The Worst Crimes Committed By The KKK

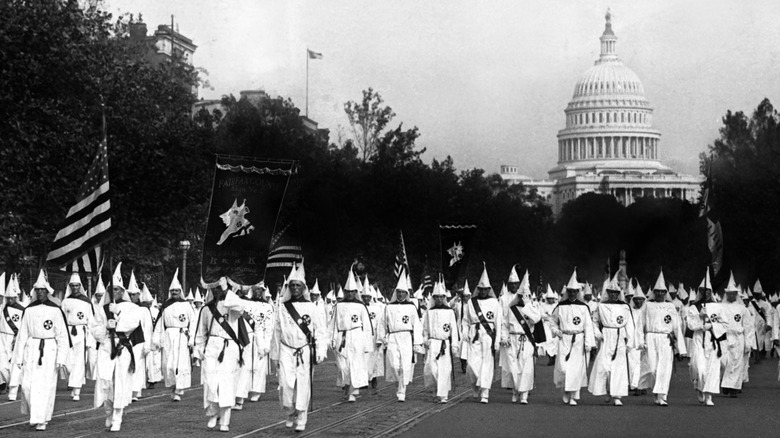

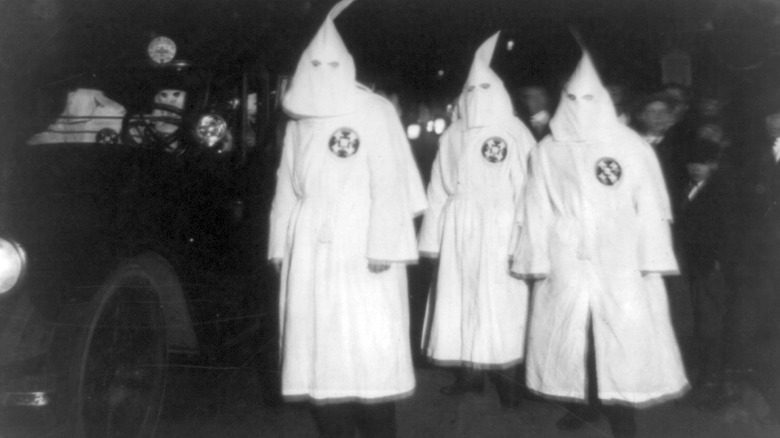

Let's say this upfront: Picking out the "worst" crimes committed in the history of the Ku Klux Klan is difficult because literally everything they do, say, promote, and stand for is the worst kind of awful. The KKK was founded in 1865 in Pulaski, Tennessee. It started out as a secret society promoting white racial superiority and the idea that post-Civil War America should look pretty much the same as pre-Civil War America. The ideas of the KKK took off because there were lots of people who wanted nothing more than to judge others based on the color of their skin.

The KKK so quickly became such a far-right, ultra-violent organization that, according to History, founder Nathan Bedford Forrest tried to stop the entire thing because it was too violent. Let that sink in for a minute: Within four years of its founding, the KKK had become too violent for the tastes of the founder and first grand wizard. By 1871, the U.S. government had authorized the use of force to put a stop to the widespread instances of domestic terrorism, and although activity receded in the 1880s, it resurfaced in the 1910s ... like warts on the feet of America, they keep coming back.

If you or a loved one has experienced a hate crime, contact the VictimConnect Hotline by phone at 1-855-4-VICTIM or by chat for more information or assistance in locating services to help. If you or a loved one are in immediate danger, call 911.

The attacks on the Freedom Riders

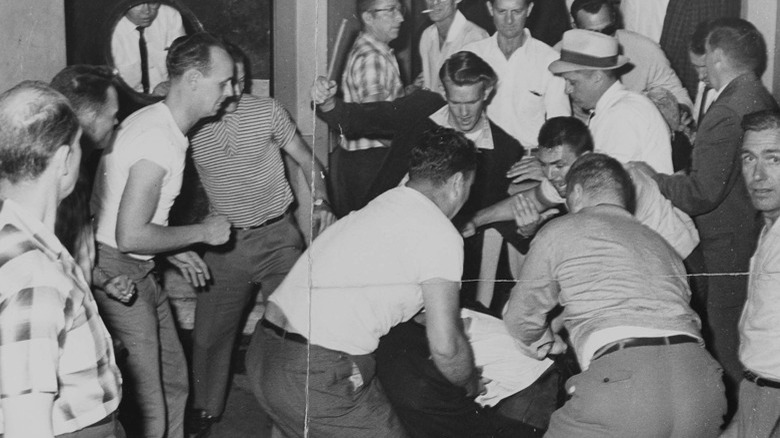

By the time the Freedom Riders embarked on their campaign to desegregate America's buses, a full century had passed since the Civil War ... and that puts things into a terrible perspective. Opposed by white Southerners led and backed by the KKK, the Freedom Riders faced some shockingly violent opposition like that which broke out on May 14, 1961.

