These Were Hitler's Plans For The U.S. If He'd Won WWII

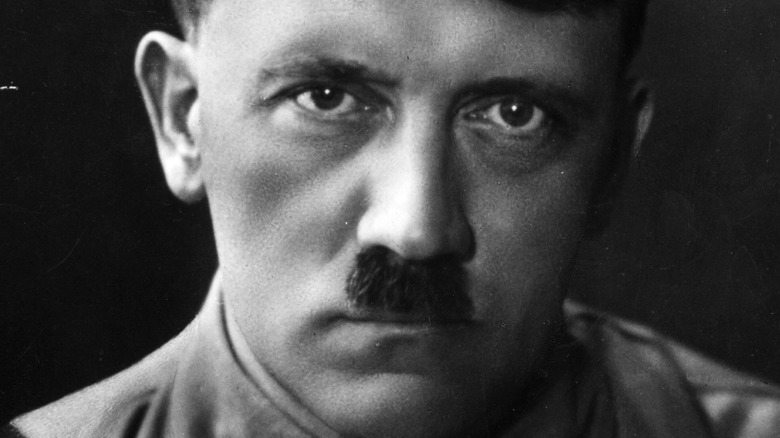

History isn't linear: It's more like a spiderweb than a progression of singular events through Points A, B, C, and so on. Take World War II. For a long time, historians have been trying to learn just how much America knew about what was going on in Nazi Germany, and a U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum project to document newspaper headlines of the era — and going back to the 1930s — makes it pretty clear that there were enough warning signs that "Why didn't the U.S. get involved sooner?" becomes an uncomfortable question.

Every history class teaches that it was the attack on Pearl Harbor that finally got the U.S. involved, but here's the thing: Hitler and Nazi Germany declared war on the States before the U.S. government could issue their declaration. Hitler's play came four days after the attack on American soil, and as The Wall Street Journal explains, it came amid opinions vastly underestimating what the U.S. — relatively fresh out of the Great Depression — was capable of.

Why Hitler thought it was a good idea to kick the sleeping giant that was the U.S. is complicated, but let's look ahead a bit. He's not really known for his forward-thinking and his planning ahead, but surely, there must have been some plans in place for a Nazi victory ... right? What, exactly, did Hitler plan to do with the U.S. if he happened to win? That, too, is complicated.

How much of a plan was there?

History is very clear about Hitler's relentless march across Europe and his desire to rebuild under the flag of the Third Reich. But what about across the Atlantic? James P. Duffy, historian and author of "Target America: Hitler's Plan to Attack the United States," says that's a little less clear, and historians have long debated how much Hitler wanted.

Duffy says that the most likely answer is that Hitler intended to rule the world. He cites a 1927 letter from Rudolf Hess to the London-based Nazi Walter Hewel, in which Hess wrote of Hitler preaching: "[world peace] will be realizable only when one power, the racially best power, has attained complete and uncontested supremacy. That [power] can then provide a sort of world police," which seems to confirm there were plans for even America to fall under the jurisdiction of a global Nazi law enforcement agency.

Hitler definitely had his eye on the U.S.: Although The National Interest calls the Nazi attempt at building a bomber that could cross the Atlantic an idiotic waste of resources, the idea behind building something literally called the Amerikabomber means that the U.S. was on the sort of list that no one wants to be on. And that, says Duffy, was just part of it. In 1941, the Nazi regime started planning for a postwar world. First and foremost, that meant a massive navy with hundreds of submarines, anchored by 25 battleships and 150 destroyers.

Hitler officially told LIFE that the U.S. had nothing to worry about

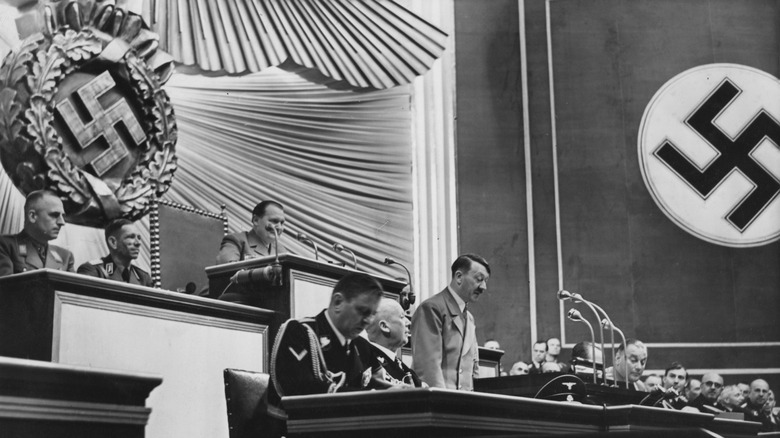

In the spring of 1941, LIFE magazine sent correspondent and former Belgian ambassador John Cudahy to report on what was happening in Germany. Cudahy got a sit-down with Adolf Hitler himself, who started by pointing out that convoys — just like the ones that the U.S. was sending to Britain — signified war.

