The Messed Up Truth About The Reconstruction Era

The Civil War irrevocably changed this country. Some of those changes were for the good, of course—slavery was abolished, and long-simmering conflicts between the states and the federal government were finally settled, resulting in more coherent and effective leadership.

But some of those changes weren't so great. The negative outcomes of the Civil War range from racism's reinvention as the sneaky, quasi-legal Jim Crow laws and segregationist "separate but equal" policies, to the aggressive and racially biased policing that defines American law enforcement today. But it wasn't supposed to be this way. After the Civil War, the former Confederate states were plunged into a period of military occupation and reorganization commonly referred to as Reconstruction. Contrary to popular belief, this had very little to do with literally rebuilding the ruined cities and decimated farms of the South and more to do with an attempt to reconstruct everything about Southern life and politics.

But after an auspicious start, Reconstruction slowly collapsed under the weight of political reality and short-sighted decisions. Here's the messed-up truth about the Reconstruction era.

Reconstruction ended because it was working

Starting in the 20th Century, Southerners began a campaign to rebrand everything about the Civil War, casting the Antebellum South as a genteel and civilized culture and the Civil War as a fight over State's Rights, not slavery. Part of this "Lost Cause" mythology was to argue that Reconstruction was a disorganized disaster that ended before its work was done because it was failing, and failing badly.

But this isn't true. As The Washington Post writes, Reconstruction was working very well, at least at first. In fact, the reason the Southern power brokers began to work so hard to undermine it was precisely because the Republican governments elected immediately after the war ended moved quickly to pass popular laws. Republicans got as much as 40 percent of the white vote, and nearly 100 percent of the Black vote—making the old guard extremely nervous.

