The Last Surviving Black Americans Who Were Born Into Enslavement

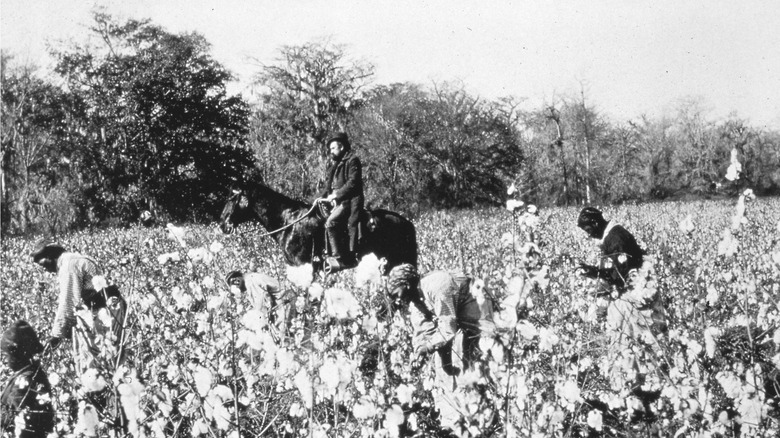

For many people, American slavery seems like a historically distant era. After all, President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation back in 1863. And Juneteenth has been celebrated since June 19, 1866, a year after federal troops announced in Galveston, Texas, that the state's more than 250,000 enslaved people were free. But those events are more than 150 years in the past. The images of Black Americans who survived enslavement live now as the faces of long-dead people staring out from old tintype photos.

Of course, the legacy of slavery still affects American society today, forcing Black Americans to deal with structural inequalities that can result in higher rates of poverty, institutional racism, police violence, and poor health, among other problems. Meanwhile, some Americans only need to trace their families a few generations back to find enslaved people among their ancestors.

What's more, those images of freed slaves in tattered old clothing aren't that far removed from us. Some formerly enslaved Americans survived well into the 20th century, including a small group of people who were born in Africa and taken to the United States in the final days of the transatlantic slave trade. Their stories are all powerful examples of endurance — and even prosperity — not just in the face of slavery, but of war, economic depression, and widespread racism.

Peter Mills

By most accounts, the very last Black American to survive enslavement was Peter Mills, who was born October 26, 1861, and died September 20, 1972, a few weeks shy of his 111th birthday. (Per the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, he died as a result of a "pedestrian accident.") Mills' extraordinarily long life encompassed his birth as a slave in Prince Georges County, Maryland, a succession of five wives, and a lifetime of manual labor.

Mills lived and worked for 109 years after the Emancipation Proclamation ostensibly freed all slaves in 1863. But some enslaved people weren't told about this extraordinary development for an agonizingly long time. Today, Juneteenth celebrations commemorate the freeing of the last known group of enslaved people in Texas — perhaps the better date for marking the full emancipation of slaves across the nation (via History). Mills was 4 years old.

According to the Fayetteville Observer, Mills spent much of life working on farms, though he often took weekend jobs digging sewers to support himself and his family. He also loved baseball, which he played whenever he could in the midst of his hardworking life.

