Colonel Sanders' Crazy Real-Life Story

Colonel Sanders is an American advertising icon whose goateed and bespectacled face is as well known around the world as Ronald McDonald or the Kool-Aid Man. The difference, of course, is that Colonel Sanders was an actual person, and he also never had to touch a Grimace. It can be easy to forget that he was a real man and not just a cartoon character when you see Rob Lowe in a wig and space suit mugging to the camera and telling you he's the Colonel, and you should buy his limited-time-only Space Chicken or whatever nonsense KFC is selling now.

He wasn't just a real person but almost a model of the American dream, starting from nothing and working his way up to great success just through grit, determination, hard work, and serving deep-fried foods to Americans. His life story is a buckwild roller coaster, full of struggles and gunfights and not finding success until Social Security times. And also Duncan Hines was there.

Give this a read, and next time you're cuddled up to a bucket of extra tasty crispy, think about the kind of life you would have to lead so your FBI profile would read "Colonel Harland F. Sanders has not been the subject of an FBI investigation" followed by two full paragraphs of redacted text. That's wilder than a Famous Bowl full of Double Downs.

His early life was basically a Mark Twain novel

As laid out in this profile from the New Yorker in 1970, Harland Sanders had a hard go of it from a young age following his birth outside Henryville, Ind., in 1890. He was raised by an ultra-religious mother who taught him that alcohol, tobacco, coffee, and playing cards were all equally poisonous. After his mother got married to a man who wasn't so keen on the idea of stepchildren, Sanders had to go make his way in the world — at 12 years old. He worked on a farm while going to school, and when that got too hard, he quit school just two weeks into seventh grade. Over the next three decades of his life, he was a streetcar conductor, a railroad fireman, studied law by mail, worked as a midwife, operated a steamboat ferry, and even more, mostly failing at all these things.

If the next thing you read was that he and a former slave stole a raft and tried to escape the civilizing influences of Aunt Polly, you'd probably nod and say, "Sure, sounds right." But the truth is maybe even wilder. In the middle of all that other stuff, he got married at age 18 and had three children. As Snopes summarizes from Sanders' autobiography, after Sanders got fired from the railroad, his wife left and went to her parents in Alabama. Sanders planned — and failed — to kidnap his own children, and instead he just reluctantly reconciled with his wife. (They divorced almost 40 years later.)

He eliminated his culinary competition in a shoot-out (but not the way you think)

Harland Sanders' life would change at age 40 when he began selling food to travelers from the back room of the gas station he ran in Corbin, Ky. As History points out, he became a hit with travelers selling his simple country fare of country ham, okra, biscuits, string beans, and similar items as an alternative to the typical diner food found along the highways. Ironically, for some time the one thing he didn't serve was fried chicken. It took too long to prepare to be able to keep up with demand.

Sanders would advertise the food at his Shell station by painting giant signs on barns in the area. This clever marketing scheme greatly upset Matt Stewart, the operator of a nearby competing Standard Oil station. Stewart began painting over Sanders' signs, so Sanders went to pay him a visit along with two Shell district managers. What they weren't expecting was that Stewart had a gun, with which he shot and killed one of the managers. Sanders, who was a known tough guy famous for "the force and variety of his swearing," naturally had his own gun and returned fire. He only wounded Stewart in the shoulder, but even if he didn't knock out his competition by killing him, he still got the result he wanted — Stewart went to prison for murder, and charges against Sanders were dropped, leaving him the gas station king of Kentucky.

His chicken was so good, he got named a colonel (but not that kind of colonel)

If you know one thing about Colonel Sanders, it's probably that he made chicken. But if you know a second thing, well, it's that he's a colonel. Heck, you might even think "Colonel" is his first name. Certainly more people could name "Colonel Sanders" than "Harland Sanders."

But while it's true that Harland Sanders did serve in the Army, he wasn't that kind of colonel. As History relates, he lied about his age to join the Army in 1906 at age 15 or 16. He served in Cuba but only for about six months before he was honorably discharged. While Sanders' autobiography does not mention why, chances are good it was because they figured out he was 16.

Suffice it to say, this was not enough time for him to ascend to the rank of colonel, which is pretty high up there. So was he lying about being a colonel? Is that a thing you can go to jail for? (Apparently no, unless you wear medals or uniforms you didn't earn.) But, no, he wasn't lying about being a colonel. He was, indeed, a Kentucky Colonel, which is the highest honorary title bestowed by the governor of Kentucky. (Lots of famous people get named Kentucky Colonels. Muhammad Ali was one. Bob Barker was one for some reason.) Sanders was declared a colonel by Governor Ruby Laffoon in 1935 and then got re-upped in 1949 because his chicken was just that good.

