The Messed Up History Of Yellow Journalism

In the late 1890s, people started describing a particular type of news. Often, it was stylized in a particularly loud manner, with flashy and sensationalized headlines, and more often than not the stories had been hyperbolized beyond recognition. Referred to as "yellow journalism," this type of journalism emerged mainly because two newspaper publishers in New York City were competing for circulation.

Since the reporting was often reckless and unsubstantiated, the expression ended up sticking to describe "irresponsible reporting." Today's "fake news" finds its roots in yellow journalism as the line between publisher and platform grows fainter and fainter. However, the journey from yellow journalism to fake news isn't a smooth one, for there are multiple aspects of news media today that have evolved from yellow journalism.

Yellow journalism also wasn't solely a United States phenomena. Mexico saw its fair share of yellow journalism at the beginning of the 20th century, and when newspapers reported that Benito Mussolini was ill in 1925, he derided them as the "yellow press." This is the messed up history of yellow journalism.

What is yellow journalism?

Yellow journalism was often recognized by several defining factors. Frank Luther Mott, a media historian, notes that yellow journalism often used a plethora of pictures, often insignificant ones, interviews which were fake, and loud headlines that "screamed excitement." And according to Yellow Journalism, by W. Joseph Campbell, many of the qualities of yellow journalism, such as its Sunday supplement and banner headlines, "had a lasting effect on the American press" and can still be recognized in modern journalism.

However, Campbell also notes that Mott underlined the fact that yellow journalism was not necessarily "synonymous with sensationalism." In an effort to self-promote and call attention to themselves, papers often embarked on crusades against corruption and monopolies, which Mott described as "sympathy with the underdog." Campbell himself notes that this resulted in a variety of investigative stories, as well as a variety of topics ending up on the front page. Publishers also greatly experimented with layout designs and included various illustrations ranging from maps to photographs.

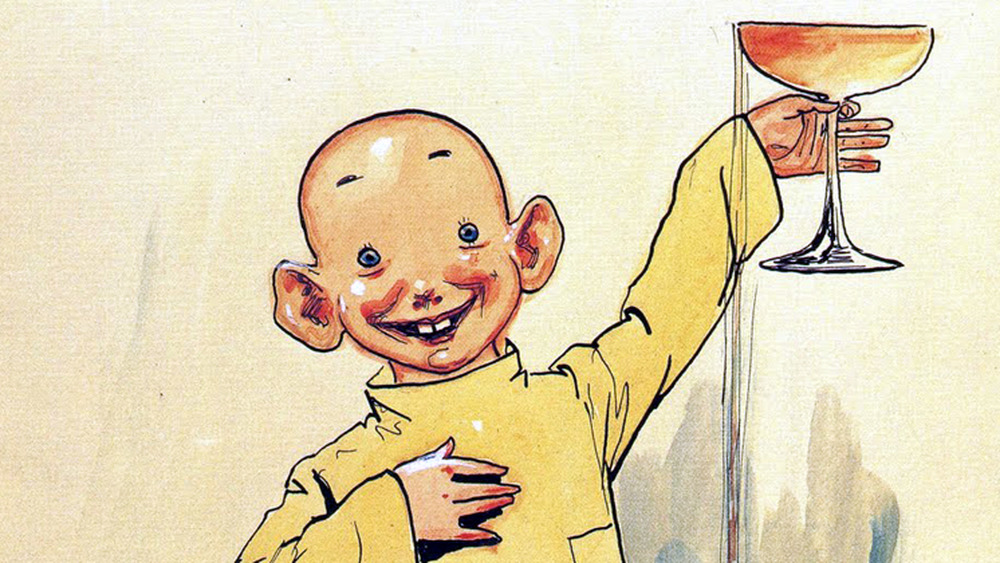

The term was reportedly coined by New York Press editor Ervin Wardman, who initially played with the expressions "new journalism" and "nude journalism." But in January 1897, he settled on "yellow-kid journalism," which would later be abbreviated to become the "yellow journalism" known today.

What started yellow journalism?