Matilda McCrear

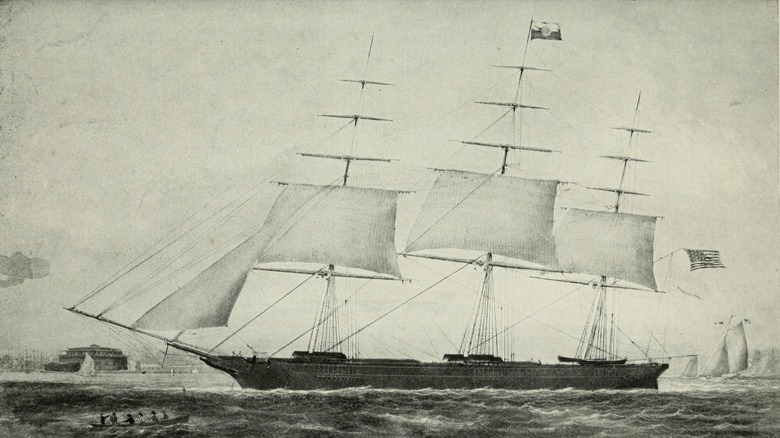

After capture and imprisonment on ships, a small but significant number of people had to then endure the brutality of a transatlantic crossing from their African homelands. According to National Museums Liverpool, African captives were already likely in poor health at the end of an arduous trip under the control of hostile enslavers. On ships, many were shackled in cramped, disease-ridden quarters below deck. Women and children were sometimes held in less-restrictive quarters, but there they often faced violence from crew members.

Matilda McCrear, as she came to be known, faced these conditions when she was just 2 years old. According to Newcastle University, she was taken in West Africa, and the ship she was on docked in Alabama in July 1860. McCrear traveled on the Clotilda, the last known slave ship to transport Africans to the United States. Smithsonian Magazine noted that a ban on the importing of African slaves had been enacted by the U.S. in 1808, yet some traders were willing to risk it for financial reward. McCrear arrived in the company of her mother, Gracie, as well as three elder sisters and her future stepfather. Two brothers remained behind in West Africa.

Though she was freed only a few years after arriving in America, Matilda faced intense discrimination in the Reconstruction-era South. She lived what was then considered an unconventional life: She had 14 children in a common-law marriage with a white man, and in her 70s she petitioned (unsuccessfully) for reparations, per Newcastle University. She died in 1940 in her early 80s.

Mary Hardway Walker

Mary Hardway Walker was born in 1848 in Alabama to enslaved parents, and she was 15 when the Emancipation Proclamation was signed by President Lincoln, according to Tennessee's Local 3 News. By the time she was 20 years old, she had already married and given birth to a child (via Mary Walker Foundation).

According to author Rita Lorraine Hubbard, who obtained a transcript of an interview that Walker gave in the 1960s, Walker worked for a large portion of her life as a sharecropper with her second husband (via Chapter 16). She also worked as a cook, cleaner, and child caretaker, as per the Mary Walker Foundation. Slaves were rarely taught to read and write — and Walker did not learn to read until she was 116 years old. In the interview, Walker was clearly wary of racist violence; she referenced "the Klux" as a reason for her reticence.

Despite that fear of reprisal, Walker joined the Chattanooga Area Literacy Movement in 1963. There, she learned to read, write, add, and subtract over the course of a year. Accolades soon followed, including the key to the city of Chattanooga and twice being deemed Chattanooga's Ambassador of Goodwill. She died in 1969 at approximately age 120. The city of Chattanooga later constructed a memorial to her and named her retirement home after her.

Anna Julia Cooper

Freedom from slavery frequently did not mean that Black Americans were granted equal rights, as per the Equal Justice Initiative. But for a lucky and determined few, education wasn't out of reach, as the life of Anna Julia Cooper illustrates. Born in North Carolina in 1858, Anna was enslaved with her mother, Hannah, according to The Archives of the Episcopal Church. Following her emancipation, Anna enrolled in a local Episcopal school, and she became so well known for her intellect that she became a paid tutor when she was only 11 years old.

Besides racial discrimination, Cooper routinely fought to take "men's" courses that were considered too laborious for women's minds. As NPR reported, she became the principal of a high school for Black students. She pushed back against an emphasis on vocational education and worked to access higher learning for her students. This put her squarely at the center of a massive debate in the Black community, as some argued that it was more useful for students to find work right away and provide for their families rather than engage in dreams of advanced degrees and artistic careers. Cooper became the subject of vicious rumors that forced her to step down. She moved to Paris, earned a Ph.D. from the Sorbonne, and returned to the very same school in Washington, D.C., as a teacher. She was also a published writer and an activist, and she continued to write and organize until her death at age 105 in 1964.