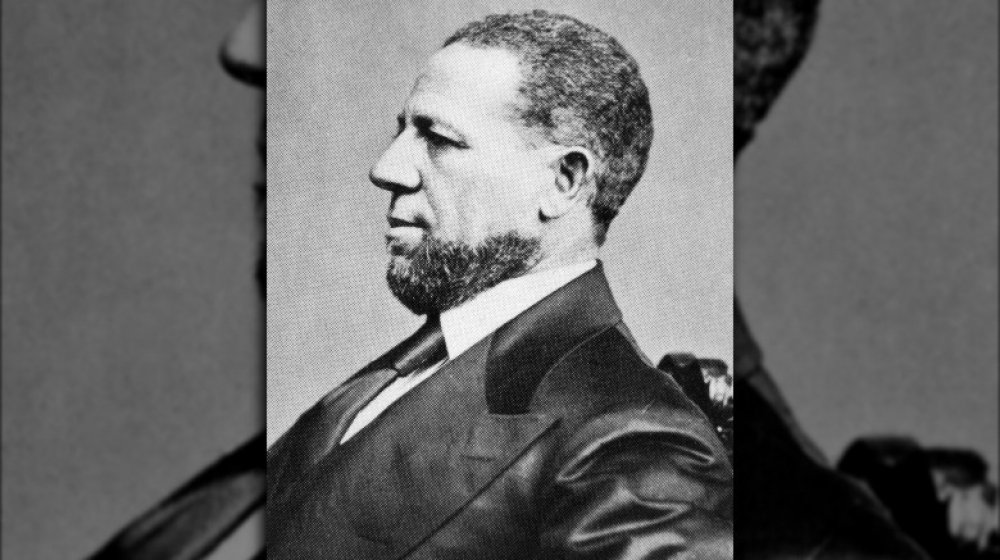

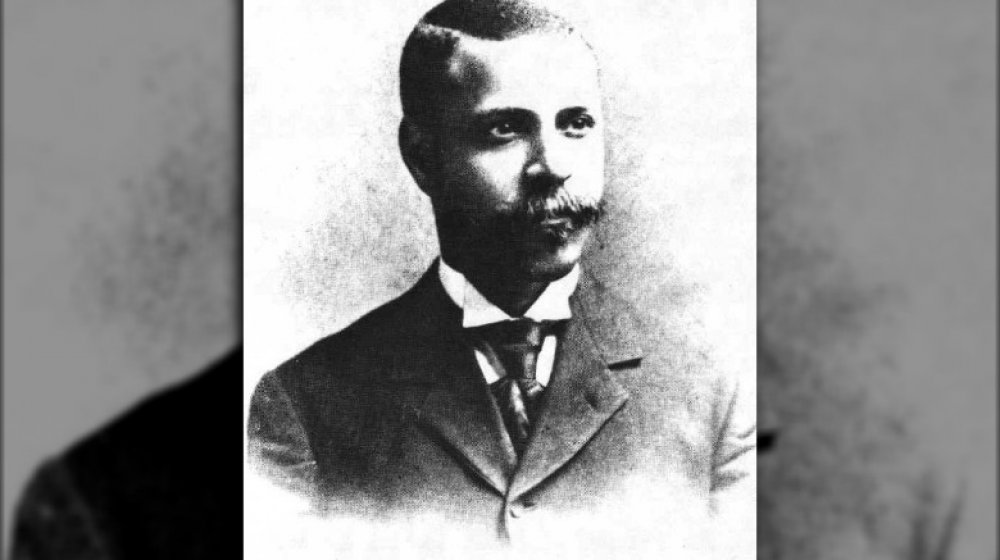

The Black community in the South was thriving as well. As History notes, Blacks moved quickly to get organized, holding meetings, staging parades, and creating Equal Rights Leagues to push for legal rights and the vote. Within a few years more than 600 Black Americans were elected to state legislatures, 16 were elected to Congress, hundreds held local offices, and in 1870 Hiram Revels became the first Black Senator in U.S. history. The reason Reconstruction was undermined and resisted at every turn by a desperate group of racists was because it was working.

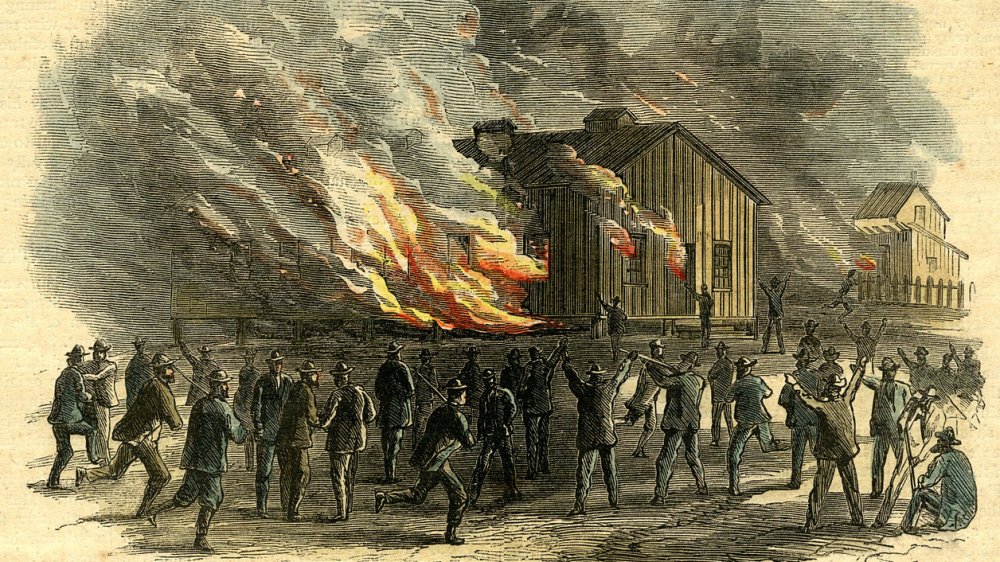

The violence was horrific

When white Southerners began to see that Reconstruction was actually working, empowering former slaves and forcing political reality onto the former Confederacy, their response was violent. Really violent. Since the old racist guard had been stripped of most of their political power, they had to resort to terrorism—and their targets were the newly-freed Blacks and the Republican politicians who were legislating in favor of their rights.

The violence was so terrible, in fact, Smithsonian Magazine reports that it's possible that as many as 53,000 Blacks were killed in the South between the end of the Civil War and the end of Reconstruction—which averages out to about five per day. And as PBS notes, there are startling individual statistics, like the fact that the Texas Freedmen's Bureau recorded over a thousand murders of Blacks between 1865 and 1866, with reasons like "Black man didn't tip his hat so I shot him" given on official reports.