That, says the Equal Justice Initiative, is when law enforcement was tipped off that the local branch of the KKK — led by a man named William Chapel — was going to attack a group of Freedom Riders at the bus stop in Anniston, Alabama. The group was headed to New Orleans from South Carolina when a mob of 50 or so armed men attacked the bus.

By the time police bothered to show up, it had already been damaged. Law enforcement escorted them out of town and abandoned them, which is when the mob returned to light the bus on fire and — when attempts at trapping the passengers inside the burning bus failed — settled for beating those who escaped.

Attacks continued: Two days later, another attack happened in Birmingham, and four days after that, there was another in Montgomery. Even though the federal government stepped in with promises of protection, state and local law enforcement did the opposite, and continued to promise the KKK that they would be allowed to continue without having to worry about police interfering.

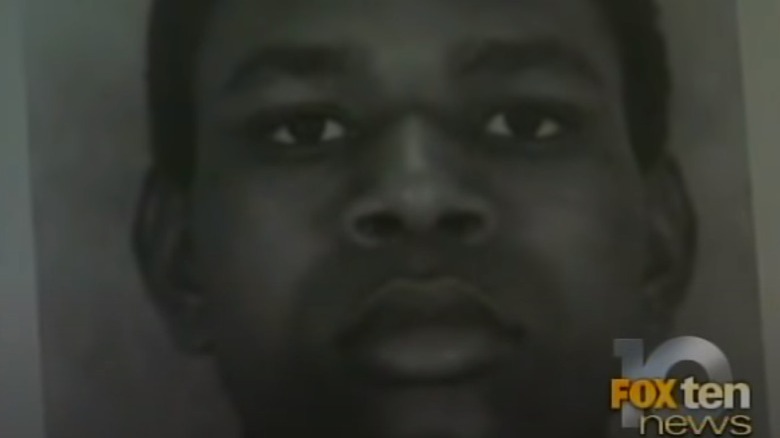

The murder of Michael Donald

The story of Michael Donald doesn't have a happy ending, but it does have a satisfying one, thanks to the efforts of his mother. It starts on the evening of March 21, 1981, and no, that's not a typo: This really, truly happened in the same week that REO Speedwagon's "Keep On Loving You" sat at the top spot on the Billboard charts.

It also starts, says History, with the KKK burning a cross in front of the courthouse in Mobile County, Alabama. Deciding that the night wouldn't be complete without an old-fashioned lynching, the mob started looking for their victim. They found it in 19-year-old Michael Donald, a local teen that ABC News describes as being a kind, quiet, responsible soul who often babysat neighborhood kids. He had been walking to a nearby corner store when he was abducted by the men he stopped to help with directions: He was beaten, hanged, and his body was discovered the next morning.

On the 28, they buried Donald after an open-casket funeral that his mother insisted on. She wanted everyone to know what happened: "The undertaker didn't want me to see where they'd made a footprint on his face with their boots."

It wasn't until 1984 that Henry Hays and James Knowles were found guilty, with the former getting the death penalty. Donald's mother, though, wasn't satisfied and went after the local branch of the KKK with a civil lawsuit. She was awarded $7 million, and successfully bankrupted the United Klans of America. Hays was executed in 1997.

The 16th St. Baptist Church bombing

Denise McNair was 11 years old. The others — Addie Mae Collins, Cynthia Wesley, and Carole Robertson — were just 14 years old when they were killed by a bomb set and detonated by Birmingham, Alabama's KKK.

It was Sept. 15, 1963, when NPR says the four girls had been standing in the 16th Street Baptist Church, not far from the stairwell where the KKK had planted the bomb. Sunday School was over, and they were waiting for church services — and a sermon that was supposed to be entitled "A Love That Forgives" — when the explosion happened.

Historians at Ferris State University say that the church had been targeted because of their congregation's involvement in the civil rights movement, and ultimately, the terrorist act did the opposite of what they'd hoped. The incident — which injured 22 others, including more children — galvanized the nation's support of civil rights legislation.

