The Terrifying Story Of Albert's Swarm

In 1875, physician and amateur meteorologist Dr. Albert Child of the U.S. Signal Corps recorded a wonder of nature. But not all wonders are good, and what Child recorded was certain of the bad type. A locust swarm of stupefying proportions was winging over him in Nebraska. Possibly taking shape just south of Colorado, trillions of locusts swept from the Rockies into the Great Plains in a swath covering not only Colorado and Nebraska, but also Iowa, Missouri, and Minnesota.

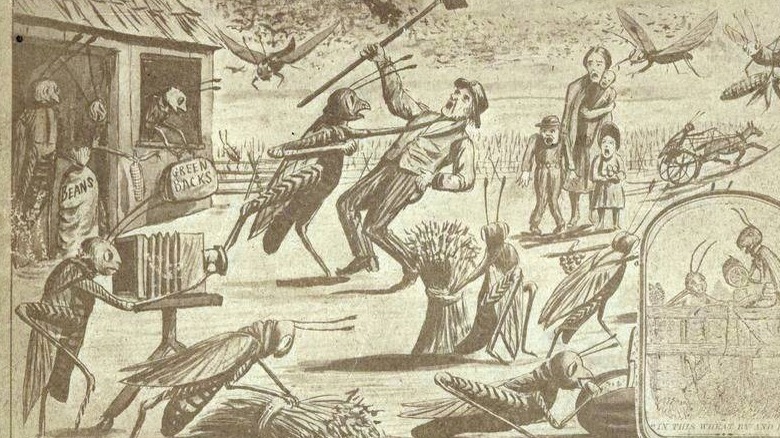

Although Albert's Swarm, as it came to be known, is one of the greatest natural disasters to ever befall the United States, time has reduced it to barely a footnote in American history. Yet eyewitness accounts tell a freakish scene, of locusts filling the air for miles and being two to three inches deep on the ground. Such was their number, the sound of their eating was actually audible. And then, mysteriously, the entire species died out by the early 1900s. Locust swarms hit a nightmare nerve — just read the story about the Biblical plague of locusts. Read on to discover one of the worst invasive species disasters in history, one every American farmer hopes never to deal with again.

The culprit: Menalopus spretus

The locust responsible for Albert's Swarm was just one species of locust, the Rocky Mountain locust, otherwise known as Menalopus spretus. As described by the University of Michigan Museum of Zoology, the insect measured an average length of under four centimeters and under normal conditions inhabited the high, dry valleys of the east-facing slope of the Rocky Mountains. The insect was generally brownish-yellow to gray, with contrasting black markings on the head and lateral lobes of parts of the thorax. The hind tibia was blue or dark red.

Entomological records for the American frontier in the late 1800s are spotty, but Bug Guide estimates the range of Menalopus stretched from British Columbia through Montana, Wyoming, Idaho, and the western Dakotas. Evidence suggests a sub-permanent region extended from this home range into the western half of Nebraska and the northeast part of Colorado. Egg clutches, buried just underground, could number as high as 100. Due to a lack of records, there is nothing to suggest Menalopus was anything else other than just one more Midwestern grasshopper until something caused it to swarm in the 1870s.

Once it did, however, public infamy was swift to follow. Just look at the name: Bug Guide records that alternate monikers for the Rocky Mountain locust were "hateful migratory locust" and "hateful grasshopper." Indeed, the species name of spretus is Latin for "despised."

A bit of swarm science

According to WorldAtlas, the difference between a grasshopper and a locust is that a grasshopper remains solitary for life, whereas a locust is a grasshopper species that has the potential to swarm provided the right conditions. Proximity seems to be the key. Set off by sudden rainfall (per LiveScience) or drought (per History.com), grasshoppers begin to congregate. This closeness to one another ignites a serotonin storm in the brains of certain species of grasshoppers, shifting them into what etymologists call a "gregarious phase" that is herd-like. They grow larger and change color. A locust is born.

Once rewired into a gregarious form, a small group of locusts can attract and absorb other individuals and even other groups, reprogramming them to create a swarm. Scientists call this mass a "superorganism," of individuals that act as a single creature. Always on the hunt for food, locusts then do en masse what grasshoppers do alone: eat. But with each locust eating its weight in a day, imagine how much grub a swarm of billions could take down.

A locust swarm eats any plant in sight, crossing vast amounts of territory to do so. Swarms can even self-sustain to a degree. Because locusts birth more locusts, not grasshoppers. And a swarm can place so many locusts in one place at one time, breeding occurs on a massive scale that leads to "repeat swarms" that can persist for years.

The scene: the Midwest in 1875

By the time of Albert's Swarm, the region of North America now known as the American Midwest was going through unprecedented change. With the Union victory in 1865, the American Civil War had been over by a decade, and the Reconstruction Era was well underway. Freed from wartime responsibilities, settlers from both the North and South began moving into the Midwest, and by 1875, the central region of the modern United States was already carved into recognizable sections. Kansas became a state in 1861, with Nebraska following in 1867. Colorado, the Dakotas, Montana, and Minnesota were all declared territories.

