What Life Was Like For Black People During The Civil War

History classes have a way of metabolizing the lives of Black people during the Civil War into simple, neat categories. We learned that Black people in the North were free and educated, while Black people in the South were enslaved under horrific conditions, and that abolitionists were the sole group working toward liberation. Of course, the reality is much more complicated.

We think of President Abraham Lincoln as the "Great Emancipator." In truth, Lincoln's prime focus was preserving the Union, and ending slavery was mostly a political strategy for him. The accepted narrative erases the active role Black Americans had in their own liberation during the Civil War — forging the economy forward, disseminating information, acting as spies, and fighting fiercely in combat.

"Our lofty notions of democracy, egalitarianism, and individual freedom were articulated by the Founders," Ta-Nehisi Coates writes in The Atlantic. "But they were consecrated by the thousands of slaves fleeing to Union lines, some of them later returning to the land of their birth as nurses and soldiers." This is the story of the lives of Black people during the Civil War, who were far from the sidelines and whose sacrifices, vision, and labor profoundly impacted the war effort.

The Civil War was fought over Black liberation

In 1857, the Supreme Court's Dred Scott v. Sandford decision had sent a powerful message to Black people in America: Living there, working the land, and gaining freedom still wouldn't guarantee citizenship or rights. This ruling had come on the tail end of a series of foreboding laws. The Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 had incentivized the capture of self-emancipated black people, and courts had ruled that Congress did not have the power to abolish slavery in new US territories.

While some revisionists may say that the Civil War was fought over states' rights or the preservation of the Union, historians largely agree that this war was, no matter how you slice it, about the status and freedom of Black people. In March 1861, Alexander H. Stevens, the vice president of the Confederate States of America, put it baldly: "our peculiar institution African slavery as it exists among us [...] was the immediate cause of the late rupture and present revolution," according to the National Park Service. After Abraham Lincoln won the 1860 election and seven Southern states seceded, the United States fractured into war. Though Lincoln insisted his aim was to keep the Union together, emancipation was the true goal of the war for both enslaved and free Black people in America.

The lives of free Black people during the Civil War

In 1860, there were a total of 488,070 free Black people in the US. That's about ten percent of the total Black population, per Henry Louis Gates Jr.'s research. It may come as a surprise, but just over half of all free Black people lived in the South and stayed there during the Civil War. This population was comprised of free Black people who had been living in the Louisiana territory, immigrants from the West Indies, the formerly enslaved who had aged or purchased their freedom, and those who had been emancipated in the feverish aftermath of the American Revolution.

However, being free did not mean being a citizen. Many free Black people lived in cities and were relegated to jobs that white people didn't want: blacksmiths, barbers, maids, and carpenters, as The Root reports. Free Black people who lived in Confederate states could not hold office or testify in court and were required to carry ID proving their free status. They were denied government war relief aid, so they went hungry and lacked medicine, according to Encyclopedia Virginia. In the North, where slavery had been outlawed since the Missouri Compromise, free Black people had more access to education, but they were also degraded and segregated and sometimes endured separation from their family. Due to differences in treatment, there is no monolithic experience of free Black people during the Civil War. That said, they largely supported Union efforts.

