The Evolution Of Fingerprint Technology Through The Years

If fingerprints were not unknown even in ancient times, the rise of anonymity in the 19th century inspired many to explore the possibilities of fingerprint identification for legal, forensic, and other needs. What started as a simple print on paper cards developed into intricate technologies capable of taking and storing fingerprints, as well as systems to search through growing databases.

Throughout the years, it became clear fingerprints are not the only part of bodies that can be measured. DNA fingerprinting opened the door to complex biological tracing useful for solving crimes, but also for determining characteristics of a person, such as their lifestyle habits and preferences. Biometic technologies have evolved even further, with iris scanners and facial recognition cameras coming into popular use in the 21st century.

With emerging and evolving technology comes controversy, including inconsistencies in data storage, data sharing, and even bias stemming from contextual information, as per Forensic Science International. Some even argue that such technology furthers a system of oppression, as per Al Jazeera, allowing governmental control with surveillance.

Whether good or bad, helpful or hurtful, these advancements are only getting more sophisticated. Here is the evolution of fingerprint technology through the years.

Fingerprints as identification existed in ancient times

Leaving a trace with hands and fingerprints is as old as humanity -– the oldest discovered fingerprints belonged to Neanderthals, notes Atlas Obscura. But there are many examples of ancient people utilizing their prints as a form of identification.

According to David R. Ashbaugh in "Quantitative-Qualitative Friction Ridge Analysis," some of the earliest examples of fingerprinting include a petraglyph tracing of a hand found in Kejimkujik Lake in Nova Scotia and Neolithic carvings from I'ille de Gavrinis Stone in France imitating friction ridge patterns, or the patterns of the skin along the fingers and palm. However the real intention of these artists is hard to confirm.

Fingerprints left as forms of identification have been seen in many pieces of ancient pottery, especially through the Middle East, where they were used as the potter's trademark. In addition, in ancient times, people used their fingerprints as a signature. Babylonians employed fingerprinting as a means to sign contracts, pressing their fingers into clay tablets. In China, ruler Ts-In-She (246-210 B.C) and other officials in the country used fingerprinting on clay seals when signing documents.

Today fingerprinting is most often associated with identifying criminals. That practice can be traced as far back as to Hammurabi (1792-1750 B.C.), where state officials fingerprinted those they arrested. When silk and paper printing was discovered, hand printing became a valid method of credibility. But apparently, they were also used as evidence in criminal cases, as they were found in a trial document dating back to 300 B.C.

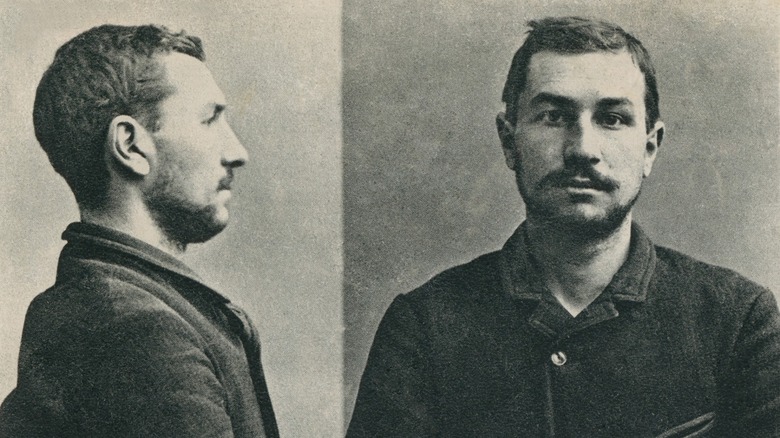

The Bertillon system

While the Bertillon system didn't use fingerprints, its contribution was immense, as it set the future of identity classification systems often still in use today. As per the National Library of Medicine, French criminologist Alphonse Bertillon came up with his system in 1879, combining the growing usage of photography with detailed body measurements and feature classification, all documented on cards that could be searched.

Measured were head length and breadth, along with eye color, length of middle and little finger, left foot, and cubit (the distance between the elbow and the end of the middle finger). These became very specific markers that could help law enforcement identify suspects and repeat offenders.

