The Messed Up Truth About Spain's Stolen Babies

In Spain today the scars of Francisco Franco's fascist government are still acutely felt. While fascism in Spain ended with Franco's death in the mid-70s, many families were quite literally torn apart by the regime. Today thousands of Spanish citizens who were stolen as children and given away to other families are still in search of their birth parents. Thousands of others may still be blissfully unaware that they were adopted (via NPR).

The scale of the kidnappings in Spain has only come to light fairly slowly over the last few decades. In 2002, an explosive book entitled "The Lost Children of Francoism" highlighted a series of individual kidnapping cases per The Guardian, then in 2011, 261 families came forward, in an attempt to get their cases heard according to The Guardian's reporting.

In 2012, a nun was indicted for involvement in the kidnappings (via The New York Times), although she never attended court and died shortly after. Finally, in 2018, one of the alleged perpetrators was brought to trial at last — an elderly doctor who was subsequently released.

Desirables and undesirables

But why were so many children kidnapped in Spain and who were they given to? During Franco's time, the country was characterized by its hardline religious conservatism. Contraception was banned and women were expected to focus solely on being good wives and mothers. Unable to even open a bank account (via NPR), they were encouraged to make themselves model housewives, following guidance from Franco's government (via The New York Times).

But Spain was (and still is) a very politically divided country, so much so that even today, many people say there are "two Spains" (via The Berkley Center). During the Spanish Civil War Catalonia was once filled with anarchists (via the UCLA Library), and Spain's pre-war democratic government was unusually progressive. The fascist regime was therefore stuck with many determined enemies.

Under Franco's government, Spanish women were encouraged to breed — but what happened when the "wrong" sorts of people had children? Rather than letting leftist radicals and known liberals outbreed them, babies were simply stolen and sold off to "respectable" women (via The Guardian). Some of the mothers who appear in "The Lost Children of Francoism" and who fell victim to kidnapping include a known communist and a woman whose father was part of the resistance against Franco (via The Guardian). Other women were targeted simply for being poor or unmarried (via El Pais).

Covert operations

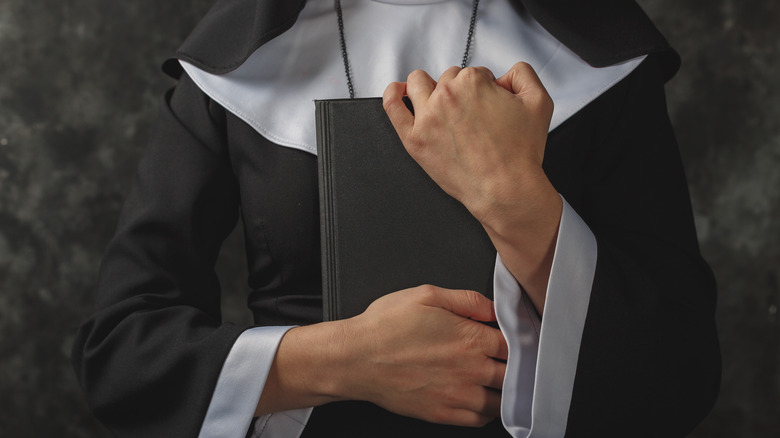

A secretive group of doctors and nurses — and perhaps even more shockingly priests and nuns — were involved in the kidnappings that took place over a period of roughly 50 years (via NPR). Typically a doctor or nun present at the birth would take the baby away from its parents the moment it was born. Upon their return, the kidnapper would concoct a story that the infant had died or had arrived stillborn (via The New York Times).

In effect practicing a form of eugenics, babies were redistributed to well-to-do Catholic families and sometimes even sold abroad (via The Guardian). Coffins were buried empty in some places (via Business Insider), and fake adoption papers were created to disguise the clandestine baby-stealing operation. A great many people were taken in by the ruse, while others were gaslighted into believing the story. It is only in recent years that many people have once again come to question whether the children they lost really died in childbirth.

The great forgetting

Unfortunately, getting justice for the victims has been a challenging road. Many things about Spain's fascist government have been kept under wraps since Franco died in 1975. In order to draw a clean line under the dark events of the fascist period, Spain passed an Amnesty Law in 1977 (aka the Pact of Forgetting), which let those who had committed crimes under the old government off the hook (via Reuters).

The Amnesty Law has been called into question ever since, and Spain has previously come under fire by U.N. for not investigating a swathe of missing person cases. Many people deemed undesirable to the regime, ended up in mass graves, never to be seen again.

The child kidnapping cases also appear to have continued even after the regime ended, well into the '80s. According to NPR as of yet, it is not known to what extent the trade in babies was backed by the fascist government, and to what extent it flourished as an underground money-making operation.

DNA evidence

According to the Independent, in 2021, human rights charity Amnesty International confirmed that at least 51,266 cases of kidnapping had taken place. Some sources estimate that the true number is closer 300,000 (via Time).

Amnesty International continued to put pressure on the Spanish government to investigate the claims more closely — and they seem to have gotten their wish. Spain's left-wing government, which came to power in 2018, has introduced new measures to dig into old crimes (via The Local).

In 2018 a DNA database and investigatory committee were created to help reunite families. Furthermore, as of 2022, a "democratic memory law" has been passed, giving the authorities new permission to investigate wrongdoings from the fascist era. The law will be used to further investigate the case of the stolen babies, as well as mass graves that have gone ignored for decades. The measure was met with considerable opposition from right-wing parties across the country.

An uncertain future

Today, the investigation poses many difficulties for those involved. A surprisingly large number of people whose cases have already been investigated have since discovered that they were not actually victims (via El Pais). On the other hand, some victims will not even be aware they have cause to investigate — as in a case recently reported by The New York Times, in which a woman only discovered she was adopted only by stumbling across some of her mother's old papers. Amnesty International has also drawn attention to the fact that many of the stolen children may be abroad somewhere, and therefore difficult to trace (via The Independent).

Furthermore, not everybody in Spain is happy to go digging up the past. Spain's right-wing People's Party has vowed to reverse the new democratic memory legislation in the event they get elected (via The Guardian). The investigation into the Catholic Church's role in the case — and its role in other crimes committed by the fascist government — is also sure to cause a great deal of controversy.