Square Dancing's Roots Aren't As Wholesome As They Seem

Club square dancing organizations across the U.S. host western-style, liquor-free dances brimming with family values and their own brand of American heritage (via Quartz). Who wouldn't be a fan of the wholesome activity known in America as square dancing? Popular with an older clientele, this recreational activity is the official dance in 28 states (via Net State). The clubs briefly trotted their dance style to national emblem status in 1982 and 1983, when it was declared the temporary national folk dance (via The United States Congress).

But square dancing is a lot less traditional than you've been led to believe (via Washington City Paper). It might not even be a folk dance. According to "The State Folk Dance Conspiracy: Fabricating a National Folk Dance," by Julianne Mangin, what represents square dancing today is a version called Modern Western square dance or club square dance. By 1965, club square dancing was the most dominant form, the faux-cowboy attire being a wholly recent convention (via The Chicago Tribune). According to Joe Wilson, the executive director of the national council for the traditional arts, club square dance "goes back to the 1920s at the earliest."

This dance craze, resurrected decade after decade, arguably "has nothing to do with the nature of folk dance in the United States." And perhaps without anti-Semitic Henry Ford's efforts to fight what he saw as the evil international Jewish cabal, generations of students across the country wouldn't be familiar with this square shaped form of physical education.

Dance clubs push an agenda

When clubs tried for permanent status in a 1988 Congressional bill, their legislative push stepped on the toes of folklorists nationwide (via Quartz). In the 1988 hearing, dance historian LeeEllen Friedland testified, "the regimented steps were developed and standardized through recreational organizations ... and not through the folk process to which all cultural traditions are subject" (via "The State Folk Dance Conspiracy"). After the bill was rejected, the U.S. Square Dancers and the American Folk Dance committee of LEGACY turned to state level status (via Quartz). There was little resistance to pass through. The official state folk dance was a fabricated position with no competition. The bills provided policy makers with a fluffy piece of legislation supporting American values and a chance to host national competitions.

Again, dance and folk experts pushed back at the various hearings. Making any art form officially recognized "denies the diversity of cultural, ethnic and social traditions in America," argued columnist and dance caller Eric Zorn in 1990 (via The Chicago Tribune). As statesman Stan Fowler keenly observed in Maryland, what's the point of having a state dance if it's not unique or special to one's state?

But if experts assert club square dancing isn't of national or state folk origins, where did it come from? If you think an unrelenting legislative steamroller steered by square dancing senior citizens sounds ominous, wait until you hear about another square dance-centered conspiracy theory.

Ford's dance obsession goes national

Square dancing was all but extinct by the 1920s, until capitalist Henry Ford launched what the Detroit News called at the time "a comprehensive plan ... to nationalize a revival of the old dances, particularly emphasizing the square dances" (via The Journal of the Society of American Music). The same man who openly proclaimed that "history is bunk" also pined for the dances of his youth (via Steven Watts' "The People's Tycoon: Henry Ford and the American Century").

While on a cross-country vagabond foray, Ford stumbled upon Massachusetts' Wayside Inn and its dance programmer, Benjamin Lovett. Ford enjoyed square dances and "music which none of us had heard for 20 years." To insure a steady stream of nostalgia, Ford purchased the hotel, and Lovett's contract with it (via America's Library and the Library of Congress). Taking Lovett back to Detroit, they established a "program for teaching squares and rounds."

After forcing his employees to attend formal dance events, Ford went nationwide (via Quartz). His self-funded campaign revitalized the recreational activity and defined 1920s country music (via University of Chicago Press). It was the summer dance fad of 1925, with enthusiastic press coverage, radio play, and fiddling contests hosted by Ford dealerships. Ford and Lovett were the original progenitors of school-taught square dancing programs across the nation, believing it offered "social training, courtesy, good citizenship, along with rhythm." By 1928 nearly half of American schools had it on their curriculum.