The violence was systemic. Organizations like the Ku Klux Klan and the White League assassinated officials, tortured people, and burned houses—all in the name of restoring white supremacy, pushing Blacks back into an inferior position, and driving the Republican Party from the South. The truly messed-up thing about this is that it worked.

One vote could have changed everything

Reconstruction actually lasted a long time, and didn't just end on a dime. Many people date the end of Reconstruction to the Compromise of 1877, when the disputed Presidential election drove the Northern states to withdraw federal troops from the South and give the former Confederacy back most of its independence and power in order to secure the election of Rutherford B. Hayes.

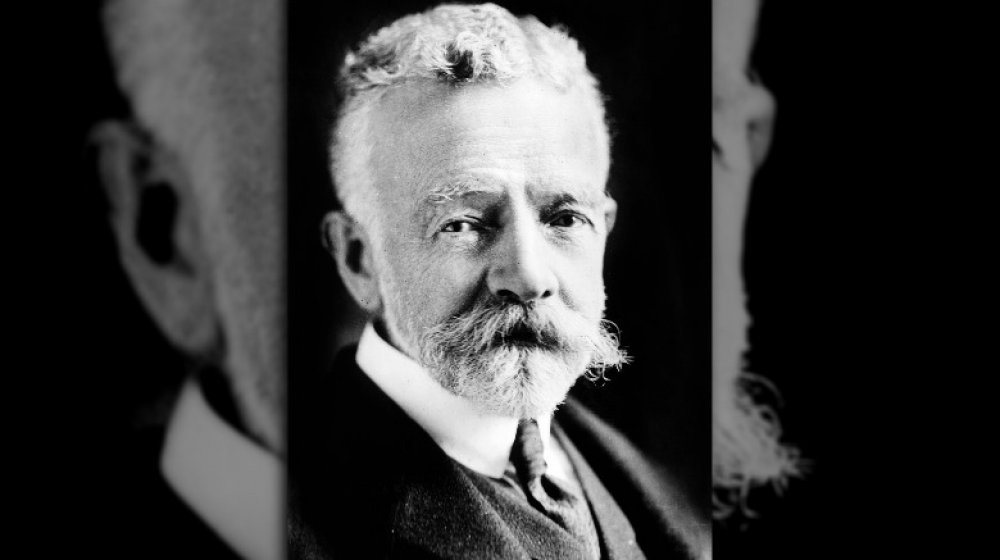

But as The Washington Post notes, it's not like Reconstruction ended immediately in 1877. For the next 13 years, Blacks voted in large numbers across the South and remained a potent political force. More importantly, the Republicans retained significant power even after losing control of the House of Representatives and the Senate. In fact, in 1890 there was one final chance to preserve at least some of the progress associated with Reconstruction in the form of the Federal Elections Act, often called the Lodge Bill after its author, Henry Cabot Lodge.

The Lodge Bill had a simple purpose: It authorized the federal government to ensure that all elections were fair, and would have empowered federal courts to appoint supervisors. Republicans managed to get the bill passed in the House by six votes, but it died in the Senate. Its defeat marked the last attempt by the Northern Republicans to fight for the voting rights of Blacks, and its failure all but ensured that Black political power would fade away, leading directly to the Jim Crow laws of the next century.

The KKK rose up during Reconstruction

The Confederacy's defeat in the Civil War was total. General Grant's belief in "total war" left the Southern economy and infrastructure a wreck, and the Southern United States was occupied by federal troops. In the immediate aftermath there was uncertainty on both sides as to the attitude that the North and the Republicans would have towards the defeated South.

As History notes, while General Robert E. Lee's surrender at Appomattox on April 9, 1865 is usually cited as the end of the Civil War, the fact is Lee only surrendered the Army of Northern Virginia. Several Confederate armies remained in the field and it was actually almost 16 months before the last of them officially surrendered. So it should be little surprise that a group of Confederate veterans founded the Ku Klux Klan in 1865.

