Why The US-Mexico Border Is Where It Is

For just over 200 years, the U.S. has had a complex, sometimes contentious relationship with Mexico, its neighbor to the south. Today, Mexico is the second largest trading partner of the U.S., with America trading over $700 billion worth of goods and services annually, supporting over 1 million jobs south of the Rio Grande (via U.S. State Department). The border between the two countries is relatively tranquil, with dozens of active border crossings dotted along the 2,000-mile stretch. It's also one of the busiest borders in the world, with hundreds of millions of people crossing it every year, the majority between Tijuana and San Diego (via Mexperience).

The border between the U.S. and Mexico has been fixed in its current location for over 150 years, so it's easy to forget that not only was the border radically different in the past, but at times, no one really knew where it was. To get a handle on the history and origins of the U.S.-Mexican border, we need to go back to before either the U.S. or Mexico existed.

Frontiers in colonial America

After the discovery of the New World in 1492, the great powers of Europe rushed to establish colonies and begin the process of extracting wealth from the Americas. Over 250 years later, European power in North America was divided between France, Spain, and the United Kingdom. Competing claims between France and the U.K. led to the outbreak of the Seven Years' War. The 1763 Treaty of Paris that ended the clash led to some of the earliest firmly established international boundaries in the Americas (via History).

Following the terms of the treaty, the French were expelled from the continent. Their resentment over losing their territory led to them tipping the balance in the uprising that led to the formation of the United States. The 1783 Treaty of Paris set the first internationally recognized borders of the nascent United States: all of the land south of Canada, north of Florida, and east of the Mississippi River (per National Geographic). While the American Revolution was getting underway, the Spanish were pushing their claims up the Pacific coast as far north as Sitka, Alaska, although in truth, this was land largely controlled by native populations. Inland, Spain controlled all of the Mississippi watershed west of the river on paper but had little physical presence there.

Adams-Onís Treaty

In 1799, something happened in Europe that would reverberate through history to the present day and have a profound effect on the American colonies: Napoleon Bonaparte took power in France. One year later, Spain returned Louisiana to France, which then sold it to the U.S. two years later. This set off negotiations between the U.S. and Spain to determine where their new border was. Those negotiations were put on hold, however, because Napoleon invaded Spain five years later, igniting chaos throughout Spain and Latin America (via Constituting America).

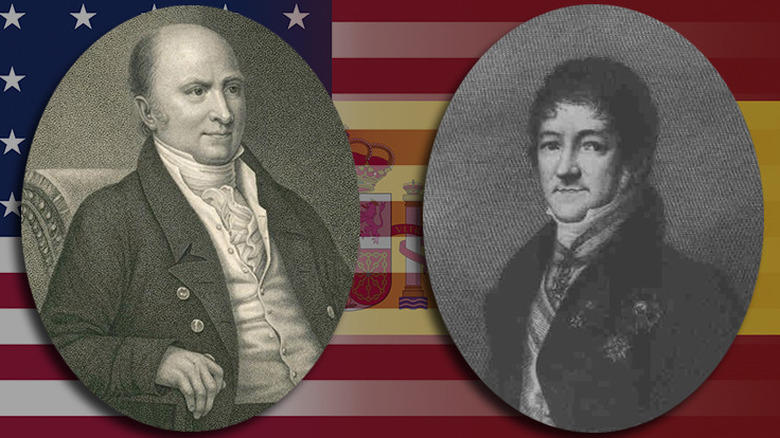

Despite the restoration of the monarchy and the downfall of Napoleon, Spain's grip on the Americas was tenuous at best. Most of its colonies were in active rebellion, and the United States was on the verge of taking Florida by force. Against this backdrop, secretary of state and future president John Quincy Adams and Spanish diplomat Juan de Onís negotiated the border between Nueva España's northern frontier and the recently purchased Louisiana Territory of the U.S. in 1818.

So what was the new border? It ran along the modern border between Louisiana and Texas, up to and along the Texas border with Oklahoma, north through the panhandle all the way to Dodge City, Kansas. From there, it followed the Arkansas River into Colorado, and from its headwaters, north to the 42nd parallel (the northern borders of California, Nevada, and Utah), and from there to the Pacific (via Yale Law School).

