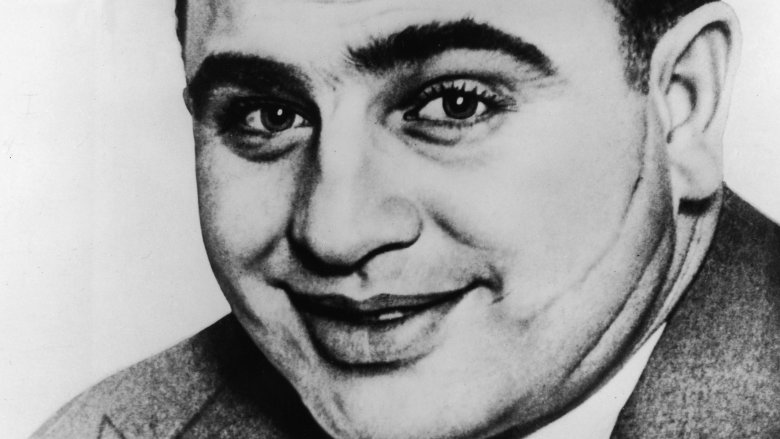

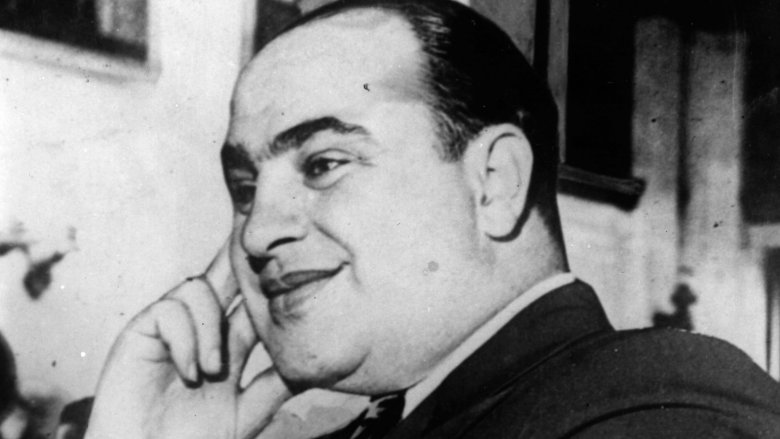

The Untold Truth Of Al Capone

His name was Alphonse Gabriel Capone, but everybody knew him as Al. Born in 1899, Capone grew up in New York, and as a teenager, he quickly fell into a life of crime. He was mentored by mobster Johnny Torrio, and after the older hood set up shop in Illinois, he quickly sent for his young protégé.

Together, Torrio and Capone ran the Chicago Outfit, a gang that controlled the south side of the Windy City. After Torrio retired in 1925, he left control of the gang to his right hand man. And the rest, as they say, is history.

With Prohibition in full swing, Capone quickly became the biggest bootlegger in American history. As the nation's number one bad guy, the man was involved in everything from prostitution to gambling to alcohol. Soon, Capone had amassed a $100 million fortune, to say nothing of his impressive body count.

While Capone was only king of the Chicago mob for six years, his name is synonymous with the word "gangster." Over seven decades after his death, he's still considered an American crime icon, one who's left behind a fascinating history of blood, bullets, and booze.

How he got the scars

Al Capone had a lot of nicknames. The city of Chicago called him "Public Enemy No. 1," although he liked it better when people called him "Snorky," which apparently meant well-dressed. Meanwhile, most knew Capone by a completely different nickname: Scarface. The gangster sported three prominent scars on the side of his neck and left cheek, and they gave him a pretty intimidating look. But what's the story behind the mobster's marks?

Well, as a young man, Capone worked for Frankie Yale, a crook who ran a New York bar called the Harvard Inn. Yale hired Capone to work as a bouncer, and then one fateful evening, the 18-year-old Al spotted a girl named Lena across the bar. Capone tried asking her out, but she turned him down — twice. But then, as Lena was leaving, Capone tried out one last line. "I'll tell you one thing," Capone said, "you've got a nice a**, honey, and I mean that as a compliment."

Well, Lena didn't take it as a compliment, and neither did her brother, Frank Galluccio. Infuriated, Galluccio pulled a knife and went to work on Capone's face, slashing him to ribbons and forcing Capone to get 80 stitches. Frankie Yale intervened before things could get any more violent, brokering a peace deal between the two hoods. And evidently, Capone could be a pretty forgiving guy, when he wanted to be: he later hired Galluccio to work as his bodyguard, paying the guy $100 a week.

