The Reason Cyprus Is Divided

For over 50 years, Cyprus has been divided, but the lines of its division were drawn much earlier. The buffer zone that runs through the island continues to be patrolled by UN peacekeeping soldiers, and for many, it's difficult to imagine any end in sight. Until border crossing points were put in place in 2003, Cypriots were unable to freely meet people from different parts of the country. And many who were displaced from their homes in both the northern and the southern areas of Cyprus have never been able to return.

While barriers like the Berlin Wall have fallen, the capital of Cyprus remains the last officially divided capital in the world, per The New York Times. And although deaths have dropped as the number of troops along the buffer zone have been decreased, The New York Times reports that "the buffer zone remains, no longer only a line on a map but a state of mind and way of life." But how was Cyprus divided in the first place?

Depending on the narrative one's subscribed to, blame is either put on Turkey for invading the country, or Greece for instigating a coup. But despite the responsibility on both sides, the division of Cyprus actually has its roots in British colonialism.

A colony of the British Empire

Over the course of history, the island of Cyprus has seen numerous waves of conquerors come and go, including the Assyrians, the Egyptians, the Greek kingdom of Macedonia, the Byzantine Empire, and the Ottoman Empire. After over 300 years of Ottoman rule, under the Cyprus Convention, the British Empire took over administrative control of Cyprus and made it a British protectorate, although it remained under Ottoman sovereignty, according to "Nation Shapes" by Fred M. Shelley.

In 1914, Britain annexed Cyprus, and during the First World War — from 1914 to 1918 — Cyprus was used as a base for military operations. Eleven years later, Cyprus was made a formal colony of the British Empire. According to the British Ministry of Defence, the United Kingdom continues to maintain several military bases in Cyprus well into the 21st century, and they remain under the sovereignty of the United Kingdom even though the island has been independent since 1960.

Despite Cyprus's military significance in World War I, the British were never all that interested in maintaining control of Cyprus until the Cold War. In 1915, they even offered Cyprus to King Constantine of Greece in exchange for Greece joining the Allies in World War I, but King Constantine rejected the offer. However, Andreas Constandinos writes in "America, Britain and the Cyprus Crisis of 1974" that once the British were pushed out of the Suez Canal in 1956, Cyprus became "the new home of Britain's Middle East Headquarters."

Independent Cyprus

Since the 1880s, Greeks and Greek Cypriots had called for the incorporation of Cyprus into Greece, known as enosis. And after an increased British presence in 1948 following the end of the British Mandate for Palestine, the enosis movement was revived, according to "The Routledge History of Terrorism."

In "Encyclopedia of the Stateless Nations," James Minahan writes that in response to the Greek Cypriot's calls for enosis, Turkish Cypriots started calling for "taksim," meaning the partitioning of the island. After negotiations between the British, Greek Cypriots, and Turkish Cypriots failed in 1955, the Ethniki Organosis Kyprion Agoniston (EOKA), or the National Organisation of Cypriot Fighters, launched an armed campaign against the British, fighting for enosis. Considering enosis to be Greek colonialism, Turkish Cypriots created the Turk Mukavemet Teskilati (TMT), or the Turkish Resistance Association, as part of their rival national movement to resist British colonialism, according to "Writing Cyprus" by Bahriye Kemal.

The Cyprus War of Independence, also known as the Cyprus Emergency, lasted from 1955 to 1959, and during this time the island was flooded with British soldiers trying to stifle the calls for independence: The Guardian writes that many people were tortured by British soldiers. In 1959, the London and Zürich Agreements made way for the independent constitution of Cyprus, and the agreement excluded the possibility of both enosis and taksim. The United Kingdom, Greece, and Turkey all signed the independence agreement, and on August 16, 1960, Cyprus achieved independence, with governance split amongst Cypriots.

The Crisis of 1963–1964

The Republic of Cyprus was established with a power-sharing constitution, but as soon as the nation was established, tensions were seen between the Greek and Turkish Cypriots in the administration.

After a resulting deadlock in government, a constitutional court found in 1963 that Archbishop Makarios, President of Cyprus, failed to uphold the constitution in ensuring that separate municipalities were created for Turkish Cypriots, according to the Cyprus Mail.