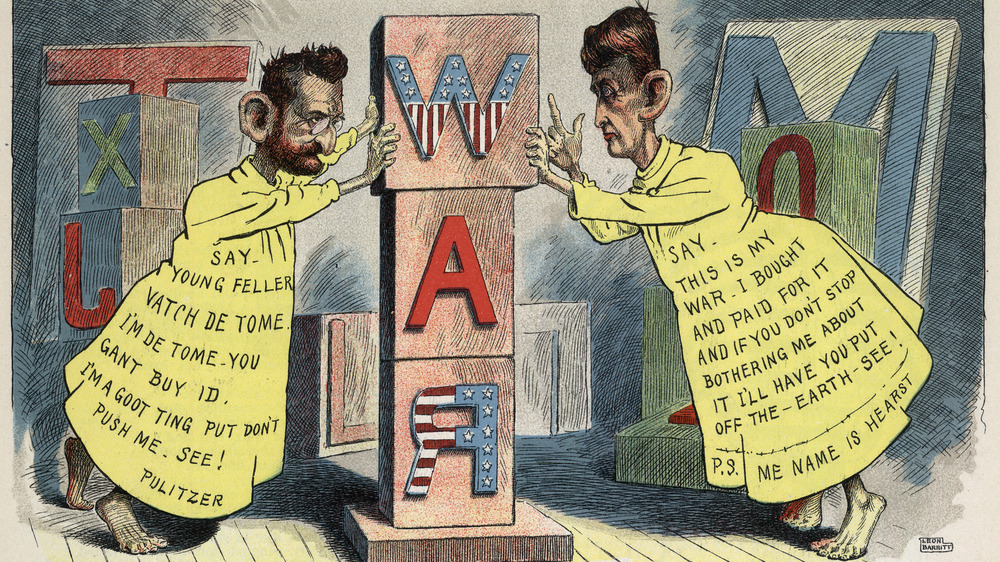

Yellow journalism was actually spearheaded by two of the most famous newspapers in New York — Joseph Pulitzer's New York World and William Randolph Hearst's New York Journal. According to ThoughtCo., after Hearst bought the New York Journal in 1895, his primary concern was beating Pulitzer's New York World. Sometimes, this was done simply by offering Pulitzer's writers and cartoonists more money to go work for the New York Journal instead.

But another method of Hearst's involved one-upping Pulitzer's editorial style, which included the enticing (and sometimes sensationalist) headlines and crime stories. And as Pulitzer responded in turn, soon the papers were publishing facts that were embellished to such a degree that eventually the credibility of both papers were lost among readers. The Office of the Historian notes that while the publishers never fabricated events, they weren't above stoking prejudicial sentiments and publishing rumors as long as papers sold. Hyperbole was also especially useful.

While propagandized news was certainly around before this time, since the two papers had such a large circulation, the sensationalist news was able to capture the public in a way that had never quite been seen before in the United States.

The Yellow Kid

The fight over sensationalist news actually stemmed from a cartoon, which is where the "yellow kid" of "yellow-kid journalism" comes from. According to PBS, the New York World had a cartoon called "Hogan's Alley," which included a character known as "the Yellow Kid."

Although the racist ideology of "the yellow peril" emerged around the same time, it doesn't seem as though the Yellow Kid was related or meant to be a racist caricature. Instead, the "yellow" was meant to refer to his costume, which was "always yellow." According to the University of Virginia, the cartoon attempted instead to "mock all classes ... offering a safe environment to laugh at American foibles, while still excluding African-Americans from the joke."

Up until October 1896, "Hogan's Alley" was created by artist R.F. Outcault and printed in Joseph Pulitzer's New York World. But then, William Randolph Hearst recruited Outcault and got him to bring the Yellow Kid with him. However, although Outcault attempted to copyright the Yellow Kid, he was unsuccessful, and Pulitzer was able to hire George Luks to take over "Hogan's Alley."

Even though Outcault's version was still favored by the public, by 1898 the Yellow Kid stopped appearing as a regular character altogether. W. Joseph Campbell suggests that this was a result of the sinking reputation of yellow journalism, which many believed was responsible for causing the Spanish-American War. Outcault himself was implicated in this, since as early as 1896, his cartoons were featuring an occasional "Viva Cuba Libre" and "free Cuba."

Did yellow journalism start the Spanish-American War?

Although some claim that the New York World and the New York Journal's yellow journalism was responsible for the Spanish-American War, that might be giving them more credit than they're due. While the papers certainly fueled anti-Spanish sentiments among Americans, these prejudices were already there, and the papers merely "[reflected] Americans' anger at Spain's treatment of Cuba" (via the University of Virginia).

