Small Details You Missed In Vincent Van Gogh's Most Famous Paintings

Vincent van Gogh made a career of producing vibrant, dappled, swirling, and primitive artwork before it was cool. However, he paid a hefty price for it, exiled to obscurity throughout his lifetime, per Biography.

Sure, the Impressionists had already paved the way for artwork veering away from traditional realism, as per Britannica, but van Gogh took things to the extreme. In the end, his artwork still seems to divide people between two camps: love and hate. Consider the case of the Twitter user Megha, a self-proclaimed art teacher, who recently declared van Gogh "overrated."

That said, the ginger artist known for his love of sunflowers and brothels (by his own admission, per the BBC), left plenty of intriguing details in his artwork. Some still boggle scientific minds more than a century later, and others offer fascinating insights into the environments and conditions where he painted. Here's everything you need to know about small details worth a second look in van Gogh's most famous paintings.

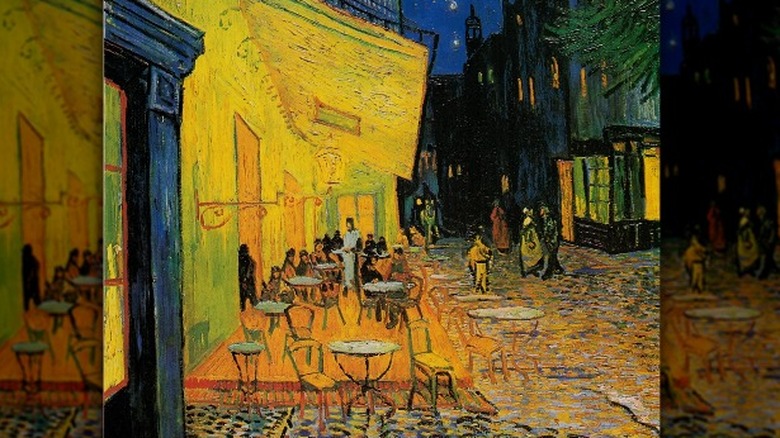

Café Terrace at Night, 1888

Ever since 2006's "The Da Vinci Code," people have scoured Leonardo da Vinci's masterworks in search of hidden mysteries. But it would take the extraordinary observation skills of researchers like Jared Baxter to uncover linkages between Da Vinci and Vincent van Gogh, per the HuffPost. Baxter claims that one of van Gogh's most celebrated canvases, "Café Terrace at Night," contains a religious easter egg. Some scholars have gone so far at to rename the work "Van Gogh's 'Last Supper'" (via Jared Baxter's "Van Gogh's Last Supper: A Nonfiction Book Proposal").

In the painting, the café is awash in yellow and lime-colored light beneath a periwinkle sky, pulsing with stars. As the Huff post detaisl, in the background, you'll notice a group of figures left of center. Seated or standing on the outside terrace of the café, there's a total of 12. That's the same number as Jesus plus his disciples minus Judas Iscariot, the betrayer. While it might rattle some cages to think of van Gogh appropriating iconography from religious artwork to suit his own purposes, it's not far-fetched.

Van Gogh didn't become an artist until his late 20s, as reported by the Van Gogh Museum. Before that, he held a few other occupations, including work as a minister. And he was no adherent to the so-called "prosperity gospel" — what Vox notes ties wealth with Christianity. Instead, he served in a coal mining town, expressing a sincere devotion that earned him the nickname "The Christ of the Coal Mine" because of his ascetic lifestyle and generosity.

