The Messed Up Truth About The 2000s Music Industry

The beginning of the new millennium was a time of hip new technology and fear surrounding our growing reliance on it. The decade opened with the Y2K scare, which, per Britannica, was projected to create software chaos as binary-dating computers switched from '99 to '00. Following a year of panicked preparations, humanity and its computers entered the aughts fairly seamlessly. But the music industry didn't.

As the computer age continued, high-speed internet became an affordable option for most households (per USwitch). This created greater global connectivity: Social media sites like MySpace and Facebook flourished, YouTube was born, and peer-to-peer filesharing became commonplace. As USA Today notes, home-recording technology also expanded, allowing artists to create music without the giant upfront costs of renting commercial studios. Artists quickly realized that they didn't need a record label -– or an expensive CD release –- to succeed.

The music industry simply wasn't equipped to deal with the rapid changes of the modern age. As the major labels' booming oligopoly slipped away, record companies resorted to desperate measures to save themselves and things got ugly fast. Here is the messed up truth about the 2000s music industry.

Napster opened Pandora's Box

All it took to bring the music industry down was a computer program. According to The BBC, it started when 19-year-old computer hacker Shawn Fanning developed software that allowed him to easily trade electronic music files with his friends via the Internet. Launched in 1999, this software -– deemed Napster –- instantly created a global network of free music distribution. What happened next was a perfect storm.

As Steve Knopper notes in his book, "Appetite for Self-Destruction," record companies had been pushing CDs since the format's launch in 1982. In the '90s, this venture paid off in spades –- according to Forbes, CD sales peaked at $13 billion in 1999, comprising almost 90% of the music industry's revenue. Per Knopper, the CD has always been a money-making machine, since they historically have been sold at a large profit margin. As the '90s wore on, this margin consistently increased -– by 2000, a CD could cost up to $18, according to Pitchfork.

Frustrated with these outrageous CD prices, people jumped at the chance to download free music. According to Elliot Obermaier in "Perspectives on the Black Market," Napster had over 75 million users by the end of 2000. People also enjoyed the ability to download music directly, explore new genres without risk, and collect individual songs rather than entire albums. Unfortunately, artists and record companies saw no profit from these downloads, meaning the price of an album had gone from its highest point in history to free in under a year.

The music industry's war on piracy became a PR nightmare

The music industry has another word for unregulated filesharing: piracy. As Kerrang! notes, Napster wasn't the first pirate attack –- that famously happened in the early '80s with home taping. But unlike the laborious act of illegally copying and distributing bootlegs, filesharing could be done in minutes (or hours, depending on connection speed). The Internet proved to be a much more formidable foe.

The Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) sued Napster for copyright infringement in 2000, but the legal proceedings flew beneath the public's radar until Napster angered a particularly well-known band. After Metallica's single "I Disappear" mysteriously leaked far ahead of its planned release, the heavy metal rockers were quick to act, suing Napster on April 13, 2000. As Metallica drummer Lars Ulrich told The Huffington Post, "They f****d with us, we'll f*** with them."

Unfortunately, "them" later extended to include everyone who used Napster, which happened to be music lovers. Metallica ended up winning their suit against Napster (per Kerrang!) and, according to History, so did the RIAA. By 2001, the platform was all but defeated –- but the damage had been done. Metallica came to symbolize the greed of the music industry, and, according to The Wall Street Journal (via The Hollywood Reporter), the RIAA went on to sue around 35,000 individuals, including a child and a dead person. It was not a good look.

CD sales plummeted as music went fully digital

Although its glory days were short-lived, Napster had given the world a taste of digital music. According to Elliot Obermaier in "Perspectives on the Black Market," other peer-to-peer filesharing programs like LimeWire and Kazaa quickly took its place. Record sales, meanwhile, fell by 33% in 2000 alone. The message was clear: MP3s were the future of music.

