The Mystery Of The Cleveland Torso Murderer

Things were starting to look up for Cleveland. After the Great Depression had ravaged much of the country, the city saw improvement in the growing population and the local steel industry. But 1935 saw the beginnings of a series of crimes that would terrorize the city. According to the Cleveland Police Museum, that's the first year that residents of the city realized a killer was stalking the streets. Even worse was his gruesome calling card: Victims turned up in pieces.

Known as the Cleveland Torso Murderer, the killer preyed on the vulnerable people of the city. Over the next three years, a total of 12 bodies would be attributed to the murderer. Police officers and detectives spent thousands of hours on the case, even bringing in famous lawman Eliot Ness. Yet, for all the effort, the murderer was never identified. Decades later, it's still not clear just who was killing people throughout the Midwestern city. This is the mystery of the Cleveland Torso Murderer.

The murders took place in a rough part of Cleveland

In 1930s Cleveland, few places were more downtrodden than Kingsbury Run. This rough and tumble part of town existed in stark contrast to the rest of the city, which was enjoying an economic upturn after years of the Great Depression, per the Cleveland Police Museum. Yet, much as citizens might point to their city's thriving steel industry and booming population of workers, the "hobo jungle" in Kingsbury Run was still there, undeniable and soon to be frightening as the murderer began his work there.

Kingsbury Run was where many homeless people attempted to live among ad hoc housing and piles of trash. Rail lines running through the area allowed transients to move through, making it all the more difficult to know just who lived in the slum. Nearby was another low-rent neighborhood popularly known as the "Roaring Third." According to the Cleveland Police Museum, the area was full of dives, brothels, and places where you could gamble all your money away. With so many people moving through and engaging in discreet business, Kingsbury Run and the Roaring Third proved to be prime territory for a serial killer.

The first two victims were found in 1935

The first signs of a killer appeared in September 1935, when remains were found in Kingsbury Run. But according to the Cleveland Police Museum, the first victim, a man, had been killed elsewhere. The remains were bloodless, while the head and privates had been removed. Officers discovered another male corpse nearby. This man had also been decapitated and emasculated. His skin had been treated with a chemical that made it red and tough. Officials estimated that the second victim was about 40 years old and had been dead for two weeks, but couldn't identify him.

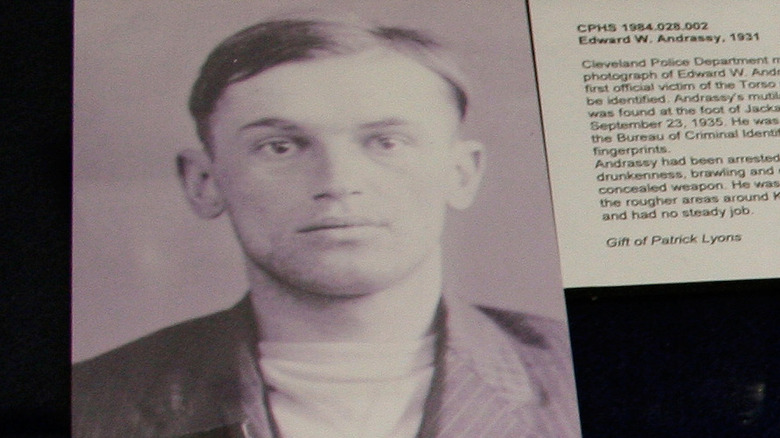

That wasn't the case for the first man, whose head was soon found. Fingerprints identified him as Edward Andrassy. "In the Wake of the Butcher" notes that Andrassy was no stranger to the Cleveland Police Department. A frequent visitor to the Roaring Third, Andrassy was often picked up for drunk and disorderly conduct. One officer recalled that he once had to "knock him down" for his attitude. The purportedly handsome 29-year-old was typically unemployed and was rumored to sometimes sleep off his benders in a cemetery.

Though the state of the remains was undoubtedly gruesome, the most horrific detail might be how the two men died. As noted by the Cleveland Police Museum, detectives determined that both Andrassy and the unidentified man died by decapitation. This meant that they were likely still alive (though probably unconscious) when the killer began removing their heads.

The first victim may have been killed a year earlier

Though Edward Andrassy and the unidentified man were the first to be recognized as the murderer's victims, they may not have been the killer's initial kills. As reported by the Cleveland Police Museum, some think an unidentified woman known as the "Lady of the Lake" could be an earlier victim. In September 1934, the lower torso and thighs of the woman were found beside Lake Erie. Other remnants of her body were found, though not her head. Her skin had apparently been treated with the same kind of preservative later applied to the unidentified man found near Andrassy. For this reason, investigators began to suspect that she died at the hands of the same murderer.

