The Dark Truth About Murderabilia

It's no secret that people are fascinated by true crime stories — especially when they star serial killers. There's a lot of darkness carried in the souls of the human race in general, and when it comes to serial killers, there's something about them that makes the rest of us want to understand just what drives a compulsion to kill, torture, and mutilate. Thanks to social media, documentaries, and Netflix, there are plenty of opportunities to get a true crime fix. But what happens when that's not enough? Enter: Murderabilia.

The term was coined by Andy Kahan, who has a slew of credentials — including (via the Office of the Texas Governor) involvement with the Harris Law Enforcement Advisory Council, Parents of Murdered Children, and Texas Equusearch, an appointment to the Crime Victims' Institute Advisory Council, and his role as the Director of Victim Services for Crime Stoppers Houston. Murderabilia, he says (via Katy Magazine), is a multi-million-dollar industry, and even if someone's pretty sure they know what it is, they're probably only scratching the surface.

In a nutshell, it's the sale of items related to murder and often, to serial killers. The more famous the killer, the higher the dollar value — and it's way darker than it sounds. According to Kahan, it's not harmless, either, and he says that it's once again the victims who suffer the most. As he explains: "The victims are the only people in the criminal justice system that are not there by choice."

What is murderabilia?

It's worth taking a look at exactly what "murderabilia" includes, because it's a massive industry that spans a huge number of items, and it gets really weird, really quickly. As a sweeping generalization, murderabilia is anything directly related to serial killers or murderers, and that's the only requirement. When Rolling Stone did their deep dive into how the industry started, they noted that there were a ton of items floating around out there along the lines of paintings and drawings (like those done by Richard Ramirez and John Wayne Gacy), letters, autographs, and clothes. That's a pretty standard sort of celebrity fare, but here's where things go off the deep end.

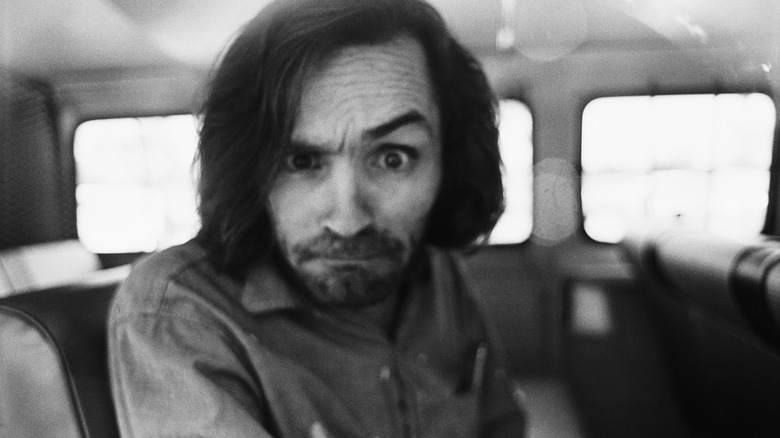

There's also a booming market for things like hair and fingernail clippings from serial killers, and used deodorant is a big one, too. The Huffington Post collected listings from some of the weirdest, and it turns out that anyone interested in getting up close and personal with a convicted killer can absolutely buy things like a bag of Reese's Pieces, half-eaten by Charles Manson, or a paper towel he (reportedly) handled. Not close enough? How about some skin scrapings off the feet of "Railway Killer" Angel Resendiz?

Kahan says (via Oxygen) that there are other, less directly related items that also fall under the label of murderabilia. Those are the collectibles and the merchandise, and there's tons of it that's incredibly questionable — like the Jeffrey Dahmer doll that can be unzipped to reveal the removable body parts of his cannibalized victims.

What is the psychology behind wanting to own a piece of murderabilia?

It's one thing to watch a documentary on a serial killer and want to understand the history of a crime, the consequences, and the outcome, but it's an entirely different thing to want to own the killer's fingernail clippings. What's the attraction?

Scott Bonn is a criminology professor with Drew University, and says (via Baruch College) that it has something to do with what's called the "talisman effect." That's when an item supposedly embodies some of the characteristics and essence of the person who once owned it. "It's a way to expose yourself to evil and danger without actually having to do it," he explained. "You're just collecting it or holding it as opposed to engaging or encountering with Jeffrey Dahmer or someone like that."