Still, the music industry clung to CDs. According to The Guardian, it had focused more energy on combating CD burners than investing in digital music in the late '90s. Then, instead of pivoting, it wasted valuable years fighting Napster (per The BBC). Steve Jobs, meanwhile, saw opportunity. As History notes, his company, Apple –- then a struggling computer manufacturer (per The New York Times) –- launched iTunes in 2001. This computer program allowed CDs to be converted to MP3s and burned, taking music one step closer to going fully digital. Later that year, the iPod –- a sleek portable MP3 player -– was released, making it possible to carry thousands of songs in a pocket.

According to Wired, Jobs then convinced the major record labels to sign off on a digital music store. In 2003, the iTunes Store was born, allowing songs to be purchased and immediately downloaded, bypassing a physical format altogether. The CD's fate was sealed. As CNN Money notes, an industry that once peaked at a revenue of $14.6 billion in 1999 was reduced to a mere $6.3 billion by 2009 –- a situation that could have been mitigated had digital music been embraced earlier.

Janet Jackson took all the blame for a wardrobe malfunction

Few who watched it will ever forget 2004's Super Bowl 38 halftime show, which has since come to be known as Nipplegate. As Billboard notes, near the end of Janet Jackson's headlining set, rising star Justin Timberlake made a surprise cameo, and the two performed his hit song, "Rock Your Body." Per People, as he sang the line, "Bet I'll have you naked by the end of this song," he ripped a piece of Jackson's top away, revealing her right breast -– clad only in a star-shaped nipple shield –- on national television.

While only visible for 9/16ths of a second (per Billboard), the exposure -– termed a "wardrobe malfunction" by Jackson's spokesperson -– quickly became one of the biggest scandals of the decade. According to People, MTV, Timberlake, and Jackson all issued formal apologies for the incident, which they maintained was an accident, and the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) investigated the performance for indecency violations.

Timberlake won two Grammys that year, continued to enjoy a prosperous career, and even performed at the Super Bowl again in 2018. Jackson, meanwhile, was punished severely. According to Billboard, she was banned from attending the 2004 Grammy Awards, lost a movie deal, and was ruthlessly mocked online. Her songs and music videos were also blacklisted, causing her album "Damita Jo" to flop. According to the documentary "Malfunction" (via NPR), the unfair focus on Jackson was likely due to a combination of racism and misogyny in the entertainment industry.

A payola scandal resulted in radio stations playing fewer new songs

After a career spent exposing corruption in the financial, drug, and insurance worlds, New York attorney general Eliot Spitzer set his sights on the music industry. According to The Guardian, he spent a year investigating how record companies did business in the early 2000s. The results were appalling, if not entirely shocking.

Spitzer compiled 59 pages of damning correspondence between major label Sony BMG and radio programmers in which Sony offered money, vacations, assistance with expenses, and concert tickets to ensure that their artists' songs got airplay. In one particularly shameless email exchange, a Sony employee told a programmer, "What do I have to do to get Audioslave on WKSS this week? Whatever you can dream up, I can make it happen."

The practice of radio pay-for-play, known as payola, is nothing new in the music industry. In fact, it created such a fiasco in the 1950s that it was made a federal offense. But this hasn't deterred record companies from finding sneakier ways of accomplishing it. Following Spitzer's allegations, Sony apologized and paid a settlement of $10 million in 2005. As Steve Knopper notes in his book "Appetite for Self-Destruction," radio stations became warier of record company submissions following the scandal, and station higher-ups started tracking CDs received from labels. Out of caution, many programmers opted to recycle older songs instead, meaning fewer new songs got played.

Lip-syncing was unforgivable

According to Something Else!, lip-syncing has been a part of the music industry since the 1940s. The practice continued through the '80s, as people expected live shows to match the glittering perfection of the staged music videos they saw on MTV. Performances became increasingly extravagant, and artists like Madonna and Michael Jackson began lip-syncing simply so they would sound good while executing strenuous dance moves and other acrobatics. For the most part, audiences could care less. This all changed in 1989 when R&B duo Milli Vanilli was caught lip-syncing, and it was later revealed that the pair were not the singers listeners heard on the recordings –- or even singers at all.