While the system was widely used at the end of the 19th century, it soon went out of fashion, as its flaws became more apparent. According to the New York State Division of Criminal Justice Services, at the beginning of the 20th century, fingerprinting took over the Bertillon system, as it was more straightforward.

Nevertheless, Bertillon's contribution to modern forensic methods can still be found in crime scene photography, as he was the first person to come up with the idea that crime scenes needed to be photographed top-down for later examination. Mug shots were his invention as well (via National Library of Medicine).

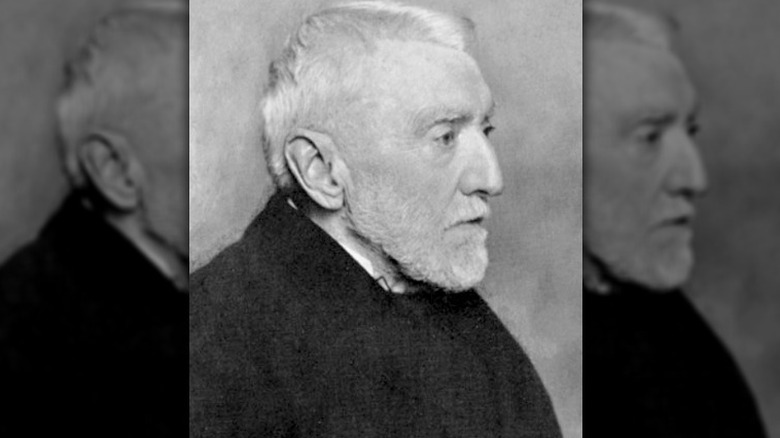

Henry Faulds scraped his fingerprints off

With the industrialisation of the 19th century, city populations were booming, notes Brewminate, and urban anonymity was born. Police needed a way to identify people, and the Bertillon method was becoming more challenging. While fingerprints were nothing new, the idea that fingerprinting could help identify strangers was novel, and several people in different places started to further explore it.

One of them was Henry Faulds, a doctor from Scotland, who worked as a clergyman in Japan in the 1870s. Discovery of old fingerprints on ancient Japanese pottery led him to experiment with fingerprinting on his hospital colleagues. By dipping their fingers in ink and pressing them to paper, he realized none were the same. He even wrote a letter to Charles Darwin, reports the BBC, but Darwin wasn't interested and sent the letter on to Francis Galton, who published a book on fingerprinting several years later, largely appropriating Fauld's ideas, writes Colin Beavan in his book, "Fingerprints."

According to Brewminate, Faulds conducted several trials to test his theory about the possible usage of fingerprinting in criminal matters. In one case, he managed to solve a small crime, when he caught a hospital employee stealing alcohol by comparing the fingerprints left on the glass to one he'd taken from a coworker. In another exercise, he and some of his students scraped their fingerprints off to see if they would grow back — which they did. In 1880 Faulds published a research paper in Nature, explaining his discoveries and their value for criminal identification.

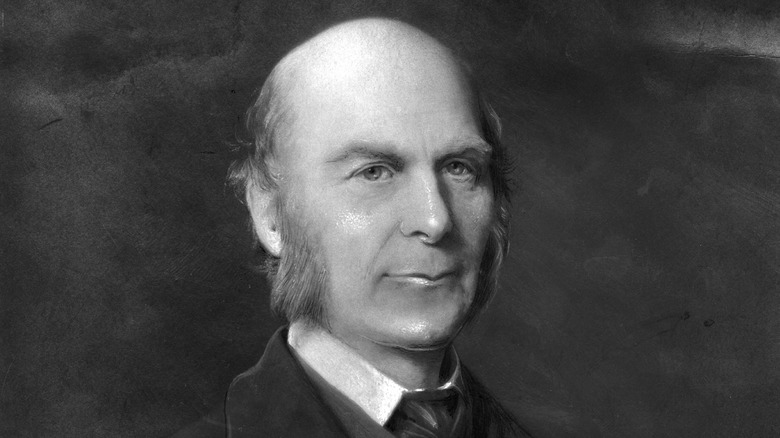

Francis Galton's book and methods of fingerprinting

If Francis Galton wasn't interested in fingerprinting when he got the letter from Henry Faulds, this changed in 1888, when the Royal Institute invited him to give a lecture on personal idenification (via the New York State Division of Criminal Justice Services). According to Colin Beavan in his book, "Fingerprints," Galton was over-privileged and over-indulged, and his belief in genetic superiority led him to his work on heredity and anthropometry, or the study of the physical measurements of an individual.