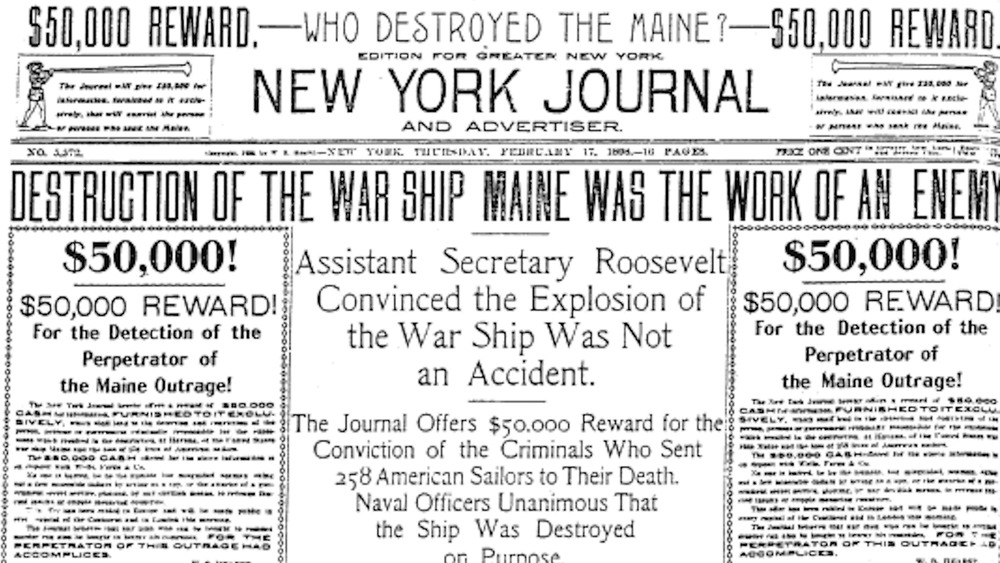

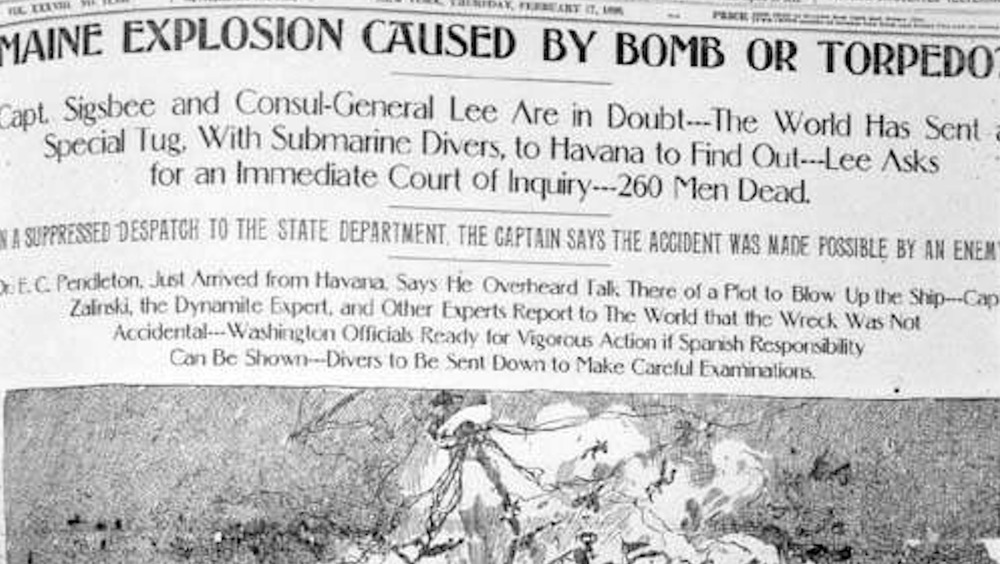

National Geographic also writes how Joseph Pulitzer and William Randolph Hearst were both responsible for publishing a fake story that claimed Spain was responsible for sinking the U.S.S. Maine in Havana Harbor. Since the story was so sensationalized and hyperbolized by both publishers, it stayed in the public's minds and "those recollections helped push the country to war several months later."