Fans felt betrayed by this lack of authenticity, and from that moment on were quick to point out when an artist used a backing track. One of the most famous examples of this newfound scorn was the demise of pop singer Ashlee Simpson's brief musical career following a lip-syncing mishap on Saturday Night Live in 2004. As Far Out Magazine notes, Simpson's song "Pieces of Me" –- which she had already performed -– erroneously began playing while she was supposed to be singing a second song. Clearly confused and with the microphone nowhere near her mouth as her voice rang out, Simpson performed a few awkward dance moves before skittering off stage. As Something Else! notes, Britney Spears also faced backlash for lip-syncing on her 2009 Australia tour. Some disappointed fans even stormed out of her shows.

Hundreds of record stores went bankrupt

As demand for physical music fell, stores that exclusively sold records began to suffer major profit losses. According to Steve Knopper in his book, "Appetite for Self-Destruction," the demise of record stores was accelerated by the fact that record companies had also started selling CDs in department stores like Target, Best Buy, and Walmart. These stores discounted CDs to free up shelf space for their many other products, and, unable to compete with their competitors' lower prices, hundreds of record stores were forced to close their doors. Even Sam Goody, the ubiquitous mall music store, perished in 2006.

Perhaps the most painful loss was the death of Tower Records, which had been a staple of music culture throughout the '80s and '90s. As NPR notes, Tower Records stores functioned as local hangouts for music lovers and were often staffed with tastemakers and aficionados eager to discuss and recommend albums. According to the documentary "All Things Must Pass" (via NPR), even Elton John made a weekly trip to the store to stock up on new releases. Unfortunately, the chain had gone into debt in an attempt to expand during the CD boom of the '90s, and, with the sudden decline of record sales, was no longer able to break even. Once an international franchise, Tower Records filed for bankruptcy in 2006, taking its unique culture with it.

The industry turned a blind eye to R. Kelly

R&B artist R. Kelly was at the center of several scandals involving underage girls in the '90s. As The Washington Post notes, the adult Kelly illegally married 15-year-old Aaliyah in 1994 (his tour manager secured the fake ID to make it happen), and Tiffany Hawkins accused him of sleeping with her when she was 15, suing his record label in 1996. Still, Kelly's star was shining bright in the early 2000s –- per Celebrity Net Worth, he had probably amassed a fortune of $100 million.

In fact, he was performing at the 2002 Winter Olympics when news that police had obtained his secret sex tape broke. According to reporter Jim DeRogatis in an interview with NPR, the tape –- which featured Kelly having sex with and urinating on a teen girl -– was the worst thing he had ever seen. Kelly stood trial for child pornography charges in 2008 but was acquitted, although his own lawyer later told The Chicago Sun-Times that he was guilty.

His career continued unimpeded until 2017, when Buzzfeed ran a report alleging he kept women captive in a sex cult that renewed public interest in his transgressions. By 2018, several victims had come forward, and a boycott of Kelly resulted in the removal of his catalog from streaming services, as per the BBC. And yet, as The Washington Post notes, his record label, RCA, continued to support him. Per Billboard, RCA did not part ways with Kelly until 2019. As of 2022, he is serving 30 years in prison for racketeering and sex trafficking charges and, per The New York Times, is on trial for sexual abuse.

If you or anyone you know has been a victim of sexual assault, help is available. Visit the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network website or contact RAINN's National Helpline at 1-800-656-HOPE (4673).

The controversial 360-degree deal became the norm

As music sales declined, record companies looked for other ways to keep their profits up. According to Steve Knopper in his book, "Appetite for Self-Destruction," major labels began exploring an arrangement called the 360-degree deal, which allowed them to share in revenue artists earned from merchandise, publishing, touring, and other assets. Where historically labels only earned money from record sales, 360 deals allowed them to profit off everything an artist did in exchange for exposure. Per Vice, such deals became increasingly common in the mid-2000s and represented a shift in the music industry: Artists were no longer viewed as music makers but as celebrities whose entire careers had to be managed.

In an interview with Hit Quarters, Panos Panay, the CEO of online promotion company Sonicbids, cited a core issue with the 360 deal: "They're going to tell you, 'You have to put out another record, you have to go on the road ...' There's two things we know about creativity: you can't force it and you can't really control it." And, in an interview with Billboard, indie musician Mac DeMarco advised artists to avoid signing a 360 deal at all costs, claiming it was outright theft and warning that it gave labels complete ownership of an artist's image -– yet, as he said, "They're not on the stage."