Are there more terrible footnotes? Of course there are. In the aftermath of the explosion, not only did no city officials attend the girls' funerals — which attracted thousands of mourners — but 23 Black citizens were arrested for a myriad of "crimes," and one young man was shot by police. Who wasn't arrested? The four KKK members who planted the 19 sticks of dynamite. They weren't charged for 45 years, and one died before those charges were brought.

The Greensboro Massacre

It's no secret that the word "Communism" has historically been a pretty bad word in the U.S., but on one autumn day in 1979, it was members of the Communist Workers Party that took on the KKK in a march and rally ironically named "Death to the Klan." It wasn't KKK members that would die that day.

History says that it was on November 3 that the Communist Workers Party of Greensboro, North Carolina, marched alongside local mill workers to protest the presence of the KKK. The Klan answered: An effigy of a Klansman was being dragged through the streets when seven cars — carrying around 30 KKK members and an Imperial Wizard — showed up. It took just 88 seconds for the two sides to exchange fire, and when the smoke cleared, five people were dead and another 10 were injured.

Politico says that this conflict is what set the stage for white nationalism in the 21st century, but, back to Greensboro, because there were some shocking details exposed in the aftermath. An investigation revealed that even though undercover informants had warned law enforcement that things were going to kick off in a big way, no one really bothered to do much in the way of stepping up. And? Some of the guns used in a massacre had been supplied by undercover ATF agent Bernard Butkovich.

Six defendants were initially acquitted. They were later found guilty in a wrongful death suit, and although the jury awarded around $400,000 in damages, they also ruled that there was no conspiracy.

The murders of Harry and Harriette Moore

According to the Smithsonian, the murders of husband-and-wife Harry and Harriette Moore made them the first to be martyred during the civil rights movement. It was Christmas night in 1951, and the explosion that tore through their Mims, Florida home was so violent that it was heard from miles away. It didn't, however, kill either Harry or Harriette — who, incidentally, had just retired for the night after celebrating their 25th wedding anniversary. However, there were no emergency services willing to take a Black couple to a hospital, so it fell to a few local relatives to drive them the 30 miles to the nearest hospital. Harry passed away not long afterward, and Harriette succumbed to her injuries the day after her husband's funeral.

It was no secret that the Moores had earned the ire of the KKK, for their work campaigning to end lynchings and protect Black voters. It didn't go unnoticed, but in spite of commitments from J. Edgar Hoover and the FBI, the case remains officially unsolved.

There is, however, a big "but." The FBI identified three Klansmen as being involved — one committed suicide, and the two others died of natural causes before the FBI could solidify their case. A 1978 deathbed confession reportedly confirmed that the man who had committed suicide had been the one to plant the dynamite, but History says no one was ever prosecuted.

September 1868

The post-Civil War south was a dangerous place to be, and in 1868, 18-year-old Emerson Bentley learned first-hand just how bad things were when he headed down from the north to work as a teacher to newly emancipated Black schoolchildren.

The first warning note was tacked onto the door of his schoolhouse in September, and conveniently signed by the KKK who had been harassing, stalking, and murdering indiscriminately for months. According to the Smithsonian, they were only one of a number of white supremacist groups in Louisiana, and they were all universally angered by Bentley's honest reporting in his other job, as an editor of a paper called The St. Landry Progress.

It was an editorial that ran on Sept. 28, 1868, that was ultimately the spark that kicked off two weeks of bloodshed that left around 250 people dead. The editor of another local paper would write, "The people generally are well satisfied with the result of the St. Landry riot, only they regret that the Carpet-Baggers escaped." The article then went on to declare that the dead and injured were "the upshot of the business."

Now called the Opelousas massacre, historians say it was this event that legitimized violence and lynching in Louisiana. Historian Michael Pfeifer as "an important precedent for the subsequent wave of lynchings that occurred in Louisiana from the 1890s through the early decades of the twentieth century."

The 1922 attack on Inglewood immigrants

Do a deep dive into the cesspool that is the KKK, and it quickly becomes obvious that there are a ton of groups that they hate — including immigrants and bootleggers. And that came into play in a shocking way in 1922, far away from the Klan's most famous stomping grounds in the deep south.

On April 22, around 100 klansmen broke into the Inglewood, California home of a family of Basque immigrants. According to the Los Angeles Times, Fidel Elduayer and his brother, Mathias, were beaten, while the daughters of Fidel and his wife, Angela, were forced to strip. (And that's where the records of their ordeal end.) Law enforcement showed up on the scene, and when the confrontation was over, one of the KKK's own was dead.

