Why Experts Don't Agree On The Death Toll From The Black Plague

The COVID-19 pandemic of 2019-2022 reminded the world of just how serious contagious illnesses can be and how, even in the modern era, we humans are still vulnerable to organisms we can't see without specialized equipment. Fortunately, thanks to vaccinations and modern therapies, we have a handle on most contagious illnesses these days. Dread diseases such as tuberculosis, cholera, and smallpox — which at one time killed indiscriminately — are now either things of the past managed pretty well (at least in the developed world).

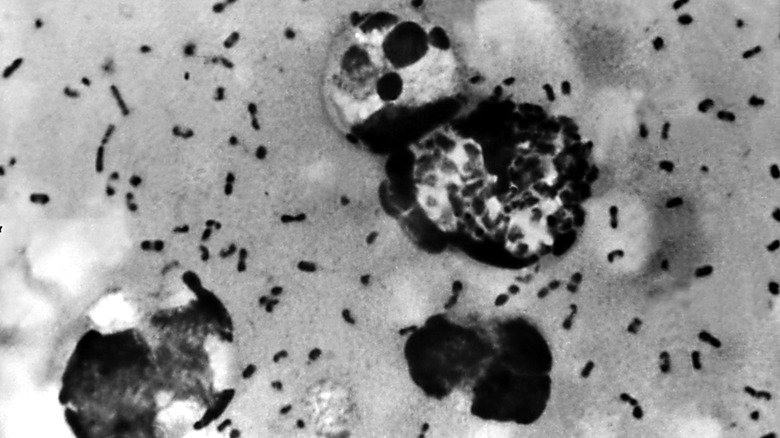

One dread disease of the past that is still around is the bubonic plague (often historically and colloquially referred to as the "Black Plague" or "Black Death"). According to the Centers for Disease Control, about seven Americans are sickened by the bacterium that causes it — Yersinia pestis — per year, although modern antibiotics mean it isn't the death sentence it once was. That should be of little comfort to the tens of millions of people who died of it in Europe over the course of 11 or so centuries, in particular during the Black Death of 1346-1353. For centuries, it was just accepted scientific dogma that the 14th-century outbreak killed tens of millions of people, roughly half the population of Europe at the time. However, according to All That Is Interesting, some scientists aren't convinced these numbers are accurate, based on recent research by teams looking at how the epidemic affected farming and the environment.

Yersinia Pestis and Repeated Plagues

On at least three occasions in history, the plague struck Europe with a vengeance (and this says nothing of the likely hundreds if not thousands of smaller, localized outbreaks of the disease over the centuries). The first was the Justinian plague of 542-750, the next was the Black Death of 1346-1353, and the third was the Great Plague of London in 1666.

The 14th-century outbreak of the disease was, by far, the worst in terms of lives claimed; it also brought about long-ranging effects (not all of them bad) on Europe's commerce, cultural landscape, and religious landscape, according to the University of Florida. This outbreak also changed the natural environment, albeit indirectly. As All That Is Interesting explains, humans can generally be counted upon to leave indelible marks on the environment whenever they settle, and the results of that human activity can be preserved for centuries afterward. Even microbes can tell the tale of what they did and when they did it when studied against other clues. And in Europe, those microbiological clues suggest that the Black Death actually left large parts of Europe completely unscathed, according to some researchers.

Estimates Of The Black Plague's Death Toll

The Black Death of 1346-1353 actually came in two waves, according to New Scientist: It subsided for a while in 1351, then returned "with a vengeance" a few years later. When the dust had settled, an estimated 50 million people were dead, or between 30-50% of the population, according to The Conversation.

How do we know this? Well ... we don't know for certain, actually, for a variety of reasons, not the least of which is that it happened 700 years ago. These estimates are based largely on the written documents that survived the centuries, and the only people who could write in those days were the aristocracy and officials in the Church. Records from some places, such as Italy, are about as thorough as can be expected when it comes to this sort of historical epidemiology. In places such as Poland, however, not so much. Filling out the rest of the picture is largely a matter of educated scientific and historical guesswork that relies on multiple avenues of study. And one such avenue of study is the effect humans left on the environment.

