Who Was Mary Surratt, The First Woman To Be Executed By The US Government?

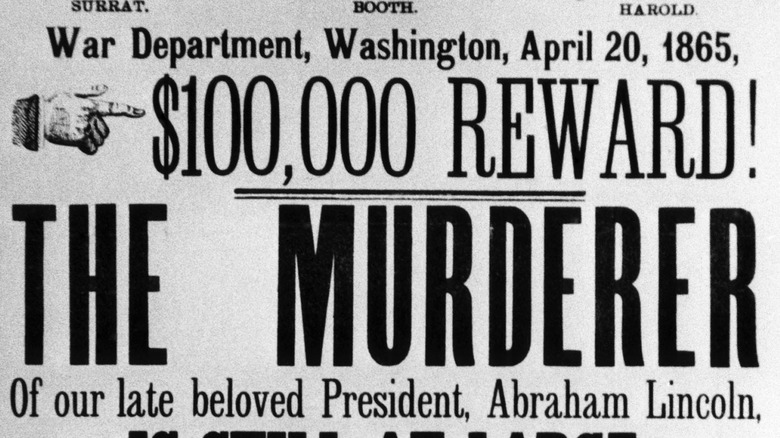

On July 7, 1865, four condemned criminals (per Washingtonian) were marched in chains to the scaffold at the Old Arsenal Penitentiary in Washington D.C., and there they were hanged (via The Washington Post). All four were executed for their connection to assassin John Wilkes Booth, although their role in the plot to kill President Lincoln is still widely debated and even forgotten.

One of the four, Mary Surratt, was also the first woman ever executed by the American government, a move that proved to be highly controversial. At the time, even Surratt's own executioner was shocked at the order, and after her execution, many Americans expressed their unease about her death (via History).

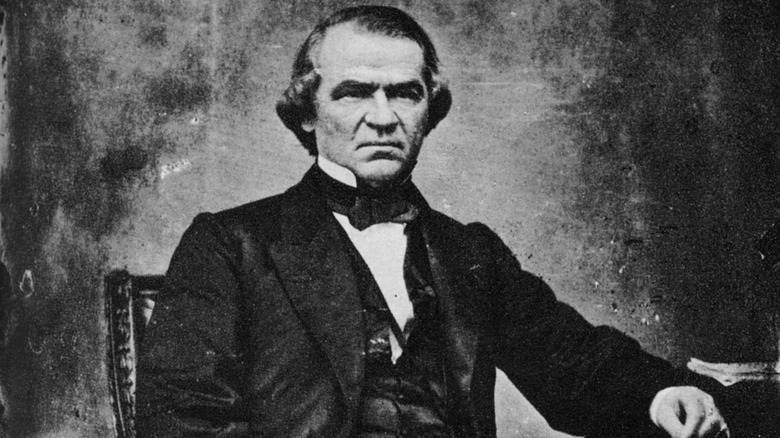

Pleas to commute her sentence to life in prison fell on deaf ears, waved away by President Andrew Johnson, who was content to let her hang. To this day Surratt's guilt has been called into question, partly because she swore she was innocent right up to the moment of her death.

Mary Surratt's notorious boarding house

How did Mary Surratt end up on the scaffold? Surratt was undoubtedly sympathetic to the Southern cause. She was once married to a secessionist tobacco farmer (via Time), but after she was widowed she rented out her Maryland farm and tavern and began running a boarding house in Washington D.C. to make ends meet (via History). The house was situated at a convenient spot for sending urgent communications, and pretty soon Confederate agents began showing up there — and Mary's son John was at the very center of the clandestine spiderweb that began to form around the Surratt boarding house.

While some historians have speculated that Mary may have been innocent, her son John Surratt was undeniably guilty. During the Civil War, John began mailing messages on behalf of the Confederate side (via Smithsonian Magazine), and he developed a number of ingenious methods for hiding secret mail. John heartily enjoyed his time as an agent, commenting after the war that "It was a fascinating life to me ... It seemed as if I could not do too much nor run too great a risk."