As Beavan writes, Galton actually looked to Faulds' work to further his study but largely left him out of the conversation and credit when it was time to give the lecture and otherwise set himself up as an expert. Regardless of his shady behavior, Galton's work did contribute to the science. His research showed that finger ridge details — essentially the patterns of lines in a fingerprint — should be used when comparing prints for identification.

In 1892, he published the first book of his collected research, titled "Finger Prints." Along with describing its history and the science around fingerprints, he carefully explained different techniques to collect fingerprints, including using ink or water colors to impress the fingertip ridges to paper. Other methods devised included smoke printing, where fingerprints are pressed into a smoked glass and then pressed into paper,

While Faulds had initially suggested the use of fingerprinting for forensic identification to an unconvinced Scotland Yard in 1886, writes Beavan, it was Galton who convinced them to start incorporating fingerprinting as a method of identification, in combination with the Bertillon system, eight years later, as per the NY Division of Criminal Justice Services.

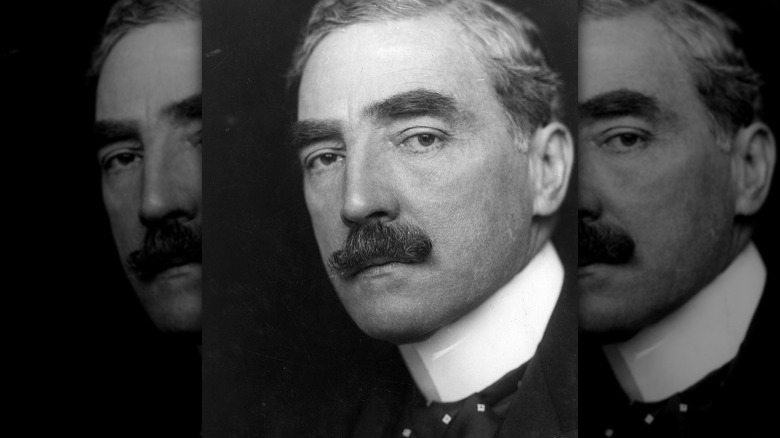

The Henry Classification System

Colin Beavan writes in his book, "Fingerprints, that Francis Galton's research got the attention of Sir Edward Henry, chief of police in the Bengal District of India. At the time, Henry was dealing with the criminal elements of the local indigenous population and how to identify and keep track of them. Initially he adopted the Bertillion system with both success and frustration. Thanks to a suggestion from a colleague, Henry was introduced to some of Galton's work and began incorporating fingerprints into the staff protocol. In fact the two even struck up a friendship and agreed to share information to advance the science and system, notes Beavan.

While Henry was a proponent of the fingerprinting method, he was also aware of the challenges. As the New York State Division of Criminal Justice Services notes, the method of organizing fingerprint records was cumbersome, as there lacked primary groupings that would simplify the search process and essentially be easier for those using the system.

According to Henry the solution came to him on a train ride in 1896, although many suspect his assistant, mathematician Khan Bahadur Azizul Haque, solved the problem. Regardless, the Henry Classification System was created, based on assigning numerical values to 10 fingers and only adding the numbers where a whorl pattern appeared. This system created 1,024 primary groups to search from.

India adopted the system in 1897, with Scotland Yard following in 1900. A year later, Henry moved back to the United Kingdom to help establish Scotland Yard's Central Fingerprint Bureau.

Fingerprinting and the Argentine Plan for Universal Identification

Sir Edward Henry wasn't the only police official inspired by Francis Galton's research. As Colin Beavan writes in "Fingerprints," Juan Vucetich, an official in the La Plata Police Office of Identification and Statistics in Argentina, had come across some of Galton's research in 1891 and started to experiment with fingerprinting on his own. He collected fingerprints of criminals, developing a system for classification, which he named dactyloscopy, according to National Library of Medicine. In fact, it was through his efforts that fingerprint evidence was used for the first time to solve a murder in 1892.