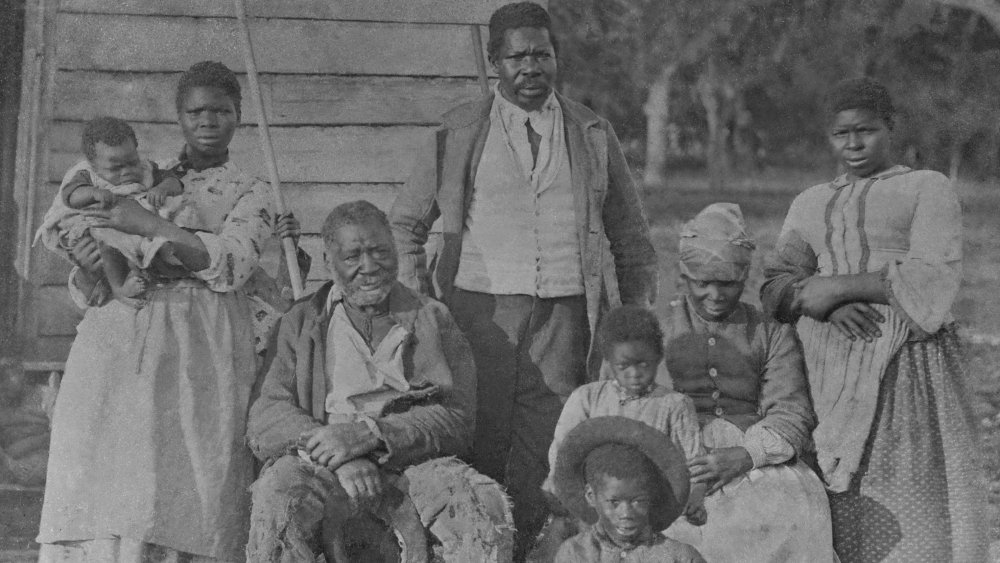

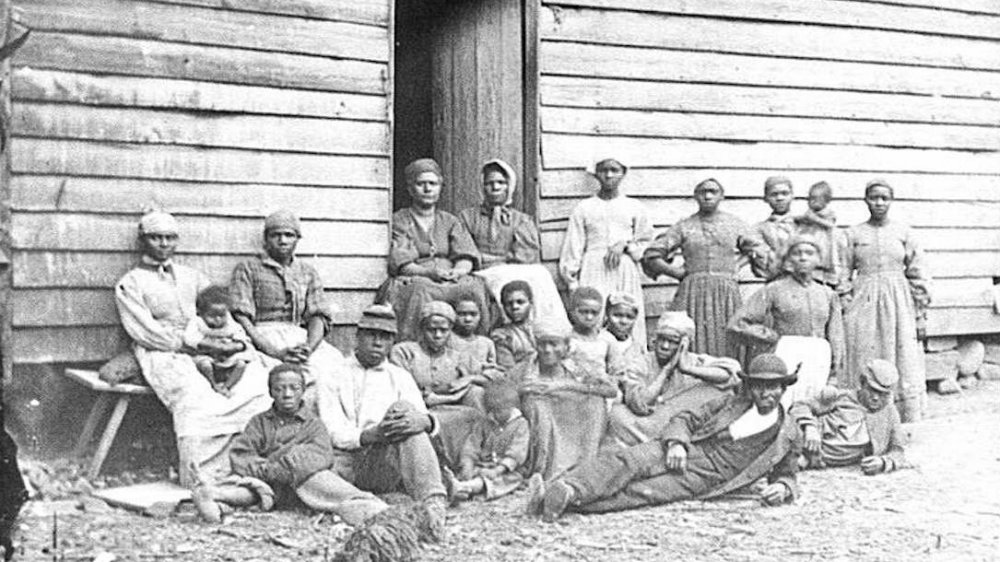

The lives of enslaved Black people during the Civil War

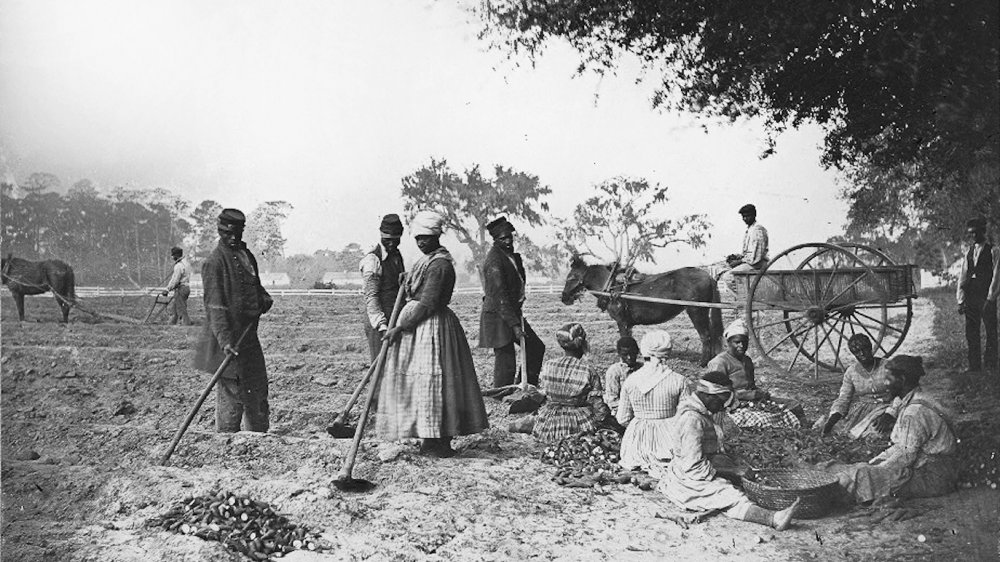

The labor of enslaved Black people was the entire basis of the Southern economy before and during the Civil War. According to History, the Mississippi River Valley had more millionaires per capita than any other place in the nation due to the immense wealth that Black labor brought white enslavers. So, it makes sense that said labor was central to the Confederate war effort, with the onus of agricultural production and field labor to feed civilians and soldiers put on Black people.

Through Confederate impressment policies, many enslaved people were forced to work in iron factories, as nurses and cooks in army hospitals, or made to build fortifications and trenches for the Confederate Army up until the end of the war. With enslaved Black men fulfilling more industrial roles, female enslaved workers took on the added labor of cultivating wheat, corn, and cash crops.

With many white enslavers away at war, the use of slave patrols flattened, and those enslaved on plantations experienced less violent discipline and more independence. Meanwhile, per Encyclopedia Virginia, there was still some pushback, as the