How Pollen Provides Us With Clues

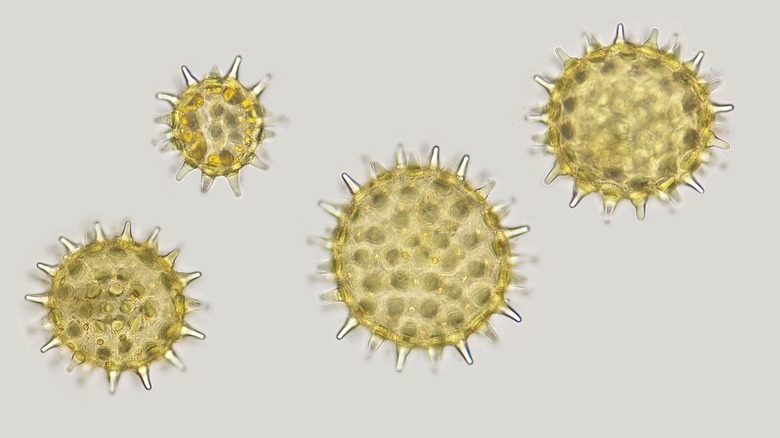

Pollen is one of those things in nature that we at once hate and can't live without. Sure, it may be foundational in keeping plants and the ecosystems that rely on them functioning, but it also bedevils many of us with allergy symptoms every change of seasons. As it turns out, pollen spores are also extremely helpful in looking at the history of humans and their relationship to the environment. Specifically, as The Conversation explains, different plants produce different grains of pollen. What's more, if pollen spores land in the right place — say, in a lake or the boggy soil of a wetland — they will be preserved for centuries.

Now, here's a thought experiment: If a bit of land is subject to human activity, such as farming crops, then the botanical record would include a lot of pollen from plants that humans grow, such as wheat and rye. But if human activity comes to a stop — from, say, a devastating plague that wipes out large swaths of the population — then there should be more pollen from naturally-occurring plants than from cultivated ones. At least in theory.

Exploring this avenue of thinking, a team of researchers took a look at pollen counts from various places around Europe and concluded, as they report in Nature, that some parts of the continent were left almost completely unaffected.

So Maybe It Wasn't That Bad After All?

As Dr. Adam Izdebski and his team wrote in Nature, researchers went to 261 locations in Europe and started collecting samples and looking at the data. And what they came up with ... well, it doesn't rewrite history, but it certainly challenges what was once basically scientific dogma. We're leaving out quite a bit of the science here, but the long story short is that as far as can be gleaned from pollen samples, the Black Death did not affect all of Europe equally. According to All That Is Interesting, of the 19 countries in which researchers collected data, only seven of them contained evidence to indicate that people there died off in large numbers, as evidenced by their fields being left to go fallow and/or return to nature. Other places across the continent saw no change in human activity, and some actually saw increases in human activity.

"This means the Black Death's mortality was neither universal nor universally catastrophic. Had it been, sediment records of Europe's landscape would say so," the team wrote (per All That's Interesting).

Some Scientists Aren't Convinced

Science isn't rewritten with the stroke of a pen, particularly when it comes to science that has generally been accepted as fact for decades. So when it comes to estimates of the death toll of the Black Death of the 14th century, not everyone is fully buying into this new research. Dr. Adam Izdebski and his team, for their part, were quick to point out that their conclusion about the plague's spread is a separate matter from any conclusions that could be drawn about its impact. "Not only will societies be affected and be able to respond differently, but we should not expect plague to always spread in the same way or for plague pandemics to be easily sustained," they wrote (via All That Is Interesting).

John Aberth, author of the book, "The Black Death: A New History of the Great Mortality," said via The New York Times that Europe was so interconnected in those days via trade and conquest that it's all but impossible that huge swaths would be unaffected by the epidemic. He also said that immigrants might have come in to pick up the slack in places where the agricultural workforce was devastated. Similarly, historian Monica Green is of the belief that the plague was caused by two strains of Y. pestis, and parts of the continent may have suffered less due to the weaker strain — but they still suffered.