According to "In the Wake of the Butcher," the newspapers that latched onto the lurid case weren't so sure that the Lady of the Lake was a victim. So, too, did police officials and coroners go back and forth on the matter. Things became even more contentious when some linked a series of murders committed before and after the Cleveland killings to the same killer. Murders in New Castle, Pennsylvania that happened before and after the Cleveland killings reportedly fit the profile, as did a dismembered victim found in 1950. Without clear evidence, it's all but impossible to determine just how active the Cleveland Torso Murderer really was throughout the 20th century.

Florence Polillo was found in pieces

The next generally accepted victim of the Cleveland Torso Murderer was found a few months later, on January 26, 1936. According to "True Crime: Ohio," locals found a basket outside a business on East 20th Street. It contained a grisly sight: dismembered parts of a body, wrapped in burlap fabric. Detectives were able to identify the remains from fingerprints taken from a right hand. They belonged to Florence Polillo, a sex worker who lived nearby and was known to associate with others in the sex trade and people in the local bar scene. Eventually, other parts of Polillo were found nearby, though her head was never found.

Though she's traditionally counted as the third victim of the murderer, not all of the details of Polillo's demise matched the killer's modus operandi. According to "American Demon," some investigators thought it was odd that Polillo was the only known female victim. (The Lady of the Lake was yet to be considered by many detectives as a victim.) Likewise, the fact that her remains had been disassembled and left in wrapped packages didn't fit with the pattern established by other remains that had been found.

Many victims remain unidentified

As 1936 wore on, more murder victims were found. In June, two boys discovered the head of a man in Kingsbury Run. A day later, a bloodless and headless corpse of a man was found right in front of a police building, as the Cleveland Police Museum reports. He became known as the "Tattooed Man" for the six tattoos inked on his body, but these did little good to identify him.

In July, another headless corpse of a man was discovered in the wooded area where he'd been killed, though he had died two months earlier. September saw yet another gruesome revelation when the discovery of another male torso found near the train tracks in Kingsbury Run. When police went looking for the rest of the man in a nearby pool, a crowd of nearly 600 people assembled. Adding to the growing frenzy, local newspapers reported every day on the lurid crimes.

Detectives knew that making any connection among victims could be vital and went to unusual lengths to identify them. This included making plaster casts of their faces and putting them on display in the hopes that someone in the crowd of onlookers would recognize them. Though few would be identified, the majority of the Cleveland Torso Murderer's victims were not. Despite the effort on the part of the police force — which sometimes incorporated real hair from the remains — no one stepped forward with names for any of the unidentified.

The murderer preyed on the less-dead

With the majority of crimes taking place in Kingsbury Run, it seemed that many of the victims were probably homeless people or transients moving through the area via railyards. Kingsbury Run was home to a shantytown that had sprung up in the wake of the Great Depression when many became unemployed and experienced serious financial hardship. The collection of makeshift homes grew even larger after Cleveland police cleared out similar settlements along Lake Erie, pushing many to congregate in Kingsbury Run. By the time famed lawman Eliot Ness was brought in to reform the region, it contained hundreds of people (via Cleveland Historical).

Given their poverty and the fact that they had been literally pushed to the edges of the city, the residents of Kingsbury Run were especially vulnerable. Though the term wasn't in use at the time, these individuals would have been amongst the "less-dead." As noted by the "Encyclopedia of Murder and Violent Crime" (via SAGE Reference), this refers to marginalized groups such as sex workers, the homeless, and LGBTQ+ people. The idea is that their lack of connection with higher-ups — paired with a police force that wasn't interested in putting in too much effort to investigate their disappearances — makes them more vulnerable to violent crime. Yet, in the case of the Cleveland Torso Murderer, the killings were so undeniable and gruesome that eventually everyone was forced to pay attention.

Detectives failed to track the killer

As it became clear that a murderer was targeting people in and around Kingsbury Run, the Cleveland Police Department had to take more concerted action. According to "The Encyclopedia of Unsolved Crimes," this meant assigning two detectives full-time to the case. Those were Peter Merylo and Martin Zalewski, who took on a monumental task. Next to nothing was known about the killer, apart from the fact that he had contact with the less-dead of Kingsbury Run and the Roaring Third, and that he may have had some sort of medical training to disassemble remains so precisely.

