The Murder Of Helen Jewett: America's First Tabloid Murder Trial

The 1836 murder of Helen Jewett was, at least at the beginning of the long and lurid tale, a tragic but not entirely unforeseen event. As ThoughtCo reports, Jewett was a sex worker in antebellum New York City. One day, she was found dead in her sleeping quarters with three holes in her head and her bed set on fire. Her client for the night, whose identity would form the basis of much of the trial and controversy to follow, would become the prime suspect.

But while a murder like this "would likely have been quickly forgotten," per ThoughtCo, there were elements of Jewett's case that caught the attention of the American public. NWSA Journal notes that Jewett was said to be not just beautiful, but cultured and intelligent. The accused killer, Richard Robinson, was also a fairly well-off young man who exchanged literary references and romantic turns of phrase with Jewett.

Most powerful of all, however, were the newspapers that kept the public's attention on the case and whipped readers into a frenzy before the term yellow journalism was coined. The New York Herald took the lead in this arena, publishing stories that discussed the details of the bloody crime scene, the people involved, and the trial that determined Robinson's fate. This is the story of America's first major tabloid murder trial.

The murder of Helen Jewett shocked 1836 America

Though the events before and after the murder of Helen Jewett were caught up in spirals of rumor and outright lies, the facts of her death are surprisingly straightforward. According to "The Murder of Helen Jewett" (via The New York Times), it first became clear that something had gone wrong in the early hours of April 10, 1836. In Manhattan, brothel owner Rosina Townsend was awakened by knocking on her bedroom door. Thinking it was a customer, she stayed in bed and told the person to get his lady companion to let him out of the locked house herself, which he seemingly did. When she got up later to let another customer into the building, she saw that a lamp was out of place and the back door was left open.

Townsend began moving through the home to check the rooms for unwanted visitors. When she made it to Jewett's habitation, the door opened to reveal a room full of smoke. Calls of "fire" brought watchmen running to the brothel. Meanwhile, Townsend and another woman tried to rescue the people they thought were trapped inside the room. But there was only one occupant, and she was already dead. Jewett's body lay on the smoldering bed, charred but still whole enough to show the three wounds on her head that had apparently killed her.

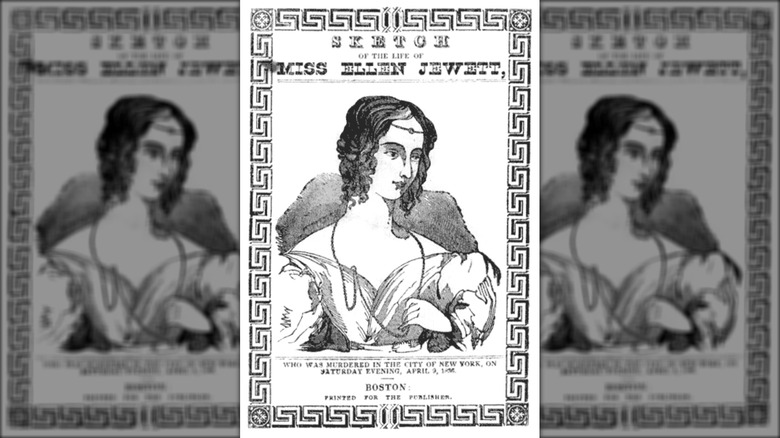

At first, no one knew who Helen Jewett was

Though the woman lying dead in her own bed was known as "Helen Jewett," that wasn't her birth name. For authorities at the time, finding out her true identity was complicated. For one, per the NWSA Journal, Helen had a tendency to lie about her past. She told some people that she was really Maria Benson, an orphan who had fallen into immorality after being seduced by a Boston merchant's son. But this story appears to have been a convenient fiction to generate sympathy, playing into moral sensibilities that assumed innocent young women were prime targets for sexual corruption.

According to "The Murder of Helen Jewett," the police didn't seem that interested in uncovering the dead woman's identity. From their perspective, it may have been more useful that she remain a beautiful murder victim to motivate the public to track down her killer. Finding the real "Helen" may have produced an inconvenient backstory.

