome culture, there is another precursor that is rather bizarre and difficult to wrap the noggin around. According to Atlas Obscura, they were called the "hermit in the garden," and while that may sound like a cute little moniker for little gnomish statues, it is nothing of the sort. It is an actual hermit — as in a living human being — who was hired to live in a hovel in a rich person's garden, not say anything, never bathe, and just be a hermit for seven whole years, being paid for their services every step of the way. Oh, and they had to dress up like druids.

Gordon Campbell, a professor from the University of Leicester, wrote a whole book on this completely batty concept, called "The Hermit in the Garden: From Imperial Rome to Ornamental Gnome," in which he explores this bizarre fad that struck Georgian England right about at the turn of the 19th century, and if ever there was a sign that a better garden guardian is needed, this had to be it.

This traces all the way back to Roman times as well, during Emperor Hadrian's reign. He had a villa unearthed with a small cottage for a single-person retreat, and it's believed that this is the introduction of the concept of hermits, which then goes all the way through the papacy and into Georgian England.

Sir Charles Isham and the British gnome wave

Individual garden gnomes began to circulate in Germany in the early 1800s, but it was a British wave that grew their popularity significantly, according to Garden Collage. When Sir Charles Isham visited Nuremberg, Germany, he brought back with him 21 terra cotta gnomes for his personal garden. This coincided with the fad for garden hermits but added a more humane tilt to having garden protectors.

However, the gnomes did not become an immediate sensation in England, or even just in the Isham household. Isham's own daughters did not believe the bearded helpers were up to par with the rest of the estate's decor, and removed 20 of the gnomes, leaving just one, named Lampy, to do the work that he had once shared with his numerous brother gnomes. When Lampy was later rediscovered, according to Garden Collage, he became known as the oldest gnome in the world.

Of course, when people started to wise up to the illogical practice of live-in garden hermits, Isham was there to draw attention to his cheaper, smaller, and altogether better idea — the gnomes that he had pulled from Germany. This, in turn, gave rise to the wave of gnome mania, and it would take a good deal to curtail it.

Philip Greibel's mass production of garden gnome

After all the dwarves, minor deities, and actual human beings populating the world's gardens, the first actual garden gnome emerged in Germany in the early 1800s. However, they wouldn't be mass-produced until the late 19th century, according to the original factory itself, which is still in operation today. The creator — Philip Greibel — apprenticed as a porcelain maker and then made his way into the craft of "animal head modeler," and then went on to found the very ceramics factory that is the birthplace of garden gnomes the world over.

While Greibel produced the Gräfenroda garden gnome, he began his ceramics trade in the manufacturing of animals and other small creatures, alongside other craftsmen who shared the factory space. All told, they created such an impressive collection of ceramics that they made an appearance at the Leipzig Trade Fair, bolstering the reputation of the factory.

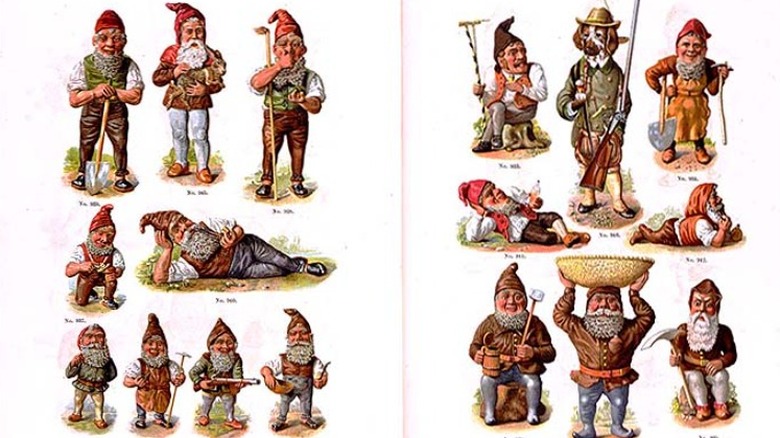

The garden gnome itself, though, was not part of the repertoire on display until some 20 years later, when the Gräfenroda garden gnome hit the world stage and triggered an industry that no one saw coming, and that no one could stop. According to the Gnome Home, Greibel's factory produced upwards of 300 different garden gnome characters in a wide variety of sizes, lending serious credibility to just how popular these creations were at the time.

The war years

You'd think that, with the British and Germans mass producing these cute little garden guys, nothing could get in the way. Generally, you'd be right, but unfortunately, on the timeline of the garden gnome, two big things happened between 1900, when they began to grow in popularity, and the modern day. Those two big things were World War I and World War II. With Germany in flux, at war, and crumbling to bits, garden gnomes became something of a luxury that their economy could not afford, according to Die Zwergstatt.