Confederacy constantly feared slave rebellions: Industrial slave-hiring systems became rigid, and some of Virginia's churches denied slaves the right to join without their enslaver's permission. During the Civil War, the prices and demand for slaves climbed, leading to family separation. With enslaved men being impressed to work in Confederate camps, many women and children were left behind.

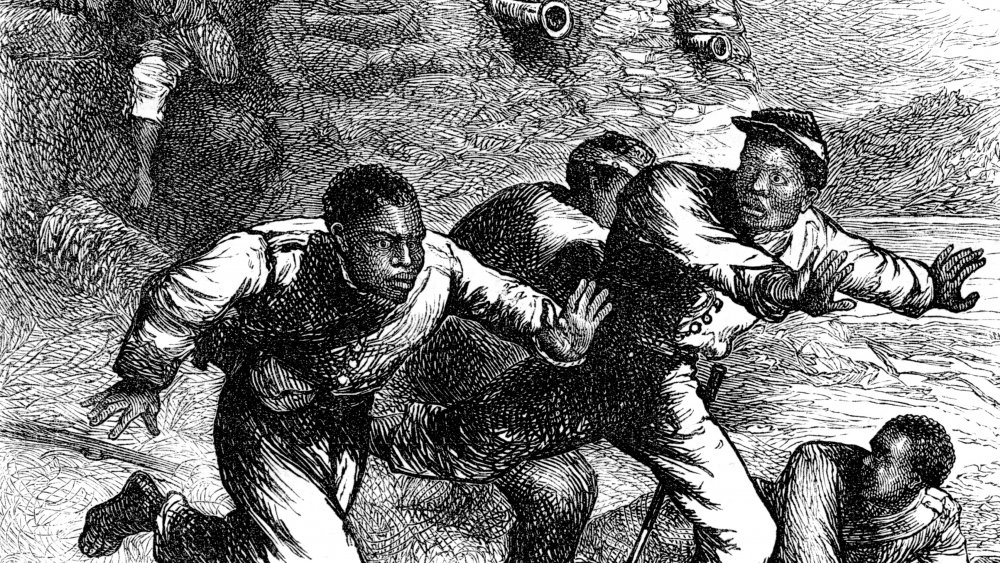

Escaping with the Union Army

It's important to remember that the abolishment of slavery was not the goal of the war for President Abraham Lincoln, but the haze of war still proved to be an opportunity for many to escape from bondage. Before the Emancipation Proclamation of 1863, enslaved Black people in the South would often trail along with Union armies that were invading local towns. This practice first started in 1861, when General Benjamin Franklin Butler, commanding Fort Monroe in Virginia, wanted to offer safety to three slaves who had turned up at the fort, per PBS. Butler decided these enslaved people were "contraband of war," as they were property in the eyes of the South (as disturbing as that is). While they were called "contraband," essentially, the Union was offering the chance of freedom for the self-emancipated under an armed military.