The truth was that neither Maria Benson nor Helen Jewett was the correct name for the murder victim. Rather, she was actually born Dorcas Doyen in Maine in 1813, according to ThoughtCo. She was indeed orphaned fairly young and later lived with a prominent local judge who attempted to raise her. Eventually, she made her way to New York City, where she changed her name to Helen Jewett and got involved in sex work.

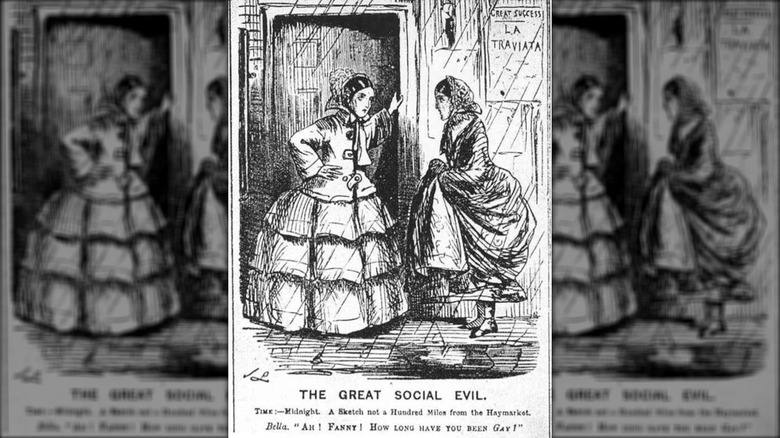

Helen Jewett was part of a new group of women

Though Helen Jewett's story became widely known in the United States, she wasn't the only woman to cast off conventional morality and strike out on her own. In fact, there were enough women in similar situations that the assembly of early 19th century women engaged in sex work became known as the "frail sisterhood." According to the NWSA Journal, this sisterhood was composed of women who were free from the bonds of typical 19th century American life. They were not subject to the paternalistic structure imposed by families or employers who sought to structure their lives, as women in other workplaces found to be the case. Instead, the frail sisterhood represented women who — though still operating within a male-centric patriarchy that turned their bodies into commodities — were at least managing lives of their own.

The frail sisterhood wasn't restricted to the bustling northeastern cities, either. As Smithsonian Magazine reports, sex workers in Nashville had a considerable presence before and during the Civil War, to the point where occupying Union forces saw them as a serious problem that spread disease and undermined troop morale. The women themselves likely worked out of economic necessity, not unlike many of their northern counterparts. Although they were clearly an integral part of their community, they remained the subject of moralistic horror.

Helen's murderer was identified as Richard Robinson

According to "The Murder of Helen Jewett" (via The New York Times), the last known man to have spent time with Helen was "Frank Rivers." Rosina Townsend recalled that Helen had ordered champagne for herself and her visitor the night of her death. Townsend brought the bottle and two glasses up to Jewett's room and saw the man in bed there. Given that no one else had come to see Helen that evening and that "Rivers" seems to have disappeared sometime before the night's chaos, attention naturally turned to him.

Shortly enough, investigators tracked him down. He was, of course, no Frank Rivers, but a young clerk named Richard P. Robinson. Not only did he fit the description of Jewett's last customer, but he lived just a half mile south of the brothel in a Manhattan boarding house. He also had white marks on his pants, which some took to be stained from a whitewashed fence near the brothel that the assailant had scaled. Police collected the young man and took him back to the brothel, even allowing him to view Jewett's remains in the hope that the sight of her corpse would shock him into revealing the crime. Robinson remained stoic, but it still wasn't enough to clear his name. The testimony of the women within the brothel as well as that of Robinson's roommate, James Tew, was enough to send him to jail to await trial for murder.

