Women Elected To Office In America Before They Could Vote

Most people know that the 19th Amendment to the Constitution of the United States of America codified the right to vote for women. More accurately, it forbade state governments from denying the vote to people because of their sex. But that doesn't mean women didn't have a political voice prior to 1920 when the amendment passed.

Prior to the 19th Amendment, individual states made their own decisions on women's suffrage, according to Time. In fact, most states allowed women to vote in at least some elections prior to 1920 — only eight of 48 states completely disenfranchised women. Even when they weren't allowed to vote, nothing prohibited women from running for office in many cases — and they often did. Thousands of women ran for office prior to 1920 and many of them won and served long before they were legally allowed to vote. Here are some of the women elected to office in America before they could vote.

Olive Rose: The first woman elected

The Washington Post reports that Olive Rose was the first woman to be elected to political office in the United States when she won the race for Register of Deeds in Lincoln County, Maine in 1853. According to Her Hat Was In the Ring!, Rose didn't just win this election, she crushed it, taking 73 votes to her opponent's four. Since this was close to 70 years before the 19th Amendment, every single ballot Rose received was cast by a man.

While some newspapers celebrated Maine's progressive achievement — like The Lewisburg Chronicle cheering that "Maine has taken the lead in the practical illustration of the Women's Rights doctrine" — others lamented Rose's election. As noted in, "The History of Women's Suffrage," the publication Maine Age reported that it "deprecated" Rose's election and warned that "women will not simply fill your offices of Register of Deeds, they will occupy seats in your Legislative Halls, on your judicial benches, and in the executive chair of State and Nation."

Adeline T. Swift: Elected but disqualified

Prior to the 19th Amendment, the laws governing women's suffrage and their ability to serve in public office were a patchwork of different requirements. But even when someone is legally prevented from running for or holding office, typically nothing stops them from campaigning, and nothing stops people from casting votes for them even if ultimately it comes to nothing.

Such was the case in 1854 when, according to "Women in the American Political System," Adeline T. Swift was elected to the board of supervisors in Penfield, Ohio. Swift was known as an abolitionist and an activist in women's suffrage, so her election would have been a key achievement — if it had been allowed to stand. As historian Elizabeth D. Katz notes, Ohio's state constitution made being an "elector" (i.e., having the right to vote) a requirement to hold public office. Since Swift was a woman and thus not allowed to vote, she was disqualified from taking her seat on the board. As noted by Her Hat Was In the Ring!, Swift knew that just by winning the election she had achieved something. She was quoted as saying the voters had "honored me with your votes" as a "reward of my labors in the cause of Woman's Rights."

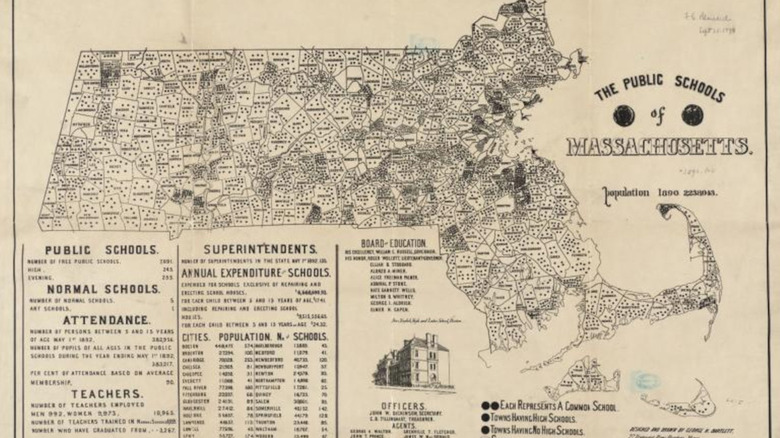

Marietta Patrick and Lydia Hall: School board pioneers

As noted by the ThoughtCo., political careers in the United States have a tendency to start off local and school boards are often a politician's first elected position. This was as true in the 19th century as it is today, so it's not surprising that two of the first women elected to office in this country joined a school board. As reported by the Swarthmore College Bulletin, Lydia Hall and Marietta Patrick became the first women to be elected to a school board when they were elected to the body in Ashfield, Massachusetts in 1855. According to "Women in the American Political System," both women were teachers, making them obviously qualified for the position.

The National School Boards Association notes that while Patrick only served for one year before stepping down in order to get married, Hall served four years as a testament to her effectiveness and popularity in the position.