As Beavan details, by 1894 Vucetich refined his system — while he utilized the patterns, like whorls, that Galton had identified, he pioneered the use of all 10 fingers for printing and identification, giving him over a million primary classifications. He also eschewed the Bertillon system, arguing the fingerprints should be enough.

His system predated Henry's (and included similarities like processing all 10 fingers), so technically Vucetich developed the first system, as the National Library of Medicine notes. Sadly, he wouldn't truly get the credit, with Europe largely adopting and acknowleding Henry's work. Argentina did adopt Vucetich's fingerprint method for their citizen identification system, resembling modern passports, in 1900. Vucetich also published his findings in 1904 under the title "Dactiloscopía Comparada."

At the beginning of 20th century, researchers in different countries developed their own system on the basis of either Henry's or Vucetich's discoveries. Some combined both, designing upgrades that would allow processing of larger populations, explains Laura A. Hutchins in "The Fingerprint Sourcebook."

Automated Fingerprint Identification Systems

As Colin Beavan writes in "Fingerprints," New York's Bureau of Prisons became the first in the United States to adopt fingerprinting for identification purposes. By 1906, law enforcement all across the U.S. began to use the Henry Classification System, as per NY's Division of Criminal Justice Services.

The FBI established the Identification Division department in 1924, with the sole purpose of serving as the central database of criminal identification records, explains criminal defense specialist Kenneth R. Moses in "The Fingerprint Sourcebook." The system of collecting and storing fingerprints was already in place, but with a growing number of fingerprint records, the need for easier classification grew as well. The slow process of manually searching through databases was stalling legal action, and the idea of automated classification was born.

In 1934, the FBI tested a method that incorporated punch cards and sorting machines but abandoned it soon after, according to Laura A. Hutchins in "The Fingerprint Sourcebook." It wasn't until the 1967, after computers entered the workforce, that the first national digital criminal database, the National Crime Information Center (NCIC), was created in the U.S. NCIC classification creates alpha-numerica codes for the specific patterns of each finger, without the need for combining fingers like the Henry system. While it did accelerate the search process to some extent, it still wasn't able to specifically identify one fingerprint out of many, or collect one digitally.

In 1972, the first automatic fingerprint reader was set up in Washington, and the modern Automated Identification System was born. First, AIS tried to follow the Henry method, which was still time consuming, so the system transitioned to the classification codes from the NCIC. In the 1980's, AIS became AFIS (Automated Fingerprint Identification System) — a fully digital system that didn't compare actual fingerprints anymore but rather mathematical maps of the small features and patterns of the print.

The discovery of DNA fingerprinting

If fingerprinting was the forensic method of the 20th century, the new century offers expansion in the fields of DNA profiling, as per the journal Investigative Genetics.

In the 1980's, U.K. scientist Alec Jeffrey revealed that each individual carries his own genetic DNA heap, which can help identify the person after traces of DNA are left behind. He called this method DNA fingerprinting or forensic genetic fingerprinting, and its practicality was soon picked up by law enforcement and agencies around the world. The method is not only applicable to criminal and forensic cases but has a great potential in biological disciplines, such is animal conservation.

DNA profiling really took off in the 1990's, advancing Jeffrey's original method by transitioning to more simplified, straightforward, and exact processes as technology for DNA testing improved, along with new discoveries in genetic sciences. Even if there is no DNA match, which could reveal the offender immediately, DNA analysis can display family ties, biogeographic origin, and other clues that help to find the owner of the DNA traces.

Today, DNA databases exist all over the world, and they are getting bigger and bigger. Many question the ethics, including the inventor Alec Jeffreys, who challenged the U.K. police and their habit of collecting DNA samples from people who were never charged or convicted.

Automatic fingerprint scanners in personal and public use

Fingerprint technology has evolved from its application in criminal identification to a technology for personal use, largely thanks to the advances in cell phones in the 2000s.