Fountain Hughes

Fountain Hughes was born around 1860, near Charlottesville, Virginia. According to Monticello, his father died in the Civil War and his mother, Mary, made her young son available for hiring for a mere dollar a month. The adult Fountain eventually found work as a gardener in Baltimore.

In a 1949 interview, Hughes claimed that his grandfather was owned by none other than Thomas Jefferson. Among his other recollections: Enslaved children didn't receive shoes until they were about 12 or 13 (before then, they went barefoot and occasionally injured themselves); and boys wore dresses until they were at least 10 years old.

As for the Civil War, Hughes had unhappy memories of Union soldiers who would take what they needed and throw away the rest, thereby denying others the benefits. After emancipation, Hughes remembered, Black people had nothing, often going homeless and facing reprisal for even attempting to read. "Dogs has got it now better than we had it when we come along," he said of the time after freedom came. He also told the interviewer that he had no fond memories of his time as human chattel. "If I thought, had any idea, that I'd ever be a slave again, I'd take a gun and just end it all right away," he said. "Because you're nothing but a dog." Hughes died in 1957 at approximately age 97.

Alfred Teen Blackburn

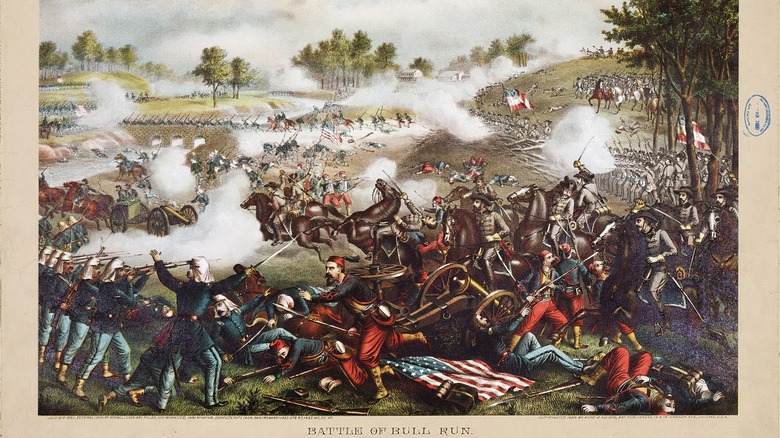

Some enslaved people in the Civil War weren't just forced to work in homes and on plantations — they were obliged to follow their "masters" to the battlefield.

According to the Virginia Museum of History & Culture, enslaved people were made to support the Confederacy by working in service of the army as laborers, cooks, laundresses, drivers, and personal servants.

Such was the situation of Alfred "Teen" Blackburn, who was born into slavery in North Carolina in 1842. Per "Historic Shallow Ford in Yadkin Valley," Blackburn went with John Augustus Blackburn to be his "body servant." Blackburn was close to the front lines of the war and saw, among others, the first Battle of Bull Run. His dangerous role did earn him a pension later in life, which supplemented a post-war and post-emancipation income as a mail carrier. With his wife, Lucy, Blackburn had 10 children. The family produced a tobacco crop for additional income that they used to help Blackburn's daughters and sons complete their educations and gain work as teachers, a police officer, and other careers.

Blackburn carried on his postal work for six decades, first completing his route on foot and later on horseback. "The Civil War and Yadkin County, North Carolina" maintained that he was the actual last surviving veteran of the Civil War. He died on December 15, 1951, age 109.

William Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson, the vice president who became president following Abraham Lincoln's 1865 assassination, owned slaves, according to the White House Historical Association. It turned out that the "Great Emancipator" and his associates certainly weren't morally pure abolitionists, as per HistoryExtra.

Despite that ambiguity, the people who were enslaved by Johnson and his family were freed by the end of the war. One of them, William Andrew Johnson, lived well into the 20th century. He was the son of Dolly, who was purchased by Johnson in 1843, and was likely fathered by Johnson's own son, Robert, as claimed in William's 1943 death certificate.