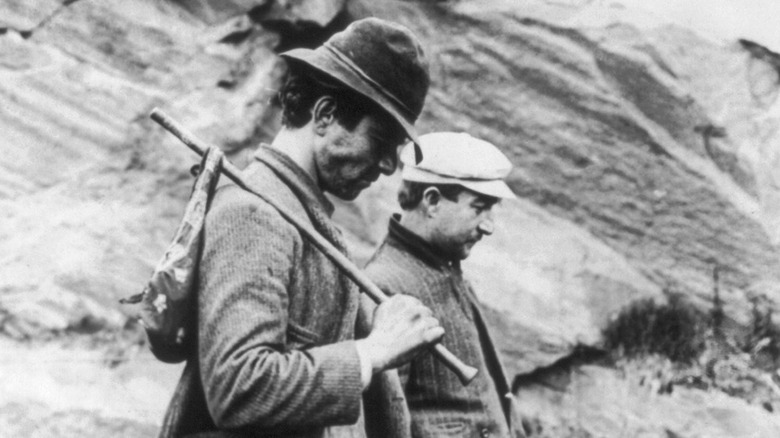

The lack of suspects meant that Merylo and Zalewski had to follow up on an exhausting number of leads, which included interviews with over 1,500 people. The total interviews conducted by the entire police department related to the murderers came out to a staggering number of more than 5,000 (via Cleveland Police Museum). The pair even attempted to go undercover, dressing up as vagrants in order to gain the confidence of potential witnesses and gather evidence. It's also worth noting that detectives often took tipsters to task for other, far more minor misdeeds, making others reluctant to step forward (via The Washington Post). None of this led to the identification of the killer, much less a conviction.

Eliot Ness got involved

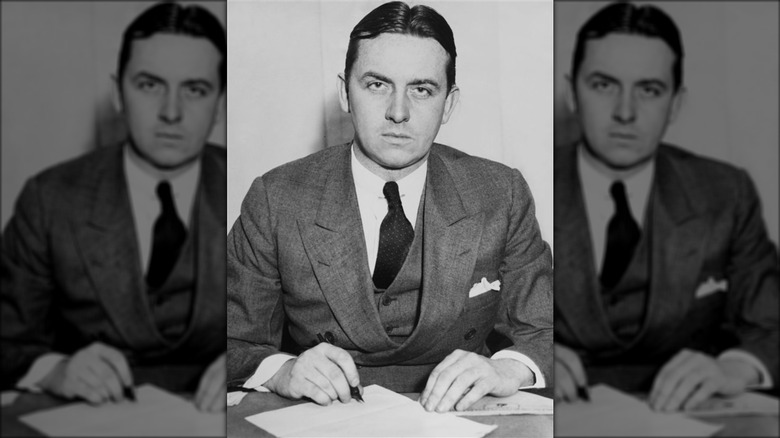

By the time Eliot Ness had become Cleveland's director of public safety, he was already something of a celebrity. As per "American Demon" (via CrimeReads), he had risen to fame as a young lawman in Chicago, helping to bring down the infamous mobster Al Capone as part of the "Untouchables." A couple of years later, Ness landed in Cleveland, making waves with his bold ventures against crime. His efforts often made local newspaper headlines the next day, earning him a spot as a city hero.

Given how dedicated Ness was to land on the right side of the law — and to make sure that the public knew where he stood — the horror of the Cleveland Torso Murderer was all the more galling. There was also the matter of his background. Sure, he brought down Capone, but Ness was more of a pencil-pusher now. As The Washington Post notes, he certainly didn't have much on-the-ground experience as a detective. Still, once the seventh victim was uncovered, Ness was officially assigned to the case in September 1936.

Ness faced serious issues during the investigation

Though the bodies uncovered in 1935 and 1936 were horrifying enough, the killings didn't stop there. In the next year, as reported by the Cleveland Police Museum, a woman's torso was found in February 1937. In June, two sets of skeletal remains were discovered beneath a bridge, including the killer's only known Black victim, a woman probably in her 40s tentatively identified as Rose Wallace. The ninth victim, an unidentified man, came to attention in July when a guard saw remains floating in the Cuyahoga River.

The killings continued into 1938 when a woman's remains were found in pieces in April. Another woman's torso was uncovered in August, with her disassembled legs, arms, and head nearby. Along with a second body, the August remains were left in the sight of Ness' office window. The Cleveland Torso Murders would prove to be a major stumbling block for Ness, according to The Washington Post. As he faced dead end after dead end, Ness' drinking increased, along with his extramarital affairs and even downright illegal activities, like committing a hit-and-run while under the influence and even hiring someone to shoot a gun in a club as a poorly considered joke.