History reports that the Klan grew quickly, and by 1870 had a chapter in every Southern State. What supercharged the KKK and encouraged them to become a violent terrorist group was Reconstruction. When it became clear that the North intended to force equal rights for Blacks and other changes onto Southern society, the KKK became one of the main tools of violence targeting Blacks and Republican politicians. As author Ron Chernow notes, they were such a threat that President Ulysses S. Grant launched a major—and almost successful—campaign to eradicate them. After Reconstruction ended, however, the KKK rose up again. By the 1920s, it sported about four million members.

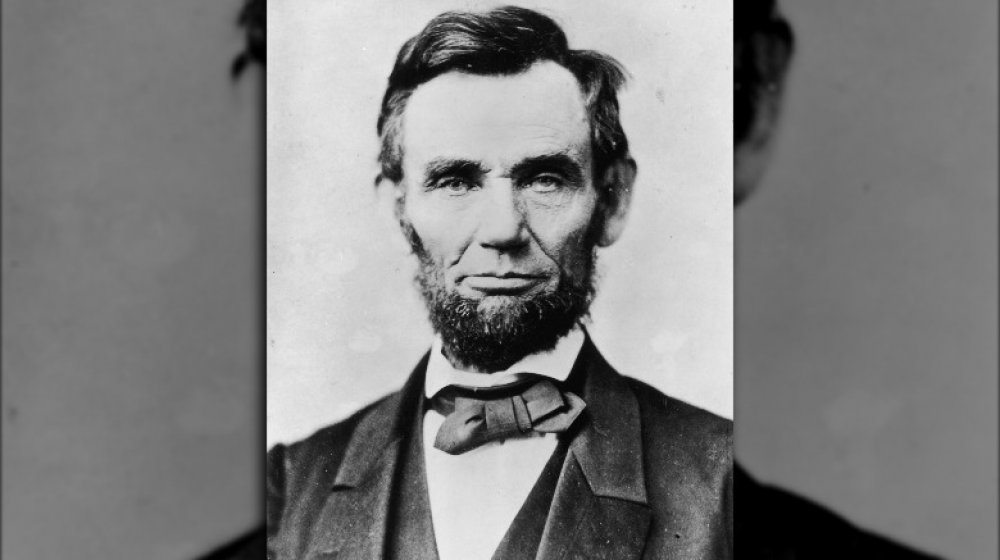

Reconstruction killed Lincoln

As the Civil War ended, the big question that loomed was how to deal with the defeated Confederacy. Although the South had been beaten, and was in economic shambles as a result of the war, there was disagreement on how to approach the rebels—and the millions of freed former slaves.

After a period of uncertainty wherein President Lincoln considered some alternatives (including the possibility of offering to "recolonize" the Black population), historian Jim Loewen notes that Lincoln settled on a firm policy of extending the full rights and privileges of citizenship to former slaves. Lincoln made this very clear towards the end of the war, and took initial steps to ensure these policies were carried out.

As The New Yorker notes, this likely sealed Lincoln's fate. While Lincoln was obviously unpopular among those sympathetic with the South and its cause, his future assassin hadn't yet made his decision. A speech Lincoln made in Washington D.C. expressing these sentiments caused John Wilkes Booth, in the audience, to realize he was talking about granting citizenship to Blacks. Enraged, Booth snarled to his companion, "Now, by God, I'll put him through. That is the last speech he will ever make." Shortly afterwards, Booth assassinated Lincoln at Ford's Theater.