Richard Robinson was looking to shed his old life

Richard Robinson was a surprising murder suspect. As "The Murder of Helen Jewett" (via The New York Times) recounts, he was from a well-off family and his father was a Connecticut legislator. Robinson himself told police that he was a young man of "brilliant prospects" who would not ruin his promising life by murdering a sex worker. Though it was not enough to avoid prosecution, this reputation would later introduce serious doubts in deciding the verdict of Robinson's trial.

According to ThoughtCo, he had benefited from a good start in life back in Connecticut, receiving a decent education before packing his bags for New York City. He even went by a new name, the aforementioned "Frank Rivers," which was his preferred pseudonym when he went to the brothel. Yet, as exciting as a new life and freedom from family oversight may have been, Robinson's escapades in New York had a dark side. His companions weren't always of the most upstanding sort, for one. After having met Helen Jewett when he was a teen — some accounts claim that he saw Jewett being accosted at a theater and struck up an acquaintance there — the two proceeded into an on-again, off-again relationship.

The people involved didn't fit stereotypes

Being a sex worker in the 1830s in New York City was complicated, and women were not only at risk of violence but also faced societal disadvantages. Historical Archaeology notes that women in the rough Five Points neighborhood just a decade later faced serious economic issues much like their non-working counterparts, even though they attempted to put a genteel face on things for customers.

But even though tough times were hard to escape and Helen Jewett was one of many sex workers in the city, something about her death stood out to newspaper reporters and editors. They couldn't let her story sit idle. According to the NWSA Journal, one editor even entered the crime scene and scoped out the books next to her bed, helping to build the image of Helen (whose name was sometimes misspelled as "Ellen") as an educated woman.

Helen, who was reportedly considered to be quite the beauty, was now being constructed as an intellectual, too. It wasn't just that she was well-read and well-spoken: She knew how to write as well. According to "The Murder of Helen Jewett," this was proven when letters exchanged between Jewett and Robinson were discovered. Though their prose was undeniably purple at times, it was clear that both knew how to deploy metaphors and dig deep into the English language to impress the other. Eventually, the rest of the American public took notice as well.

Tabloids fed off and generated shock about the case

The way in which the Helen Jewett murder was covered in newspapers attempted to balance a sense of Victorian Era morality and the widespread fascination with lurid sexuality. But it might have still faded into history if it weren't for newspapers. According to the NWSA Journal, it was the New York Herald newspaper that first dug into the case, publishing the tale in cheap editions that were easily accessed across the city. However, as ThoughtCo reports, there was little attempt to maintain journalistic integrity. Stories were exaggerated or even fictionalized outright. Even the articles that had some claim to the truth were written in such a way that they whipped many readers into a frenzy.

The New York Herald and other tabloids also took plenty of opportunities to speculate on Richard Robinson's motivations. As Encyclopedia.com notes, there was some evidence that he may have been embezzling money from his employer, which he could have then been spending on Jewett. However, information about the financial state of Robinson or his workplace was scanty at the trial itself. Other sources claimed that Jewett threatened Robinson after hearing rumors of his impending marriage to another woman. Either way — and regardless of petty things like the truth or journalistic integrity — the New York Herald and its ilk gained serious exposure and income by publishing piece after piece delving headfirst into the case (via ThoughtCo).

Robinson was quickly put on trial

Richard Robinson's fate was far from certain. Was the young store clerk, son of a respectable landowner and state lawmaker, really the murderer?

According to Encyclopedia.com, Robinson's trial began on June 2, 1836, and lasted until June 7. His employer, store owner Joseph Hoxie, hired a well-known lawyer to defend the young man. Stirred up by the newspaper-fueled frenzy, a crowd of about 6,000 flooded the courtroom. The scene was difficult for Judge Ogden Edwards to control, even with the help of additional security. When only a portion of the jury members appeared, people from the crowd were drafted to fill in.