The search for the killer led to the burning of Kingsbury Run

Apart from his failure to catch the killer, Ness' greatest slip up in the investigation arguably came after he entered Kingsbury Run himself. In August 1938, after the twelfth and apparently final victim had been discovered, Ness and 35 police officers descended upon the shantytown of Kingsbury Run. As per the Cleveland Police Museum, the raid also included a cluster of 11 police cars, two vans, and three fire trucks, undoubtedly drawing plenty of attention to the goings-on. Starting at 12:40 a.m. and working until the sun rose, Ness' group apprehended 63 men and then searched amongst the structures for any clues that might help them identify the killer.

After finding next to nothing, Ness made another major misstep, at least in the eyes of the press and the citizens of Cleveland: He ordered the shanties burned. With the people of Kingsbury Run left truly homeless, Ness was lambasted in the newspapers. Cruel as his actions were, the killings did apparently stop, though it's unclear if the police department's arson was the cause.

One suspect may have been forced to confess

Only one man was ever arrested in connection with the Cleveland Torso Murders. Yet, his arrest, interrogation, and ultimate fate have been the subject of controversy for decades. According to Cleveland Magazine, that man was Frank Dolezal, arrested in July 1939. Initially, he confessed to the murder of one of the few identified victims, Florence Polillo. However, Dolezal later withdrew his statement, saying that sheriff's deputies had beaten him in order to force a confession. He wasn't able to offer much more information, however, as he was found dead in his jail cell just a month later, in August 1939. The coroner said that Dolezal died by suicide, but later researchers wonder if the recalcitrant suspect might have been murdered. The county coroner found that Dolezal had six broken ribs, an injury he incurred after entering police custody (via Cleveland Police Museum).

Perhaps Dolezal, who was an immigrant and manual laborer, was unfairly targeted. In fact, Torso Murderer researcher and expert Dr. James Badal has said (via Scene) that he is pretty confident Dolezal was wrongfully pinned for the crime. Indeed, Badal noted that even the lead detective on the case thought it strange that the accused killer knew practically no details about the crime he had supposedly committed.

If you or anyone you know is having suicidal thoughts, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline by dialing 988 or by calling 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

Another suspect was kept secret

If Frank Dolezal was wrongfully accused, then that meant the killer had escaped attention. Or had he? According to Cleveland Magazine, Dr. James Badal uncovered evidence that Eliot Ness had actually found a serious suspect and interrogated him in 1938. That man was Francis Sweeney, a World War I veteran and doctor who was in the right place and time to commit the murders and precise dismemberments seen in some of the victims (via "In the Wake of the Butcher"). One transient, a man named Emil Fronek, even claimed that an unnamed doctor in Cleveland tried to drug him back in 1934 when the Lady in the Lake (possibly the first victim of the murderer) was found.

Ness took Sweeney to a local hotel for an interview, though it reportedly took days for the alcoholic doctor to sober up enough for a lie detector test — which he failed twice. When he later committed himself, the killings stopped. But he had powerful relatives and there was never clear evidence that he had a base near Kingsbury Run. A case brought against him was all but certain to collapse in court. Yet, there is evidence that he sent eerie postcards to Ness, teasing involvement in the murders. He was diagnosed with schizophrenia in 1956 and died in 1964 (via Cleveland Magazine).

Some think there was more than one killer

While killer drifters and knife-wielding doctors are pretty terrifying, one of the last prominent theories regarding the Cleveland Torso Murderer's identity may be the most frightening of all. What if the city was stalked by not just one bloodthirsty killer, but many?

This theory hinges on the coroner's reporting. Cuyahoga County Coroner Arthur J. Pearse may have misidentified some of the injuries on the murderer's victims, concluding that some were the precise work of someone with medical training when they may have been more slapdash (via "In the Wake of the Butcher"). It doesn't help that the next coroner, Samuel Gerber, seemed to enjoy the attention that eye-popping theories got him. Moreover, there was enough variation in the killings, with some victims appearing to have been killed elsewhere and then placed in Kingsbury Run, while others appear to have been found where they died. Was this the work of an increasingly sloppy killer, or evidence of multiple murderers with different methods? Though investigators at the time seemed convinced that the killings were the work of a single person, there remains enough doubt to convince some that whoever was out there wasn't working in isolation.