Reconstruction was betrayed from within

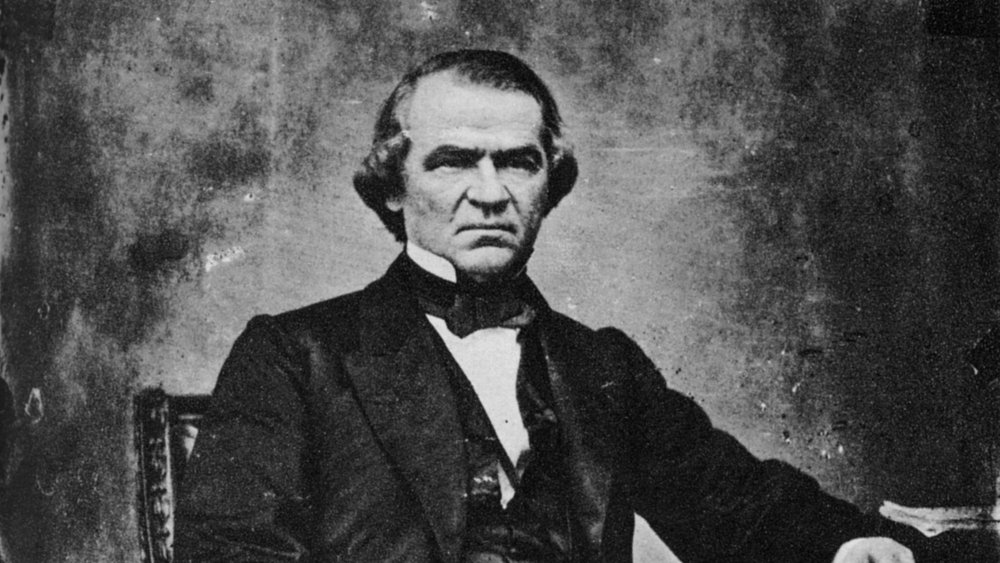

It's easy to imagine that if Abraham Lincoln had survived to lead the country through Reconstruction, things would have been much different. As it was, Lincoln was assassinated, and Reconstruction was doomed almost from the start, because Lincoln's Vice President, Andrew Johnson, became President.

As The New Yorker notes, Johnson was a racist with little education. His main attraction to Lincoln was that he was a Democrat from Tennessee who was also a fierce unionist, a Southerner who had remained loyal to the federal government. Lincoln was shoring up his support in the 1864 election, playing long-game chess—but it backfired spectacularly on everyone when he was killed and Johnson took charge.

As The Atlantic puts it, Johnson literally "did everything he could to sabotage efforts on behalf of the formerly enslaved." He openly and stubbornly opposed Reconstruction and efforts to punish the South or to protect the newly-won freedoms of Black Americans. He so enraged his own party that he was impeached—the first President to be tried in the Senate, where he escaped removal from office by a single vote. And then went right back to working against Reconstruction as hard as he could. By the time he left office in 1868, it was too late—the opportunity to effect real change in the South had passed.

The justification for the Civil War doomed Reconstruction

The Civil War was the culmination of decades of acrimonious disagreements and temporary compromises. When the Confederacy was declared in 1860, the United States had not even existed as a nation for Lincoln's famous "four score and seven years," so the question of whether the union was a voluntary agreement between sovereign states or something more centralized had never been settled. When war broke out, Lincoln needed a legal argument for the use of force—and a legal theory on how to treat the states that had rebelled.

As The New Yorker points out, what Lincoln settled on, broadly speaking, was that secession wasn't legal or allowable. As a result, the states had never actually seceded. In practical terms, what this meant was that the states that joined the Confederacy had never stopped being part of the United States, and as such were not foreign enemies. During the war this was a smart strategy, as it discouraged other countries from treating the Confederacy as a legitimate nation.

During Reconstruction, however, this strategy backfired. The South could argue that since the state governments had never actually left the Union, they should instantly reclaim all the rights and powers they'd had before the war. This idea made it very easy for the South to come back into the full flush of its political power—and to then use that power to inhibit and defeat efforts at Reconstruction.

The Supreme Court could have saved Reconstruction

Every citizen of the United States knows (or should know) the fundamentals of our government—that there are three co-equal branches. The legislature passes laws, the executive enforces those laws, and the judiciary interprets those laws. When there are questions about a law's validity or constitutional status, it usually ends up in front of the Supreme Court, which can make a final decision.

We're a nation of laws, so it's no surprise that Reconstruction took the form of a series of laws and constitutional amendments designed to reshape the power structures of the South and protect the rights and privileges of the newly-freed slaves. Or that many of those laws wound up being evaluated by the Supreme Court. And as NPR notes, the Supreme Court basically did its best to stop Reconstruction in its tracks. The Court found the Civil Rights Act of 1875 unconstitutional, ruled that Congress lacked authority to grant equal protections under the law to Blacks, and ruled that the Enforcement Act of 1871—intended to stop the KKK from organizing—was unconstitutional.