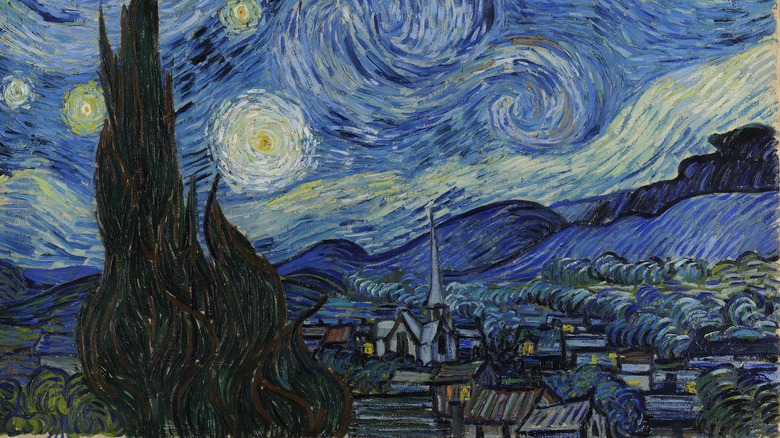

The Starry Night, 1889

The swirling firmament of the "The Starry Night" has arrested audiences for centuries with its mystical depictions of heavenly bodies and twinkling stars. In contrast to this tumultuous canvas is a peaceful and sleepy village in the middle ground, per the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). In the foreground, evergreen trees rise in twisting spires, creating a jutting skyward motion drawing the eyes back into the multi-hued blue waves of the sky. A traditional perspective on this painting argues that the swirling atmosphere represents a kind of emotional mirror reflecting back Vincent van Gogh's inner feelings, as per the Irish Times.

But there's a lot more to those swirling patterns than a projection of inner emotions on the outer world, per The Culture Trip. In 2004, the Hubble Telescope captured a phenomenon known as stellar turbulence. No matter what you call it, researchers realized they'd seen something similar before: van Gogh's "The Starry Night."

Further examination revealed van Gogh depicted the phenomenon with astonishing accuracy. How he did this remains open to speculation. According to The World, van Gogh may have been inspired by a scientific drawing published in the mid-19th century by William Parsons: nebula M51 or the "Whirlpool Galaxy." Parsons created the image using a highly powerful telescope. Eventually, it appeared in a book by Camille Flammarion sold in France where van Gogh spent much of his artistic career.

The Potato Eaters, 1885

Vincent van Gogh's "The Potato Eaters" stands apart from his other works. According to the Van Gogh Museum, for starters, it relies on a dull palette, which he wrote was reminiscent of the color of a "really dusty potato, unpeeled of course." This choice of colors communicates the impoverished living conditions of its subjects and their humble meal of potatoes and coffee. The artist also sets concerns about anatomical correctness aside in favor of conveying the harshness of their life of manual labor, forever bound to the earth and its bounty.

As Smithsonian Magazine points out, van Gogh spent an uncharacteristic amount of time involved in sketches and studies to prepare for the creation of this masterpiece. All told, he created 50 sketches and paintings on the subject. The people in the painting are members of the de Groot-van Rooij family, and they allowed the artist into their home numerous times as he worked on the concept (via The Art Newspaper).

Among the small details worth noting in this piece (apart from the color scheme) is the way van Gogh portrayed the family's hands and faces. They are large and rough like the terrain they labor upon. According to The Guardian, the faces of the family members also contain revelatory expressions. For example, the young woman on the left side of the canvas looks at her husband with both longing and reverence, a simple yet passionate avowal of uncomplicated love and devotion.

The Courtesan, 1887

Some details found in Vincent van Gogh's canvases require a little extrapolation to better understand than others. For example, you don't need an art degree to notice the look of love found in "The Potato Eaters." But other symbols and clues require a firm grasp of 19th-century French culture.

For example, "The Courtesan" immediately communicates van Gogh's appreciation for Japanese Ukiyok-e woodblock prints, as reported by the Economist. This particular iconography was inspired by Kesai Eisen's cover of the "Paris Illustré" magazine, which appeared on newsstands in May 1886, as per the Van Gogh Museum. While you're hit over the head with the Japanese esthetic, smaller details can easily go overlooked.