What had been the territory of Native American tribes, whose population for everything north of the Rio Grande could have been as low as 900,000 before colonization (per Britannica), was experiencing a population boom never seen before. Going by the 1870 census, Iowa alone had more than 1 million people, while Kansas counted 364,399. According to the Kansas Historical Society, "several thousand" Russo-Germans settled in the state in 1874 with the intention of setting up farms after migration. Little did they know, they would soon be unwitting targets for the coming swarm.

Albert's Swarm's massive size

It is hard to fathom just how big Albert's Swarm was. Namesake Albert Child, working in modern-day Nebraska, estimated that the swarm was 110 miles wide and ¼ to ½-miles thick. He measured these dimensions using the local telegraph network, sending messages up and down the lines to see which communities were impacted and which were spared, and then adding his own observations from a telescope.

The swarm began in August 1875, starting in Colorado and moving east towards Minnesota and the Great Lakes (via the Star Tribune). Child recorded that it took five days for the locust horde, moving at about 15 miles per hour, to cross over him in Nebraska. Exactly how many locusts comprised the swarm will never be known, but it could have been anywhere between 3.5 to 12.5 trillion — equating to somewhere around 27.5 million tons of biomass.

LiveScience reports Albert's Swarm as the largest number of animals in a group ever recorded by a human, equaling, per The New York Times, "the combined area of Connecticut, Delaware, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, and Vermont."

A famous author bore witness to Albert's Storm

According to The New York Times, Albert's Swarm looked like a "glittering cloud," from a distance, which was likely the result of sunlight reflecting off countless locust wings. Albert Child himself wrote (via the United States Entomological Commission), "It seemed like piercing the milky-way of the heavens; my glass found no limits to them. They might have been a mile or more in depth."

But perhaps the most famous eyewitness to Albert's Swarm was a little girl in Minnesota named Laura Ingalls Wilder, who wrote "Little House on the Prairie." In "On the Banks of Plum Creek," (via Lapham's Quarterly) she noted that, "a cloud was over the sun. It was not like any cloud they had ever seen before. It was a cloud of something like snowflakes but they were larger than snowflakes and thin and glittering. Light shone through each flickering particle."

Albert's Swarm was one of many swarms

Albert's Swarm was not a fluke for North America; missionaries in modern-day California had recorded locust infestations as early as 1722, according to History Net. Indeed, what happened in 1875 seems to have been the peak of a cycle that began in 1873, during which a locust plague swept into Minnesota and devastated 500,000 acres of cropland before a harsh winter in 1877 killed the locust eggs lurking in the soil (via Star Tribune).

Kansas fared no better. In 1874, a swarm of 120 billion individual insects forced westward-heading settlers to either turnaround and flee back east or give up on the Great Plains entirely and pushed on to California. Altogether, the Kansas swarm dealt a staggering $200 million economic blow to local farmers, eating a 100-mile-wide path of destruction all the way to Texas. Some families starved to death.

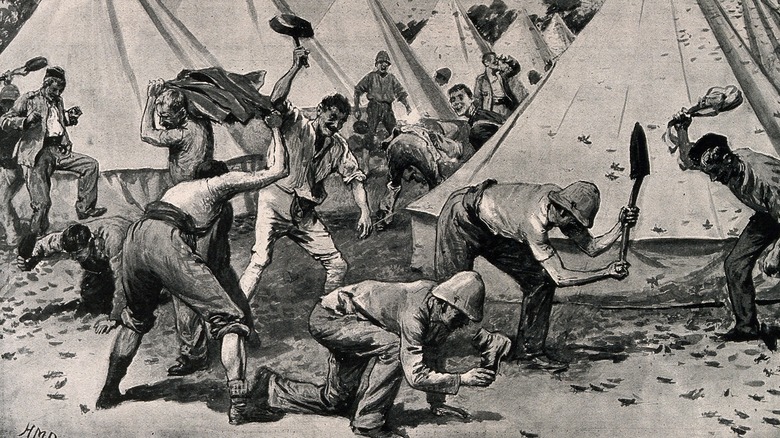

Even after the locust years of the 1870s, the phenomenon persisted. Another swarm hit Iowa, Nebraska, and South Dakota in 1931. As History notes, the region was already reeling from a drought, and the plague made a bad situation worse. What crops survived the drought were eaten down to the soil. Locusts returned in 1937, per the U.S. National Guard. This time, people fought back with flamethrowers and explosives. But the locusts still won.