The Mexican-American War

One of the key points of the Adams-Onís Treaty was that in exchange for Florida, the U.S. would recognize Spain's sovereignty over Texas. Mexico won its independence in 1821 and eventually agreed to the borders in the 1832 Treaty of Limits, but only four years later, Texas won its independence (per America's Best History). Although Texas sought admission to the Union, the U.S. initially refused due to Mexico's threat of war if they did annex the fledgling republic. But by 1845, the U.S. was gripped by the fever of Manifest Destiny, and Texas was admitted as the 28th state (via History).

No one was more hungry for expansion than President James K. Polk. Initially, Polk tried to buy land from Mexico, but when he was rebuffed, he sent future president Zachary Tyler to provoke the Mexicans to attack American troops. By 1846, American blood had been spilled, and Congress was quick to declare war (via National Park Service).

The war was quick and brutal — the U.S. captured all the land between Texas and California and captured Mexico City in the fall of 1847. By the following year, Mexico signed away over 500,000 square miles of territory to the U.S. (via Britannica).

Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo

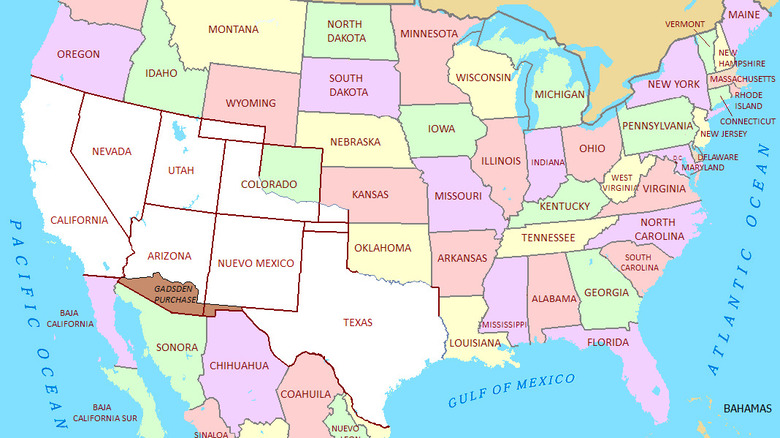

The new border now ran along the Rio Grande until it reached the southern border of New Mexico just north of El Paso. From there it ran west until it ran into the Gila River, which flows just south of Phoenix, and from thence to the southern border of California, then to the Pacific (via National Archives).

Its hunger not yet sated, the U.S. began negotiating the purchase of the Mesilla Valley in southern Arizona and New Mexico in the 1850s. There was a desire to build a southern railroad to the Pacific, and the land along the existing border was too mountainous. James Gadsden was sent to Mexico to negotiate for the purchase of the needed land. Although the U.S. intended to purchase a much larger piece of Mexico for $50 million dollars (Baja California and most of northern Mexico), they settled for extending the border to its present state for $10 million in 1854 (via U.S. State Department).

Territorial expansion came at a cost, however. The rapid addition of so much land in 50 years brought the issue of slavery to a head. There was acrimonious debate about whether the new territory would be free states (from U.S. History Scene), which led directly to the Civil War, the generals of which were forged in the battles of the Mexican-American War 10 years earlier.

New American empire

Even though the southern border of the U.S. was now firmly established (as was the northern border), the country continued to grow. A number of Pacific and Caribbean islands were acquired under the Guano Islands Act in the second half of the 19th century. Shortly after the Civil War, Alaska (all 580,000 square miles of it) was purchased from Russia for the paltry sum of $7.2 million (per Britannica). Toward the end of the 19th century, the U.S. acquired the island territory of Hawaii in 1898 (via the U.S. Department of State), followed by the Philippines, Guam, and Puerto Rico after claiming victory in the Spanish-American War (per Library of Congress). In 1903, after engineering Panama's secession from Colombia, the U.S. also took possession of the Panama Canal Zone (via History).

Following World War II, the U.S. granted independence to the Philippines and shifted its ambitions from territorial expansion to preventing the expansion of Communism via the Truman Doctrine. Instead of seeking new land, it sought new partners in an emerging international order it was forging — an order that continues to persist today (via The National WWII Museum).