Julia Addington: The tie-breaker

Julia Addington was born in 1829 and by 1869 she was a respected educator in her home state of Iowa, having served as the preceptress at Cedar Valley Seminary school and worked as a teacher at several schools in the state. At the age of 40, she ran for the post of Superintendent of Schools in Mitchell County, Iowa. According to author Cheryl Mullenbach, the election ended in a tie, with Addington and her opponent Milton Browne each receiving 633 votes. The winner was ultimately determined by a "cast of lots," meaning the final decision was left to chance. Even after being declared the winner, Addington faced strong opposition. The Iowa Attorney General eventually had to settle the controversy by ruling that there was actually no legal reason why Addington couldn't serve in the post.

Addington served for two years and was asked to serve a second term but chose to retire in 1871 due to poor health. She passed away just four years later. But in her two years as superintendent, Addington was in charge of 76 schools and more than 2,000 students. In 2010, Addington was inducted into the Iowa Women's Hall of Fame.

Amanda T. Million: First in Kentucky

"A Simple Justice: Kentucky Women Fight for the Vote" notes that Amanda T. Million was "something of an accidental hero" in the cause of gender political equality. Her husband, Jackson Million, was the serving superintendent of schools for the state. After running unopposed for a second term in 1886, he was re-elected but promptly died of typhoid fever. As noted by Laura Clay in, "History of Woman Suffrage," Judge J.C. Chenault appointed Amanda to finish out her husband's term after determining that there was no legal reason she couldn't serve in the post.

In 1887, Million became the first woman elected to a political office in Kentucky, according to Her Hat Was in The Ring! She knew the importance of her achievement, noting in one official report that Kentucky had lacked the "courage" to elect a woman before. Million served out the next three years of the term and successfully ran for re-election several times, serving as superintendent until 1901 when J.W. Wagers took over the post. She passed away in 1919 but is remembered today as a trailblazer in Kentucky politics.

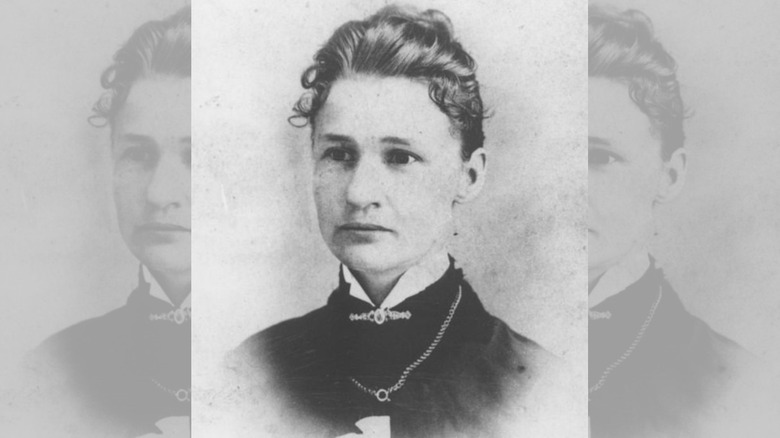

Susanna Salter: America's first mayor

According to Her Hat Was In the Ring!, Susanna Salter never wanted a career in politics, didn't want to be mayor of Argonia, Kansas, and wasn't even aware that she'd been nominated for the post.

As noted by the Kansas Historical Society, women had just gained the right to vote in city elections in Kansas in 1887. Salter was a well-known temperance activist who worked towards the prohibition of alcoholic beverages. When the Women's Christian Temperance Union put forth a slate of local candidates touting the benefits of prohibition, a group of booze-loving men (who were known as the "Wets") secretly put Salter's name on the ballot, believing that the absurdity of having a young mother as mayor would drive people to vote against the temperance candidates (via The Washington Post).

As noted by The Foundation for Economic Education, their plan backfired. The local Republican party went to Salter's house and asked if she would seriously serve as mayor if elected, and she replied that she would. The local Republicans decided to endorse her candidacy, and she won the election with two-thirds of the vote. According to Smithsonian Magazine, that made her the first-ever woman to serve as mayor in the country. During her single one-year term, one of her first orders was to ban hard cider within city limits.