But according to the University of Virginia, neither of these papers were vying for an actual war to occur. The war itself wasn't profitable for the papers. "It drove away advertisers, newsprint costs skyrocketed, and it was expensive to pay for war coverage." Even when the New York Journal ran the headline, "How Do You Like the Journal's War?" for three days, in May 1898, it was meant to mock the notion that they were responsible for the war. "They were certainly not serious claims of responsibility for instigating the war," W. Joseph Campbell writes in Yellow Journalism.

However, even if the headline was "tongue-in-cheek," neither paper can deny the fact that their personal war over profits was "instrumental in getting the U.S. involved" in the Spanish-American War.

The telephone game of news

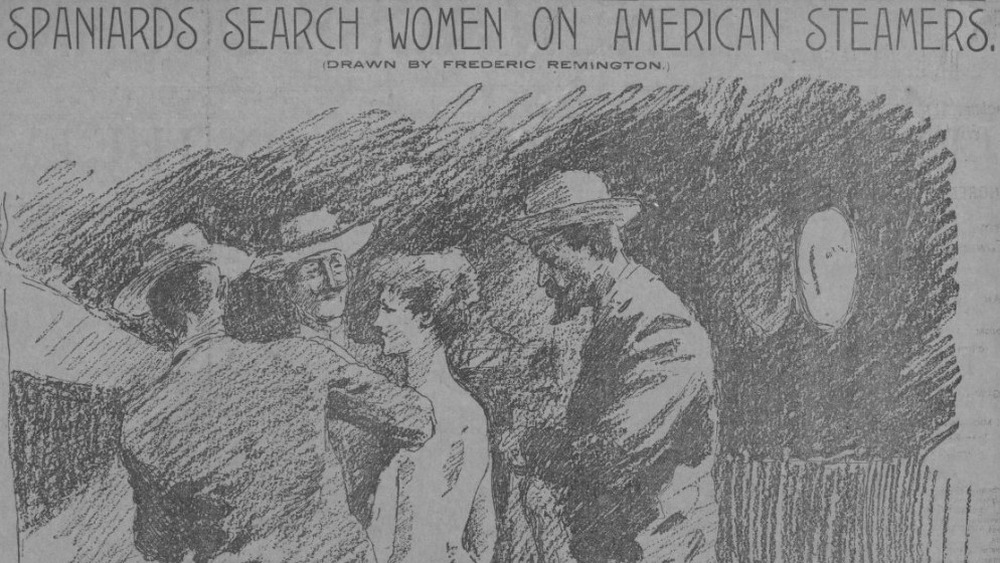

Although stories were often embellished, they were often based on a foundational truth. According to National Geographic, one such example of a sensational story was Richard Harding Davis' reporting.

Davis worked for the New York Journal as a war reporter in Cuba, but since the Spanish Gen. Valeriano Weyler abhorred the American press and had begun throwing journalists into jail, Davis decided to return back to the United States in 1897. On the way, he encountered Clemencia Arango who, according to The Year That Defined American Journalism, by W. Joseph Campbell, was being expelled from Cuba by the Spanish "because of her ties to the insurgents."

Arango recounted to Davis how she and her two companions had been searched for secret messages by the Spanish authorities before boarding the ship. Although the women were in fact carrying secret messages, which hadn't been discovered, Davis neglected to mention this in his written account.

Instead, Davis dramatized to the point where, by the time they'd gotten to New York, the story had evolved to necessitate an illustration of a naked woman surrounded by three inspectors. In actuality, the three women had been searched by women, and the search was done "behind closed doors, not in plain sight above deck."

Who was James Creelman?

James Creelman was a "quintessential practitioner of Yellow Journalism," writes Martin J. Manning and Clarence R. Wyatt. He was willing to do anything to get the best story, and some of his stories exposing fraud actually led to legal or government action.

And the Spanish-American War wasn't the only foreign affair that yellow journalism got involved with. According to The Tequila Files, Creelman was partly responsible for sparking the Mexican Revolution, albeit inadvertently. In 1908, President Porfirio Díaz granted Creelman an interview, where he defended the existing one-party system. And when Díaz claimed, "I have so many friends in the republic that my enemies seem unwilling to identify themselves with so small a minority," he ended up unintentionally galvanizing his rivals.