Because escaped slaves had familiarity with the terrain and the people, these Black spies, called "Black Dispatches" were extremely valuable for collecting intel about the Confederacy. Confederate general Robert E. Lee even once admitted that Black spies were the "chief source of information to the enemy," as told by HistoryNet.

In 1861, the Union passed the Confiscation Act, making it legal to confiscate enslaved people from the Confederate states, and the next year, the Union prohibited the returning of any enslaved people. It was the first step toward widespread emancipation.

Refugee camps in the Civil War

How did the enslaved population of America transition from being Union Army "contraband" to having their own freedom? An estimated 200 Union refugee camps were set up during the Civil War and saw up to 800,000 enslaved or formerly enslaved Black people pass through them. They were mostly located in the Deep South, stretching from New Orleans to St. Louis, according to research by Abigail Cooper at BrandeisNow. For some formerly enslaved individuals, like the liberated Mary Armstrong, returning to a refugee camp and risking possible capture was the only way to try to reconnect with family who had been torn apart by slavery.

The living conditions in these fabric tent camps, which housed up to a few thousand people, were poor and disease-ridden, and food was often rationed. Amid the backdrop of war, refugees lived in fear of raids from the Confederacy. A camp called Slabtown, now the site of Hampton University in Virginia, was robbed and burned down by the Confederate Army. However, despite the conditions and precarious safety, it was here for the first time that former slaves came together. Kidnapped from disparate cultures, the refugees united to set up schools, exchange ideas, and learn rituals, and for some, the promise of freedom led to religious revivalism. It was in these camps that many Black Americans first celebrated their Emancipation Jubilee on January 1, 1863.