Of course, Capone didn't like telling the truth about his scars, so whenever people asked, the crime lord would say he was injured in World War I...a war he didn't fight in.

His supervillain lifestyle

Just like a mobster ripped from a Dick Tracy comic, Al Capone lived like he was some sort of supervillain. In the early part of his crime lord career, Capone camped out in the Hawthorne Hotel. While it was theoretically a spot where guests could spend the night, most stayed far away, as the place was filled with Capone's crew. The ground floor was full of machine gun-toting thugs, and according to author Deirdre Bair, the windows were covered with bullet proof shutters. And then there was the Lexington Hotel, a hangout full of trap doors, sliding walls, elaborate alarm systems, and escape tunnels. It was the perfect castle for a criminal kingpin.

Capone also camped out in a smaller apartment, one with a steel reinforced door. The joint was surrounded by a brick wall about eight feet high, and there was even a tunnel leading from Capone's home to his garage, where he could quickly climb into the coolest car in criminal history. If you want to get specific, this thing was a 1928 Cadillac Model 341A Town Sedan, and it was the ultimate anti-cop automobile. This three-and-a-half ton car was covered in steel, and all the windows were made of bulletproof glass. Better still, a trigger-happy gangster could lower the rear window and aim a Tommy gun at any cops in hot pursuit. Of course, if Capone needed to make a getaway, his Cadillac could hit 110 mph, but it's not like authorities could just sneak up on him. There was a police radio in his car so he could spy on their calls, and if he never need to blast through traffic, he even had his own police siren ready to go.

His brother was a Prohibition agent

Al Capone had quite a few brothers — some of whom were involved in the family business — but James Vincenzo Capone made a completely different career choice. After leaving New York at a young age, James made his way out West, arriving in Nebraska in 1919. Inspired by Hollywood cowboy William S. Hart, the older Capone brother started wearing spurs, ten-gallon hats, and ivory-handled revolvers. He even changed his name, calling himself Richard "Two Gun" Hart.

Hart let his Nebraska neighbors believe he was part-Indian, and soon, the man was a legend across the state. A deadly accurate marksman, Hart became a Prohibition enforcement agent, going undercover and busting up stills. This guy tracked down murderers, got into fist fights with bootleggers, and once rescued an entire family from a flash flood. And in true romance novel fashion, a woman he pulled from the water married him just a few months later. Eventually, Hart would be tasked with catching moonshiners on Indian reservations, and once, he even served as President Calvin Coolidge's bodyguard.

Later in life, things got rough for Hart. He was fired after killing a fugitive, suffered from failing eyesight, and soon found himself out of money. Desperate, he eventually asked for some cash from his brother Ralph, a guy very much involved with Al's operations. Hart and Scarface himself reunited in 1939, after the crime boss was freed from Alcatraz. Then in 1951, the government subpoenaed Hart to testify against Ralph, and the Prohibition agent was finally forced to admit he was a Capone. Hart passed away at the age of 60 in 1952, just five years after his infamous brothers.

The story behind the St. Valentine's Day Massacre

The Beatles have Sgt. Pepper, Orson Welles has Citizen Kane, and Al Capone's got the St. Valentine's Day Massacre. This magnum opus of murder went down on February 14, 1929, but really, the trouble behind the massacre had been brewing for years. See, Chicago was divided between two gangs. There was Capone's Italian outfit in the south, and the Irish mob in the north, run by George "Bugsy" Moran. There was bad blood between the two that went back for years, involving multiple mob bosses and more than a few machine guns.

Eventually, Capone decided to end it all by sending Bugsy a love letter made out of lead. On February 14, seven members of Moran's North Side gang showed up at a garage on 2122 N. Clark Street. They were there to buy some whiskey from a bootlegger, but unfortunately for these guys, it was all one big set-up. Once they stepped inside the garage, four or five men showed up on the scene, some dressed as police officers, others wearing trench coats. Probably thinking this was a raid, Moran's men didn't fight back when the "cops" ordered them up against a wall. Seconds later, their bodies were riddled with bullets. Armed with shotguns and Tommy guns, Capone's men unloaded 70 rounds, which has got to be the world's worst Valentine's present.

Capone's men then made their escape, but the hit wasn't 100 percent successful. It seems Moran was late for the appointment and took off when he saw the "cops" at the garage, a decision that saved him from a machine gun massage. But even though he escaped with his life, the St. Valentine's Day Massacre was basically the end of the North Side gang, giving Capone complete control of the city. Nobody was ever arrested for the crime, and no one could prove Scarface was behind the murders, as he'd been in Florida at the time of the shootings, soaking up some sun.