Most factories there were repurposed to build arms and armaments for the war, and the demand for such luxury items had taken a serious dive as Germany's political and economic situation spiraled up and down, but mostly down. According to Trees.com, the decline of gnomes was as prevalent as the decline in most luxury items, never mind the fact that the production just wasn't there anymore.

It would take a shot in the arm to get gnomes back on the track they were set on before World War I, and they got that shot in the arm with the release of "Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs" in 1937, according to Trees.com. Just like that, the dwarves reintroduced the gnome look to the collective consciousness, and just like that, demand went right back up again.

The evolution of the gnome look

Nowadays, you say the word "gnome" and practically anyone could tell you what they look like, but that wasn't always the case. Early descriptions of gnomes going back to Paracelsus were just that — descriptions. Actually coming up with their look was a matter of creative interpretation. They were always seen as small, comparable to pygmies and dwarves, which lends itself to a certain look, but early iterations of the gnome garden statues in the Renaissance could reach as high as 6 feet tall, according to WBOY. When Germany started to produce them, they were little more than 3 to 6 inches tall, and they weren't based on any particular stories of gnomes at all. Essentially, they were becoming their own thing.

Yet, no matter the height and attire, what gnomes look like has always stayed pretty similar, with the pointy hats and bushy beards. With the introduction of "Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs," the attire began to vary, but even going back to the original factories, there were over 300 gnome characters being produced, all of which had their own quirks or identities.

And there were female gnomes, too, according to Love To Know. Female garden gnomes had long hair, wore simple dresses, and boasted similar faces to witches.

The Gnomes book of 1976

While Snow White's adorable little seven dwarfs may have given new aesthetic qualities to the resurgence of the garden gnome, another immense step towards their near-global domination was a curious little book in 1976 called quite simply, "Gnomes." Written by Wil Nguyen and Rien Poortvliet, these two Dutch authors aimed to add a little more background to the wide world of gnomes. Since folklore was limited to earthen gnomes of Paracelsus fame, as well as whatever was carried over from pygmies and dwarves, there was a good deal of backstory lacking in the implementation of these bearded creatures.

That's what "Gnomes" solved. Complete with illustrations, this book is literally an encyclopedia of the backstory of gnomes, not just as a general term, but on an individual level, giving life and history to various types of gnomes. While all of it is completely made up (right?), it filled a gap that the gnome industry needed, providing a little more context — albeit fictional — as to why these little creatures were popping up in everyone's gardens.

The Muskogee Phoenix summarizes the book perfectly, hitting on a number of the individual stories given to various gnomes in the book. This book was so popular that it was a New York Times bestseller in 1976, and remained atop the list for an entire year. Needless to say, plenty of people were buying gnomes after that. We do live in a capitalistic society, after all.

Diversifying the use of gnomes

Gnomes have had very specific purposes since their beginning. They oversaw the garden. They protected it from evil, be it spirits or other nefarious beings. They ensured that all flora and fauna were kept safe and nurtured to good health. They made sure that their owners could count on a bountiful harvest and not have to worry about pests or plagues. But the question was inevitably going to come up eventually — what if gnomes want to do other things besides tending the garden?

The modern-day has answers for that. Look no further than the Expedia commercials with a gnome as the mascot. It stands to reason that this very gnome started in a garden somewhere and aspired to do something else with his life. The digital footprint that gnomes are now leaving is pretty extensive too. One example is the activity of gnome-spotting. Martha's Vineyard Times highlights this activity in their guide of the grounds, encouraging visitors to spot the gnomes hiding throughout the area.

Similarly, a travel blogger from Camelid Country documented a successful gnome-spotting adventure in Wroclaw, Poland, a city littered with garden gnomes who were tired of the garden and aspired to a life in the big city. Gnomes are diversifying their professional qualities, and it's a great thing to see.

Gnome Liberation Front

Gnomes are certainly learning to diversify their resumes, but the majority of them are still working in gardens, where they've been placed by owners who may or may not have asked what they actually want to do with themselves. This has led to a very legitimate organization called the Gnome Liberation Front, which has taken up the mantel of ensuring that gnomes are given the freedom of choice that they deserve.

Seriously, that's what they're doing. According to ABC 7 News, a string of, let's call them gnome-nappings, caused a panic in Colorado, as gobs of garden gnomes were "liberated" by the GLF. They then sent a picture of the gnome to the owner, including the name it was never given, and vowed to never return the gnome to the garden. This is not exclusive to Colorado either. In Great Britain, a similar problem has arisen, according to The Mirror, with gnomes disappearing left and right, being given names, and legitimately "liberated" from their life of toiling away in the garden.

So if you have a garden gnome, you may want to find out their name, and maybe see if they have any other drive in life, otherwise, the very legitimate Gnome Liberation Front may come for your dearly beloved bearded helper.