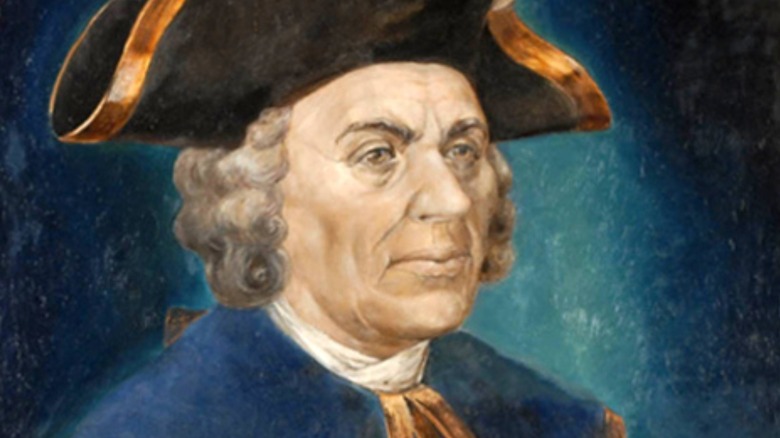

Who Is Vitus Bering, The Man Who The Bering Strait And Sea Are Named After?

Stranded on a small island off the coast of Alaska in the freezing depths of winter, the last days of explorer Vitus Bering's life were cruelly bleak (via National Geographic). Although Bering now gives his name to both a sea and an island, he would pay for that honor with his life, perishing under a foreign sky in an unknown land.

Bering led the longest and most ambitious scientific expedition in history (via New Scientist), the Great Northern Expedition — his last voyage a daring attempt to find a route between Russia and North America. Bering's crew accomplished many firsts — they were the first Europeans to set foot in Alaska and they recorded a host of information about native flora and fauna along the way. On the other hand, they were not actually the first European crew to cross the Bering Strait. That honor goes to a 17th-century Cossack, Seymon Dezhnev, who began his career as an explorer almost by accident, ordered to hunt down tax dodgers in the remotest parts of the Russian Empire (via Russia Beyond).

Today, a windswept lighthouse on Dezhnev Cape in eastern Russia commemorates the adventures of the hardy Cossack. However, during the 18th century, his exploits had faded from memory, and a new generation of explorers was called up to find a new way to the new world.

Growth of the Russia bear

Geographically, Russia today is the largest country on earth, containing 11 separate time zones and many ethnic groups and languages (via Russia Beyond), but the hulking Russian bear only expanded to its present size very slowly over hundreds of years.

During Dezhnev's lifetime, Russia made a concerted effort to control the ethnic groups who lived on the borders of the known world, the Eastern coast of Asia, and when Bering was alive in the early 1700s they were still fighting for control there (via Russia Beyond). The Kamchatka Peninsula, from which Bering would depart across the sea, was (and still is) a world of wild, dramatic landscapes, where arctic winds mingle with clouds of volcanic smoke, generated by numerous active volcanoes (via UNESCO).

This wild region still contained many mysteries, and at the time, it was believed that there might be a convenient land bridge connecting Asia to America (via National Geographic). In 1725, Peter the Great (above), perhaps the best-loved of Russia's sometimes tyrannical czars, gave the order to Bering to investigate.

Looking for Alaska

Bering, a Dane by birth, joined Peter the Great's newly modernized Russian navy in 1704 (via National Geographic), and he became part of Peter's push to explore Asia, charting the coasts of Siberia over a 10-year period (via Cambridge University).

Unfortunately, Bering's first attempt to find America, beginning in 1728, was a total disaster by nearly any measure. Many members of the expedition starved to death on the incredibly long march toward the coast, and although Bering successfully sailed across the strait, he never saw mainland America.

The distance between Russia and Alaska is only 55 miles at the narrowest point, but the group failed to find it after their ship got caught in thick sea fog (via National Geographic). While he didn't find the mainland the first time around, Bering did find Lawrence Island, which is more or less halfway there and still part of Alaska today.

The Great Northern Expedition

Bering returned to St. Petersburg but was soon sent off again, this time on a trip that was far grander, more exciting, and better recorded. The Great Northern Expedition was carried out by Empress Anna after the death of Peter the Great (via National Geographic).

Many scientists were called up from various parts of Europe for the venture (mostly from Germany), in order to fill in blank spaces on Russian maps (via the Library of Congress). This enormous undertaking had a huge impact on our knowledge of the natural world and has since been turned into an incredibly long series of tourist trails (via The Great Northern Expedition) in Russia.

One of the great scientists Bering took with him was zoological legend Georg Wilhelm Steller. Although the pair fell out during the trip, Steller managed to make great strides in his field, describing sea otters, sea birds, and the Steller's sea cow along the way. Most exciting for us, Steller also recorded Bering's trip in his diary.

Land ho!

Bering and his crew departed from Kamchatka in two boats, the St. Peter and the St. Paul, in the summer of 1741 (via National Geographic). They were not, however, blessed with blue summer skies, and a violent storm separated the ships while at sea.

Bering's ship, the St. Peter, pulled through the storm, and after spotting Mount Elias (above), they finally landed on Kayak Island, a stone's throw from mainland America. Having finally arrived, the group began to carry out their mission to study the land, and they immediately bumped into the indigenous groups who lived there while they did so (via The National Park Service). Predictably, Steller pocketed some of their stuff before he left, as well as samples of plants and seaweed. The crew would continue to explore Alaska during the next few weeks — before half the group began dying of scurvy.

The expedition's other ship, the St. Paul, also sighted Alaska. However, the crew chickened out and returned to Russia early, after the scouts they sent to explore the mainland vanished without a trace.

How Bering Island got its name

Unfortunately for Bering, he would never come home from his adventure. He and the rest of his crew had become gravely ill, and they decided to return to Russia. Upon departing the crew once again got trapped in a terrible arctic storm (via National Geographic), and this time their ship was smashed to splinters, leaving them stranded on a freezing, barren, and completely deserted island (via PBS), now known as Bering Island.

Bering died on December 19, 1741, and many members of his crew died as well. Incredibly, the survivors eventually managed to rebuild their boat and get back to Russia (via Smithsonian Magazine), almost a year after they'd originally left, in September 1742.

Russian Alaska went on to become home to a thriving fur trade. However, the difficulty of living in the frosty northern wilderness exasperated even the hardy Russians, who began looking for warmer lands further south. The Russians eventually gave up on Alaska altogether, selling it for a song to the U.S. in the mid-19th century.