In spite of local KKK members testifying that they had only been trying to discourage some local bootleggers from plying their trade, an investigation was launched. The group was also linked to a series of incidents throughout the area, including other assaults, lynchings, tar-and-featherings, and targeted attacks on a nearby Japanese family who had been forced to flee their home with their children. Among the literal card-carrying KKK members connected to the crimes? The area's sheriff, and police chief.

Although 35 klansmen were indicted, there were no convictions. Buoyed by the appointment of a KKK member to the Los Angeles City Council, attacks continued.

The murder of Willie Edwards Jr.

When Willie Edwards Jr. vanished on Jan. 22, 1957, he left behind a wife, two daughters, and his job as a truck driver. For three months, it seemed as though he had just vanished into thin air, walking away from his truck mid-shift. Then, three months and a day later, his body was pulled from the Alabama River.

And then, years passed.

According to PBS, it wasn't until the very last day of 1975 that a man being questioned about a completely unrelated crime told law enforcement that he had seen a group of people forcing Edwards to jump from the Tyler-Goodwyn Bridge. Three members of the KKK were arrested, and while it seemed like Edwards's family might have been witness to justice finally being served, Henry Alexander, Raymond Britt, Sonny Livingston, and Jimmy York were all released when the case was dismissed. Why? There was no official cause of death.

Fast forward again, to 1993. That, says The New York Times, is when Diane Alexander — the widow of Henry Alexander — came forward to say that her husband had confessed to her that he had been a part of the group that had held Edwards at gunpoint, and told him to "Hit the water."

Alexander reached out to Edwards's widow, but it wasn't until 1997 that his body was exhumed and the cause of death was confirmed. Edwards had drowned, but with all but one of the men — Livingstone — dead and the statute of limitations up, the case was closed in 2013. No one was prosecuted, and Livingstone died three years later.

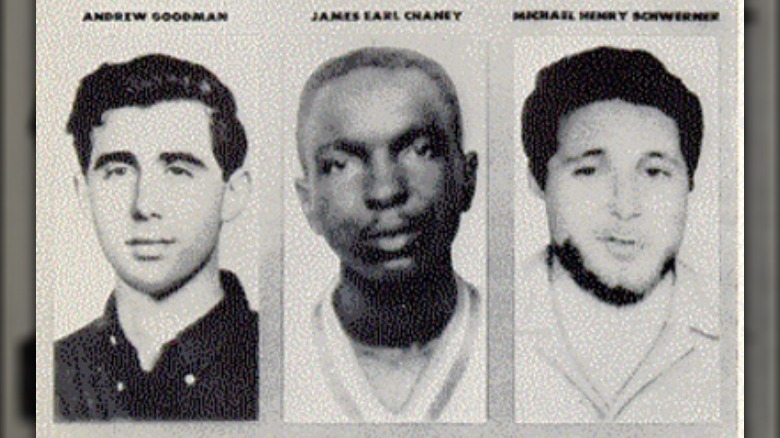

The Mississippi Burning murders

Made famous by the movie named after the FBI's code name for the killings — MIBURN, or Mississippi Burning — the murders of Michael Schwerner, Andrew Goodman, and James Chaney are perhaps the most notorious of KKK crimes.

It started, says History, with Schwerner's success in not only helping Black voters to register, but in boycotting a Meridian, Mississippi business. That alone was enough to get not just the ire of the KKK, but an official death warrant. The KKK's first target was Mt. Zion Methodist Church, and when he wasn't there, KKK thugs assaulted those who were, then burned the church.

Schwerner was out of town at the time, and when he returned — with Chaney and Goodman — the three were arrested in connection with the church fire. Hours later, they were escorted out of town and left, where they were quickly attacked by the KKK who had been looking for them. They were shot, killed, and buried in a shallow grave, discovered several weeks later amid a massive FBI investigation.

It wasn't until 1967 that seven members of the KKK were found guilty of the 1964 murders, and when it came time for sentencing, the longest jail term handed out was six years. U.S. District Judge William Cox later explained, "They killed one [expletive], one Jew, and a white man. I gave them what I thought they deserved."

The murder of Vernon Dahmer

In 1964, registering to vote wasn't easy — at least, not for Black Americans. There were plenty of registrars standing in the way of registering, and in Hattiesburg, Mississippi, that registrar was named Theron Lynd.