President Makarios ignored the ruling of the constitutional court, and instead proposed 13 amendments to the constitution that would dismantle the power-sharing by Greek and Turkish Cypriots. In "Legal Aspects of the Cyprus Problem," Frank Hoffmeister writes that Makarios's 13 amendments were strikingly similar to the first stage of the Akritas plan: This was a Greek Cypriot plan, written by Interior Minister Polycarpos Yiorkadjis, that called for the removal of what were described as undesirable elements of the constitution.

Bloody Christmas

The crisis exploded due to the events that became known as Bloody Christmas. On December 21, 1963, a Turkish Cypriot couple was stopped by a Greek Cypriot police patrol for an identity check. A crowd gathered, and at least two Turkish Cypriots were killed in the subsequent shots fired by the police patrol. Subsequently, there were violent clashes across the country and on one day alone — December 24 — 31 Turkish Cypriots and five Greek Cypriots were killed, according to Cyprus Mail.

As the fighting increased and ceasefires failed, Greece, Turkey, and the United Kingdom joined the negotiations and deployed a combined 7,800 troops, known as the Joint Truce Force, to facilitate and monitor the ceasefire, per the University of Central Arkansas. Makarios also agreed to create a buffer zone that would be policed by the British. A British officer reportedly marked the buffer zone that cut through the capital city of Nicosia hurriedly with green ink, creating the Green Line.

The fighting continued into 1964 and, according to the United Nations, over 500 houses were destroyed and 2,000 were damaged in over 100 villages during the violence, mainly in Turkish Cypriot or mixed villages.

Power-sharing breaks down

As the power-sharing constitution broke down, the Turkish Cypriot political leadership withdrew and was ousted from the government. According to "Beyond a Divided Cyprus," despite this, the Supreme Court ruled in 1964 that the government was to continue to function with the constitutional deficiencies remaining.

Meanwhile, the Turkish-Cypriot leadership went into small enclaves across the country. Cyprus Mail writes that the segregation may have even worked towards creating "a paradoxical alliance between Greek and Turkish nationalisms."

As a quarter of Turkish Cypriots, up to 25,000 people, were displaced and over 500 Cypriots were killed during the wave of violence during the crisis, the United Nations deployed a peacekeeping force (UNFICYP) to the buffer zone on March 27, 1964, per the Georgetown Institute for Women, Peace and Security. As a result, the University of Central Arkansas writes that the Joint Truce Force was also disbanded. The crisis lasted until a ceasefire was finally agreed to and maintained on August 9, 1964.

The Green Line

The UNFICYP peacekeeping force was deployed by the United Nations along the Green Line that was established by the British, as well as across the island. Up to 6,500 people from various countries were deployed as part of the UN peacekeeping mission. In "The Europeanisation of Contested Statehood," George Kyris writes that as a result of the Green Line, Greek and Turkish Cypriots ended up being physically divided, and as Turkish Cypriots formed their own administrative structures due to the collapse of the inter-communal administration, they were administratively divided as well. Initially, a general committee was created with Turkish Cypriot Vice-President Kucuk at the head, as well as legislature. In 1967, this was replaced by the Provisional Administration.

In the meantime, the government of the Republic of Cyprus, which was entirely led by Greek Cypriots, began entirely ignoring the Turkish Cypriot enclaves and freezing the implementation of this law. As a result, Turkish Cypriots started relying on Turkey for political, economic, and military support.

As the Greek Cypriot government oppressed Turkish Cypriots, the Turkish government started retaliating against Greek people in Turkey. According to the American University, after economic sanctions were initiated against Turkish Cypriot enclaves, Turkey seized the property of around 8,000 Greek people living in Istanbul, and many of them were also expelled from Turkey.