So Cudahy got right to the point and asked Hitler what his plans were regarding the U.S. He explained that people were worried and that most Americans backed the idea of going to war against Nazi Germany because they were afraid that once Europe fell, they'd be next. Hitler — who was speaking through a translator — said that idea was a preposterous one. Cudahy wrote: "He laughed at that and refused to take me seriously. He said the idea of a Western Hemisphere invasion was about as fantastic as an invasion of the moon." Hitler also went on to say that he couldn't believe Americans thought that: "he had too high an opinion of the intelligence and good sense of Americans," Cudahy wrote.

What was the reasoning? The logistics just didn't work out. Millions of troops would need to be moved all the way across the Atlantic for the Nazis to gain a foothold in the U.S., and that meant there was absolutely nothing for America to worry about. Hitler said so, but rational thought and reasoning weren't high on his skill list.

The U.S. worried about a Nazi victory crushing the global economy

When LIFE magazine's John Cudahy spoke with Adolf Hitler in 1941, he asked about another worry America had regarding a Nazi victory. Even if the Nazis didn't sweep across the North American continent like they did the European one, there was still the possibility that they would dominate the global economy to the outright destruction of everyone else. Why? Cudahy explained — rather politely — that "a lower standard of living for workers in Germany and disciplinary methods imposed on German labor" would mean German output under the Nazi regime would be sky-high, profits would also be through the roof, and no one else would be able to compete.

Hitler said that there was nothing for the U.S. to worry about there, either, because not only did he have every intention of improving the lives and working conditions of the everyday German once the pesky war was over, but his vision for international trade post-war was one built on trading goods for goods.

His example was the agricultural states of the Balkans trading for the industrial- and commercially-produced goods of Germany, and it just wouldn't be worth America's time to try to ship all their products over to Europe. America wouldn't even be impacted, and to sum up how much credence should be put into any of that, he also remarked, "We shall settle relations with our neighbors in such a way that all will enjoy peace and prosperity."

For Hitler, the U.S. was an inconsequential part of WWII

In order to talk about what Hitler might have had in store for the U.S., it's worth mentioning just why he might want to see that part of the world burn — at least, eventually. According to University of North Carolina emeritus professor of history Gerhard L. Weinberg (via the History News Network), Hitler had been writing about taking out the U.S. as far back as the 1920s. While he wanted global domination for Germany and all that, he also felt like it was sort of his moral obligation to right a (perceived) wrong — and that skewed his view on war with the U.S.

It all went back to the stab-in-the-back myth, which the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum describes as the belief that German's loss in World War I came not on the battlefield, but because of espionage, sabotage, and subterfuge on the home front. All that was, of course, supposedly led by those who would become enemies of the Nazi state, including Jews, liberals, and communists.

At the same time, it meant that America didn't really have all that much to do with Germany's loss. Therefore, America wasn't a military might that needed to be contended with, but what historian and author James P. Duffy says was described as "Europe's greatest future rival," (via "Target America.") And that meant Hitler believed he could wrap up the war in Europe, take his sweet time building up a navy, and then deal with the U.S.

Hitler wrote of a third war — separate from WWII — to deal with the U.S.

Adolf Hitler famously wrote "Mein Kampf," but less famously, he wrote a second book, too, the very directly-named "Hitlers Zweites Buch," or "Hitler's Second Book." According to "Target America: Hitler's Plan to Attack the United States," the book was written in 1928 but not published until 1961. It outlined a series of three conflicts, and it wasn't until the third one that Hitler got around to the U.S.

First, Hitler saw his Germany taking on France to regain what they had lost post-WWI. Then, he was going to head east and seize all the land — and agricultural resources — he needed from the Soviet Union. And then? On to America, which he wrote was a "real threat to German domination of the world."

But here's the thing: Hitler wrote that analysis before the Great Depression got into full swing, and as he watched what was unfolding across the Atlantic, he eventually came to the conclusion that America was so weakened by her own problems that it didn't really matter. The third war could wait: According to University of North Carolina emeritus professor of history Gerhard L. Weinberg (via the History News Network), Hitler believed that wrapping up the war in Europe, stabilizing his Third Reich, and building up an army of long-range forces was all something he could take his time doing. America, he thought, was too weak to do anything but wait.

He viewed the U.S. as a potential best friend

There's a lot that's been written about Adolf Hitler's obsession with taking on the Soviet Union, but according to Cambridge historian Brendan Simms, he was just as obsessed with the U.S. So much so, Simms told ExBerliner, that it shaped policies across the Third Reich. Simms explains that the more research he did, the more he found about Hitler's focus on America: "It became absolutely obvious that 'Anglo-America' — that's my phrase, Hitler tended to refer to them as the 'Anglo-Saxons' — was the biggest kid on the block, his main focus, his main enemy, the partner he would have liked. The biggest element of his reality."

That's a massive claim, and Simms says that there are a few layers to Hitler casting his greedy eye toward the U.S. Part of that started with the U.S. having something that Germany didn't: Size. Let's put that in perspective (with help from Maps of World). The U.S. is about 28 times the size of Germany, but that only tells part of the story. Germany could fit inside California and take up about only 85% of the state. It's also about the same size as Montana and New Mexico, give or take a bit.