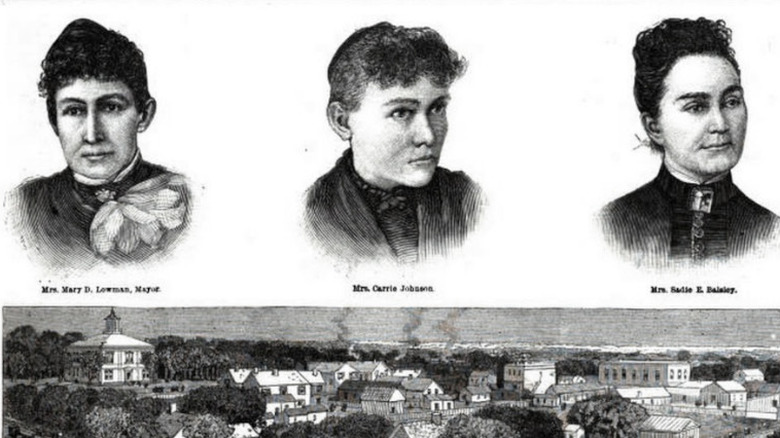

Mary D. Lowman: The first all-woman government

By the time Mary D. Lowman was elected mayor of Oskaloosa, Kansas in 1888, female mayors were still a novelty but were no longer unheard of. As noted by Her Hat Was In the Ring!, what made Lowman's term as mayor notable was the all-female city council she swept into office on her ticket. Overnight, Oskaloosa became the first town in the United States known to have an all-woman government.

Lowman and her team (Hannah Morse, Emma Hamilton, Sadie Balsley, Mittie Golden, and Carrie Johnson) were inspired to run for office because of the failures of previous administrations. The town's treasury was empty and had a lot of debt, and much of the public infrastructure was in need of improvement. According to "The History of the Women's Suffrage: The Flame Ignites," Lowman and her council were very successful in turning the town around, and were re-elected by a wide margin for a second term. They could have been re-elected for a third term if they'd wished, but reportedly said they had already accomplished enough. Namely, Lowman's administration improved the town's finances, made numerous public improvements, and began enforcing laws that had been ignored for years. They also installed new sidewalks in the downtown area, improved the public lighting system, and ended their term with a budget surplus.

Laura Eisenhuth: The first woman in statewide office

Throughout the 1880s, women elected to public offices had all won local elections but not statewide races. As noted by Her Hat Was In the Ring!, that all changed when Laura Eisenhuth was elected superintendent of public instruction in North Dakota in 1892.

As noted by Doris Weatherford in her book, "Women in American Politics," Eisenhuth was elected superintendent of schools in Foster County in 1889 and re-elected in 1890. She made no effort to seek the nomination for the statewide position, but the Democratic Party nominated her anyway despite her youth (she was just 34) and the fact that she'd been born in Canada. Although her two-year term was a success in many ways, Eisenhuth may have hurt herself politically by appointing her husband as her deputy superintendent and giving many voters the impression he was actually doing the work. Eisenhuth ran for reelection in 1894 and lost to another woman, Republican Emma Bates. After two more failed attempts to run for public office in 1896 and 1900, she returned to teaching full-time. Eisenhuth died in 1937 and her achievement was largely ignored until many years later.

Clara Cressingham, Carrie C. Holly, and Frances Klock: First state reps

According to author Sue Thomas in the book "Gender and Women's Leadership," the first women to ever be elected to a state legislature were Clara Cressingham, Carrie C. Holly, and Frances Klock, all elected to the Colorado House of Representatives in 1894. Their election came just one year after Colorado granted women the right to vote in the state, with 78% of eligible women voting in the election versus just 56% of men.

According to Her Hat Was In the Ring!, Cressingham represented the city of Denver; Holly represented Vineland, Pueblo County; and Klock represented Araphoe County. Each served one term, and as noted by the Colorado Encyclopedia, Klock also made history by becoming the first woman to chair a legislative committee, leading the Committee on Indian and Military Affairs.

Both Cressingham and Holly were long-time suffragists, but Klock was not known to be an activist for women's voting. She was, however, anti-Catholic and a member of the local chapter of the American Protective Association, which aimed to exclude Catholics from public life. This complicated her legislative achievements, as she actually had to vote against one of her own bills involving a reformatory school.

Dr. Martha Hughes Cannon: The first female state senator

According to the National Women's History Museum, Dr. Martha Hughes Cannon was born in Wales and immigrated with her family to the U.S. in 1860, when she was three years old. A Mormon, she went to medical school, graduated when she was just 23 years old, and went on to earn a pharmacy degree as well. According to PBS, she returned to Utah where she became the fourth of six wives to Angus M. Cannon. Because the government was prosecuting polygamous marriages at the time, Cannon was forced to flee the country for several years.

When the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints finally disavowed polygamy, Cannon was able to return to Utah, where she opened a training school for nurses. In 1896, Utah officially became the 45th state. With its admission, women were granted full suffrage — thanks in part to Cannon's activism, according to historian Rebekah Clark. Cannon was the first woman to officially register to vote in Utah.