The nice side of Capone

On December 25, 1925, Al Capone and a couple of his goons ambushed a group of rival gangsters at a Christmas party, sending them on a one-way trip to meet baby Jesus. The incident was known as the Adonis Club Massacre, and it's possible that Capone personally offed one of his victims with three shots to the head.

But behind the violence and beneath those scars, Al Capone had a soft side, especially when it came to his son, Albert "Sonny" Capone. When Sonny was a boy, he suffered from serious ear infections, and Capone made sure his kid received the best treatment available. And after Capone was locked up in Alcatraz, he sent Sonny some pretty affectionate letters. "Junior," Capone wrote, "keep up the way you are doing, and don't let nothing get you down." He also recommended that Sonny spend his time listening to music and reading Fortune magazine before signing off with, "Love & Kisses, Your Dear Dad Alphonse Capone #85." (That was his number in the slammer.)

Capone also helped out the less fortunate by opening a soup kitchen for Chicago's poor and unemployed, a charity that often fed up to 3,000 people a day, which ain't too shabby. And like any other businessman, Al Capone loved playing a few rounds of golf. However, according to his caddie, Tim Sullivan, Capone "played a terrible game" and "couldn't putt for beans." That's possibly because Capone and his buddies would often get drunk whenever they were on the green. Of course, golfing with gangsters can get dangerous, and according to Sullivan, Capone accidentally shot himself in the foot during a game, thanks to a loaded pistol that went off inside his golf bag.

Eliot Ness and the Untouchables

Even though he was the most famous crook in America, Al Capone was incredibly difficult to catch. The mobster was skilled at distancing himself from anything illegal, and it was almost impossible to prove he was earning money from his criminal enterprises. The paper trail was nonexistent, as he only dealt in cash, and the man didn't even have a bank account. Sure, he once served nine months on a concealed weapons charge, and he was sentenced to six months for contempt of court, but Capone was never locked up for long. That's probably because Scarface spent millions buying friends in high places, and since most ordinary folks were too scared to testify, Capone lived beyond the law.

But not every cop in Chicago was corrupt. Take Prohibition officer Eliot Ness, for example. One of the few clean men in a dirty city — even if he did imbibe from time to time — Ness headed up a crew of agents known as "the Untouchables," so-nicknamed because they refused to accept bribes. While their impact has been exaggerated in pop culture, the Untouchables were definitely a pain in Capone's side, as they made a habit of busting up his breweries.

As a result, the mob tapped Ness' phone, repeatedly stole his car, and filled one of his informants full of lead. But according to The Washington Post, the Untouchables soldiered on, building a "5,000-count bootlegging indictment" against the crime lord. However, despite Ness' hard work, the Untouchables weren't the ones who brought Capone down.

What brought Capone down

Instead of hitting Scarface with bootlegging charges, the federal government decided to focus on the mob boss' income taxes. After all, the feds figured tax evasion would play better with a jury, since everybody loved booze and hated Prohibition.

The FBI, the IRS, and the Treasury Department spent a lot of man hours linking Capone to his illegal establishments, and luckily, they discovered he'd once endorsed a check related to his gambling business. That, coupled with the testimony of a few brave souls, was enough to build a case, and in 1931, Capone was put on trial. Sure, he tried bribing the jury, but ultimately, Capone was convicted on five counts of income tax evasion, earning the 32-year-old 11 years behind bars.

Capone in prison

Life in the slammer was pretty easy for Al Capone...well, at first anyway. The gangster was initially shipped to the Federal Penitentiary in Atlanta, and the kingpin basically had his run of the joint. He had his own radio, he had his own carpet, and he kept a whole lot of moolah lying around so he could bribe the guards for favors. The warden was at his beck and call, and he was allowed visitors every single day. But that all changed in 1934, when Scarface was sent to Alcatraz.

Things on the Rock were a bit different for Capone. Alcatraz's warden didn't play games. Instead of lounging in luxury, Capone spent his days working in the laundry or mopping up the showers. The mob boss also found he was pretty low in the Alcatraz pecking order. For example, when Capone refused to take part in a prison-wide protest, two separate inmates attacked him on two separate occasions. Another time, Capone made the mistake of trying to cut in line at the prison barber shop. This didn't sit well with bank robber James "Tex" Lucas, who would later teach Capone about prison etiquette by slicing up the gangster with half a pair of scissors.