Even if Hitler had managed to take over all of Europe, building his master race would require a ton of space and a ton of resources — which America had in abundance.

Hitler thought the U.S. contained valuable blood for his Aryan race

Adolf Hitler was front and center at WWI's Second Battle of the Marne, and according to Cambridge historian Brendan Simms (via ExBerliner), it was there that he had a run-in with two American soldiers, and they made a massive impression: They were tall, blond-haired, and blue-eyed. Sound familiar?

Hitler's attempts at building his master Aryan race are well documented, and Simms says there's another, oft-overlooked part of that. Hitler developed a theory that one of the richest places to find all that Aryan DNA he was so obsessed with was the U.S.A. — and conquering America meant all new seeds from which his Aryan race could grow.

The theory went like this: Over the course of hundreds of years, the U.S. population had been reinforced by immigrants from Europe. They weren't just any immigrants, either — they were the brightest, the strongest, the most adventurous, and the most resilient. They left behind a Europe that was overcrowded, disease-ridden, and famished, headed west, and settled in the U.S. There, they thrived with wide open spaces, and resources of the type only America could offer. And United States laws helped reinforce his ideas about just how pure their blood was: Legislation limited or outlawed immigration from certain areas of Europe — like the Slavic countries — along with interracial marriages. In other words? He saw the U.S. as an invaluable source of genetic material.

Hitler tapped Henry Ford for great things

Henry Ford is often lauded as the father of the American automobile industry, but here's the thing: While he was a genius when it came to industry and manufacturing, he was a terrible person. Ford was a raging antisemite, and PBS says that he was often quoted as saying that all the world's ills could be traced back to "Jews or to the Jewish capitalists," and if that's the sort of thing that seems like it would have Hitler singing, "You've got a friend in me," it absolutely was. And according to Bradley W. Hart, author of "Hitler's American Friends" (via The History Reader), it was even more than that. Ford was spouting antisemitic rhetoric long before mainstream America knew about things like the concentration camps, and his views didn't go unnoticed by Hitler.

According to research from The Nation, Ford profited heavily from manufacturing for the Third Reich — even for months after the U.S. officially declared war. A contemporary report from the U.S. Treasury Department showed they knew about it, summed up in this observation: "There would seem to be at least a tacit acceptance by [Ford's son] Mr. Edsel Ford of the reliance ... on the known neutrality of the Ford family as a basis of receipt of favors from the German Reich."

Hart says further that Hitler actually saw Ford as a way into America, and he uncovered records describing how Hitler had tapped "'Heinrich Ford' [to] become 'the leader of the growing Fascist movement in America.'"

Hitler had little use for the American Nazis of the time

World War II usually plays out as an Allies vs. Axis conflict, but it wasn't that neat and tidy. The U.S., says The National WWII Museum, had a faction of Nazis that weren't just alive and well, they were holding rallies at venues like Madison Square Garden. The German-American Bund dated back to 1936, and the entire idea behind the organization was to promote all the ideals and racial hatred that went along with being a Nazi. That Madison Square Garden event attracted about 22,000 loyal members (in 1939), and it was done under the command of a German WWI veteran named Fritz Kuhn.

The Bund, of course, got the attention of The House Committee on Un-American Activities, and while they were found not to be a threat to national security, there is an interesting footnote. One of the claims used to discredit the Bund was that Kuhn reported directly to Hitler and that Hitler was meddling in U.S. affairs.

It makes sense that Hitler would be thrilled to have a Nazi party ready and waiting for him, but not only was it not true, but according to Traces, Hitler outright denounced the party. Why? The Nazis thought the Bund was giving them a bad name.

A book recovered from Hitler's personal library hints at a terrifying possibility

Names like Dachau and Auschwitz are instantly recognizable, but they made up only a sliver of a percentage of the facilities the Nazi regime built to contain, enslave, and execute those they didn't like. Here's a terrifying statistic: According to the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, there were more than 44,000 camps of varying purposes — all detention and incarceration-based — that were active during the Third Reich.

Would those camps have been set up in North America? According to the CBC, probably. In 2019, the Library and Archives Canada purchased a book that had been taken from Hitler's personal library. It was called "Statistik, Presse unf Organisationen des Judentums in den Vereinigten Staaten und Kanada," which translates to, "Statistics, Press, and Organizations of Jewry in the United States and Canada." The 137-page book is essentially a compilation of data on Jewish populations across North America, and as the LAC curator Michael Kent explained, "This information would have been the building blocks to rolling out the Final Solution in Canada."

The book — written by Nazi linguist Heinz Kloss — detailed things from ethnicity and languages of cities' populations to listing Jewish organizations, and Kent further explained to The Guardian that the book is essentially proof that Hitler and the Nazi party had plans to expand the Holocaust to North America: "The Holocaust wasn't a European event, it was an event that didn't have the opportunity to spread out of Europe," he said.