Automatic fingerprint readers became more precise with smartphones, employing different technologies. Today, there are three main types of scanner fingerprint technology: optical, capacitive, and ultrasonic, reports Make Use Of. The optical scanner utilizes the light falling on a three-sided prism inside the scanner, functioning similar to the digital camera. Capacitive fingerprint scanners work without the light, more like a touch screen, catching the difference in the electrical charge of the fingerprint ridges, matching them with the stored fingerprint. Ultrasonic fingerprint scanners employ sound, bouncing between the fingerprint scanner and the sensor in it.

With the rise of mobile phones in the 2000s, followed by the smartphone craze in the 2010s, fingerprinting went mainstream. Today, it is not unusual to unlock your mobile with a touch of a finger. The very first fingerprint scanner built into a phone, Panatech Gi100, was released in 2004. It took another 10 years for the feature to occupy the flagship phones of Samsung and Apple, evolving from a backside scanner to newer, digital touch screen versions.

But automatic fingerprint readers haven't been for cell phones only — they are becoming more common in public and private institutions. An Australian high school built in the readers into school toilets in 2022 to prevent vandalism and monitor pupils during lectures, as per The Guardian. Some think this is an invasion of privacy, while The Guardian also noted that parents were notified and consulted.

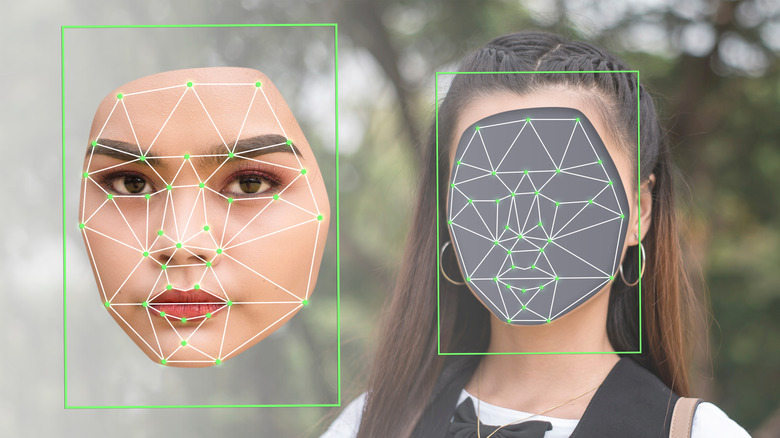

The rise of biometrics

New methods for identification are developed every day, like face recognition cameras, iris scanners, and voice fingerprints. Where simply the ridges and patterns of a finger sufficed to identify and document individuals, now law enforcement and government agencies can utilize several methods, along with practical applicaations for personal use.

According to Wired, initial research in computer facial recognition dates back to the 1960s, when mathematician Woody Bledsoe and his colleagues at Panoramic worked on the goal to teach computers how to recognize 10 faces. Their research was secretly supported by the CIA but, facial recognition technology didn't really take off until the 2010's –- when computers were more advanced and the arrival of social media enabled an eternal supply of digital imagery.

Essentially the technology captures a photo of a face or scans, measures, and maps a person's features to compare to images in a database. If a match is found, the system verifies or identifies the person (via Avast).

The future of total control

The use of Iris scans, fingerprinting, and facial recognition is spreading fast all across the world. Many question the need for this constant surveillance, as privacy is becoming scarce.

According to The Guardian, biometric technology like facial recognition has been used as a form of payment transaction, to determine COVID vaccine status, and even to scan for potential shoplifters. But as the outlet argues, this only normalizes the use of one's body as a transaction, which is, in a profit-oriented society, very ambiguous.

One of the biggest threats is the secretive nature of the technology's use, with facial recognition systems becoming a part of many public and private spaces, without people's consent. Algorithms are known to be extremely biased, further perpetuating racial, gender, and other stereotypes (via The Guardian). And several scandals broke out after it turned out that the delicate personal data was exploited by corporations, such as Google.

Fingerprints, as well as DNA fingerprinting, can reveal much more about the individual than just their identity, which begs the question of how invasive these systems really need to be. Scientists can detect whether a person is a smoker or a heavy drug user, and they can even detect how much caffeine a person drinks just from their fingerprints, as per New Scientist. Companies employ "emotional analysis" face recognition techniques to select employees for example, reports The Guardian, but its practical application is dubious at best, illegal at worst.