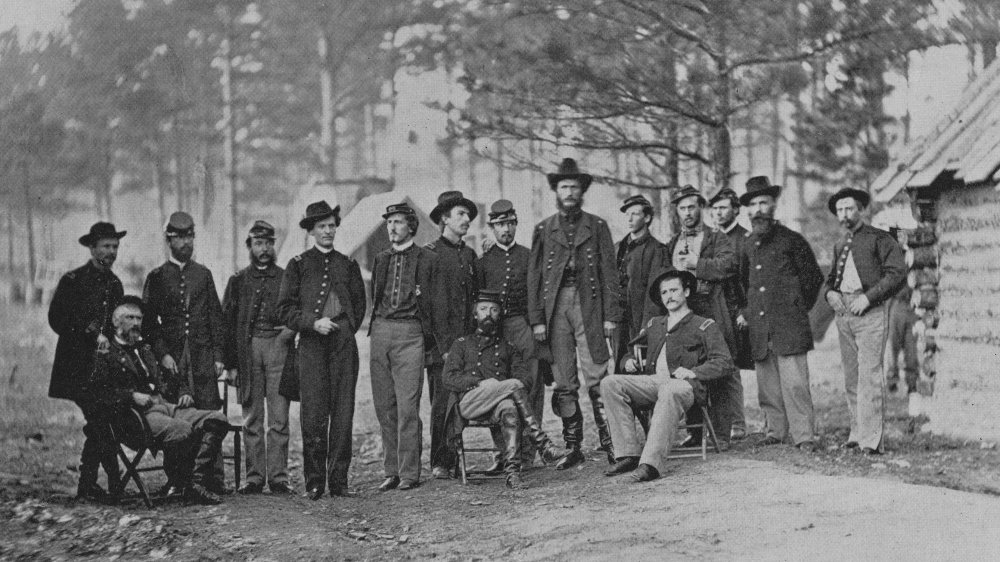

Black soldiers were initially unwelcome in the Civil War

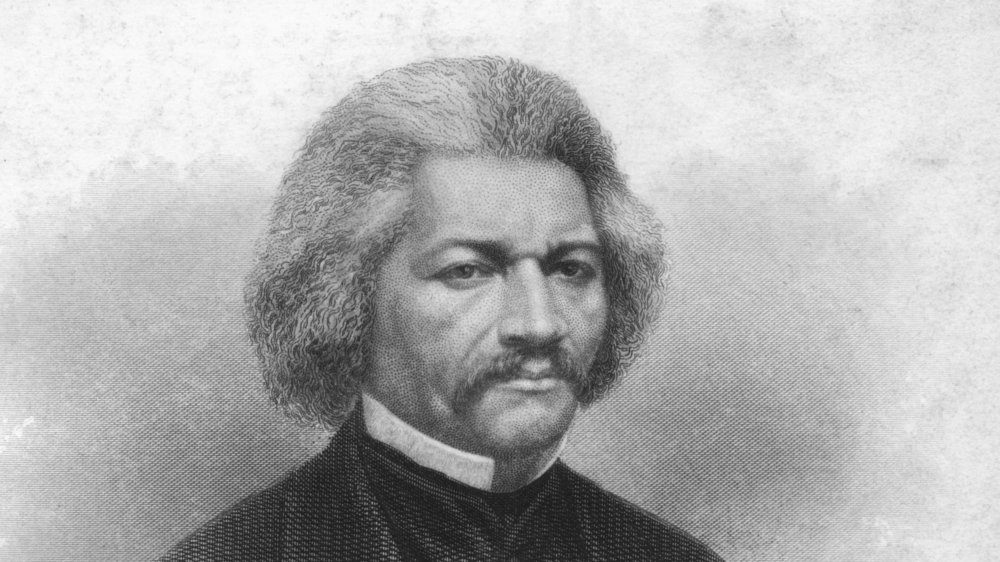

The story of how 180,000 Black Americans got to the battlefield isn't so straightforward. At the beginning of the Civil War, there was a federal law banning Black people from enlisting in the Army dating all the way back to 1792. Abolitionist and orator Frederick Douglass pushed President Lincoln to reconsider the ways Black Americans could contribute, telling Lincoln, "We are ready and would go," according to the Constitutional Rights Foundation. A far cry from the free North we might have pictured, many white Americans still held racist beliefs about Black people being mentally inferior and thought they could never train as soldiers.

President Lincoln's reluctance to integrate the Union Army stemmed from the fear that doing so would cause border states, like Missouri, to also secede. Douglass saw Black participation in the Union not as a strategy but as a pathway. "Once let the black man get upon his person the brass letters U.S., let him get an eagle on his button, and a musket on his shoulder and bullets in his pockets, and there is no power on earth which can deny that he has earned the right of citizenship in the United States," Douglass explained, per the Library of Congress.

Black militias switch sides

In 1862, the Union Army captured New Orleans and occupied it under the command of Major General Benjamin Butler. At the time, the Confederate Army had allowed a militia of free Black men, commanded by Black officers, to form in Louisiana, as told by the Constitutional Rights Foundation.

One important thing to remember is that by 1862, the Confederacy was impressing free Black people in their territory to serve their army, largely through manual labor. So, a free Black person working under the Confederate flag didn't necessarily mean they sympathized with the cause. That much was true for the Louisiana militia, which came to Butler and asked to switch sides. Butler transformed this militia into the First Regiment Native Louisiana Guards and kept the Black captains and lieutenants in their positions of power. General Butler formed two more all-Black militias, this time under white command. Though unsanctioned by the government, these militias were the first-ever Black troops in the Union Army.