Athens instigates a coup

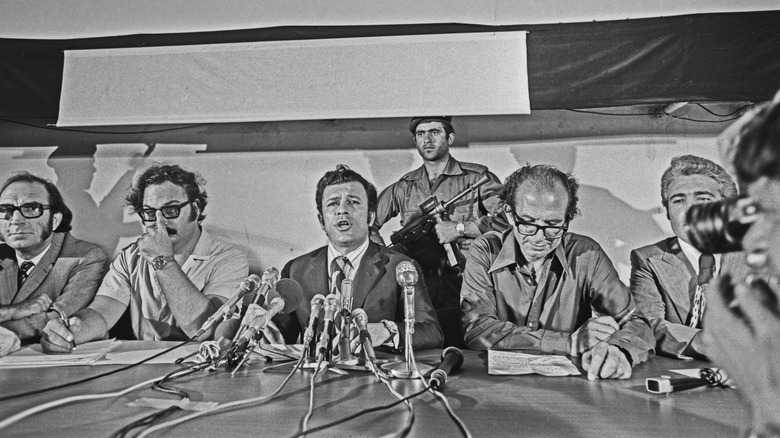

In 1967, a military coup in Greece led to a right-wing military dictatorship that would rule over Greece for the next seven years. And on July 15, 1974, the Junta carried out a coup against President Archbishop Makarios, removing him from power and replacing him with coup president Nicos Sampson. There was also a plot to assassinate Makarios, but he escaped and flew to London, England, with help from the British.

The coup was accomplished with the help of EOKA B, a far-right paramilitary organization that was created in 1971. According to Cyprus Mail, the coup was generally supported by Greek Cypriots, who showed their approval through the 15,000 telegrams of support that were sent to Sampson over the course of one week.

The University of Texas Rio Grande Valley writes that the new state was declared the Hellenic Republic of Cyprus, in an effort to establish a connection with Greece ... and alienate Turkish Cypriots. The new president Nicos Sampson was even famous for his 1969 political slogan, "Death to the Turks," and eventual annexation by Greece was also part of the coup's plan. While Turkey demanded the resignation of Sampson, Greece denied having played any part in the coup. In response, Turkey launched an invasion of Cyprus on July 20, 1974, with the support of Yugoslavia and Bulgaria.

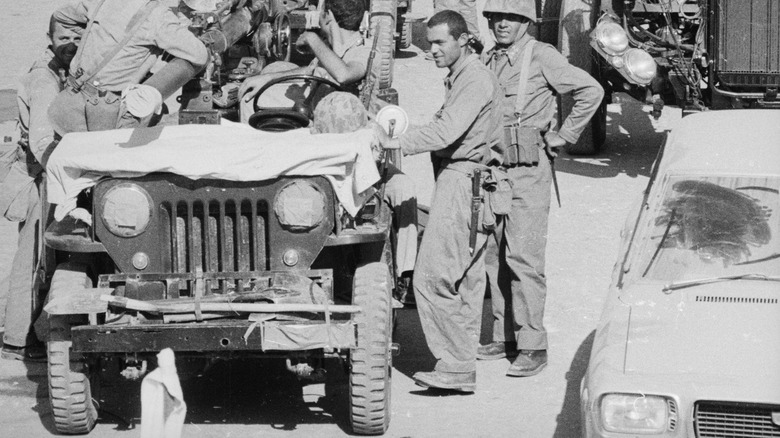

Turkish forces invade

Turkey invaded Cyprus from the northeast, five days after Sampson was installed as the head of government, in retaliation for the coup and to prevent unification with Greece. Financial Mirror writes that Turkish troops landed on the shores of Kyrenia at 5:30 in the morning, numbering over 40,000. Fighting started across the island as the Greek Cypriot National Guard and the EOKA-B mobilized against the Turkish military, Turkish Cypriot militias that guarded the enclaves, and pro-Makarios forces, according to European History Quarterly. Despite a ceasefire agreement on July 23, fighting continued and on August 14, Turkey launched a second offensive and occupied Morphou, Famagusta, and Karpasia.

Turkey insisted that the invasion was to protect the Turkish Cypriot people from attacks and annexation attempts, according to the Middle East Monitor, but after their invasion, thousands of Greek and Turkish Cypriots were killed and wounded — over 50 years later, at least 1,000 people are still considered missing. "Cyprus and Its Conflicts" writes that although the invasion technically ended by August 18, it resulted in the Turkish occupation of 38% of the island. As a result of the invasion, between 160,000 and 200,000 Greek Cypriots fled the north of the island, while up to 50,000 Turkish Cypriots fled the south.