The pond imagery bordering the piece contains some telltale symbology. Notice the white cranes on the lefthand side, and the frog at the bottom of the work, sitting on a lily pad. These are more than fanciful additions to his whimsical canvas. They speak boldly of prostitution, according to the Economist. The French terms for frogs and cranes were also used as slang to describe ladies of the night. These symbols represent a decidedly Western nod to Japanese art, which had become increasingly popular during the preceding decades.

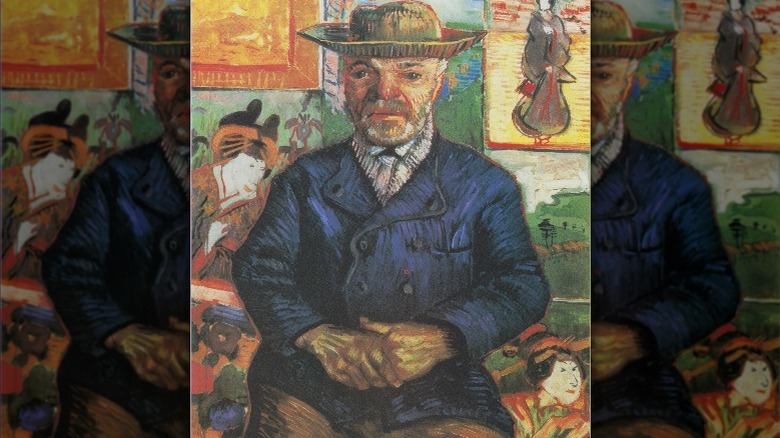

Portrait of Père Tanguy, 1887-1888

"The Courtesan" isn't the only Vincent van Gogh painting that evidences a passion for Japanese artwork, according to Ingo Walther's "Vincent van Gogh: The Complete Paintings." There's also the "Portrait of Père Tanguy," whose background is infused with many fascinating images from Japanese woodblock prints (Ukiyok-e). This is no surprise considering Père Tanguy's (a.k.a. Julien-François Tanguy) role in the Parisian art world at the time.

The Musée Rodin explains that Tanguy was a character of the Parisian art scene who ran a paint supplies shop and sat for three portraits by van Gogh. In his portrait painted between 1887-1888, the background is filled with fascinating details drawn from Japanese art. In fact, you'll find three essential themes, including the courtesan, the actor, and Mount Fujiyama, notes Walther.

But the details worth noting don't end there. As the Musée Rodin explains, how van Gogh chose to pose and depict Tanguy also has a lot to say about the message the painter wanted to convey, making him appear a very wise figure surrounded by the vivid colors of Japanese art that van Gogh and his brother loved to collect. In other words, Tanguy becomes the 19th-century equivalent of Pat Morita's Mr. Miyagi. It makes for a memorable statement that clearly shows some of the new artistic directions van Gogh would pursue (via The Guardian).

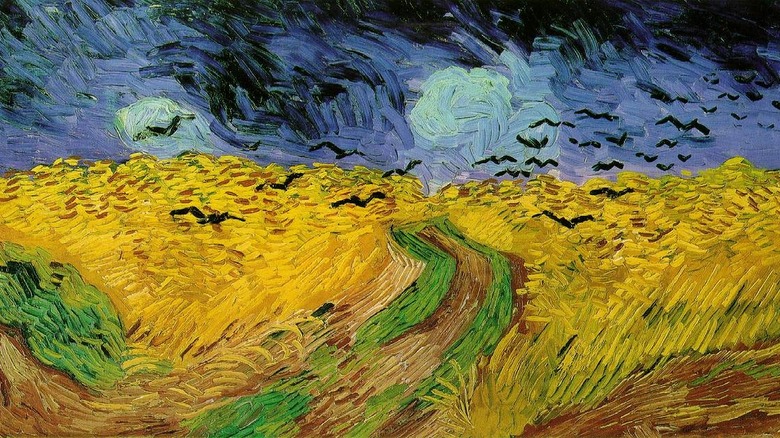

Wheatfield With Crows, 1890

Any discussion of "The Wheatfield With Crows" requires some initial debunking. According to the Van Gogh Museum, there has long been a legend that this was van Gogh's last work. These sources claim that the dead end in the middle of the canvas surrounded by crows is evocative of his impending suicide. While it sounds like a compelling idea, there's a major problem with it. The "Wheatfield With Crows" was likely not van Gogh's last painting (via The Art Newspaper).