Live Nation made concerts more expensive

As the music industry's empire crumbled, other corporations were quick to capitalize on the future of music profits: concerts. The most successful of these was Live Nation, which, per The Wall Street Journal, was born in 2005 as a rebranding of Clear Channel Communications' entertainment unit. In 2006, Live Nation acquired most of the large music venues in the United States when it purchased the House of Blues chain (per The Wall Street Journal). According to Rolling Stone, the company also signed a multi-million-dollar 360 deal with Madonna in 2007, marking the first of many such arrangements with top-tier artists.

Live Nation quickly became the largest concert promotion company in the world. According to Tech Crunch, they secured an even greater hold over the industry in 2009 when they initiated a merger with Ticketmaster, the world's biggest ticket seller. As The Guardian notes, this gave one entity –- later named Live Nation Entertainment –- dominion over more than 140 venues, 200 artists, 22,000 shows, and 150 million tickets a year.

Many people feared that such a monopoly would negatively impact fans –- and indeed it has. Per Time Magazine, Live Nation Entertainment's add-on fees can reach up to 78% of the ticket price -– which is already three times what it was in the mid-'90s -– in 2022. Many tickets are also intentionally held back or purchased by resellers, which increases demand and drives resale costs up 50% to 7,000%. With no other ticket sellers to turn to, fans are now forced to choose between paying the astronomical prices or missing shows.

Chris Brown violently assaulted Rihanna

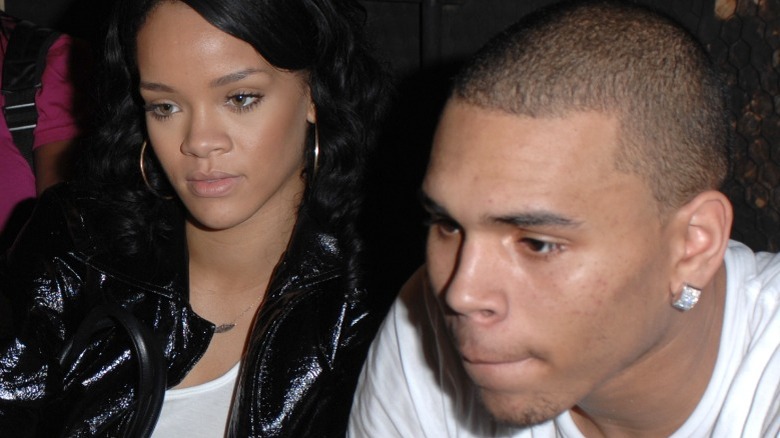

R&B artists Rihanna and Chris Brown were music's hottest couple in the late 2000s. According to E News, then 20-year-old Rihanna was fresh off her success with 2007's "Umbrella," and then 19-year-old Brown's 2005 debut album had already sold over three million copies when the pair got together. Both were scheduled to perform at the 2009 Grammys, but, unfortunately, tragedy struck the night before the event.

According to the Los Angeles Police Department, the two were traveling in a car together when Rihanna discovered a text message from Brown's ex-girlfriend on his phone, which led to a fight. While driving, Brown slammed Rihanna's head against the window, repeatedly punched her in the face, bit her ear, and threatened to kill her. Once parked, he nearly suffocated her via a headlock and beat her before she managed to call for help.

As NBC News notes, Brown was charged with felony domestic assault but was given a lenient punishment of community service, counseling, and a restraining order, managing to avoid jail time completely. His label didn't drop him, and his career barely suffered. In fact, he even won a Grammy in 2012 (per CBS News). Per NBC News, his violence against women hasn't stopped, either: an ex-girlfriend filed a restraining order against him in 2017, and he was accused of punching a woman in 2021.

If you or someone you know is dealing with domestic abuse, you can call the National Domestic Violence Hotline at 1−800−799−7233. You can also find more information, resources, and support at their website.