He got famous because of Duncan Hines

Colonel Sanders didn't often make chicken in his restaurant at first, because, as the New Yorker explains, pan frying chicken took too long — up to 30 minutes after a customer had ordered it. Deep frying chicken produced dry, unevenly cooked meat. Then in 1939, he had probably the most important breakthrough in chicken history. He began frying his chicken in a pressure cooker, which gave him the right balance of time and quality. Combine that with the fact that at this time he was refining his famous blend of 11 herbs and spices, and Sanders was ready for explosive success.

And just in time, too. In 1935, Sanders' cafe (which he opened after his success with food completely eclipsed his need to run a gas station) had been named as a must-see destination while on the road in Duncan Hines' travel guide, "Adventures in Good Eating." (Side note: Duncan Hines was a real person and not just a name on a cake mix box. He wrote reviews of cool places to eat on the road. Betty Crocker is totally fake, though.)

Sanders was now nationally famous and had expanded his back-room-in-a-gas-station kitchen into a 142-seat restaurant. It seemed like, finally, at age 49, after a host of weird jobs and shoot-outs, Sanders had finally found success. As it turns out, he hadn't seen anything yet. But first he had to deal with some bad news, because, you know, life.

The first Kentucky Fried Chicken was in Utah, not Kentucky

In the early 1950s, Colonel Sanders suffered a couple of blows to his success. As explained by the New Yorker, the highway junction that ran in front of his cafe was moved to another site, and then a new interstate highway was built that took traffic away from his location entirely. After a decade of success, it looked like Sanders was done for. In 1956, he auctioned off his business at a huge loss and was now, at age 65, living entirely on his savings and a Social Security check of $105 a month.

Fortunately, he had planted the seeds to save himself back in 1952 — the seeds of franchising. According to History, Sanders taught his chicken-frying methods and recipe to his friend Pete Harman in Salt Lake City. As it happens, Harman owned one of the largest restaurants in the city, and he started selling Sanders' chicken as his first-ever franchisee, advertising it under the banner of "Kentucky Fried Chicken" and selling it in the soon-to-be trademark bucket.

Now in his 60s, Sanders found himself in the franchise business. Following Harman's success, other businesses wanted to sell Sanders' chicken and made arrangements to give him 4 cents for every chicken cooked via his process. Sanders hopped in his 1946 Ford and drove around the country, sleeping in his car with pressure cookers and a bag of spices, looking far and wide for franchisees and finding them everywhere. By 1963, Sanders had over 600 restaurants in the United States and Canada selling his chicken.

He became a brand ambassador at age 73

Pete Harman would be an extremely important contributor to Colonel Sanders' increasing success. According to Smithsonian Magazine, in addition to coming up with the name "Kentucky Fried Chicken" and being Sanders' first franchisee, he also came up with the bucket, the phrase "finger-lickin' good," and the idea of standalone KFC restaurants rather than just Sanders' chicken being an item on other restaurants' menus. Harman alone would own more than 300 KFC franchises in Utah, California, Nevada, and Washington. But despite being basically the co-founder of the franchise, it's not his face on the bucket. That's okay, though. The Colonel made him a millionaire.

The Colonel himself became a millionaire in 1964 at the age of 73, when he sold Kentucky Fried Chicken to a group of investors for $2 million. The New Yorker says he was reluctant at first, but the investors persuaded him by saying they would never tamper with his recipe and that he could stay with the company as an adviser and brand ambassador, the living face of the company. The new owners felt having a living, authentic company symbol was a great asset, especially compared to fictional figures like Aunt Jemima or Betty Crocker (who you will remember is totally fake). Soon the Colonel was making appearances on The Tonight Show and Merv Griffin, as well as a just truly ridiculous number of television commercials and other advertisements, with KFC spending $24 million on advertising in 1970, compared to half a million in 1964.

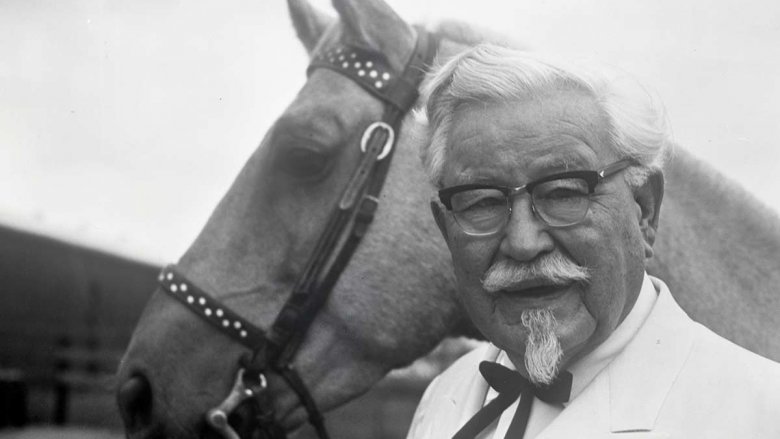

He wore only his trademark white suit for the last 20 years of his life

A big part of the Colonel's success as an advertising icon was his trademark look. As History explains, after his second commission as a Kentucky Colonel in 1949, he decided to really lean into the whole "Southern gentleman" thing and just really went whole hog. He grew out his facial hair and started wearing a string tie. At first he wore a black frock coat but soon switched to his iconic all-white suit after realizing it hid flour stains much better. Additionally, he started bleaching his mustache and goatee so they'd match his naturally white hair.