But though he was a possible grandson of the president, William didn't seem to get preferential treatment. As an adult, he recalled, his work involved getting fireplaces and wood-burning stoves going in the morning, shining Johnson's boots, and waiting on the future president at mealtimes. He would have been about 5 years old at the time. In 1863, William and his family were freed. Some became servants in the White House, where William was reportedly President Johnson's valet. Around this time, he also learned to read and write. William remained in service to the former president for the rest of the older man's life.

By the late 1930s, an interview brought attention to William Johnson, now acknowledged as likely the last surviving slave of an American president. He subsequently met with President Franklin Roosevelt, who gave Johnson an embellished cane as a gift.

Redoshi Smith

For some time, Redoshi Smith was considered to be the last survivor of the Clotilda, which in 1860 was the final ship to carry captured Africans to the United States. According to Newcastle University, she was actually outlasted by Matilda McCrear, who also arrived on the Clotilda and lived two or three years longer than Smith.

According to The New York Times, Smith was about 12 years old when she was captured in her West African birthplace and forced onto the Clotilda. Once in the United States, she was called Sally Smith and was married off to an older man. Freed five years after her arrival in North America, she chose to stay in Alabama with the Smith family, who had previously claimed to own her. She told an interviewer that she and other former slaves believed that this was their safest option. She died in 1937 at approximately age 89.

As the journal Slavery & Abolition notes, the details of Redoshi Smith's life are scattered across quite a few different accounts, including previously unpublished work by author Zora Neale Hurston. Some of those accounts question Smith's words, noting that her life in post-war Alabama would have been marked by rampant poverty and racist violence. It's possible that Redoshi's sunny portrait of the Smiths was a fiction presented to a white interviewer. She was also seen in a 1938 documentary, making her one of the only women known to have been filmed as a survivor of the transatlantic slave trade.

Oluale Kossola

Though he often went by the name Cudjo Lewis, the old man who spoke to Zora Neale Hurston for her book "Barracoon: The Story of the Last 'Black Cargo'" was not born with that name. According to History, he was actually Oluale Kossola, a Yoruba man who was stolen from his West African village when he was 19 years old.

He was forced onto the ship Clotilda, which docked secretly at night in Alabama because traders were breaking a decades-old law banning the importation of African slaves. Kossola was pushed into work on a plantation where he didn't understand the language and was profoundly isolated.

Union soldiers who passed through the area in 1865 told Kossola that he and the other slaves were free, but he was never compensated for his years as a slave. With his wife, Abile, Kossola attempted to raise money to return to Africa, but was unsuccessful. They stayed near Mobile and raised six children together, all of whom had Yoruba names. He and other freed people banded together to purchase land and established a settlement known as Africatown. There, he died in 1935, aged 94 or 95 (via Encyclopedia of Alabama).

Kossola's story, though, had a difficult road ahead. According to Vulture, Hurston encountered many roadblocks in her quest to publish "Barracoon" — including requests to get rid of the transcribed dialect of its subjects, and concerns that its account of African participation in the slave trade would damage the reputation of Black Americans already facing serious racism. It wasn't published until 2018.

Delia Garlic

While some Black Americans couched their recollections of slavery in ways that softened their experiences, and the reputations of slave owners, Delia Garlic was not among them. "Them days was hell," she told an interviewer in 1937 (via Library of Congress).

According to Enslaved: Peoples of the Historical Slave Trade, Garlic claimed to be about 100 years old when she spoke to a representative of the Federal Writers' Project. Her tragic story began when she was taken from most of her family not long after her birth in Powhatan, Virginia. The infant Delia and her mother were sold to a sheriff, and her brother William was taken elsewhere and never seen by them again. Garlic made clear to the interviewer that many decades later, the trauma of that separation was indelible. She also experienced considerable abuse, ranging from backbreaking work made worse by little nutrition to serious beatings.

Garlic's first husband disappeared after he was forced to work with Confederate soldiers at the beginning of the Civil War. Her second husband was Miles Garlic, and after the war she moved to Alabama. The 1937 interview took place during the Great Depression, but Garlic claimed that her decades in servitude meant that those final years were the happiest of her life.