Experts at Psychology Today echo the idea that getting up-close-and-personal with serial killer merch causes a feeling of awe and a sense of getting close to violence and death, but also suggests that for some people, there might be more to it. Some, they say, hold a superstitious belief that there's something lucky about these items, and that they're able to keep the very harm and death they embody away from those who own them.

Victims' families have protested the commercialization of their loved ones' murders

The biggest condemnation of murderabilia has come from the families of victims. Stories are pretty heartbreaking, like the one of James Byrd Jr. ABC reports that John King — a vocal white supremacist — was convicted of killing Byrd by dragging him behind his truck for miles. King's photo showed up for sale on one murderabilia website, and Byrd's sister summed it up like this: "That's unbelievable, unacceptable to me. And as a victim of a hate crime, I think that we've been slapped in the face."

Theirs isn't the only story. Harriet Semander's daughter, Elena, was one of the victims of serial killer Coral Eugene Watts, and when she saw his letters being auctioned off, she said (via ABC), "It just brings all that pain back. And it's not gonna go away." Wendy Lavin had a similar experience. John Charles Eichinger confessed to killing her 20-year-old daughter, and when she came across his letters for sale — while she was looking for an update about his appeals process — she was horrified. "I was disgusted there was a market for anything attached to him," she told Today. "I felt sickened."

It was the impact of murderabilia on victims that motivated advocate Andy Kahan to take a stand against the industry, saying (via Oxygen): "I can tell you there's nothing more nauseating and disgusting than to find out the person who murdered your loved ones has items being hawked by third parties for pure profit. It's like being gutted all over again by our criminal justice system."

Fascination with murderabilia is nothing new

While the term "murderabilia" might be fairly new, our collective fascination with relics and items connected to killers goes back a long time.

Psychology Today says that preserving things like murder weapons, bones, letters, and autographs of convicted killers goes back to the 19th century. That's about the time when criminologists were starting to examine the psyches of people who couldn't go through life without killing, and after the Austrian criminologist Hans Gross started collecting items for his museum, enterprising entrepreneurs realized that people would pay to own some of these things. It's all about demand, and there was plenty of it.

And there has been for a long time. When Sarah Dazley was executed at Bedford Gaol in 1843, she was considered the U.K.'s first female serial killer — and according to the Bedford Independent, those attending the execution could purchase ornaments carved from bone to commemorate the momentous occasion. Long before that, it was the hangman's rope that was considered the most valuable artifact of an execution. According to Executing Magic in the Modern Era, it was widely believed that a hangman's rope could cure headaches. Pieces were one of the major components in magic spells cast for love; they were thought to be able to guide human emotions and feelings, along with being lucky charms that would aid a card-player or protect against injury. Selling pieces of a rope used to hang a criminal? That was big business.

The Son of Sam laws were an attempt to block the sale of murderabilia

If the sale of murderabilia sounds like something there should be a law against, there is ... technically. According to the Freedom Forum Institute, around 40 states have laws against the sale of murderabilia, but they're challenged as quickly as they're written. Why? Those who oppose the laws argue — often successfully — that they go against First Amendment rights of free speech.