Later that year, Cannon — running as a Democrat against her own Republican husband — also became one of the first candidates for state senator in Utah's history. Cannon wasn't just the first female state senator in the U.S., she was also the only woman in the Utah senate. Despite a successful legislative career, Cannon chose not to run for re-election — possibly due to the scandal that erupted when her husband was convicted on polygamy charges and jailed.

Pauline Steinem: The first Jewish woman elected

Pauline Steinem — grandmother of feminist icon Gloria Steinem — was born in Germany and moved to Ohio when she was 19 after marrying Joseph Steinem. The Ohio History Connection notes that Steinem became active in the local Jewish community, then broadened her activism to other women's organizations and emerged as a notable force in the suffragist movement.

As noted by Her Hat Was In the Ring!, Steinem also established herself as an authority on education in Toledo, and in 1904 she was put forward by a coalition of women's activist groups as a candidate for the Toledo school board. Notably, she had the support of the city's mayor, Samuel "Golden Rule" Jones, a progressive politician she had often worked with in her roles as an activist and educator.

Women had been able to vote in Ohio since 1894, but many suffered harassment from men when they tried to cast ballots or run as candidates. Steinem organized women into large groups to go vote together in order to discourage these kinds of intimidation tactics. In the end, Steinem received a record number of votes, most likely becoming the first Jewish woman elected to public office in this country. As noted by her granddaughter in the Jewish Woman's Archive, Steinem was one of the few women listed in the "Who's Who in America."

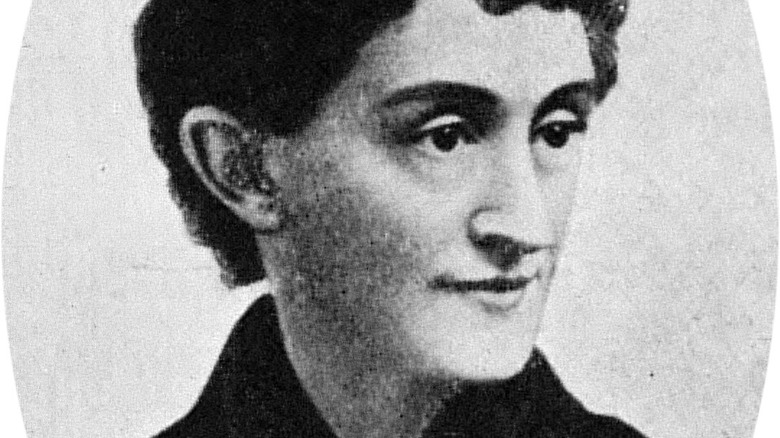

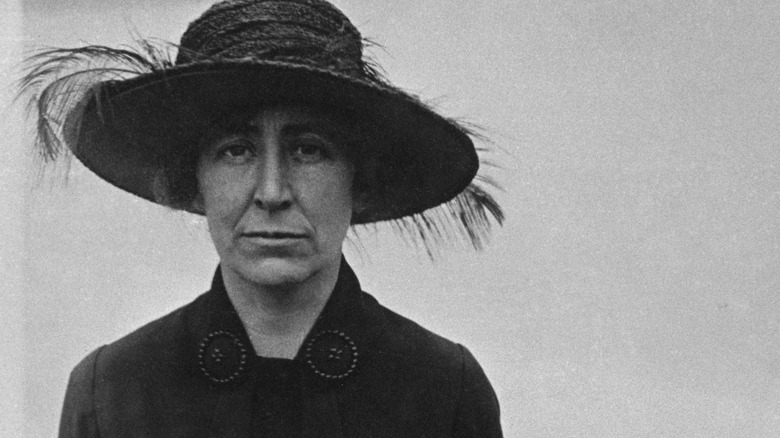

Jeannette Rankin: The first woman in national office

On November 7, 1916, Jeannette Rankin made history: Four years before women gained the nationwide right to vote, she became the first woman elected to Congress, according to Time. Running for one of two of Montana's at-large seats, Rankin benefited from her own activism, as she'd been instrumental in expanding women's suffrage in Montana statewide.

According to Britannica, Rankin was a woman and politician of extraordinary commitment. In 1917, she was one of 49 representatives who voted against declaring war on Germany — and this stand cost her the Republican nomination. Ironically, History notes that Rankin worked to introduce a nationwide women's suffrage bill as well, but it didn't make it past the Senate. The 19th Amendment was finally passed in 1919 after Rankin had left Congress.

But Rankin wasn't done. After years as a lobbyist, Rankin was once again elected to the House in 1940 (she was one of seven women representatives at the time). After the bombing of Pearl Harbor, she once again stuck to her beliefs: She was the sole vote against declaring war. She left office in 1942 as a deeply unpopular politician, and never ran for office again.