Creelman was unapologetic about yellow journalism, considering it essential towards revealing the truth hidden by governments. In his book, On the Great Highway, Creelman writes, "As one of the multitude who serviced in that crusade of 'yellow journalism,' and shared in the common calumny, I can bear witness to the martyrdom of men who suffered all but death — and some, even death itself — in those days of darkness. It may be that a desire to sell their newspapers influenced some of the 'yellow editors,' just as a desire to gain votes inspired some of the political orators. But that was not the chief motive; for if ever any human agency was thrilled by the consciousness of its moral responsibility, it was 'yellow journalism' in the never-to-be-forgotten months before the [Spanish American War]."

The pioneering editor of yellow journalism

Yellow journalism wouldn't be complete without yellow editors, and Arthur Brisbane was one of the best. Working initially as a journalist, Brisbane first worked for Joseph Pulitzer and then joined William Randolph Hearst at the Journal. He was one of the many employees of Pulitzer, including Creelman, who was eventually recruited or defected to Hearst.

According to Chicago Magazine, Brisbane knew that mysterious and murderous stories would sell, so he milked those stories for all that they were worth. And even when Pulitzer complained that Brisbane was turning his journal into "a Victorian scandal sheet," Brisbane pointed out how much more money they were making. At the Journal, Brisbane worked as an editorialist and later moved on to editing.

Brisbane himself believed that yellow journalism was necessary for furthering social change. He argued that, "the whole human race, according to the highest authority, has been exterminated once already because it wasn't going right and only the rainbow protects it from a repetition. They say the Hearst papers are Yellow. Remember that the sun is Yellow and we need a little sunshine. Think of the colors of the rainbow."

Brisbane ended up staying with Hearst for the rest of his life and defended his employer through thick and thin, although he was noticeably silent about Hearst's affair with actress Marion Davies.

Nellie Bly sensationalizes scandal

Another prolific reporter was Nellie Bly, who worked for Joseph Pulitzer as an investigative journalist. She often jumped head-first into a story, the most famous of which was her exposé on the conditions at the New York City Mental Health Hospital on Blackwell's Island.

Mental Floss writes how in 1887, for one of her first articles for the New York World, Bly got herself committed and spent ten days in the hospital for a story. Her resulting series of articles, titled "Ten Days in a Madhouse," detailed the inhumane treatment by the doctors, the forced isolation, and the rotten food. "What she found exceeded her worst expectations." Some of the women there were also completely sane and had only been committed because they were foreign, and the doctors refused to try to communicate with them.

After the article came out, Bly was commended for inspiring the city's committee of appropriation to give an extra $1 million dollars for mental health treatment. Even though the consideration for additional funding wasn't new, it's safe to say that, "Bly's article certainly pushed things along."

According to Biography, in 1889, Bly was sent by the New York World on a trip around the world to test Jules Verne's 80-day fictional trek, and she set a record by circling the globe in 72 days. But many of Bly's pieces focused on corruption and the poor treatment of workers and imprisoned people. She also conducted interviews with many notable figures, such as Emma Goldman.

