How This Fossil May Have Changed The Way We Think About Beavers

Beavers are extremely important for healthy river environments. These semi-aquatic rodents are called "ecosystem engineers" because of their dam-building abilities, according to Sierra Magazine. Beavers build dams to create a beaver lodge for themselves where they can be safe from predators, according to the National Park Service. However, their ponds have the side benefit of creating wetland homes for animals, from salmon to boreal toads to wood ducks to moose, filtering water pollution and reducing flood risk, according to Sierra Magazine.

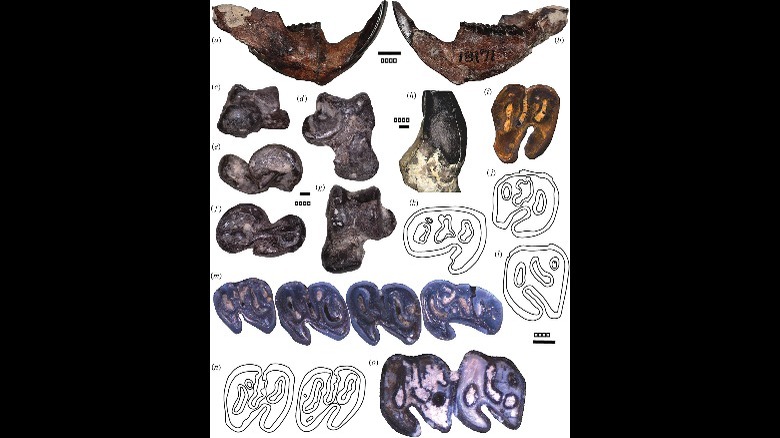

Now, a new study published in the Royal Society Open Science on August 24 tells us more about how these toothy builders came to be. In the study, scientist Jonathan J. M. Calede of The Ohio State University described the fossil that he said belonged to the oldest amphibious beaver known to have existed, at around 29.92 million years old. That's remarkable for two reasons: It pushes beaver evolution back by around seven million years, and it means the first known beaver is now linked to North America, not Europe or Asia. "The oldest semi-aquatic beaver we knew of in North America before this was 17 or 18 million years old," he told Ohio State News. "And the oldest aquatic beaver in the world, before this one, was from France and is about 23 million years old."

Microtheriomys articulaquaticus

Jonathan J. M. Calede and a team of scientists found the ancient beaver fossil in Montana, and knew right away it belonged to a beaver because of its teeth, according to Ohio State News. They named the new species Microtheriomys articulaquaticus, according to the Royal Society Open Science. The age of the fossil means this beaver was active during the Oligocene Epoch, which lasted from between 33.9 to 23 million years ago, according to the University of California, Berkeley. This was the epoch in which some of today's most beloved mammals, like tusked elephants and early horses, appeared. And now, it turns out, beavers.

Microtheriomys articulaquaticus was different from today's beavers in many ways. In fact, it lacked two of the current beaver's most defining attributes, according to Ohio State News. It didn't have a flat tail, and it probably didn't eat wood, preferring plants instead. Further, it was much smaller, weighing less than two pounds instead of around 50. This isn't unexpected, however. There's actually a scientific concept known as Cope's Rule, according to which animals become larger over time as they branch up an evolutionary tree. Calede looked at beaver evolution and found that this held true.

Around 12,000 years ago there was a giant beaver in North America the size of a black bear. This now-extinct behemoth, scientific name Castoroides ohioensis, could grow to be as tall as 7.2 feet and as heavy as 275 pounds, according to the Illinois State Museum.

It's all in the ankle bone

Jonathan J. M. Calede wasn't only able to identify a new and older species of beaver. He was also able to develop a new hypothesis about how beavers evolved. This was all down to the species' ankle bone, according to Ohio State News. The ankle bone was only around 10 millimeters in length, but Calede was able to mine a wealth of data from it by comparing it to more than 5,100 ankle bones from 343 species of living rodents as well as ancient beavers. This led him to the conclusion that beavers evolved to be aquatic from something called exaptation. This is when an animal uses a trait evolved for one purpose to perform another one. In this case, Calede said, "Beavers went from digging burrows to swimming in water." That's because the two skills use similar movements that are made easier by similar anatomical traits.

While Microtheriomys articulaquaticus is an important piece in the puzzle of beaver adaptation, it might not actually be the first piece evolution put down. "I'm not claiming this new species is necessarily the oldest aquatic beaver ever, because there are other animals that we know, from their teeth, that are related to this species I described," Calede said. However, fans of beavers today can be grateful this ancient rodent made the move from the earth to the stream.