Nevertheless, it's a masterpiece of Expressionism that provides a window into van Gogh's psyche as he proved unable to surmount the mental health demons plaguing his mind and future, as reported by The Guardian. And while this painting wasn't van Gogh's last, some say the field it depicts (or, one like it) provided the backdrop to his final act of lethal self-harm (via The Art Newspaper).

Yet, the small details of the sky's portrayal contain hints of an incomparable genius. Like "The Starry Night," the sky in "Wheatfield With Crows" portrays a real space phenomenon (unseen to the naked eye) known as turbulence with inexplicable accuracy, per the Culture Trip. These depictions were painted during times when van Gogh faced his greatest mental health struggles, as argued in "Turbulent Luminance in Impassioned van Gogh Paintings," by Jose Luis Aragon. In an interview with Nature, Aragon explained, "We think that van Gogh had a unique ability to depict turbulence in periods of prolonged psychotic agitation."

Fourteen Sunflowers in a Vase, 1888

Flowers have been a preferred subject for artists since time immemorial, and Vincent van Gogh proved no exception, per the Van Gogh Museum. But unlike many other artists of the Victorian era, he didn't reproduce diverse bouquets communicating through the language of flowers. Instead, he settled obsessively on big, splashy, sunny sunflowers. This wasn't an evident choice in the 19th century states the Van Gogh Museum.

Most painters considered sunflowers coarse, dumpy, and unworthy of the artistic spotlight. But Vincent van Gogh subverted these notions, placing the showy blossoms front and center. The results proved eye-catching, dazzling, and unforgettable. But his work with sunflowers represented more than a flower preference. These paintings allowed him to dabble in countless shades of yellow (via the Van Gogh Museum). Writing to his brother, Theo van Gogh, he explained, "The sunflowers are progressing: there's a new bouquet of 14 flowers on a green-yellow background" (as quoted by the Van Gogh Museum).

Besides the monochromatic challenge, sunflowers also expressed gratitude in the painter's mind. What's more, a careful perusal of the top of the "Fourteen Sunflowers in a Vase" painting reveals unintended details: two fingerprints where the artist picked up the canvas while still wet (via the Van Gogh Museum). These are fitting reminders of the artist in a work that represented him so personally. Fellow artist Paul Gauguin would declare these sunflower paintings "completely Vincent," and friends brought handfuls of the giant blossoms to his funeral, as per the museum.