The beauty of being blatantly wrong

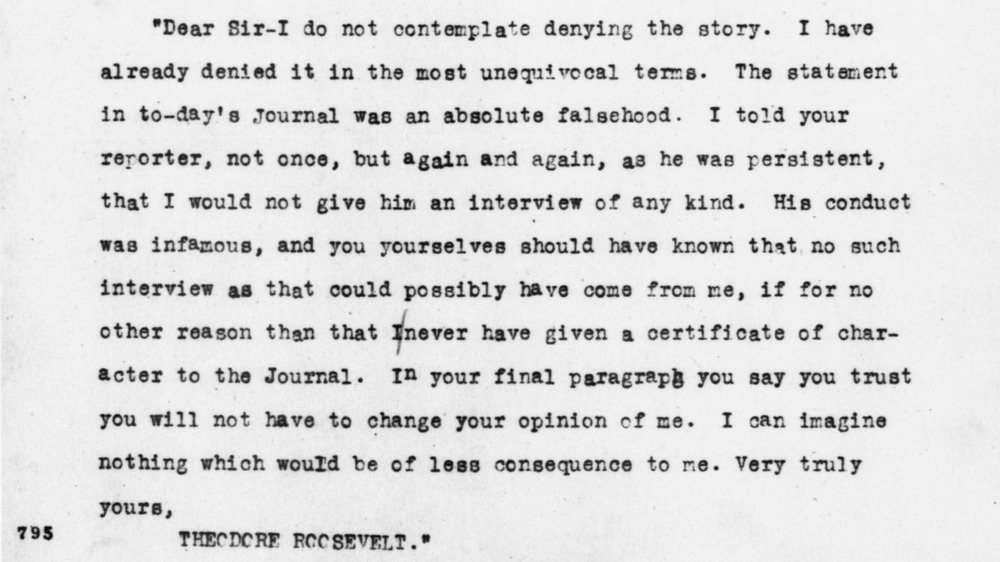

Although yellow journalism had its investigatory qualities, sometimes the stories printed were unsubstantiated or had blatant errors, such as the story about the U.S.S. Maine. At one point even Theodore Roosevelt, who was assistant secretary of the Navy at the time, was forced to get involved.

According to the Theodore Roosevelt Center, after the New York Journal published an interview that they claimed was conducted with Roosevelt, the real Roosevelt put out a statement in the New York Sun that said the interview was an "invention from beginning to end." Roosevelt insisted that the interview had never occurred and was completely made up by the Journal.

Although only journalist M.S. Peters, Jr., and Roosevelt himself know for certain whether or not the interview was a fabrication, neither story is entirely unlikely. Roosevelt had a habit of testing ideas through journalists and denying the story if the public reaction was negative, so it wouldn't be unexpected for him to deny the interview given the public perception of the Journal. However, the interview also claimed that Roosevelt said that the Journal's coverage was "most commendable and accurate," so it's also likely that the Journal was simply hoping to give itself some undue credibility.

Offered solutions to yellow journalism

Yellow journalism was disliked for a number of reasons. Since yellow journalism wasn't always necessarily fabricating everything, it became incredibly difficult for the public to discern what was and what wasn't evidence-based news. Others simply didn't like the fact that William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer were making so much money. So, in response to the escalating yellow journalism, there were several ideas suggested to combat its spread.

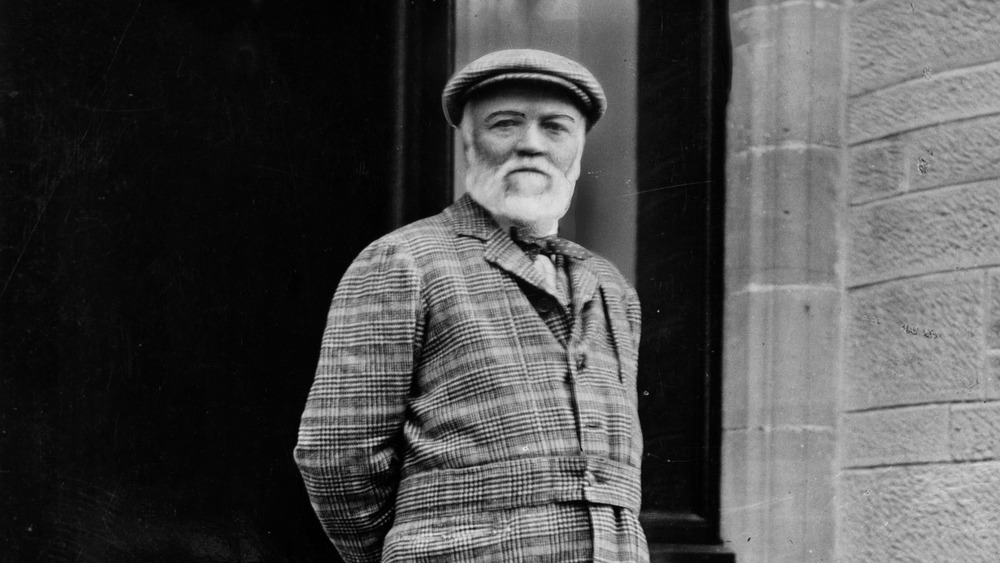

According to The Yellow Journalism, by David R. Spencer, one suggestion involved creating endowments for journals, with the idea that "if one freed the press from the basic need to attract advertisers, the quest for constant circulation increases could be dealt with." Some, like steel magnate Andrew Carnegie, simply wanted to limit the profits of Hearst and Pulitzer, and when the endowment plan didn't come to fruition, there was an attempt to simply "buy out both Pulitzer and Hearst."

However, all of these plans failed, and yellow journalism continued to thrive. However, in September 1901, it "finally reached the zenith of its role as gossipmonger, social critic, and disturbing influence."

