How Helpful Are Police Sketches In Solving Crimes?

After a major crime, we've all seen police sketches on the news, in the newspapers, and on social media, along with a request for help from the community in identifying the suspect. Sometimes they're so rudimentary or so nondescript that they look like everybody and not nobody all at the same time. Others can be so highly detailed that a police officer could spot the suspect a mile away. All of it is in the hands of a forensic sketch artist and the description the artist can extract from a victim of — or a witness to — a crime.

The history of modern police sketches has been traced to Alphonse Bertillon, a 19th-century French police officer and biometrics researcher, who applied anthropological techniques to law enforcement. According to the National Library of Medicine, Bertillon began cataloging the physical characteristics of criminals in Paris. He would take the lengths of their arms, calculate their height, note their scars and tattoos, and measure the circumference of their heads, among other things. When possible, he'd photograph their faces and their profiles, leading to the modern-day mugshot.

And when photography wasn't available, he would arrange for a sketch. In 1884 alone, police in Paris used his methods and sketches to catch 241 repeat offenders. Soon after, law enforcement throughout Europe and the U.S. adopted his methods. So, if police sketches are still being used more than a century later, that must mean they work, right? As you might imagine, it's more complicated than that.

Police sketch success statistics aren't great

Statistics on the effectiveness of police sketches tend to be, well, a bit sketchy. According to one study (via The Washington Post), people were asked whether they believed a sketch accurately reflected a corresponding photo of an individual. Only 30% of the respondents said they did. Just one problem: All of the sketches were meant to reflect the photo. And according to HowStuffWorks, less than 10% of police sketches produce a likeness to an actual suspect. Per the Houston Chronicle, the most optimistic statistic is that about 30% of sketches lead to an arrest.

That gap has little to do with the skill level of the artist and more to do with the witness. The sketch artist must be able to connect with the victim or witness at a time of high stress. They have to find a way to calm them down enough for an informative interview and then interpret the descriptions they can offer at the time.

Witness testimony is notoriously unreliable, so even if the witness is able to communicate effectively, did they remember the events and the suspects accurately? One study (published in Scientific American) found that 75% of wrongful convictions were based on witness accounts, per Science. According to the study, errors often creep in when witnesses who are eager to help believe they have seen details that they have not, which can lead to inaccurate witness accounts, including poor sketches.

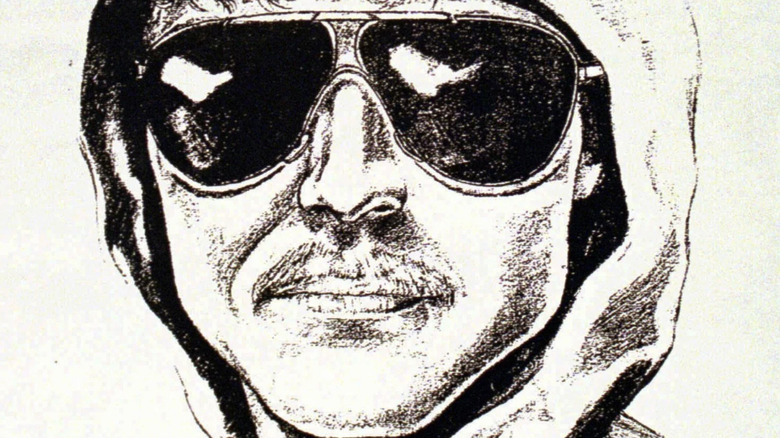

Even inaccurate sketches can lead to arrests

Lois Gibson (pictured above), a forensic sketch artist who spent decades working for the Houston Police Department, holds the Guinness World Record for "The World's Most Successful Forensic Artist." By her estimation, she's helped officers arrest more than 1,000 criminals, per the BBC. That must mean she nails the overwhelming majority of her suspect sketches, right? Not so, says Gibson. "This is the only art I know of that you can do it pretty bad, goofy sloppy, but if it catches the person, it becomes perfect," Gibson told the Houston Chronicle. "Law enforcement thinks the drawings have to be perfect. They're wrong," she said, adding, "I have drawings in my sketchbook that are embarrassing, but they still caught the person immediately."

However, some law enforcement officers point out that expecting a sketch to directly lead to the arrest of a suspect is too much to ask. "The real goal is to generate investigative leads that investigators can pursue," according to George Babnick, a retired captain of the Portland, Oregon Police Bureau (via LinkedIn). Sketches are most often released when law enforcement is frustrated and they have few leads. The hope is that when the picture is released — even when it's comically bad — it will stir up conversation among the public and lead to a tip. Babnick added, "Sometimes a seemingly unimportant tip leads to the arrest of a perpetrator who otherwise would not likely be apprehended."