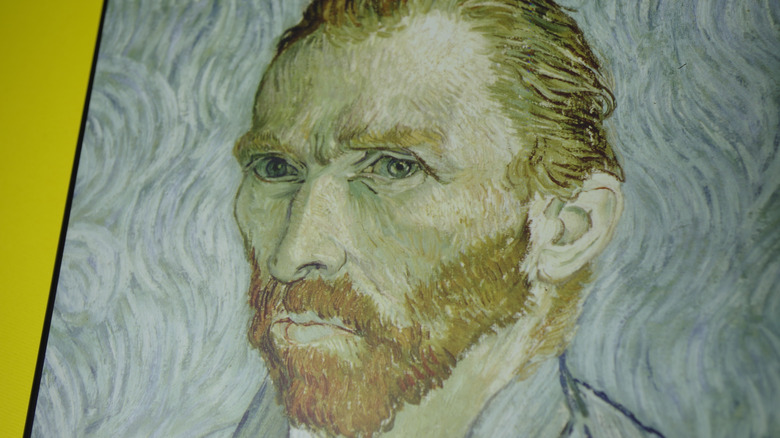

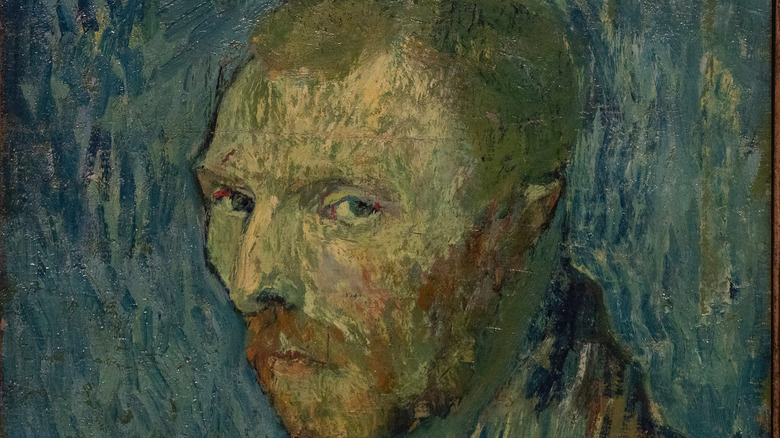

Self-Portrait, 1889

Authentication has been a long time coming for one of van Gogh's self-portraits dated to 1889, as reported by The Guardian. With the declaration that it is "unmistakably" his work by the Van Gogh Museum, art historians have scrambled for another look.

Van Gogh painted this particular portrait of himself at the asylum in Saint-Rémy, France. The background contains drab olive-brown hues quite unlike his more vibrant canvases. This palette creates a dreary vibe further underscored by the artist's uncharacteristic and tentative expression. In this case, it's the artist's blank stare that contains a vital detail. It is the stare of someone struggling with mental illness, and more specifically, psychosis.

According to Louis van Tilborgh of the Van Gogh Museum, "Although van Gogh was frightened to admit at that point he was in a similar state to his fellow residents at the asylum, he probably painted this portrait to reconcile himself with what he saw in the mirror: a person he did not wish to be, yet was" (as quoted by ArtNet). The only work by van Gogh while in this dreadful mental space, Tilborgh suggests interpreting the painting as both "remarkable and therapeutic."

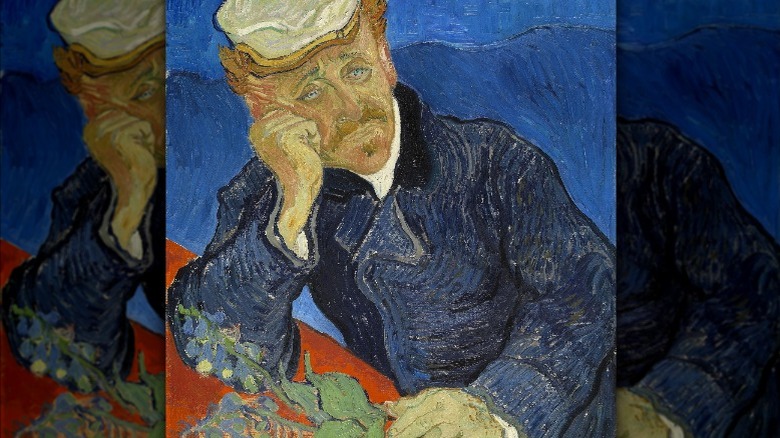

Paul-Ferdinand Gachet, 1890

After leaving the asylum at Saint-Rémy, Vincent van Gogh sought treatment from Dr. Paul-Ferdinand Gachet, whom he came to perceive as akin to him, both physically and psychologically, according to The Guardian. His portrait of the physician, with its dark blue swirling background, invites the viewer to focus on the subject's face. Vincent van Gogh described this face as "weary with the heart-broken expression of our time."

Apart from his melancholy appearance, the composition also contains another telling detail. On the table in front of Gachet, van Gogh included a small bouquet of foxgloves. Some say Gachet used compounds found in foxglove, known corporately as digitalis, to treat his patient's seizures, which raises some fascinating questions (via The Guardian).