Going too far?

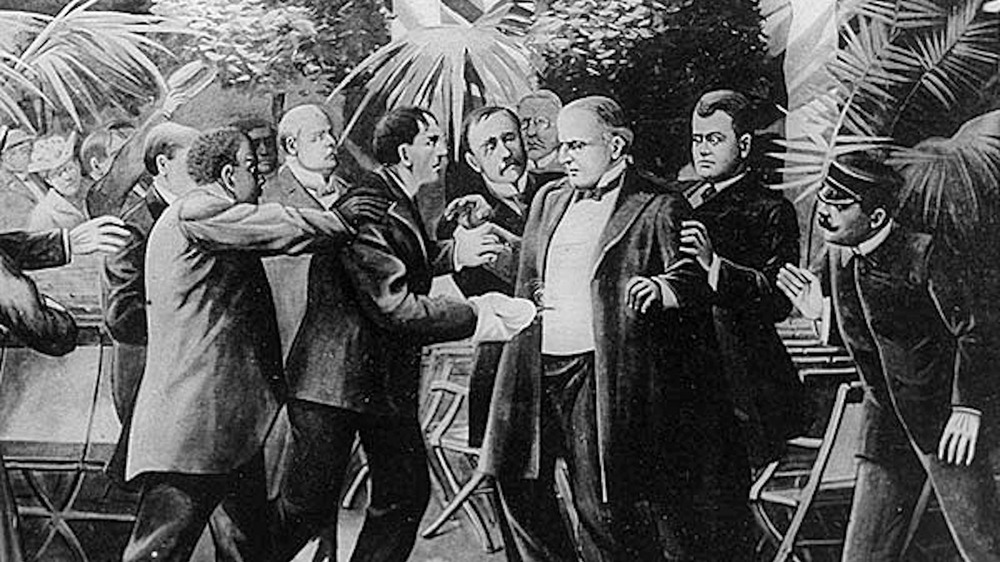

While President William McKinley had been campaigning for his second term, William Randolph Hearst had openly backed his opponent William Jennings Bryan and set out to alienate his readers from both McKinley and the Republican Party.

According to The Yellow Journalism, a satirical cartoon series called "McKinley Minstrels," by Frederick Opper, was a frequent mocking feature. But after McKinley was assassinated by Leon Czolgosz just months into his second term on September 1901, everyone started blaming Hearst and the Journal.

It didn't look great that during the campaign, a column by Ambrose Bierce, as well as another one thought to be by Arthur Brisbane, seemed to propose McKinley's assassination, writing that, "if bad institutions and bad men can be got rid of only by killing, then the killing must be done." It also didn't help that a rumor spread that a copy of the Journal was in Czolgosz's pocket at the time of the assassination, even though Czolgosz himself said that he was inspired by Gaetano Bresci, an Italian anarchist who assassinated King Umberto I in 1900, just the previous year.

Hearst attacked his detractors in turn, and although his media empire was able to survive, "Yellow Journalism, which eventually gave way to different forms of activist journalism such as muckraking, never commanded the heights that it once did after the twentieth century dawned on Park Row."

Yellow journalism evolves into muckraking

Since some of the scandals that people were sensationalizing were in fact actual crimes of corruption or abuse, after President William McKinley's assassination, yellow journalism reined in its instigative nature. Expanding its investigative side instead, muckraking evolved out of yellow journalism. While the New York Journal and the New York World were famous for their yellow journalism, journals like McClure's Magazine were famous for muckraking.

The word comes from the fact that President Theodore Roosevelt described journalists as "raking the muck," or filth, of society. However, he said they were indispensable "only if they know when to stop." The idea of muckraking itself comes from John Bunyan's novel, The Pilgrim's Progress from This World, to That Which Is to Come, where he describes the Muck Rake, "the man who could look no way but downward," constantly raking the filth on the ground.

Oxford Bibliographies writes that muckraking entails investigative journalism that is particularly focused on "subjects of importance of society." While yellow journalism was concerned with titillating and sensationalist stories in the vein of modern tabloid journalism, muckraking was concerned with bringing down government corruption and corporate power. And according to The Muckrakers, by Louis Filler, "muckraking was literary rather than 'yellow,'" and those who tried to claim it were often pointed to Charles Dickens, "who had also been attacked as being no 'artist.'"