And he really leaned into it. As Colonel Sanders biographer Josh Ozersky wrote for Time, Sanders actually called himself "Colonel" and had others do the same. He wore his white suit every day and, indeed, it was the only thing he wore in public for the last 20 years of his life, and not just for advertisements or TV appearances, like the delightful one from What's My Line in 1963 above. He had a light cotton version he wore in summer and a heavy wool version he wore in the winter.

The suit has become so iconic that suits actually owned and worn by the Colonel can sell at auction for up to $80,000. Furthermore, the suit and facial hair are enough to make actors as diverse as Darrell Hammond, Norm MacDonald, Jim Gaffigan, George Hamilton, Rob Riggle, and Billy Zane recognizable as the Colonel.

He came to hate KFC food and talked trash about it at every chance

Although Colonel Sanders remained the symbol of the company and traveled 200,000 miles a year making appearances on television and at the company's franchises, Sanders came to hate the changes the company made after he was no longer in charge. The New Yorker reported Sanders dreamed of gravy so good "it'll make you throw away the durn chicken and just eat the gravy." However, the gravy made by post-Sanders franchisees was decidedly not the Colonel's gravy. A company executive was quoted as saying, "Let's face it, the Colonel's gravy was fantastic, but you had to be a Rhodes Scholar to cook it," which was probably code for "too expensive."

The Colonel didn't care for such changes to his recipes and wasn't shy about letting people know it, despite his job as brand ambassador. He would visit franchises, and if the gravy wasn't up to his standards, he would throw the food on the floor and call it "god-damned slop." Worse, in an interview in the Louisville Courier-Journal, he referred to the gravy as "pure wallpaper paste" made with tap water, flour, and starch to which they add "some sludge" and said that the then-new crispy recipe was "nothing in the world but a damn fried doughball stuck on some chicken." His criticism of KFC was so harsh that the company he founded sued him for libel in 1978. The case was thrown out, but don't worry — it happened again.

He got sued by KFC and lost

Suffice it to say that Colonel Sanders was not happy with the changes made to his chicken and gravy recipes in the name of saving money and streamlining for thousands of franchises. Can you imagine the glorious explosion of rage that would cover this land if the Colonel were to appear in a chicken grease-fueled DeLorean from the year 1978 and see a Go Cup or a Double Down? Just the world drowned in a deluge of swears and not a single skull un-cracked by the Colonel's cane.

In the 1970s, however, when Sanders was now in his 80s, his solution was somewhat different. He and his once-mistress-now-wife Claudia opened a new competing restaurant that served food that rose to the Colonel's standards. As reported in People magazine, the restaurant, known as Claudia Sanders, The Colonel's Lady Dinner House, would sell sit-down-style dinners of ham and lobster in addition to chicken. They attempted to expand this business into a chain as well, but KFC wasn't thrilled about that and sued them to the tune of $120 million. According to Uproxx, the suit was settled for $1 million and Sanders sold the restaurant. The Claudia Sanders Dinner House still exists, though, and you can visit it, right off I-64 east of Louisville. It is the only non-KFC restaurant that sells a fully authorized version of the original Colonel Sanders fried chicken recipe. Plus lasagna if you want. Can't get that at KFC.

His ghost has cursed a Japanese baseball team

Sanders died in 1980 at age 90 of acute leukemia. He had kept working until a month before his death. Flags were flown at half-staff for his funeral, which was attended by over 1,000 people. That seems like it should be the end of his story, outside debates over the propriety of his image being used in continued advertising after his death, but for some Japanese baseball fans, the Colonel's death was only the beginning.

Here's the short version of the story, as reported by NBC News. Osaka's baseball team, the Hanshin Tigers, won the national championship in 1985. Tigers fans often jump in Osaka's Dotonburi River to celebrate wins. After the championship, some rowdy fans decided that a statue of Colonel Sanders outside a local KFC looked enough like the Tigers' American first baseman Randy Bass that he should go in the river too. So ... they threw the statue in the river. Since that time, fans feel the team has been plagued by "the curse of the Colonel," which is to say, the Tigers have not won another championship.

The statue was recovered from the river in 2009, but it had deteriorated pretty greatly in the interceding years. He was missing his legs, hands, and glasses when pulled from the murky waters of the Dotonburi. The legs and right hand were recovered the next day, but the left hand and glasses are still missing. Tigers fans assert it is because of these still-missing pieces that the curse is still in place.