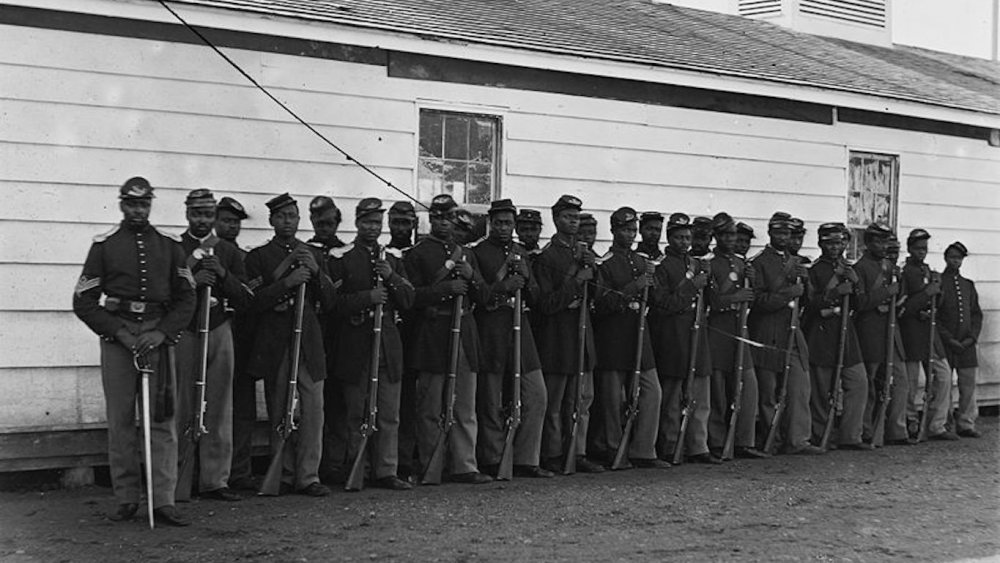

Black soldiers become legal

By the summer of 1862, with no end to the war in sight, President Abraham Lincoln reassessed his position on Black soldiers. According to History, the number of white volunteers was shrinking, and the Union needed manpower. In July 1862, Congress passed the Second Confiscation and Militia Act, which granted Lincoln the right to employ Black people for the war effort in whatever capacity he saw fit. Black infantry units sprang up — the First Kansas Colored Infantry, the First South Carolina Infantry, and the Louisiana Native Guards — and took on their first expeditions.

Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, and declared all enslaved people residing in Confederate states free. It was only then that the War Department began to actively recruit free Black people under the Bureau of Colored Troops. All were to be led by white officers, per the Constitutional Rights Foundation. Black leaders at the time, such as William Wells Brown, Martin Delany, and Frederick Douglass, spread the word to recruit Black troops, as told by Britannica.

In the spring of 1863, the 54th Massachusetts Infantry, made up of 1,000 Black soldiers and commanded by Robert Gould Shaw, became the first regiment from the North. On July 18, the 54th led an assault on Fort Wagner, which guarded the Confederate-held Charleston port. During this charge, the 54th lost about 40 percent of its men. Still, the story of the courageous assault helped push the acceptance of Black people in the Army.

Harriet Tubman's band of spies

You probably know Harriet Tubman as the conductor of the Underground Railroad, but this iconic abolitionist was also a nurse, cook, and spy for the Union Army. A pro at navigating the South, Tubman gathered a group of liberated men to act as spies and gather information about rebel camps, per America's Library.

In 1863, Harriet Tubman, Colonel James Montgomery, and 150 Black soldiers went on a gunboat raid in South Carolina along the Combahee River. They had the express purpose of freeing enslaved people, recruiting Union troops, and destroying rice plantations. The Union Army set fire to local plantations. Initially, the enslaved Black people hid in the woods during the raid, but once they realized who was behind it, they came running toward them with their belongings in hand. "I never saw such a sight," Tubman recalled. Because many of the escaping enslaved people spoke the Gullah dialect and Tubman did not, she sang a popular abolitionist song to calm them.

In what would become known as the Combahee Ferry Raid, over 700 enslaved individuals were able to escape with the gunboats. Tubman was the first woman in the United States to lead an armed military operation, as History reports. In July 1863, the Boston newspaper Commonwealth picked up the story of the heroic Black woman-led raid and named Harriet Tubman as the mastermind. However, despite petitions, she was denied pay for her work as a soldier.