The coup in Cyprus subsequently failed in Cyprus, and President Makarios returned to the country. The failure of the coup also brought down the junta in Greece, The New York Times reports.

A partitioned nation

With its northern half occupied by Turkey, Cyprus became a partitioned nation, and the Green Line — originally drawn by the British and guarded by the United Nations — turned into an impassable dividing line. According to "Lorenzo Milani's Culture of Peace," the barrier was also further reinforced by Turkish forces who added barbed-wire fencing, watchtowers, and minefields. The buffer zone occupies approximately 3% of the island (via GlobalSecurity.org), measuring less than 11 feet at its most narrow moment and 4.6 miles at its widest.

The northern part of the island was proclaimed to be the Turkish Federated State of Cyprus in 1975. It declared its independence and became the Turkish Republic of Cyprus in 1983, but Turkey is the only other country that recognizes it, according to the Global IDP Database. And because Turkey is the only country that recognizes it, the northern half of the country has essentially been isolated economically and politically since 1974. Al Jazeera reports that Turkey continues to maintain up to 40,000 troops in northern Cyprus, at a cost of roughly $480 million per year — subsidizing the budget also costs Turkey hundreds of millions every year.

According to Slate, border crossing points were finally opened in 2003, allowing for the possibility that Greek and Turkish Cypriots civilians may travel back and forth. In May 2014, the European Court of Human Rights also ordered Turkey to pay Cyprus over $120 million, which was to go to the relatives of those missing since the 1974 invasion.

One of the longest-running UN missions

As of 2023, the UN peacekeeping mission that continues to remain in Cyprus is one of the longest-running UN missions in history. UNMOGIP in India and Pakistan, and UNTSO in Southwest Asia, are the only other UN peacekeeping missions that were established earlier than UNFICYP, and continue to run today. The UN Security Council renews the mandate that dictates UNFICYP's presence every six months, The Daily Sabah reports, and while most of the UN peacekeeping soldiers are in the South, they also have two camps in the North. In total, there are about 750 peacekeepers and roughly 250 other UN personnel as part of the mission. According to the United Nations, the United Kingdom, Argentina, and Slovakia contribute the majority of the military.

Initially, the mandate of UNFICYP was to prevent conflict between the Greek and Turkish Cypriot communities. But after Turkey's invasion and subsequent occupation, the UN mandate was redefined towards supervising the ceasefire lines, providing humanitarian aid, and "stabilizing the situation on the island," per the Australian Department of Veterans' Affairs.

"Contemporary Social and Political Aspects of the Cyprus Problem," edited by Michalis Kontos and Jonathan Warner, writes that UNFICYP has become a "victim of its own success." Although the mission has been effective at creating stability on the island, the island remains divided with no end in sight. After 2004, UNFICYP also became the first UN peacekeeping mission to use "24-hour unattended camera surveillance to monitor a conflict zone."

The buffer zone today

Rather than disappearing, the UN Buffer Zone — otherwise known as the Green Line — is becoming a fixture of the island. Although people are able to cross at the checkpoints with their passports, the buffer zone is mostly uninhabited by people, and the only human activity it sees is UN soldiers patrolling for refugees. In addition, The Funambulist writes that the buffer zone is used by the Turkish government, Cypriot government, and even the European Union towards the weaponization of exiled people.

Cyprus Mail reports that in March 2021, the Republic of Cyprus put up its own barbed wire along the Green Line in rural Nicosia. The government claimed that this was done in order to prevent illegal migration, but many local farmers with fields along the buffer zone found their livelihoods literally cut off by the barbed wire. According to The Guardian, some asylum seekers have even ended up trapped in the buffer zone for months after the Republic of Cyprus refused to let them apply for asylum. In addition to farming fields, there are even some Cypriots living within the buffer zone: The village of Pyla sits in this isolated area, still inhabited and clinging on to the hope of future reunification, as reported by Reuters.

Phys writes that due to the lack of human activity, much of the Green Line has become a "wildlife corridor," with flourishing biodiversity. In the buffer zone, mouflon — wild sheep — can be found thriving, as well as threatened orchids, rare reptiles, and endangered mammals.