Fortunately, he didn't stand unopposed. Also living in Hattiesburg was Vernon Ferdinand Dahmer, who was well-known as a civil rights activist, businessman, and community heavyweight. The president of the city's chapter of the NAACP, he spearheaded a massive voter registration campaign, and when he publicly announced that he was going to pay the poll taxes for anyone who couldn't afford them, Civil Rights Teachings says that's when KKK leader Sam Bowers ordered his assassination.

Dahmer also worked closely with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, who says that it was the day after the announcement was made — Jan. 10, 1966 — that the KKK firebombed his house. After making sure his wife and their children made it out of the back of the house, Dahmer returned to his burning home to fire at the assailants, who had continued to hurl Molotov cocktails and gunfire.

Even as the Hattiesburg community gathered in support of Dahmer's widow and his family, the FBI ultimately charged 14 members of the KKK with murder. Three were convicted, but Bowers walked free... until the case was reopened in 1991, and ended with a conviction seven years later. He died in prison in 2006 (via SPLC).

The rape, torture, and murder of Madge Oberholtzer

Many times, those in power don't get their hands dirty — they leave that sort of thing to others. According to the Smithsonian, though, KKK Grand Dragon D.C. Stephenson didn't just get his hands dirty, he got them bloody. By 1922, Stephenson was not only in the Klan but well-known in his Indiana political circles for everything from indecent exposure and public intoxication to domestic violence and sexual assault. (One woman he assaulted was told, "Don't pay any attention to him; he is a good fellow; he is drunk, he is all right when he is sober.")

He met Madge Oberholtzer in January 1925, they quickly became an item, and on April 14, she was dead. The official cause of death was mercury poisoning, but that was only part of the story. Stephenson was charged with a slew of crimes, including rape and second-degree murder, after Oberholtzer's deathbed confession. She recounted (via the IndyStar): "He chewed me all over my body, bit my neck and face, chewing my tongue ... and mutilated me all over my body." Her first instinct had been to kill him, but not wanting her family to suffer through the indignities that would bring, she opted to die by suicide.

Stephenson was convicted, paroled in 1950, married several more times, and died after having a heart attack in 1966.

If you or anyone you know has been a victim of sexual assault, help is available. Visit the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network website or contact RAINN's National Helpline at 1-800-656-HOPE (4673).

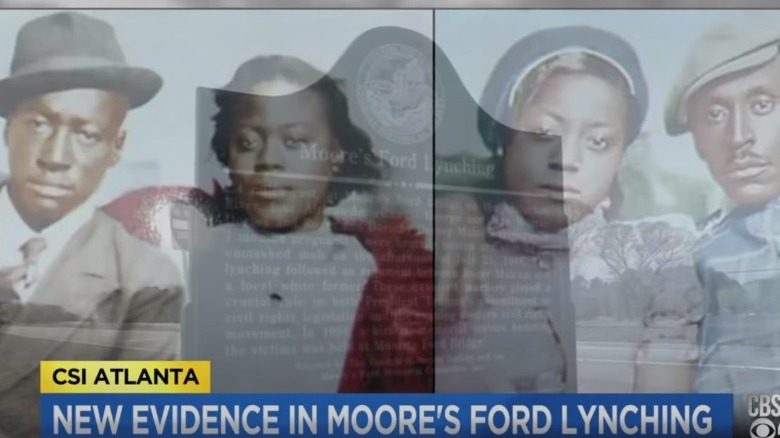

The Moore's Ford Bridge lynching

On July 25, 1946, at least four people — two couples — were killed at the Moore's Ford Bridge in Georgia. At least? Yes: According to The Guardian, the victims were George and Mae Murray Dorsey, Dorothy and Roger Malcom, and according to unconfirmed claims, the fifth victim was the baby cut from the very pregnant body of Dorothy Malcom.

According to CBS News, the four were given a ride by a local named Loy Harrison. Harrison happened to be a member of the KKK, so when he found the road blocked by more klansmen, what happened next perhaps wasn't surprising, but no less horrifying. The four were dragged from the truck, tied to trees, shot point blank around 60 times, and lynched.

At the time of the incident, law enforcement went on record as saying that out of the mob of 20, 15 had been identified. Still, no one was ever charged, and with grand jury transcripts firmly sealed, those people have never been publicly identified — in spite of repeated attempts to get court orders to open the files.

In 2013, Wayne Watson stepped forward with claims that his uncle, Charlie Peppers, had often talked about being one of the KKK members who had taken part in the slaughter. Peppers denies the charges — and that he was ever a member of the KKK — saying, "The Blacks are blaming people that didn't even know what happened back then."