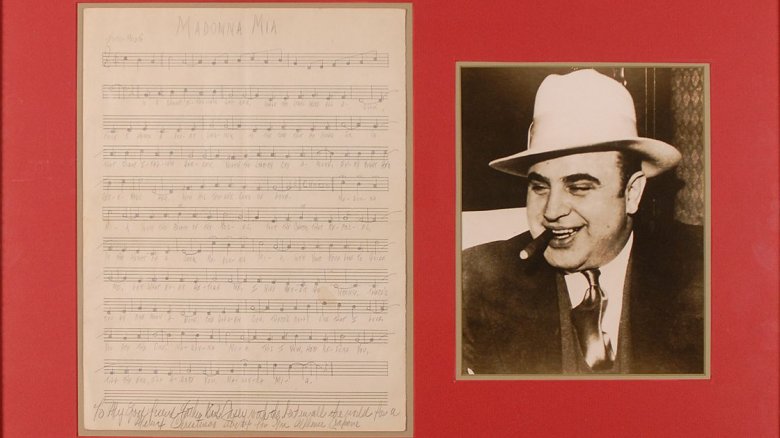

Al Capone: songwriter

Capone's life on the Rock wasn't all bad. The warden did give Capone permission to start his own band, a little group called The Rock Islanders where Capone played banjo. And when he wasn't enjoying baseball, horseshoes, or checkers, Capone was writing love songs. Yeah, that's right. During his time in Alcatraz, the world's greatest gangster wrote at least one little ditty called "Madonna Mia." Most believe it's about his wife Mae, and the song includes lyrics like, "Madonna Mia, you're the bloom on the roses, you're the charm that reposes, in the heart of a song. / Madonna Mia, with your true love to guide me, let whatever be-tide me, I will never go wrong."

That's shockingly sappy for the man behind the St. Valentine's Day Massacre, but it just goes to show that even notorious murderers can have a romantic side.

Capone's final days

While Al Capone was sentenced to 11 years in prison, he only served about seven. The gangster was paroled in November 1939, but it wasn't like he could enjoy his new freedom. See, Capone was released from Alcatraz because he was suffering from a devastating case of syphilis. Scarface had contracted the disease back when he was about 20, working as a bouncer at a Chicago brothel. Too embarrassed to seek medical help, Capone let the disease rage unchecked until the infection made its way into his brain.

Inside Alcatraz, Capone began showing signs of unusual behavior. He would sometimes wear a heavy coat and gloves even though his room was boiling hot, and he claimed to own a factory that didn't actually exist. The gangster was eventually diagnosed in 1938, and the doctors tried curing him by infecting Capone with malaria, hoping the insanely high fevers would kill the bacteria. Unfortunately for Al, that treatment didn't work. When he was released, he sought help at Baltimore's Union Memorial Hospital. Wanting to reward the doctors and nurses who tried to cure him, Capone bought the hospital two weeping cherry trees, one of which is still there today.

The death of Al Capone

Despite Baltimore's best efforts, Capone was incurable, and soon, his mind was reduced to that of a 12-year-old boy's. In his final years, Capone lived with his wife at his Florida home, but unfortunately, the man was totally broke, living off an underworld stipend of just $600 a week, a far cry from the millions he once spent. Even worse, Capone spent most of his time talking with people who weren't really there. Finally, the infamous Al Capone—sick, tired, and confused—died in January 1947 at the age of 48 after suffering from a stroke, pneumonia, and cardiac arrest. And even though he once ruled Chicago with an iron fist, only a handful of people showed up to his funeral.

The Geraldo Rivera fiasco

April 21, 1986 was supposed to be a big comeback for Geraldo Rivera. The TV personality had recently been fired from ABC News, and now he was hoping to hop back into the limelight with a little help from a dead gangster. As it turns out, underground tunnels had been discovered beneath Capone's old hangout, the Lexington Hotel, and with the help of producers Joslyn and Doug Llewelyn, Rivera was going to excavate the ruins and see what treasures Scarface had hidden beneath the city streets.

Titled The Mystery of Al Capone's Vault, this two-hour live show featured talking head historians and old-timey footage interspersed with scenes of Rivera firing a Tommy gun. Hoping to build suspense, Rivera had IRS officials and crime scene investigators on-scene, just in case he discovered some of Capone's cash or a stack of dead bodies. But after using dynamite to blast away a wall, Rivera stepped inside the passageway to discover a whole lot of...nothing. Other than dirt and a couple of bottles, the place was completely empty.

Yeah, it was a major embarrassment, but despite the disappointing ending, The Mystery of Al Capone's Vault was watched in 30 million homes across America, beating out major TV shows like The Cosby Show and Family Ties. So while it was a major fail, the show definitely gave Rivera's career a boost, and the man can still be seen on TV today, all thanks to Al Capone.