Ford, jazz, and square dancing

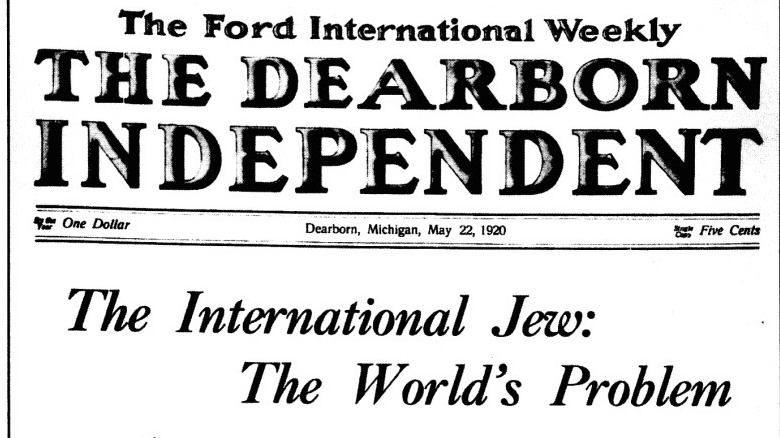

This campaign was going smoother than the anti-Semitic rhetoric Ford had put forth only a few years previously (via The Journal of the Society of American Music). In 1920 and 1921, before the fiddling contests, Ford dealerships featured his national magazine, which ran a series titled "The International Jew: The World's Foremost Problem." We know Ford was deeply anti-Semitic (via Quartz). Apparently, part of the imagined international plot involved saxophones and the dance known as the Charleston. In an article titled "Jewish Jazz Becomes Our National Music" and "How the Jewish Song Trust Makes You Sing," writers asserted that jazz music was an entirely Jewish-constructed art form, created with the purpose of weakening western society.

While these pages won the esteem of Adolf Hitler and his political allies, the paper had little local impact. Other than a small boycott, the Jewish community mostly ignored the publications.

While many see purposeful design, other historians find no causal relationship connecting the anti-jazz and anti-Jew rhetoric of Ford's publications and his push for alternative recreational activities only four years later. When asked directly, Ford claimed to have nothing against jazz. The tycoon claimed, "I'm not setting out to reform anything or anybody."

Dance parties of the 1800s featured enslaved performers

Ford fondly recalled the quadrille, waltzes, and reel dances of his misty water-colored past (via The Journal of the Society of American Music). So where did those various pieces and accents of this art form really come from? It's likely that Ford would blanch to find out the true origins of his favorite dances. The trademark call and response of his beloved dance came from the enslaved Africans of early America. The movements or figures of square dancing began in England and Scotland — country or contra dances and less formal reels (via Journal of Appalachian Studies). Once in the Americas, elements of the French quadrilles dance forms were added (via Jstor Daily).

At the balls and dancing schools of early American white colonists, enslaved Blacks provided musicians, such as fiddlers, and dancers. Whites would go on the floor with memorized dance routines and enslaved Blacks would play music. Over time, the enslaved started to put their own spin on the dancing. Their influence can be detected in drumming elements traditional to their African cultures of origin.

The beginning and end of square dancing, perhaps

Calling was a common element of dancing in Black culture before it was introduced to white events in the late 1700s or early 1800s by African-American musicians (via The Journal of Appalachian Studies). The call-and-response perhaps helped to organize the dancing and likely allowed the Black performers to replicate a dance without training (via Quartz). The first recorded case of Black callers at a white event dates back to 1819 (via Jstor Daily). Over time, white callers edged out the Black callers in popularity. This is likely the origin of major regional folk forms the Northeastern and the Southeastern square dance (via "The State Folk Dance Conspiracy").

The power of any modern western square-dancing must be waning. As of 2018, the former mainstay of physical education classes is missing in most American schools (via Country Dancing Tonight). The United Square Dancing Association website says that their national campaign to make square dancing the official folk dance of America is on hold until there's support to submit a new bill. However, when it comes to declaring national or state wide art forms, many folk art enthusiasts are still saying do-si-don't.