The Supreme Court, as The New Yorker writes, was ultimately responsible for not only the ruin of Reconstruction's efforts to level the playing field for Blacks in the South, but also for cementing in place the systemic racism of Jim Crow laws. This was accomplished in 1896 with the Court's ruling on Plessy v. Ferguson—the decision that gave us the pithy phrase "separate but equal" as it legitimized racial segregation.

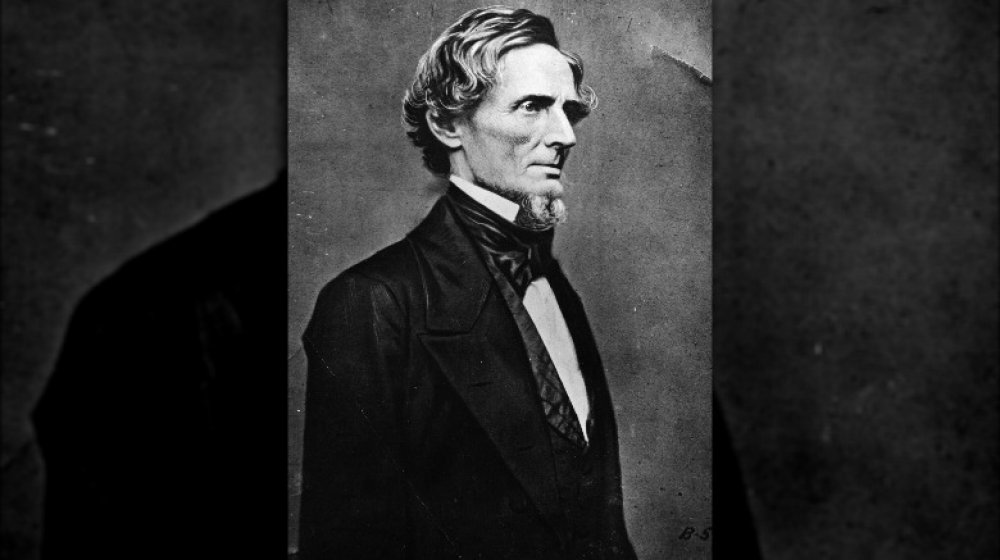

Traitors got away with it

Reconstruction—and our nation's history—might have been quite different if the men who led the Confederacy and caused one of the bloodiest wars of all time were punished in any way after the Civil War. As The Washington Post writes, for all of President Andrew Johnson's many, many flaws, he was an ardent Unionist. Johnson initially intended to zealously prosecute the leaders of the Confederacy.

But any attempt to punish the rebels ran up against several key obstacles. President Lincoln preferred to offer amnesty to most of the Confederates in the service of quickly healing the country. And when General Ulysses S. Grant accepted the surrender of Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia, he'd taken it upon himself to offer parole to all Confederate soldiers, establishing an officially lenient approach.

As Smithsonian Magazine notes, another reason no one was punished the rebellion had to do with a reluctance to test the legal questions. Confederate President Jefferson Davis was prepared to argue that he ceased to be a U.S. citizen when Mississippi left the union, and thus could not have committed treason. If he'd succeeded in court, it would have implied that secession was legal—and no one wanted that. Davis was released, and in 1868 President Johnson issued a blanket pardon to all former Confederates. The lack of punishment allowed the people who had caused the Civil War to simply return to their former roles of influence and power, completely undermining Reconstruction.

The US didn't have the resources to keep Reconstruction up

In the immediate aftermath of the Civil War the Union Army was an occupying force. With the Southern states in ruin, the army had to act as law enforcement, and while federal troops were around the newly-empowered Blacks had a chance at exercising their new rights and taking part in government. The presence of Federal troops made the former Confederates angry, but there was little they could do. For Reconstruction to have any real chance of working, those troops were a necessity.

Unfortunately, as Time explains, armies are expensive things. At the end of the Civil War the army was one million strong and completely dominated the decimated South. Just a year later, the army's numbers had shrunk to just 90,000. To put that in perspective, the former Confederacy was 750,000 square miles, and had a population of nine million. Policing an area of that size required more military muscle.

Instead of bulking up the army's presence in the South, however, the federal government reduced it. By 1871, there were just 4,300 troops left in the South. Unsurprisingly, terrorism and violence rose rapidly. Even though President Ulysses S. Grant made a valiant effort to destroy the Ku Klux Klan, the damage was done—as the same folks who'd fought a war to preserve slavery took back power, Blacks and Republicans were intimidated, murdered, and driven out of the South in part because they had no authority to appeal to.