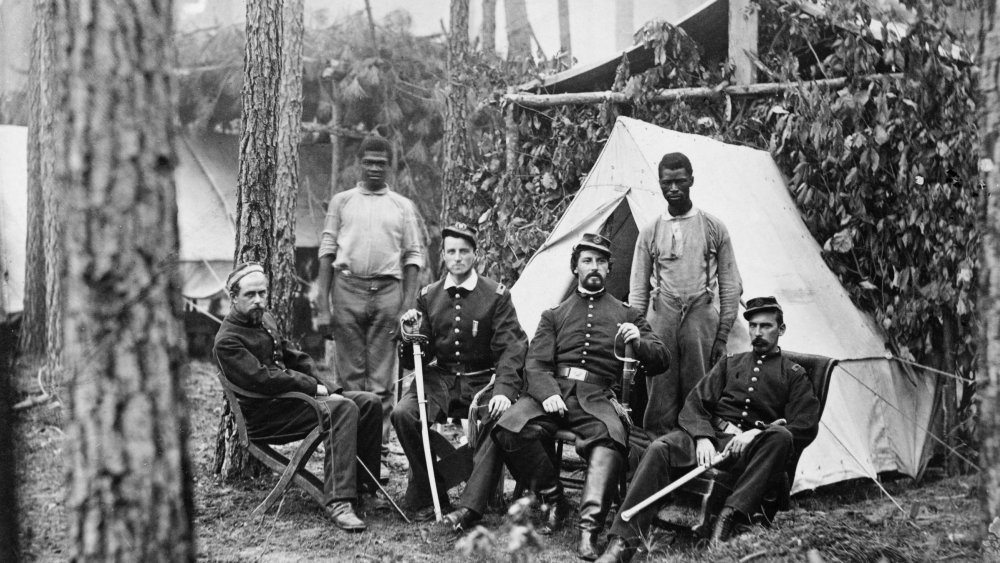

A sacrifice with unequal treatment

By 1865, an estimated 180,000 Black soldiers served in the Union Army, making up about ten percent of the total army. The State Historical Society of Iowa notes that the United States lost 40,000 Black soldiers throughout the war, 10,000 in battle and 30,000 from illness or infection. Even as Black people were sacrificing their lives in the Civil War, they were by no means treated equally, or frankly always well, in their service.

Black soldiers were often given the most difficult and dirty jobs on the battlefield, like digging trenches, given poor-quality equipment, and didn't receive adequate medical care. Black people who enlisted in the Union Army received $10 a month, which was $3 less than white soldiers, according to the Constitutional Rights Foundation. It wasn't until 1864, after much conflict, that Black soldiers finally gained equal pay.

In the event that Black Union soldiers were captured by the Confederates, they risked being enslaved or hanged. On April 12, 1864, at Fort Pillow, Union troops surrendered in battle to Confederates commanded under General Nathan Bedford Forrest. However, instead of taking the Black soldiers as prisoners of war, the Confederates gunned them down. On that day, known as the Fort Pillow Massacre, 300 Black lives were lost. This horrendous event caused the Union to eliminate future prisoner of war exchanges with the Confederates. Throughout the Civil War and the 449 battles that Black people fought in, their ranks remained segregated from whites.

The truth about Black Confederates

It has been claimed that anywhere from 500 to 100,000 free or enslaved Black people served the Confederate Army during the Civil War. However, this skews the fact that the majority were enslaved servants attending to their enlisted enslavers. Author Kevin Levin described Black Confederates as "the most persistent myth" about the Civil War to The Guardian.

Within the army, enslaved Black people endured harsh conditions as on a plantation. The Confederacy did not allow Black men to serve in combat, so instead, they were laborers, teamsters, and cooks in army camps, according to the American Battlefield Trust. In fact, the forced labor expanded to free Black people, who were impressed by the Confederacy in 1862. No Black Confederate combat units existed, despite the photographs of armed Black Confederates. No documentation exists of a Black man being paid by the Confederate Army as a soldier. It was only on March 4, 1865, not long before the end of the war, that the Confederate Congress voted to allow to arm Black people for their cause, per Encyclopedia Virginia.

Motivations for participating were particularly complicated for enslaved Black people in the South. Some enslaved black servants attended Confederate reunions after the war and stayed in contact with their enslavers for financial reasons. Still, it is essential to note that there is no primary source from a Confederate soldier that ever makes a comment about serving with a Black soldier.

The aftermath of the Civil War

On December 6, 1865, the United States adopted the 13th Amendment, outlawing slavery. The 14th Amendment granted Black people citizenship in 1868. Black men wouldn't gain the right to vote until 1870 with the 15th Amendment. However, the conclusion of the Civil War was not a magic wand that fixed the institutional racism the United States was built on. The Reconstruction period, from 1865 to 1877, saw a surge of white supremacist ideology, "black codes" which limited work opportunities and pay, and the rise of terrorist groups like the Ku Klux Klan, according to Britannica.

Black Americans in the South struggled under Jim Crow laws and the economic limitations of sharecropping, while Black people in the North competed for industrial jobs. At the same time, there was a powerful emergence of Black-led churches and Black-led colleges like Fisk University and the Hampton Institute. By 1901, 20 Black representatives and two senators were elected to Congress.

Though it had imperfect results, the Civil War was a revolution for Black lives in the United States. Major Martin Delany, a high-ranking Black officer, told a crowd in 1865, "Do you know that if it was not for the black men this war never would have been brought to a close with success to the Union, and the liberty of your race, if it had not been for the Negro?" per the National Park Service.