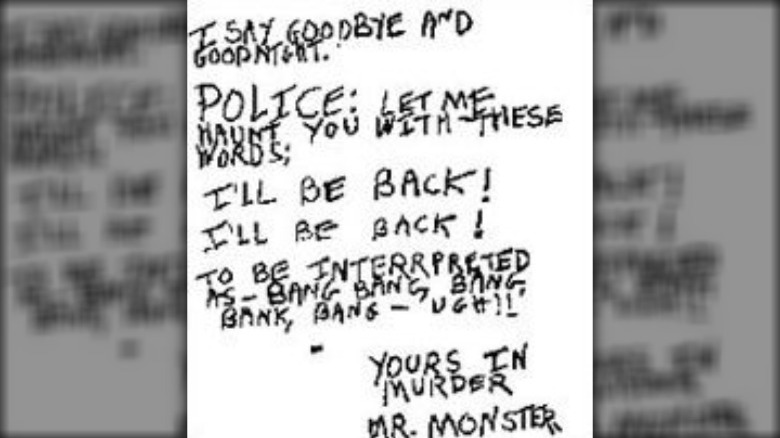

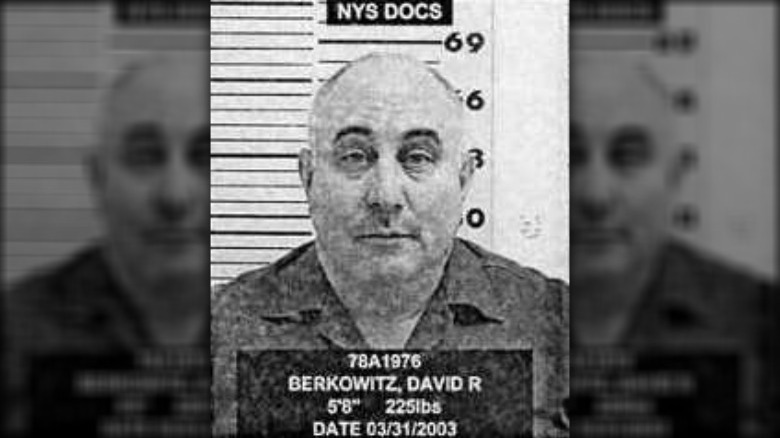

But let's go back to the 1970s, when the so-called Son of Sam was killing across New York City. After David Berkowitz was arrested, tried, and sentenced, he was offered a ton of money for his story, which led to questions about whether or not Berkowitz should be able to make money off his crimes. The initial response was to pass the first of the "Son of Sam" laws, which stated that proceeds needed to go to the victims or victims' families.

When the law was invoked over a book by mobster and FBI informant Henry Hill — which was later turned into "Goodfellas" — it went to the Supreme Court. They ruled that yes, it did violate freedom of speech, but at the same time, confirmed that victims had a right to compensation. That's made enforcing the laws pretty tricky, and it's left those who see items for sale from their loved ones' killers without much in the way of legal recourse.

The speed at which items go up for sale is ridiculous

In 2001, eBay took a stand against murderabilia by announcing that they were banning sales of anything connected to "notorious individuals who have committed murderous crimes within the last 100 years." That came on the heels of an announcement that Texas was planning on seizing the profits from these sales, and as reported by Chron, it was done "out of respect for the immediate family members of murder victims."

There are, however, plenty of other independently owned and operated websites out there that have stepped up to fill the void — although, as Today notes, many are pretty secretive about what goes on behind the scenes. Before the internet and online sales, murderabilia could be purchased via mail-order catalogues. Victim advocate Andy Kahan says magazines with names like Grindhouse Graphics hawked murderabilia throughout the 1990s. But the internet means that things go up for sale at a shocking rate of speed.

In 2005, Dennis Rader was arrested as the notorious serial killer BTK, and even more shocking than the unmasking of this seemingly ordinary, church-going family man? Within 48 hours of his arrest, the internet was flooded with sales of more than 400 items connected to him.

Who actually profits?

Congratulations! You've just spent hundreds of dollars on a tarot card said to be signed by Charles Manson himself. Who gets that money? It's complicated.

ABC News spoke with Todd Bohanon, who runs the site selling that tarot card. He said that not only does he personally feel that what he's doing isn't bad, but he also pointed out that it's legal — and he added that yes, sometimes he does send money back to the source. That said, he was also quick to say that they're not getting much: "They might be able to buy some M&Ms or some cigarettes, but none of them are bankrolling a weekly salary," he says.

Drew University criminology professor Scott Bonn says (via Baruch College) that the profits from the overwhelming majority of murderabilia sales go into the pockets of third-party vendors. Crusading against the industry on a platform of preventing serial killers from profiting from their notoriety and their crimes just doesn't really work, because they're not the ones making most of the money anyway — it's those selling the items who rake in the dough.

Keith Jesperson, the Happy Face Killer, has some strong feelings about why it's wrong

So, here's some food for thought: Even some serial killers think that the whole idea of murderabilia is wrong. Just let that sink in for a second.