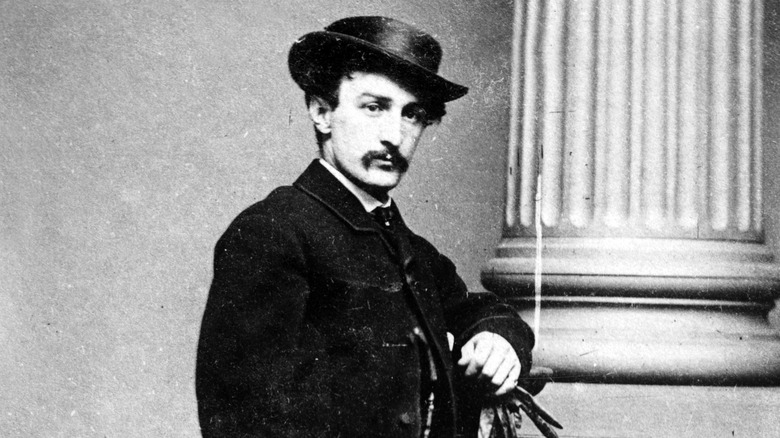

Through his secretive activities, John Surratt soon got to know John Wilkes Booth (above), who became a regular at the boarding house. Before long, John Surratt was personally involved in a plan to kidnap the president — a plot that would eventually turn into a murder. Although he admitted his involvement in the plot years after the assassination, unlike his mother, he would get off scot-free.

Arresting the wrong Surratt?

After the murder of Lincoln was carried out, Booth escaped the theater but was later gunned down while hiding out in a barn in Virginia (via Smithsonian Magazine). Investigators discovered the Surratt boarding house's role in the plot straight away, and after they caught one of the plotters there (Lewis Paine), Mary was arrested.

John Surratt, on the other hand — already a suspect for a different crime — had gotten the hell out of dodge. He would run and keep running — to Canada, to Rome, and even to Egypt. Although the authorities would catch up with him eventually, in the immediate aftermath of the murder Mary was the one left to endure the wrath of a country in mourning.

Although Mary protested that she knew nothing about what the men were actually up to, a tavern keeper who leased property from her claimed that she was directly involved, reporting that Mary had been asked him to prepare guns for Booth and another accomplice on the day of the murder (via The Washington Post).

The trial commences

To prevent any trouble, the conspirators were tried in a military court rather than by a normal jury, and there they were found guilty and sentenced to hang. Whether or not the tavern keeper's testimony proved her guilt, Mary's friendly connection to the conspirators certainly looked pretty suspicious. Booth and Mary had gotten on particularly well, and the two had sometimes hung out socially, independent of the others (via Time). Mary's fierce love for the South was also, perhaps unfairly, brought up in court (via History).

While some have claimed that the trial was a farce, and should not have been carried out by the military, according to historian Thomas Turner (via a 1982 article in the Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association), the court actually asked that Surratt be shown mercy — after all, no woman had ever been executed by the U.S. government before. Five of the nine commissioners recommended leniency (via Smithsonian Magazine). President Andrew Johnson (above), on the other hand, took a hard line on the issue, famously stating that Mary had "kept the nest that hatched the egg."

The execution

Some of Mary's supporters came forward to defend her at her trial, including several priests (via Time). Her most loyal defender, however, was her daughter, Anna, who stood outside the White House demanding to see the president on her mother's behalf — a request that was denied (via History).

Newspapers from the time reported that bystanders were "moved to tears" by Anna's pleas (via The Washington Post). It was later reported that President Johnson had been asked multiple times to save Mary because she was a woman and because of her age — she was in her 40s — something he could not allow because he believed it would set a bad precedent (via The Washington Post).

All hope lost, Mary was marched to the scaffold dressed in black. Before she dropped she is reported to have said, "Don't let me fall; hold on!" (via The New York Times). Mary's son John, nowhere to be seen, was described as a coward by a New York Times report on the execution.

Unhappy ghosts

After his mother's death, John Surratt (above) was dragged back to the states from Alexandria, Egypt, in 1867. However, he was acquitted after being tried by an ordinary jury, possibly because some of the jurors were from the South and were sympathetic toward John (via Smithsonian Magazine). Among historians, the jury is still out as to Mary's guilt (via History). Many think the hysteria surrounding Lincoln's death, the absence of her son, and the harsh decisions made by Andrew Johnson are to blame for her sentence.

Grant Hall, where Mary Surratt and the three other condemned prisoners were once housed, is believed by some to be haunted by Mary's unhappy ghost (via The Washington Post). Today sentencing women to death remains just as shocking as it was in the 19th century — only 3.6% of all confirmed executions carried out in the U.S. since 1632 have been women (via the Death Penalty Information Center).