When the trial finally got underway, several details of that night came under scrutiny. The district attorney questioned brothel keeper Rosina Townsend, who said that Helen Jewett's usual client for that night was a man named Bill Easy. However, she remained firm that Robinson was the man who was last known to be with Jewett on the night of her death. Some witnesses also noted that the hatchet used to kill Jewett was much like the one used to open crates at Robinson's store, though others claimed that Jewett's fellow sex workers were attempting to frame him. Other bits of circumstantial evidence proved interesting but never quite definitive. Perhaps the most damning would have been threatening letters supposedly sent by Robinson, but the defense was successful in keeping those letters from being read aloud in court.

Helen's story challenged 19th century attitudes about sexuality

Like in so many eras before and after, 19th century America was a complicated time to be a woman. "Good" women of the time were often expected to be compliant domestic figures who lived only to take care of their family, transforming into the "angel in the house." Yet, as PBS notes, women in the U.S. were rarely afforded the opportunity to sit meekly at home. Most had to work to support themselves and their families. In the antebellum period, about half of all women worked, though most were obliged to quit once they married. Some were tempted to leave poorly paid "legitimate" work, bucking the modest sexual norms of the period to become sex workers.

As the NWSA Journal notes, most Americans at the time assumed prostitutes were uneducated. Yet Helen Jewett, who was not only beautiful but intelligent and accomplished, seemed out of place. What's more, the testimony of the Maine judge who had taken her in seemingly made it clear that Jewett had the opportunity to take on other types of work. What did it mean that she left it all behind and moved to New York City for a life of apparent sin? Partially or even completely fictionalized narratives painted her as a once-moral fallen woman, concluding that independent and overtly sexual women were doomed. But the subtleties of Jewett's life complicated this narrative.

Robinson was acquitted

Many people began to take sides during Richard Robinson's trial. As the NWSA Journal notes, some New Yorkers began to wear hats and ribbons proclaiming their sympathy for either Robinson or Helen Jewett. Reports hinted at Jewett becoming quite a legendary figure, with women flocking to her bed when it was left on the street and taking away talismanic pieces of charred wood.

But not everyone was convinced that Robinson was a murderer. Though the closing arguments in the trial sprawled on for more than 10 hours, the jury — which was biased because some members personally knew Robinson's witnesses — moved quickly. After a 15-minute deliberation, the jury declared Robinson not guilty. He was released, and no other people were ever brought under scrutiny for the death of Helen Jewett (via Encyclopedia.com). The case remained unsolved.

Suspiciously changing his name to "Richard Parmalee" after the trial, Robinson left town and traveled to Texas. According to "The Murder of Helen Jewett," he married and moved to the town of Nacogdoches. His 1845 marriage brought him financial stability while he also achieved social recognition, becoming one of the wealthiest people in the area. He died in 1855 while traveling the Ohio River, with some of the more lurid tales alleging that he uttered Jewett's name on his deathbed. Whether or not that really happened, Robinson's remains were shipped back to Nacogdoches and buried there in December 1855.

After the trial, Helen Jewett's story still drew attention

According to Timeline, medical students exhumed Helen Jewett's remains just a few days after she was buried in St. John's cemetery. They then dissected Jewett's body and turned her into what the New York Herald deemed an "elegant and classic skeleton."

Tales of Jewett's beauty, her violent death, and the trial that followed were churned out by cheap penny presses for years afterward (via NWSA Journal). Charles Sutton, warden of the New York Tombs, colorfully recalled Jewett in his 1874 memoir, "The New York Tombs." Many decades after the real woman walked through the streets of Manhattan, Sutton recalled her in inflated terms. She was "radiant," the "queen of the demimonde," who moved amongst the dull people around her as if she were a "silken meteor." Of course, like so many people of the era, Sutton had to wrap it all up in a moral bow, proclaiming that it was tragic that such a beautiful woman was so morally corrupt.

Many small chapbooks purported to tell her tale, though a significant number took liberties with the story, as the NWSA Journal attests. So, too, did a florid dime novel and three 20th century novels, including one that at least had the decency to present itself as fiction. Even now, though people's morals may have shifted, they are still captivated by the dark story and the media frenzy that grew around Jewett's murder.