The South rose again perfectly legally—by winning elections

After the Civil War, the victorious Republicans were divided on how to approach the South and Reconstruction. Some argued for harsh treatment—prosecution and full-on military occupation. Others, ultimately successful, argued that the best route was to reunite the country as quickly as possible. As a result, no real effort was made to punish the traitors who'd seceded from the Union, and despite legislation designed to codify voting and citizenship rights for Blacks in the South, the army was quickly removed from the South—and enforcement along with it.

As Time notes, this doomed Reconstruction to failure. Within a few years, the South had reclaimed its internal authority through the completely legal means of winning elections. Far from being destroyed by their defeat, the Democrats roared back to take over the House of Representatives in 1874, the Senate in 1878—and finally the Presidency in 1884.

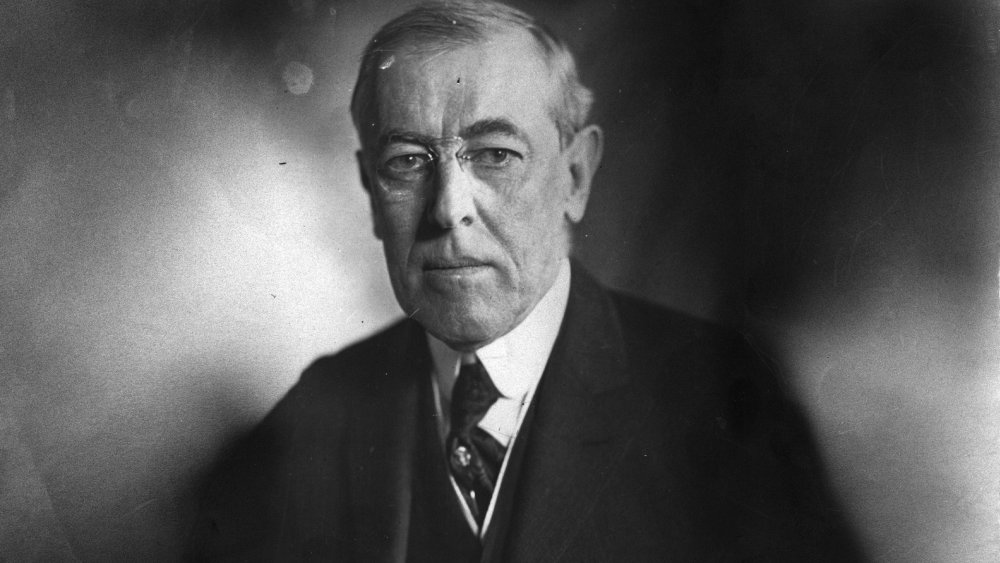

The final triumph of the South over Reconstruction came in 1920, when Woodrow Wilson became the first Southern-born President since the Civil War, throwing off the final traces of ignominy associated with the Confederacy. And as The Atlantic notes, Wilson brought with him precisely the racial attitudes you might expect, which is one reason why Princeton University removed his name from their public policy school and buildings.

Reconstruction destroyed the free 'Black Elite'

In discussions about the Civil War, slavery, and Reconstruction, it's often overlooked that there was a significant population of free Blacks in the United States at the time—and some possessed considerable wealth and social standing.

That's not to say that Blacks enjoyed anything close to equality in America at the time—in the South or the North. Most free Blacks were incredibly poor, and racism was prevalent everywhere, even in nominally "free" states without slavery. But as The Washington Post reports, there was a social strata of free Blacks who were relatively wealthy and even politically connected, even before the Civil War.

Reconstruction enhanced their position—at first. But the violent reaction that Reconstruction sparked in the South eventually destroyed the precarious position the "Black elite" had managed to maintain. Terrorist groups like the KKK and the White League waged an angry war of vengeance on Blacks and their white allies throughout the South, and made no distinction for wealth or social position. The erosion of political rights and the establishment of Jim Crow laws and legal "separate but equal" segregation diminished the wealth and influence of the old-guard free Black elite, nearly managing to erase them from history completely.