Like many other substances used in medicine today, digitalis is both a medicine and a poison. Dosage is everything. In large doses, the plant proves toxic. It also produces a variety of symptoms, including high concentrations of digoxin in the retinas. These concentrations give everything a yellow hue, which may explain van Gogh's obsession with yellow later in life and other artistic choices. Of course, this interpretation also adds a dark tension to the portrait of the good doctor, poison in hand.

The Bedroom, 1888

While living in Arles, France, Vincent van Gogh occupied a property known as the Yellow House, as reported by the Van Gogh Museum. The artist went on to make two other paintings of the bedroom, depicting the room with a few of van Gogh's interior decorating touches, including rustic furniture and his own paintings on the wall. These paintings changed with each new attempt at depicting his bedroom, per Art in Context.

In his version of "The Bedroom" from 1888, van Gogh's love of the Japanese esthetic shines through again. This is visible in the flattened perspective of the room and the absence of shaow. Two paintings are visible on the wall, according to the Art Institute of Chicago.

Easily overlooked, these pictures on the wall are two of his own masterpieces, portraits of Eugène Boch and Paul-Eugène Milliet, titled respectively "The Poet" and "The Lover." Boch was a fellow painter whom van Gogh admired for his unique vision. As for Milliet, van Gogh saw in him the complete opposite of Boch — a French soldier with a big personality.

These incredible details provide insight into van Gogh's world, the paintings he most appreciated, and even what daily life looked like to him as he woke up in the morning.

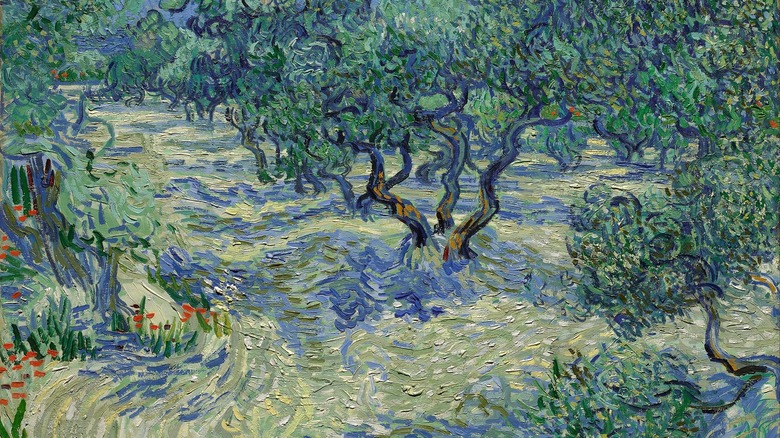

The Olive Trees, 1889

Sometimes the most fascinating details uncovered in Vincent van Gogh's artwork are entirely unintended as with the two fingerprints in the "Fourteen Sunflowers in a Vase" painting (via the Van Gogh Museum). Some more unlikely additions to his canvases have been uncovered in his painting "The Olive Trees."

While seeking rehabilitation at the asylum at Saint-Rémy, van Gogh discovered an ancient olive tree grove behind the Les Alpilles hills that he decided to paint, as reported by The Art Newspaper. Van Gogh fell in love with the trees' gloriously gnarled and ancient looking trunks and glistening leaves. He had to immortalize them in oil paint.

That said, oil paint is a notoriously slow drying and apparently sticky medium as one diminutive insect found out the hard way, according to National Public Radio (NPR). While examining this masterpiece under a microscope, researchers uncovered part of the body of a tiny grasshopper in the mounds of paint piled on the canvas. They also found an unidentified mound of plant material. These correspond with his writings where he mentioned large numbers of insects "flying in the heat" (as quoted in The Art Newspaper). They also relate to the climate of the Rhone Valley, where strong gusts of wind prove commonplace.