Keith Jesperson surrendered to authorities in 1995. He was being investigated in connection with the murder of 41-year-old Julie Winningham, and after he gave himself up, he was connected to the murders of seven additional women. He described it (via ABC) as "like shoplifting. You're breaking the law, but you're getting away with it." In 2021 — while serving life in an Oregon prison — he spoke with The Crime Report on the subject of murderabilia. At the time, his artwork was one of the most in-demand items on the market, and he explained that while getting mail was nothing new, more and more were requesting things like fingernail clippings, artwork, and locks of his hair. "I feel like I'm being used, and I'm not really cool on that. I'm a commodity to them. I'm not something of value to them as a human being," he explained.

He's not the only one who's spoken out against it. One-time Manson family member Susan Atkins also explained the problem with murderabilia from her perspective, saying that not only did she never consent to sales, but, "This makes me look callous and unremorseful, for which I am not, and it leads to unscrupulous behavior by other inmates and prison guards that realize they can make money off me."

David Berkowitz is working to try to stop the sale of murderabilia

According to Today, many of the companies that deal in murderabilia don't publicize insider information on how the industry works. That's forced victim advocate Andy Kahan to get creative when it comes to learning the ins and outs of how items get from killer to market. After he started buying murderabilia to learn about the industry, he found an unlikely ally in his mission to get things off the market (via Oxygen).

Kahan says that when he started the project, he went to the sources: serial killers themselves. After sending out inquiring letters, he received 12 back — including one from David Berkowitz. More famously known as the Son of Sam, Berkowitz isn't just the inspiration for the failed laws against murderabilia. Kahan says that for more than 20 years, Berkowitz has been helping him learn how the trade works by sending him all the requests he gets for new murderabilia.

"So I get to see what everybody's up to," Kahan explained. "It doesn't get any better than having an inside source from whom all the profiting laws are named after."

Why? Kahan says Berkowitz's interests lie in preventing convicted killers from financially benefiting, and he adds that his motives — and remorse — strike him as genuine. In other words: If you buy murderabilia, the Son of Sam thinks you probably shouldn't be doing that sort of thing.

Can it feed the psyche of a convicted killer? Absolutely

Terms like "psychopath" get thrown around in discussions about serial killers all the time, but according to the FBI, it's not that straightforward. Not all psychopaths become serial killers, but many serial killers do possess psychopathic characteristics — "particularly their inherent narcissism, selfishness, and vanity." And here's where murderabilia comes in, because it can definitely help feed a serial killer's ego.

Keith Jesperson — the Happy Face Killer — talked to The Crime Report about how problematic he saw murderabilia as being. "Your value to [the buyer] is how bad of a person you were on the street, and how you were arrested and remembered," he said.

The more notorious the serial killer, the higher the price their merch will bring. Will that feed into their narcissism? Absolutely. Today spoke with Clint Van Zandt, a former FBI profiler and hostage negotiator. He said that while collecting or being fascinated by murderabilia didn't mean the collector had the potential to be dangerous, it did make it likely that it would give the killer a serious ego boost — whether they were getting the money or not. He explained: "What a serial killer wants to hear is, 'I'm so much smarter, so much more creative, even though society locked me away, people still desire a part of me.'" And murderabilia? It's giving them that.

Books and movies about serial killers come out all the time. Why is this worse?

So here's a legitimate question: There are scores of movies and television shows made about serial killers. From Dahmer to Bundy, most of the big names have had big names from the entertainment industry attached to telling their story. Robert Applewhite, the figure behind the site Cult Collectibles, told The Crime Report: "I don't see why someone would be fine with Netflix making money off a true crime case, but be mad that someone is selling a painting by that same criminal."

The response to that is twofold, and it starts with the fact that people aren't unanimously fine with Netflix making money off serial killers, as illustrated by the massive outcry against the fictionalized version of events told in "Monster: The Jeffrey Dahmer Story." That series, says The Conversation, got some major criticism for — among other things — insensitivity and traumatizing victims all over again. And that's kind of similar to the protests against murderabilia.

That said, those dramatizations have something that murderabilia doesn't. Victim advocate Andy Kahan explains: "[In dramatizations] you also include the victims. ... if you're going to write a book, you also have to include why we're writing this book and [who] lost their lives as a result of this person. ... John Wayne Gacy, Richard Ramirez, Ted Bundy, Jeffrey Dahmer, David Berkowitz — we all know. Can you name any of their victims? Nobody can ... unless you're really, truly immersed in this." Bottom line? Murderabilia doesn't just traumatize victims' families — it ignores them.