Albert's Swarm cost farmers ... a lot

Locust superorganisms the size of Albert's Swarm reportedly cost somewhere in the ballpark of $200 million in damages, which in modern times would equate to a price tag more than doubled. According to "An Excerpt of Locust," a "typical" swarm can devour 50 tons of vegetation a day, and overwhelmed farmers tried everything from poison to dynamite to ward off the locusts.

According to The New York Times, some farmers threw blankets over their vegetable gardens, but the locusts only went on to eat the blankets (and then the vegetables they covered). Apple trees were chewed to stumps, as were wild trees like spruce. "An Excerpt of Locust," describes one farmer who found the locusts trying to eat his horse. Trains had to halt on their tracks because the crushed bodies of locusts made the rails too slippery to continue traveling. The devastation was so thorough, says the Denver Post, that Albert's Swarm was the first time the federal government stepped in to lend a hand in the aftermath of a natural disaster, with the Army providing food to stricken communities.

What caused Albert's Swarm?

History Net notes that the winters of 1873 and 1874 were unusually hard and caused drought. But it wasn't just any drought. According to the Royal Meteorological Society, 1873 was an El Niño year, which caused variouchs weather patterns to form not only all over the ocean but also in the continents surrounding it. According to NOAA, a typical El Niño current pushes the Pacific jet stream, usually over the U.S.-Mexico border, even further south. This, in turn, pulls warm, dry air into the Rocky Mountains and Great Plains, setting off the drought conditions that can trigger a locust swarm.

According to AgriLife Today, grasshoppers and locusts thrive in such weather, as do their eggs. Plus, fungi are the greatest threat to grasshopper eggs and act as a natural break against the insect's numbers, but hot, dry conditions stifle fungi growth — allowing more locusts to hatch.

Locust swarms can cross oceans

Locusts continue to be a problem in various parts of the world. In this year alone, locust swarms hit South Africa and Sardinia. According to OCHA, one swarm originating in the Horn of Africa impacted more than a dozen countries. History is positively spangled with locust swarms, from the Levant to India to China. (In 2000, China considered enlisting 100,000 ducks in its war on locusts.) But science found a much older, and far more worrying, locust swarm migration that spanned the entire Atlantic Ocean. A 2005 study in Proceedings of the Royal Society of London revealed that locusts originally found in Africa managed to cross the Atlantic three to five million years ago.

As unlikely as this sounds, evidence points to this actually happening. Back in 1988, UPI reported that "unprecedented swarms" of African locusts rode Atlantic winds to touch down in the Caribbean, threatening local sugarcane and corn crops. The 2005 study adds that the same thing happened again in 1998. Luckily, the moist, humid Caribbean is hostile to desert locusts. Nevertheless, it suggests that African locusts could establish themselves permanently in the Americas again given the right conditions and landing point, bringing destruction along the way.

How the locusts disappeared

It seems impossible that a species numbering in the trillions could disappear entirely just 20 years later, but that seems to have happened with Menalopus spretus. In a classic case of ecological boom-and-bust, Albert's Swarm seems to have been the last hurrah for the species. According to SciShow, a temporary crash in a locust population after a swarm is not by itself unusual, but for this species, the crash was permanent. What happened?

The University of Michigan Museum of Zoology posits that the people this insect plagued in 1875 were the same ones that obliterated the Rocky Mountain locust: farmers. The locust's native breeding habitat was high, east-facing drylands on the Rocky Mountains along sandy riverbeds. This turned out to be a critical weak point in the Menalopus life cycle, as it was the same landform that incoming farmers tilled for crops. While the locusts could breed outside these environments, it resulted in a single generation at most, and the species needed its original range to survive long-term.

Although the extinction is one scientists still can't explain fully, SciShow highlights a theory proposed in 1990 suggesting that by pure accident, thousands of the locusts' eggs were killed by simple plowing. It is not to say this alone annihilated every last Menalopus, but the tilling of the soil took out such a huge portion of the population that there weren't enough survivors to keep the species going. The last live specimen of Menalopus was collected in 1902.

The possibility of resurgence

A 2003 article in Discover Magazine points out that when the Rocky Mountain locust vanished, it left a vacancy in the ecosystem another species could evolve to fill. As SciShow points out, with the extinction of Menalopus spretus, North America became the only continent besides ice-cold Antarctica without a swarming locust. It is a waiting niche.

Another species of grasshopper, the Melanoplus sanguinipes, already exhibits migratory behavior (as individuals) similar to that of its cousin, Menalopus spretus. Another member of the genus, Melanoplus femurrubrum, caused a major outbreak in Idaho in 2001. A completely different species, Camnulla pellucida, was behind a Colorado infestation in 2002. These events did not result in a "swarm" per se, but scientists worry about the potential for one.

Discover Magazine also raises the possibility that Menalopus spretus is not extinct at all, but rather, simply has not recently swarmed in its infamous and recognizable locust form. It's possible the Menalopus spretus may very well be hiding out in isolated valleys amid the Rockies, biding time until the next environmental trigger.